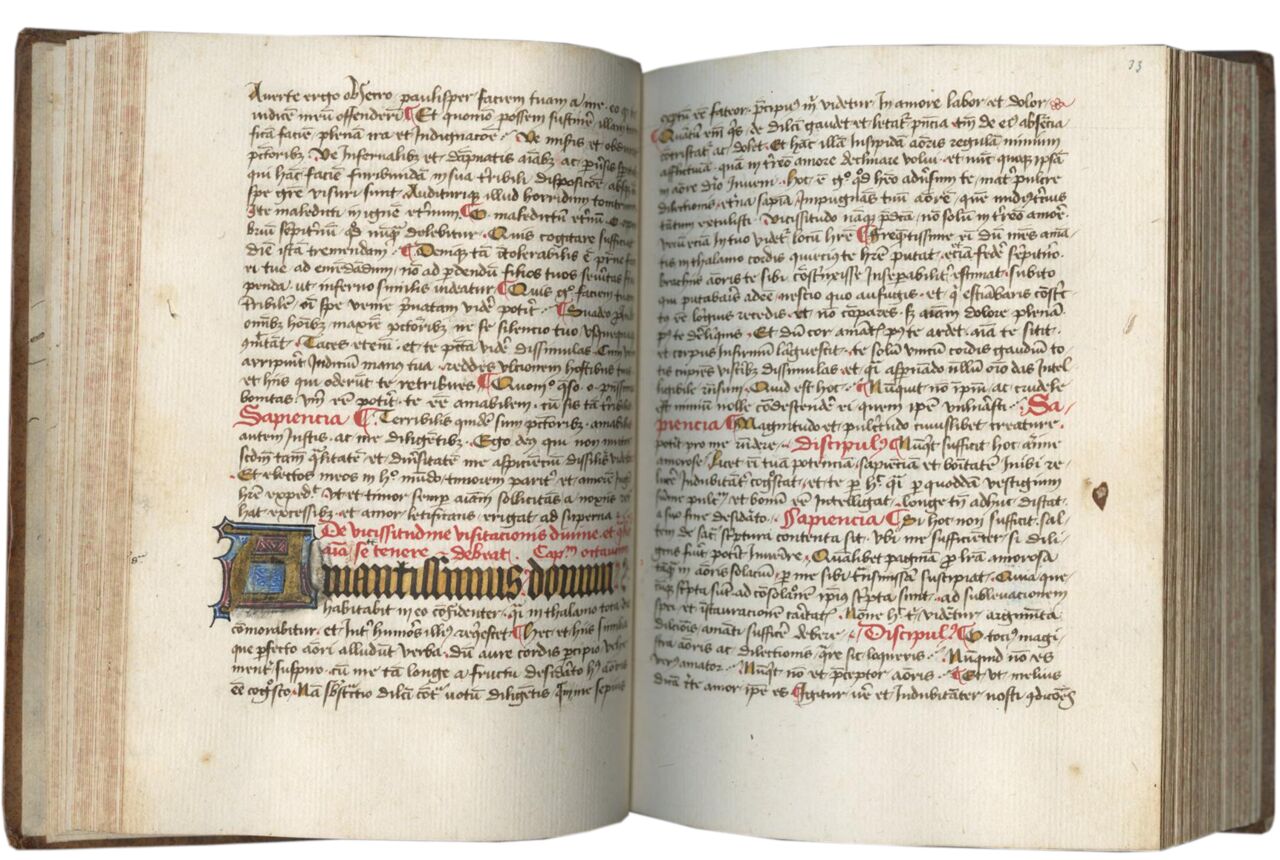

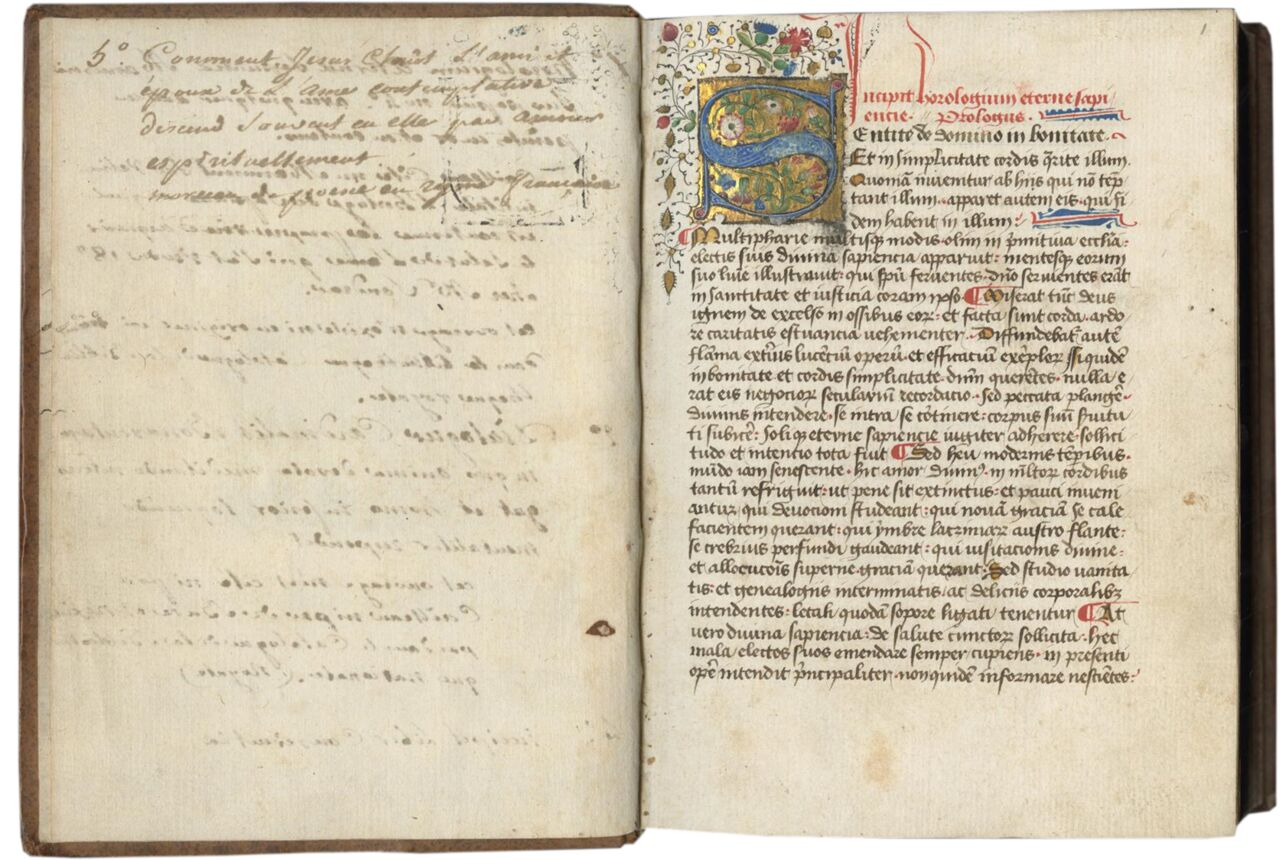

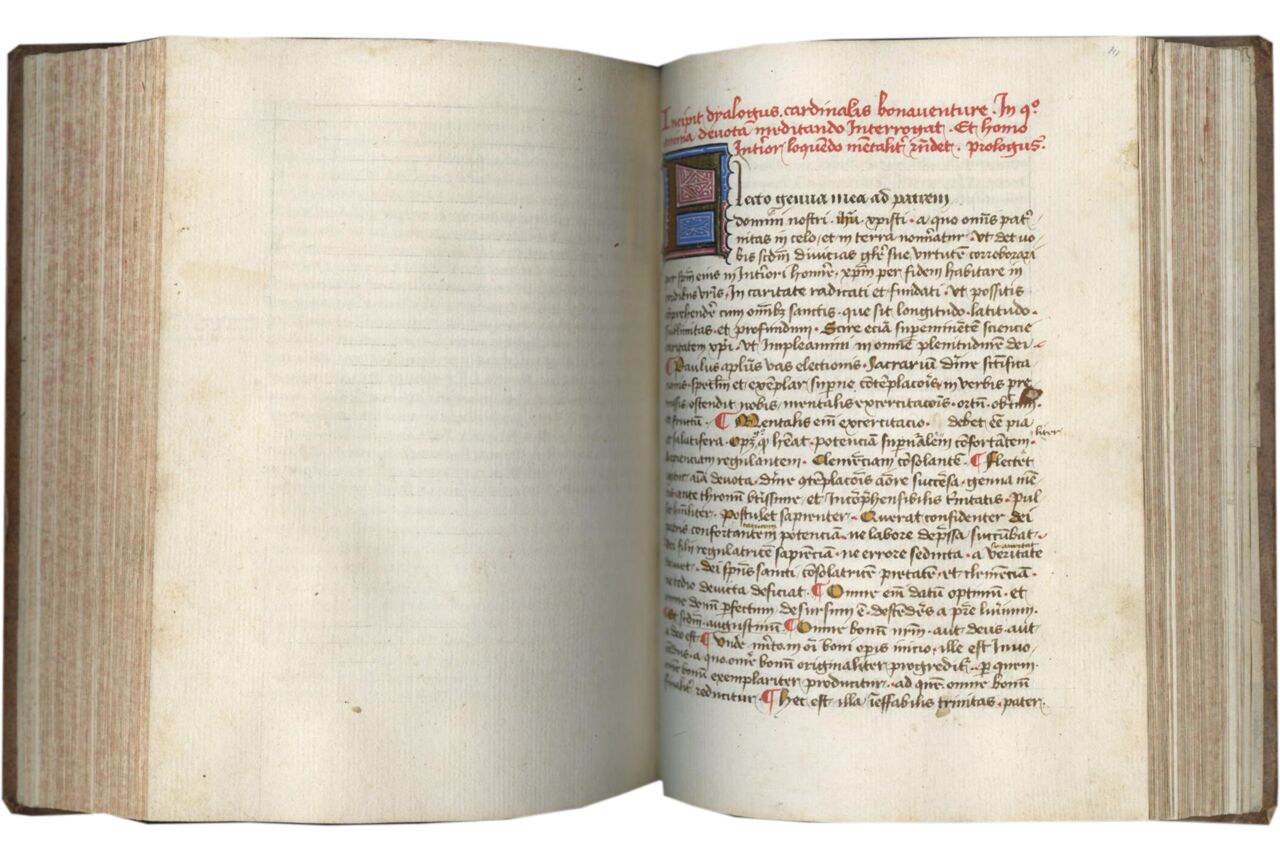

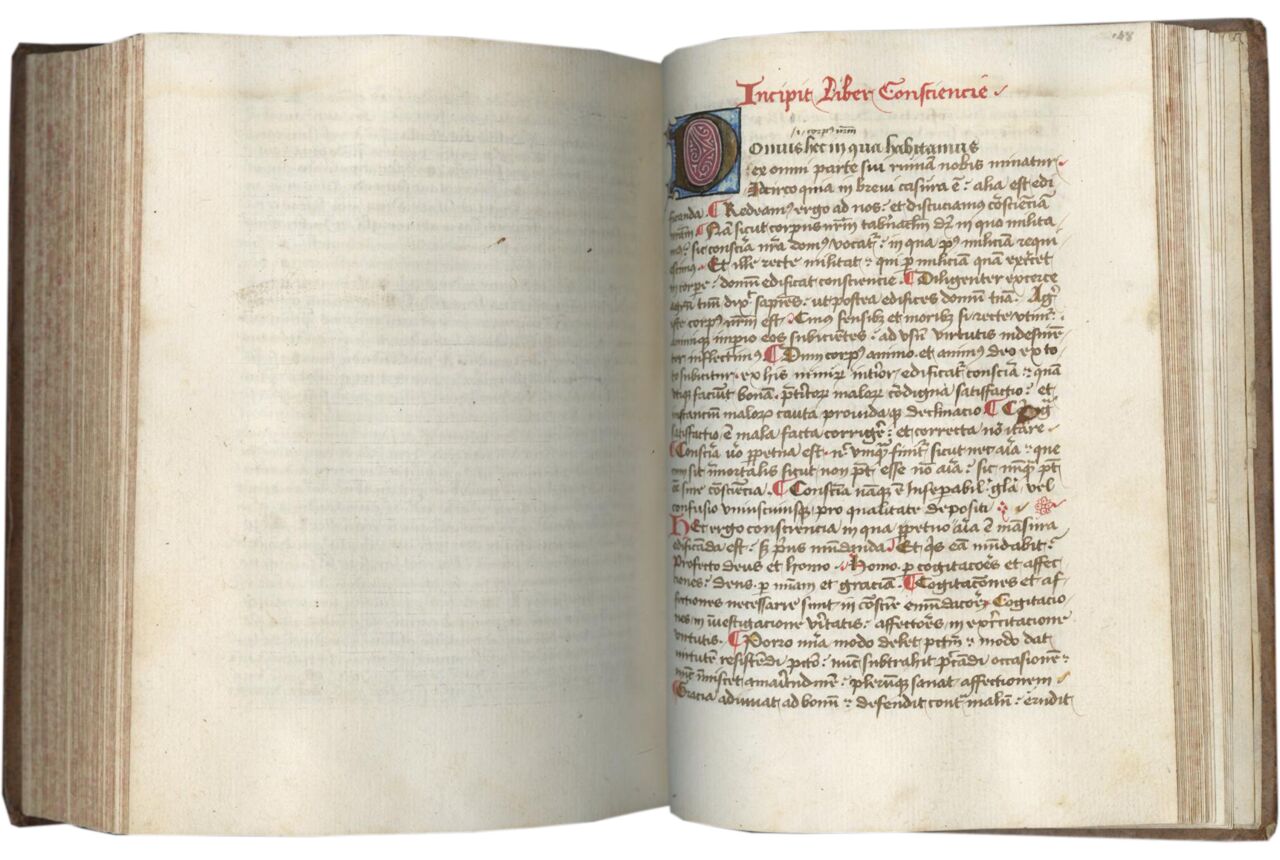

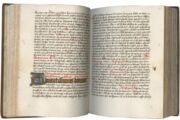

i + 169 +i folios on paper, unidentified flower, spur, and harp watermarks in gutter, modern foliation in pencil, upper outer rectos, 1-168 with errors, repeats 143 and skips to 146, complete (collation i6 ii10+1 [singleton added before f. 10] iii-ix12 x8 xi-xiv12 xv12), ruled in lead with full-length vertical bounding lines and two full-length horizontal bounding lines, one each on the top and bottom of the text block, (justification 140 x 105mm.), ff. 1-166v written in batârde script in brown ink, ff. 167-168v written in batârde script in faded black ink, all texts written in one column of between 30-34 lines, instructions in outer margins for rubricators and initial artists throughout (trimmed), rubrics in red in a Gothic bookhand, incipits written in black ink in a Gothic bookhand, paraphs marked in red ink, capital letters highlighted in yellow, red and blue line fillers, 4-line blue and gold puzzle initial with red and black penwork, multiple four- to eight-line gold initials infilled in red or blue (or red and blue) with white details on grounds of the opposite color, f. 1, 7-line illuminated ‘S’ in blue on a gold ground with flowers and a strawberry, extending into a short border in the upper and inner margins of ink tendrils with leaves, flowers and gold leaves, corrections in multiple contemporary hands throughout, some small holes from insect larvae in outer margins with no loss of text, a few initials smudged, overall in very good condition. Bound in eighteenth-century speckled calfskin, spine with five raised bands, with spine label between the first and second, “horologiv sapientiae,” and paper label at the bottom, wear to the joints, bands on the spine, and corners, sprinkled edges in red and brown. Dimensions 194 x 142 mm.

A fine collection of popular late medieval mystical texts, this manuscript offers a fascinating insight into the devotional practice of a devout fifteenth-century reader who also appreciated the finer things in life. The understatedly expensive decorations in the three main texts suggest this was a special commission, and the French poem at the end confirms that this beautiful copy was actively used, most likely by the original owner, to train their mind and soul to receive an experience of the divine.

Provenance

1. Evidence of the script and high quality of the decoration suggests the manuscript was originally copied in Northern France in the mid-fifteenth century, c. 1450-1475.

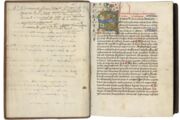

2. Bookplate of François Ferdinand pasted on inside of front cover dated 1761. Inscription, inside front cover, possibly from eighteenth century, possibly by Ferdinand. This is François Ferdinand, comte de Lannoy (b. 1732, d. Paris, 1790), from an important Belgium noble family dating back to the Middle Ages and taking its name from the town of Lannoy in northern France. The arms are those of the Lannoy family.

3. List and descriptions of contents from the nineteenth century on recto and folio of first flyleaf.

Text

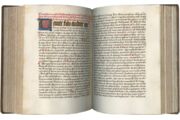

ff. 1-110, Incipit horologium eterne sapientie. Prologus, incipit, “Sentite de domino in bonitate. Et in simplicitate cordis querite illum. … Qui cum patre et spiritu sancto uiuis et regnas. Per omnia secula seculorum amen”; [f. 110v, blank];

A complete copy of Suso’s most popular work – scholars have identified over 200 surviving medieval manuscripts (Künzle, 1977) and there were ten printed editions between 1480 and 1540 – starts off the mystical training program contained in this manuscript. Structured as a dialogue between the reader (identified as the Servant) and his beloved divine Spouse (known as Eternal Wisdom), this work lays out a step-by-step procedure for creating the mindset and lifestyle necessary to establish a personal relationship with the divine.

Henricus Suso (or Heinrich Seuse) (c. 1295-1366), a Dominican friar active in southern Germany and Switzerland, was the rare mystical visionary who was also an effective teacher. One of the few theologians of his day to prefer to write and teach in German, Suso spent decades instructing non-expert audiences (especially laypeople and Dominican nuns) to understand and lead the type of inner life that could facilitate a divine experience, one of the main goals of late medieval devotion. The Horologium, originally a shorter work in German, helped bring that instruction to a more highly educated and international audience. Even in this more scholarly form, though, the work still carried Suso’s unique, and much more accessible, approach to spiritual instruction by incorporating dialogues, personal anecdotes, and literary elements from popular courtly romances.

Not surprisingly considering the number that survive, manuscripts of the Horologium are not rare, but the fine quality of this copy is noteworthy, and helps to show how Suso’s practical introduction to mystical experience found ready and willing readers among the nobility.

ff. 111-147 Incipit dyalogus cardinalis bonauenture. In quo anima deuota meditando interrogat. Et homo Interior loquendo mentaliter respondet. Prologus, incipit, “Flecto genua mea ad patrem domini nostri ihesu christi a quo omnis paternitas in celo et in terra nominantur. … Sitiat caro mea donec intrem domini dei mei. Qui est unus et trinus deus benedictus in secula seculorum amen, ihesus maria.” [f. 147v, blank];

This is a complete copy of another important work of mystical preparation. The Soliloquium was composed in 1259 or 1260, during Bonaventure’s tenure as the Minister General of the Franciscan order. Essentially a set of mental exercises to prepare the soul to effectively contemplate and comprehend the full extent of God’s love, this work was intended for “those who are less sophisticated” (simpliciores) in their theological knowledge, which fits well with the more accessible instruction in the preceding Horologium. To reach these beginners, Bonaventure also adopted the dialogue format, with the soul (anima) asking the “interior self” (homo interior) questions that invite serious reflection and meditation.

The critical edition (Opera Omnia, Quaracchi, 1882-1902, vol. 8, pp. 28- 67 and pp. xxv-xxxviii) lists 257 manuscripts of the Soliloquium that survive; see also FAMA (Online Resources), and Cardelle de Hartmann, 2007, n. R27. Few of those texts were recorded with the title it is given here. The work was first printed in Strasbourg around 1474, with 21 further editions appearing by the seventeenth century. The most recent English translation is Coughlin, 2006, beginning on p. 211.

St. Bonaventure (c. 1217-1274) was one of the most versatile religious thinkers of the thirteenth century, as he was comfortable working and teaching both systematic theology and practical devotion. It was the latter that made him most famous outside the university and his own order during and after his life, and his writings on the spiritual life became standard reading for anyone interested in developing the contemplative skills necessary to understand and, hopefully, experience divine love in the later Middle Ages. His reputation in this field was so strong that, like Bernard of Clairvaux, anonymous mystical works were attributed to him well into the sixteenth century. It would, then, make perfect sense to the late medieval owner of this manuscript to insist on his presence in their devotional collection.

ff. 148-166v, Incipit Liber Consciencie, incipit, “Domus hec in qua habitamus ex omni parte sui ruinam nobis minatur. … Quid/Unde superbit homo cuius conception culpa? Nasci poena et labor uita mori necesse quando uel ubi nescire,” Explicit [added below the line: liber conscientie hugonis de sancto victore].

A partial copy of another popular devotional text of unknown authorship that dates to the twelfth century. Most frequently attributed to Bernard of Clairvaux (as well as Hugh of St. Victor and Augustine of Hippo), the work was more commonly known as the De interori domo (On the Interior Dwelling) or De conscientia aedificanda (On Constructing a Good Conscience). Sicard identified 226 manuscript in his study of the Victorine manuscript tradition (Sicard, 2015, pp. 503-524; see also Bloomfield, 1955, no. 1787, and FAMA, Online Resources), a clear sign of its enduring reputation in devotional literature. Like its predecessors in this volume, this work also explained the nature of a “good” conscience and described particular mental exercises (such as envisioning the painful spiritual consequences of sin) that could shape and maintain it. This copy is thirteen chapters shorter than the only modern edition (which has 41 chapters); the text here ends with chapter 28 (PL 184: col. 507-538). The work was first printed under the name of Bernard of Como in Milan in 1495, with five further editions following into the sixteenth century.

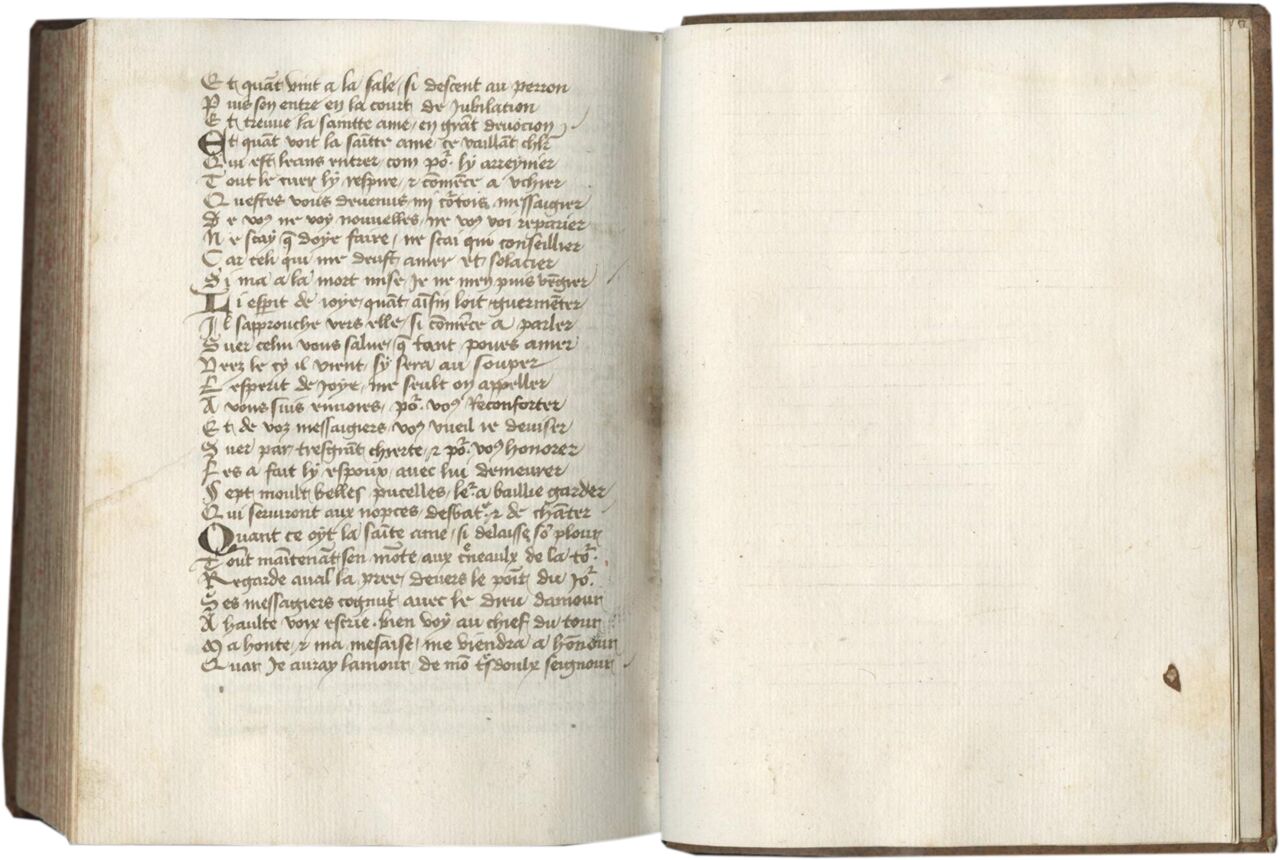

ff. 167-168v, Comment ihesus lami et espoux de lame deuote et contemplatiue descent souuent un elle par amour esprituellement, incipit, “Ceulx qui de soubtiues choses vueillent entendement/ … Ma honte et ma mesaise me viendra a honnour/ Quar Je auray lamour de mon tres doulx seignour.”

This short devotional poem in French, which may be unique to this manuscript (Jonas, Online Resources, recording only this copy), is the key to understanding the practice of a medieval owner of this volume. Written in a separate quire that was added to the preceding texts, the poem fits perfectly with the mystical and devotional character of the Latin texts, expressing the reader’s intense desire for a mystical marriage that Suso described in the Horologium. In so doing, the poem shows how a reader more comfortable with French was able to put the lessons taught by the Latin texts into practice through creating (or adding) their own texts, which fits with common practices in later medieval devotion (Fletcher, 2023).

Literature

Bloomfield, Morton W. “A Preliminary List of Incipits of Latin Works on the Virtues and Vices, Mainly of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Centuries,” Traditio 11 (1955), 259-379.

Cardelle de Hartmann. Lateinische Dialoge, 1200-1400: Literaturhistorische Studie und Repertorium, Leiden, 2007.

Colledge, Edmund, O.S.A., trans. Bl. Henry Suso: Wisdom’s Watch Upon the Hours, Washington, D.C., 1994.

Coughlin, F. Edward, O.F.M. Writings on the Spiritual Life. Works of St. Bonaventure 10, Saint Bonaventure, NY, 2006.

Cullen, Christopher M. Great Medieval Thinkers: Bonaventure, Oxford, 2006.

Fletcher, Christopher D. “The Customising Mindset in the Fifteenth Century: The Case of Newberry Inc. 1699,” in Customized Books in Early Modern Europe, 1400-1700, edited by Walter Melion and Christopher D. Fletcher, Leiden, 2023, pp. 41-64.

Künzle, Pius, ed. Heinrich Seuses Horologium Sapientiae. Erste kritische Ausgabe unter Benützung der Vorarbeiten von Dominikus Planzer, O.P., Fribourg1977.

McGinn, Bernard. The Harvest of Mysticism in Late Medieval Germany (1300-1500), New York, 2005.

Sicard, Patrice. Iter Victorinum. La tradition manuscrite des œuvres de Hugues et de Richard de Saint-Victor, Turnhout, 2015, pp. 503-524.

Van Engen, John. Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life: The Devotio Moderna and the World of the Late Middle Ages, Philadelphia, 2008.

Wijsman, H. “Patterns in Patronage: Distinction and Imitation in the Patronage of Painted Art by Burgundian Courtiers in the Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Centuries,” in S.J. Gunn and A. Janse, eds., The Court as a Stage: England and the Low Countries in the Later Middle Ages, Woodbridge, 2006, pp. 53-69.

Online Resources

FAMA, Liber de bono conscientiae

https://fama.irht.cnrs.fr/oeuvre/268834

Heinricus Suso. Horologium aeternae sapientiae, Cologne, 1480

https://portail.biblissima.fr/en/ark:/43093/edata9858d593e8fc9b916830defe2bab921c5ebffbf2

Jonas Database (section romane)- IRHT/CNRS

https://jonas.irht.cnrs.fr/consulter/oeuvre/detail_oeuvre.php?oeuvre=29104

McMahon, Arthur, “Blessed Henry Suso,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 7, New York, 1910. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07238c.htm.

Robinson, Paschal, “St. Bonaventure,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 2, New York, 1907. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02648c.htm

TM 1365