133 ff., preceded by two original paper flyleaves, with first flyleaf detached and presenting an inscription with capital letters “H. V. V. 5…” (?) (perhaps an early owner’s initials or a library shelf-mark, see Wittock, 1998, p. 107, n. 14 who records similar letters and numbers in books having belonged to Giacomo Boncompagni), complete (collation i-xvi4, xvii5 [6-1, with last folio of quire cancelled], xviii4, xix4, xx3 [4-1, with last folio of quire cancelled], xxi-xxvi8, xxvii6 [8-2, with last two folios cancelled]), on parchment (ff. 1-79) and paper (ff. 80-131) (watermark presents close match with Picard 1030, Lucca, date: 1617 [although the initials are not the same]; Picard, 1013, Lucca, date: 1628 offers another match, with the papermakers initials AO but this time without the crown), written in two different calligraphic scripts, for the most part in a fine cancellaresca formata (ff. 1-64; 68-75v; 77-131) and the rest in an elegant Roman script (ff. 65-67v; 75v-76v), in brown ink, ruled in plummet (justification 150 x 100 mm.), with rubrics and headings in Roman script, rubrics in red, title in gold in figurative frontispiece, ornamental initials in dark brown to black ink, 6 large figurative initials drawn in brown ink (of which one is historiated) [see Decoration below]. Modern limp vellum, smooth spine, edges gilt, boards from original binding preserved, manuscript and original boards placed in a modern folding cloth box. Boards present remnants of original Roman (?) binding made for Francesco Boncompagni, gold-tooled limp vellum over pasteboard, gilt filet borders with gilt fleurons at inner angles of frame, Boncompagni armorial stamp with demi-dragon at centre topped with a cardinal’s hat, traces of silk fore-edge ties. Dimensions 195 x 150 mm.

With fine calligraphy and expert decoration, this manuscript was apparently made for Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II and his second spouse Eleonora Gonzaga of Mantua, perhaps commissioned for them by the Cardinal Francesco Boncompagni, a famous collector and patron of arts (whose binding is preserved). Both Emperor and Cardinal had strong Jesuit ties, and the manuscript—in line with the spirituality of Ignatius of Loyola—in unpublished.

Provenance

1. Watermarks, script and decoration suggest an Italian origin for this manuscript. Watermarks are found in paper made in Lucca, suggesting that the present manuscript was copied in Italy, perhaps in the region of the Duchy of Lucca (Tuscany). The manuscript contains a Prayer dedicated to the Emperor Ferdinand II (1619-1637) or his spouse (Oratio ad…Ferdinandi Caesaris… (f. 129v)). We say Ferdinand II rather than Ferdinand III (who succeeds to his father in 1637) largely because of the dates suggested by the watermarks. Ferdinand is referred to as “Caesar” that is “Emperor,” the title that he received when elected in 1619. Also, with reference to his spouse, Ferdinand II married twice, once in 1600 with Maria Anna of Bavaria (1574-1616) and a second time with the Italian Eleonora Gonzaga of Mantua (1598-1655), in 1622. Could the present manuscript have been commissioned on the occasion of his wedding to the Italian Eleonora Gonzaga, thus some time shortly after 1622? Finally, if this manuscript was indeed commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Boncompagni, it was done so when he was Cardinal, a title which he earned in 1621: the binding bears his arms surmounted by his Cardinal’s hat. Thus it seems possible the manuscript was copied certainly after 1619 (when Ferdinand takes on the title of “Caesar”), before 1637 (when Ferdinand II is replaced by Ferdinand III), shortly after or around 1622 (the date of his second marriage to Eleonora Gonzaga, as his first wife dies before he is made “Caesar”).

2. Contemporary or near-contemporary binding made for Cardinal Francesco Boncompagni (born in Rome 1596-died in Naples in 1641), proof that the manuscript was either commissioned by the Cardinal or owned very early on. Although the present manuscript has been since rebound, the boards of the original binding have been preserved. These boards contain precious heraldic testimony of the first or early owner of the present manuscript (perhaps even its original patron?). The gilt arms placed in the center of the original boards are those of Cardinal Francesco Boncompagni, made Cardinal in 1621. The binding was thus executed after 1621. Francesco Boncompagni was the son of Giacomo Boncompagni (1548-1612), Duke of Sora, powerful feudatory and patron of arts and culture, natural son of Ugo Boncompagni, future Pope Gregory XIII. Son of Giacomo and Costanza Sforza, Francesco Boncompagni was much appreciated by Pope Gregory XV, who helped him obtain his cardinalate. Francesco Boncompagni would later become archbishop of Naples in 1626. He died in Naples in 1644, leaving an important collection of Greek and Latin manuscripts to the Biblioteca Vaticana, as well as an important number of printed books to the Collegio Germanico di Roma, a major center for Jesuit learning (see Coldagelli, DBI, XI, pp. 688-689). His father Giacomo Boncompagni was an important bibliophile, see Wittock (1998). Ugo Boncompani, Pope Gregory XIII, had also given a number of books to the Collegio Romanico: see “Falcone L. Incunabole e cinquecentine della biblioteca di Gregorio XIII Boncompagni dal Collegio Germanico alla Pontificia Universita Lateranense, Vatican, 1998). According to G. M. Mazzuchelli, Gli Scrittori d’Italia, Francesco Boncompagni was the author of a number of works, including sermons, all unpublished (Mazzuchelli, 1763, II, 4, p. 2370).

Text

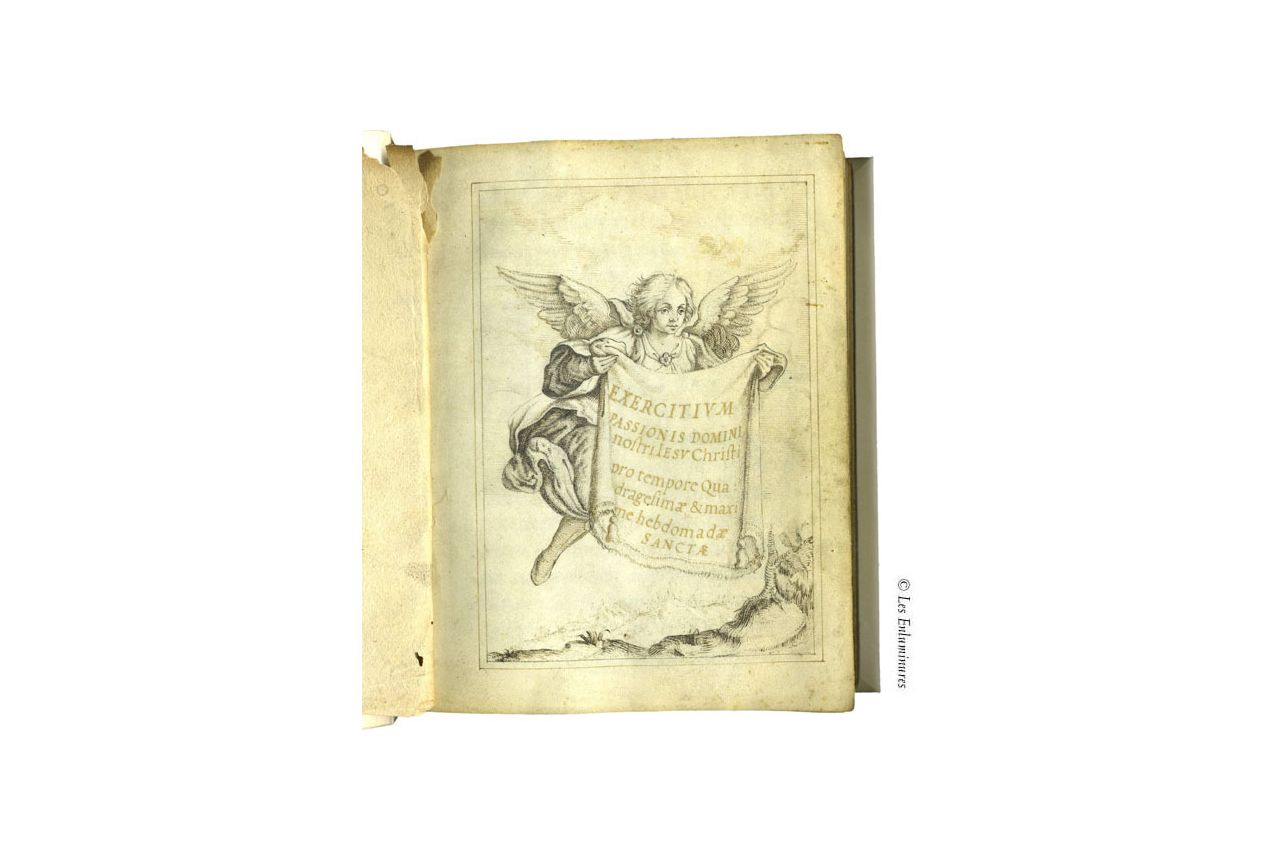

f. 1, Title-page, Exercitium passionis domini nostri Iesu Christi pro tempore quadragesimae et maxime hebdomadae sanctae;

f. 1v, blank;

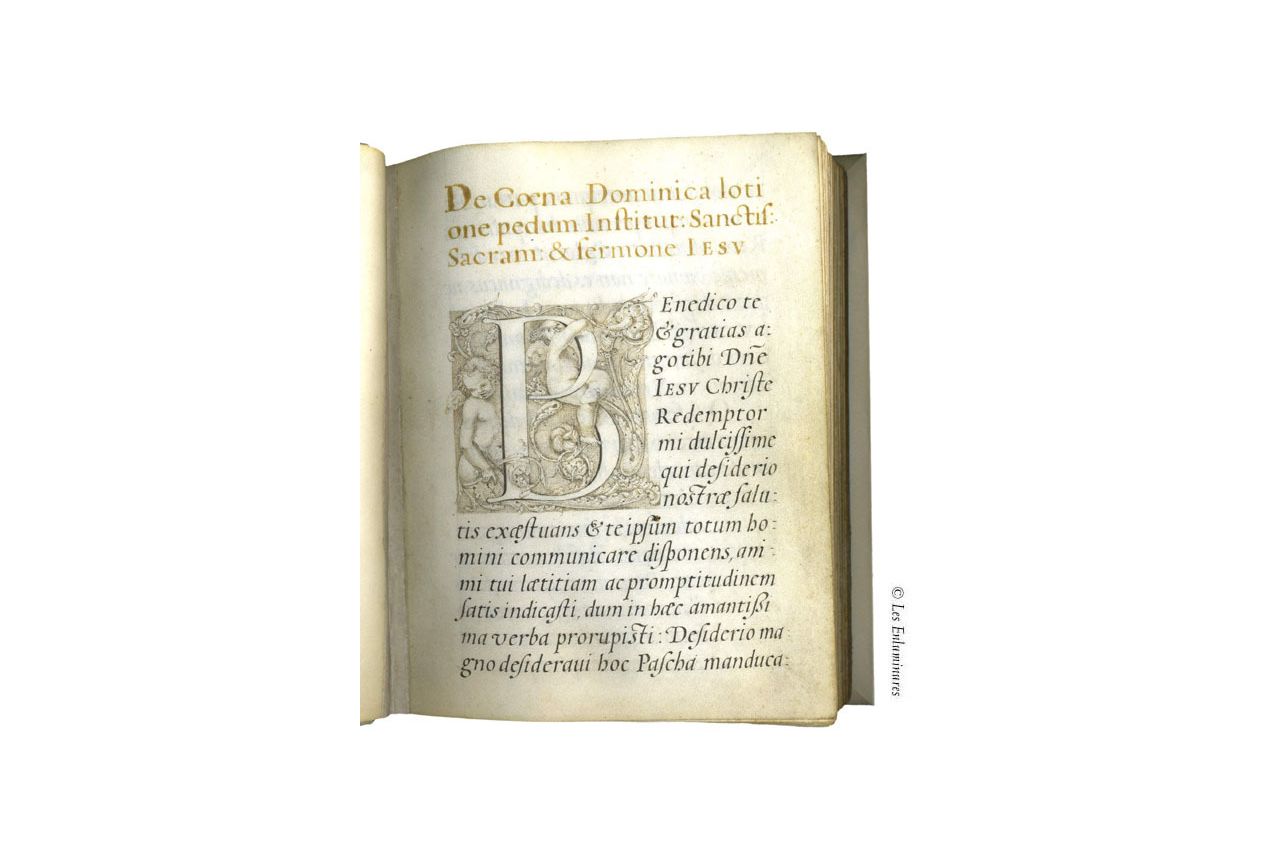

ff. 2-64, Exercitium passionis domini nostri Iesu Christi pro tempore quadragesimae et maxime hebdomadae sanctae [Spiritual Exercise on the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ during Lent (Quadragesima) and the Holy Week], in gold, “De coena dominica lotione pedum institutione sanctissime sacramente et sermone Iesu”; incipit, “Benedico te et gratias ago tibi domine iesu christe redemptor…”; followed by: “De venditione et traditione iesu per iudam proditorem”; “De ingressu domini iesu in hortum oliveti et mysteriis ibidem factis”; “De captione et deductione iesu poenisque et contumeliis apud annam et caypham perpessis”; “De presentatione iesu ante pilatum et herodem”; “De flagellatione domini iesu ad columnam”; “De christi coronatione et illusione”; “De christi productione ad populum ecce homo”; “De christi domini nostri baiulatione crucis”; “De crucifixione iesu”; “De perforatione manuum et pedum christi in crucifixione”; “De elevatione crucis”; “De septem verbis in cruce prolatis”; “De expiratione et transfixione iesu”; “De depositione iesu de cruce et sepulture”; “Oratio de vulneribus christi eiusque siti in cruce”;

f. 64v, blank;

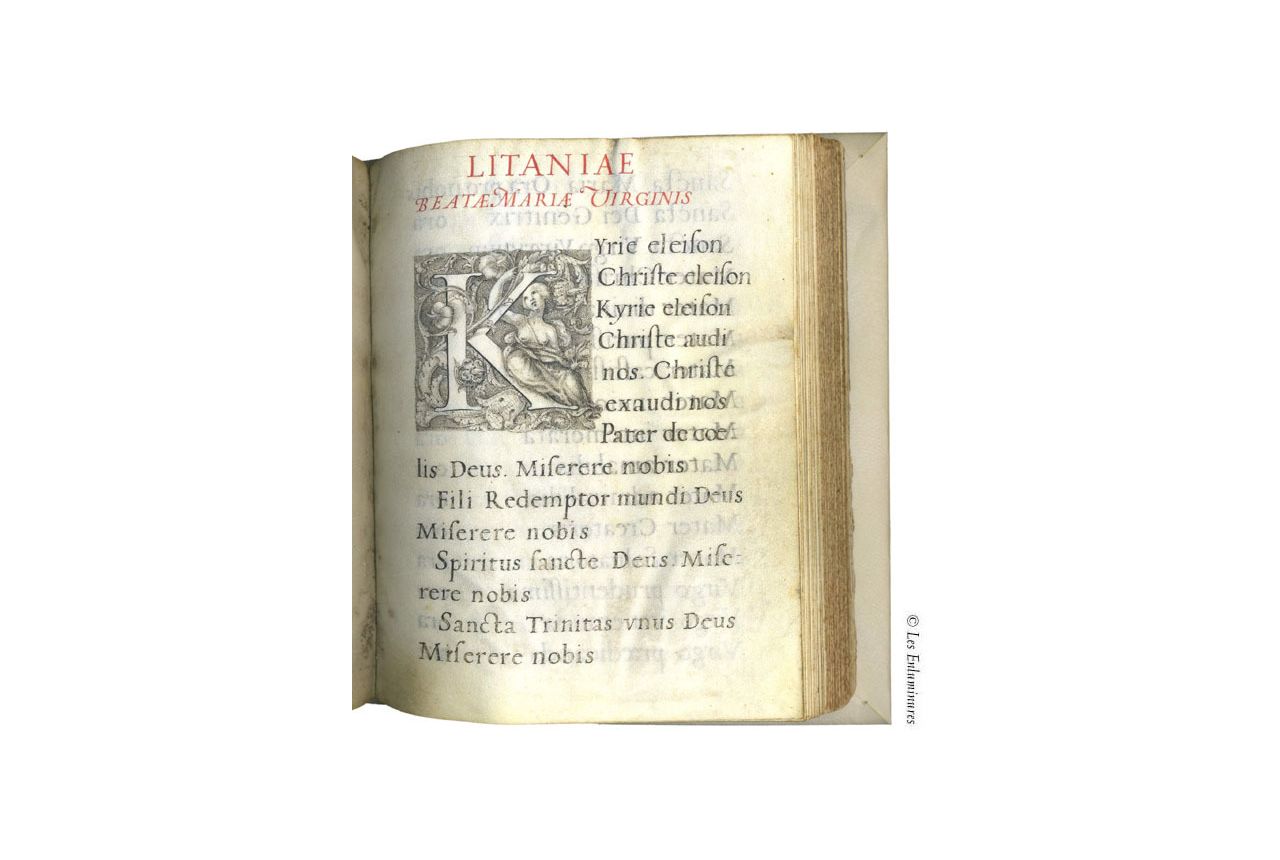

ff. 65-67v, Litany for the Virgin; Litaniae beatae mariae virginis; incipit, “Kyrie eleison Christe eleison Christe audi nos…”;

ff. 68-76, Hymn of Saint Casimir, rubric, Hymnus sancti casimiri; incipit, “Omni die dic mariae mea laudes anima…”;

This hymn was most certainly not composed by Saint Casimir (1458-1484), patron saint of Lithuania (Feast 4 March) but also widely honored in all of Central Europe, in particular in Poland. Prince of Poland, Casimir was the son of King Casimir III, and was closely tied to the governance of Poland and Lithuania. He died very young at only 23 years of age (See “Saint Casimir--4 mars”, in Vies des saints par les RR. Bénédictains, 1941, pp. 80-83). The presence of this hymn is interesting and confirms the Central European connection. Authorship of the Hymn itself was attributed to Saint Casimir by U. Chevalier, Repertorium hymnologicum…(1892-1921), t. II, p. 261, n. 14070. It has since been proven that the hymn appears in manuscripts from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

ff. 76v-79v, Prayers to protect against sudden death, to lead a good life and death, Prayers to the parts of Christ’s body, with the following rubrics, Oratio pro conservatione a subitanea et improvisa morte; Oratio ad B. Virginem pro bono fine et vitae impetrando; Salutationes ad omnia membra Christi;

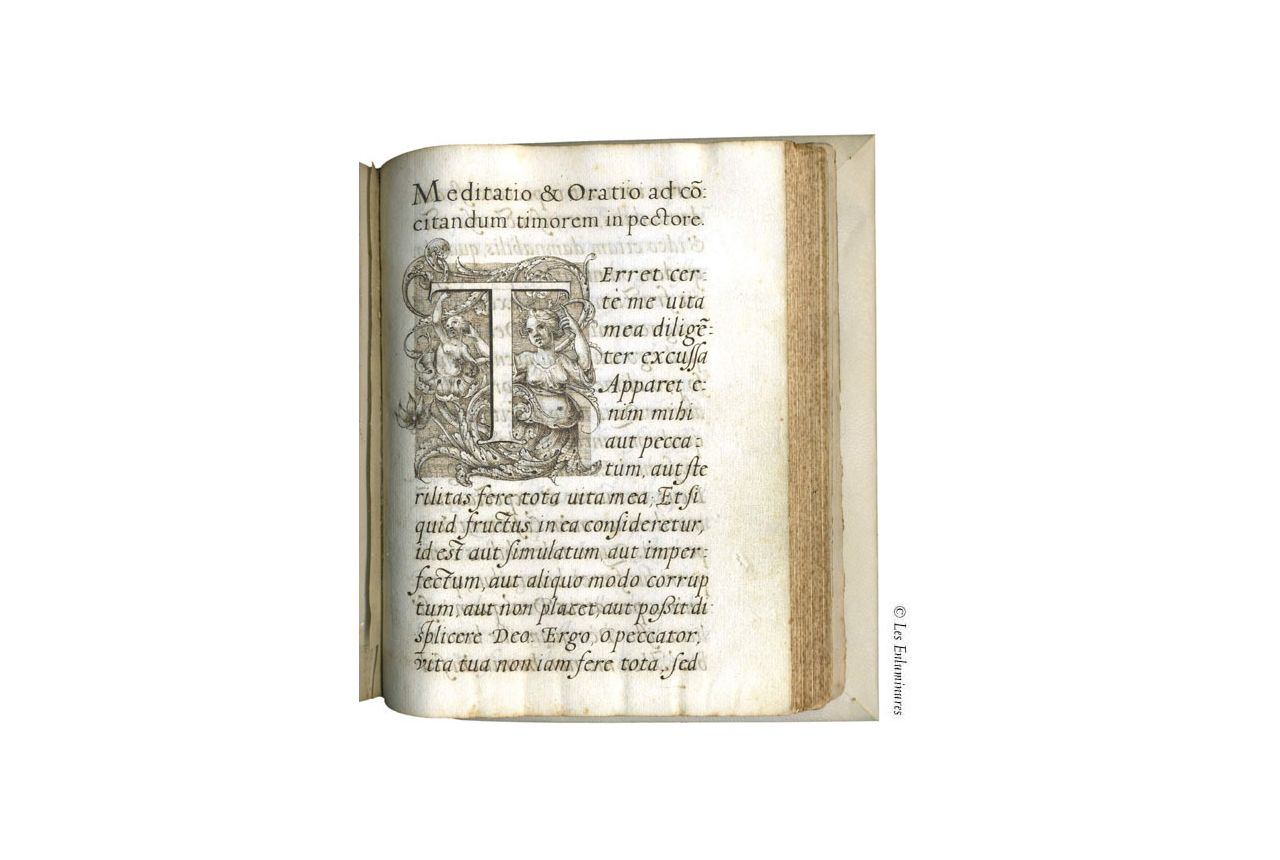

ff. 80-85v, Saint Anselm, Meditation and Prayer, heading, Meditatio et oratio ad concitandum timorem in pectore; incipit, “Terret certe me vita mea diligenter…”;

ff. 85v-102v, Prayers for the Dying, rubric, Orationes ad salutarem mortis horam impetrandem; Orationes ad extremi iudicii terrores atque inferorum cruciatus deprecandos;

ff. 102v-113v, Exercitium compunctionis [Exercise of Compunction], rubric, Oratio qua peccator agnoscens et deflens miseriam suam lumen veniam et remedium a Deo postulat;

ff. 113v-121, Prayer to obtain conversion, rubric, Oratio ad obtinendam veram conversionem et dolorem de peccatis cum recursu ad beatissimam virginem Mariam et D. Magdalenam;

ff. 121-123, Prayer for sinners, rubric, Oratio hominis in flagitium prolapsi;

ff. 123-127, Prayer to resist sins, rubric, Oratio ad peccatorum detestationem impetrandam;

f. 127v, blank;

ff. 128-129, Prayer to the Virgin Mary when Dying, rubric, Oratio ad Mariam ut in hora mortis nos suscipiat et defendat;

ff. 129-131, Prayer dedicated to the Emperor Ferdinand or his spouse, rubric, Oratio ad dominum Ferdinandi Caesaris aut serenissimae reginae nostrae; incipit, “Miserere mei Miserere mei fili dei iesu christen rex regum….”; explicit, “[…] cum omnibus electis contemplemur et glorificemus in aeterna beatitudine. Amen”;

Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor (1578-1637), married Maria Anna of Bavaria (1574-1616) on 23 April 1600. They had seven children, including the following Emperor, Ferdinand III (1608-1657). However, in 1622 Ferdinand II married a second time, the Italian Eleonora Gonzaga of Mantua (1598-1655). By that time Ferdinand II had been already been elected Emperor, succeeding Emperor Matthias in 1619. Before becoming Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Ferdinand was Archduke of Austria, King of Bohemia and King of Hungary. From 1590 to 1595 he was educated at the University of Ingolstadt by Jesuits whose aim was to make him a strict, rigidly Catholic ruler. In 1596 he took over his hereditary lands and, after a pilgrimage to Loreto and Rome, set about suppressing Protestantism by forcing the great majority of his subjects to adopt the Roman Catholic faith.

ff. 131v-133v, blank.

This codex is somewhat mysterious, but provides a few clues to its origin and purpose. Amongst a number of elegantly copied texts including a “Spiritual exercise” on the Passion of Christ, prayers and hymns, this manuscript contains a prayer dedicated to an unnamed Holy Roman Emperor and his spouse (not recorded in U. Chevalier, Repertorium…). There is a possibility–but without certainty as this is a working hypothesis–that the manuscript was made on the occasion of the Emperor’s second marriage in 1622 to the Italian Eleonora Gonzaga of Mantua and commissioned in Italy where it was copied and decorated. Bound very early on in a gilt heraldic vellum binding, the manuscript was possibly commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Boncompagni, grand-son of Pope Gregory XIII, on the occasion of his second wedding to an Italian native. His arms are found on the original covers of the manuscript. It seems unlikely the manuscript was commissioned to mark the election of Ferdinand II in 1619, as the prayer would not have been also dedicated to his spouse, as Ferdinand II was a widow in 1619 (his first wife Maria Anna of Bavaria died in 1616). He only remarried in 1622. If Boncompagni is indeed the commissioner of the manuscript (and not just a very early owner), he was made cardinal in 1621, and would not have had his Cardinal hat included in his arms before his nomination. Additional comparisons with other manuscripts commissioned by Francesco Boncompagni are necessary to shed light on the mystery of this manuscript. However it is clear the present manuscripts attests to the important ties established between Italy and Austria, both championing Catholic orthodoxy and firmly set against Protestantism. Ferdinand and his successors re-catholicized parts of Austria (including Vienna), Bohemia and Hungary. In this effort they were strongly supported by the pope and Catholic hierarchy, and this led to increased cultural links between Vienna and Italy.

Both title and content of this unpublished work bear a most decided Jesuit influence (there is no record of this work in Sommervogel or in other Jesuit bibliographies and repertories of anonymous works). The title “Exercitia” recalls that of the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola (written within 1522-1524), which consists of a brief set of meditations, prayers and mental exercises, designed to be carried out over a period of 28 to 30 days. They were written with the intention of enhancing and strengthening one's faith-experience in a manner that has distinctly Roman Catholic aspects.

In our manuscript, one notes the presence of the famous Hymn of Saint Casimir, which is decorated with a historiated initial representing the Saint, particularly venerated in Central Europe. There are traces of devotion to Saint Casimir in Jesuit circles (for example there is the Jesuit Church of Saint Casimir in Vilnius, Lithuania). Lithuanian Jesuit missions and colleges contributed considerably to the development of the cult of St. Casimir. He was chosen as an example of chastity and piety. Through Jesuit colleges and through dynastic ties of Lithuanian-Polish kings the cult of St. Casimir spread to Austria, Bavaria, Belgium, Italy, and other countries. Pope Paul V in 1621 proclaimed the cult of St. Casimir as part of the universal worship of the Catholic Church, by including it in the missal and the breviary for priests.

Both the Boncompagni family and Ferdinand II were closely tied to the Jesuit order and received Jesuit teachings. The Jesuit Collegio Romano and its influence grew substantially under the patronage of Ugo Boncompagni (Pope Gregory XIII, Ugo being Francesco’s grand-father) and the Collegio Germanico inherited Francesco Boncompagni’s collection of printed books. Emperor Ferdinand II was educated in Bavaria at the Jesuit University of Ingolstadt. The present manuscript ought to be studied in conjunction with other manuscripts and works produced in Jesuit circles, on which little work has effectively been done.

Decoration

In addition to its elegant and very regular slanted and Roman scripts, the present manuscript boasts a fine title-page: the title of the work has been inscribed in gold letters on a shroud held up by an angel, wings spread out and in suspension in the air. He is characterized by a very soft gaze.

There are also many small ornamental initials and six decorated or historiated initials, all traced in brown ink, presenting figures that evolve in swirling acanthus leaves and floral motifs. These are found on ff. 2 (Two Putti), 65 (Half-figure with bare torso), 68 (Kneeling Saint Casimir, the only historiated initial), 80 (Two half-figures, one with bare torso), 128 (Two Putti), 129v (Half-figure with bare torso).

A number of questions remain to be answered. Do the present ink drawings compare with other recorded drawings? Are they copies of woodcut or engraved typographic ornaments and figures from the Renaissance and Italian Settecento? A study of seventeenth-century Italian ornaments and decoration, of emblem-books and frontispieces should yield some fruitful comparisons. A good example of the interest of Jesuits in ornamentation and book decoration and illustration is exemplified by an interesting volume containing a compilation of examples of engraved ornaments favored by the Jesuits (see Simon Jervis, “A Seventeenth-Century Book of Engraved Ornament”, in The Burlington Magazine 128, no. 1005 (1986), pp. 893-903; Brussels, BR, Reserve, VB 5335). Settecento Italian ornaments and graphic design certainly remains a neglected area of research.

Literature

Alonzi, L. Famiglia, patrimonio e finanze nobiliari. I Boncompagni (secoli XVI-XVIII), Piero Lacaita Editore, 2004.

Disdier, M.-Th. “Boncompagni (Francesco)” and “Boncompagni (Giacomo),” in Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, Paris, 1937, tome IX, col. 820-821.

Coldagelli, U. “Boncompagni, Francesco”, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, XI, Rome, 1969, p. 688-689.

Mazzuchelli, G. M. Gli Scrittori d’Italia…, Brescia, 1763.

Picard, G. Die Wasserzeichenkartei Piccard im Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart. Findbuch. 11, Wasserzeichen Kreuz, Stuttgart, 1981.

Picard, G. Veröffentlichungen der Staatlichen Archivverwaltung Baden-Württemberg...:Die Turm-Wasserzeichen, Stuttgart, 1970.

Schmerber, C. “Exercices spirituals,” in Dictionnaire de spiritualité ascétique et mystique, Paris, Beauchesne, 1961, col. 1902-1949.

Sommervogel, C. Dictionnaire des ouvrages anonymes et pseudoanonymes publiés par des religieux de la Compagnie de Jésus, Paris, 1884.

Wittock, M. “Giacomo Boncompagni: heurs et malheurs d’une bibliothèque,” in Mélanges d’histoire de la reliure offerts à Georges Colin, Brussels, 1998, pp. 103-118.

Online Resources

On Francesco Boncompagni

http://www.fiu.edu/~mirandas/bios1621-ii.htm#Boncompagni

Francesco Boncompagni: His Portrait and Arms

http://www.araldicavaticana.com/b057.htm

On Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_II%2C_Holy_Roman_Emperor

On Saint Casimir

http://www.lcn.lt/en/bl/sventieji/kazimieras/IIM 89096 (MS 19) Jesuit Exercise on the Passion_lh.pdf