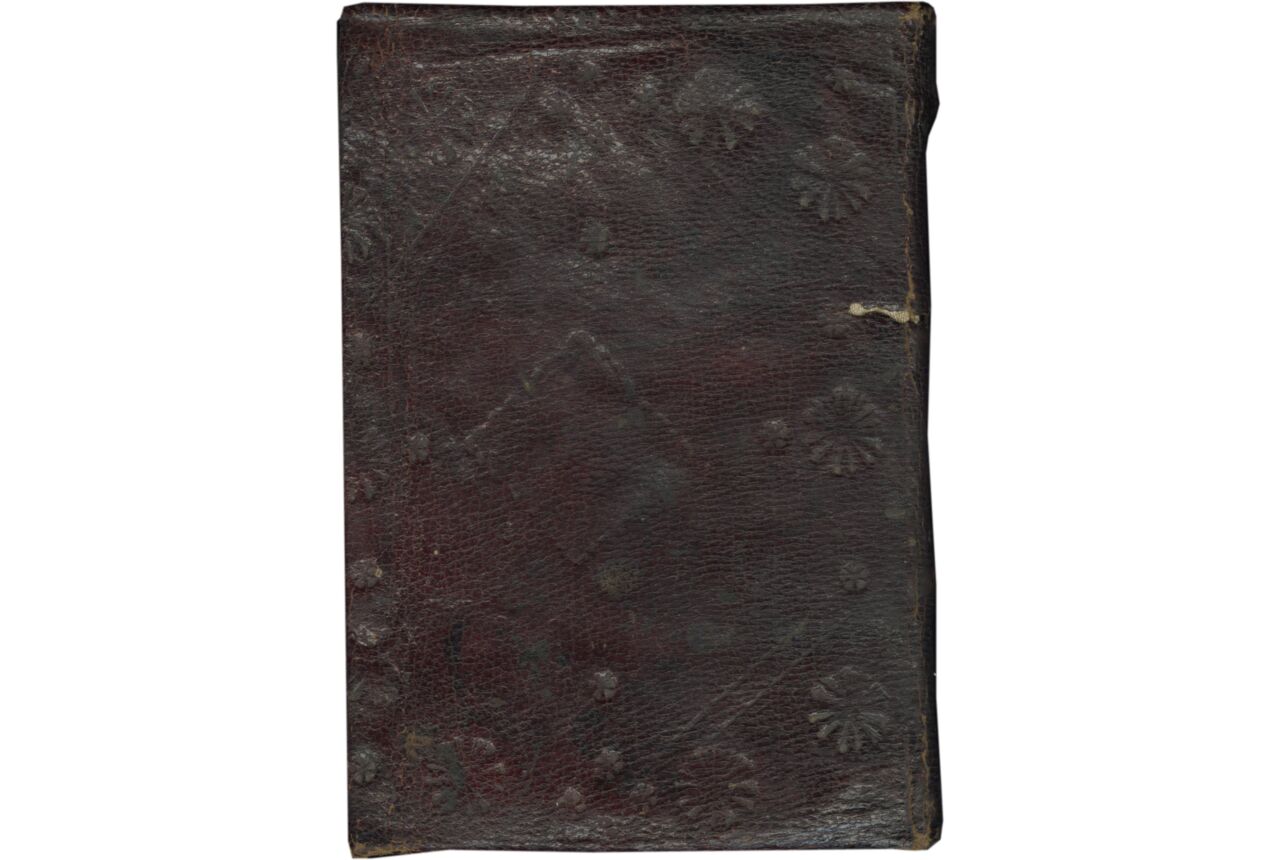

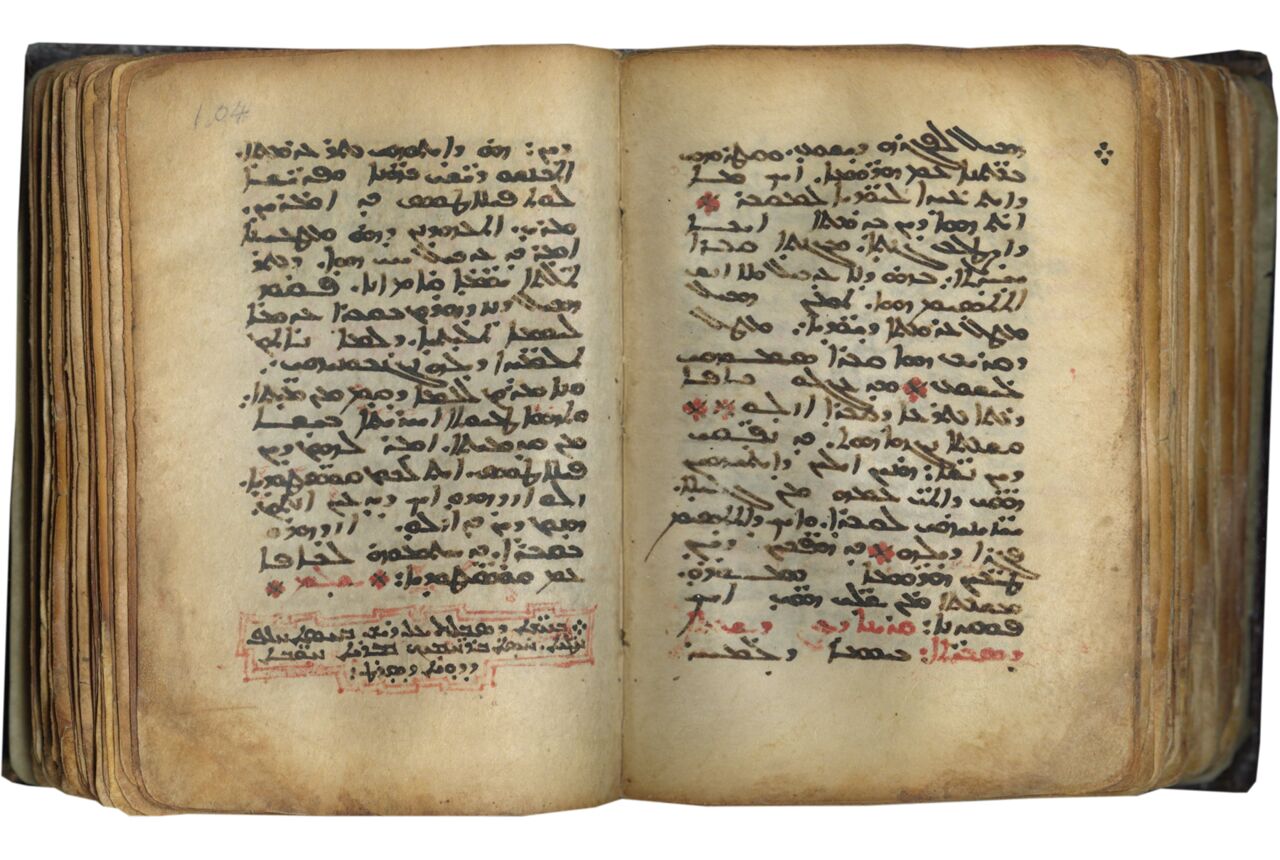

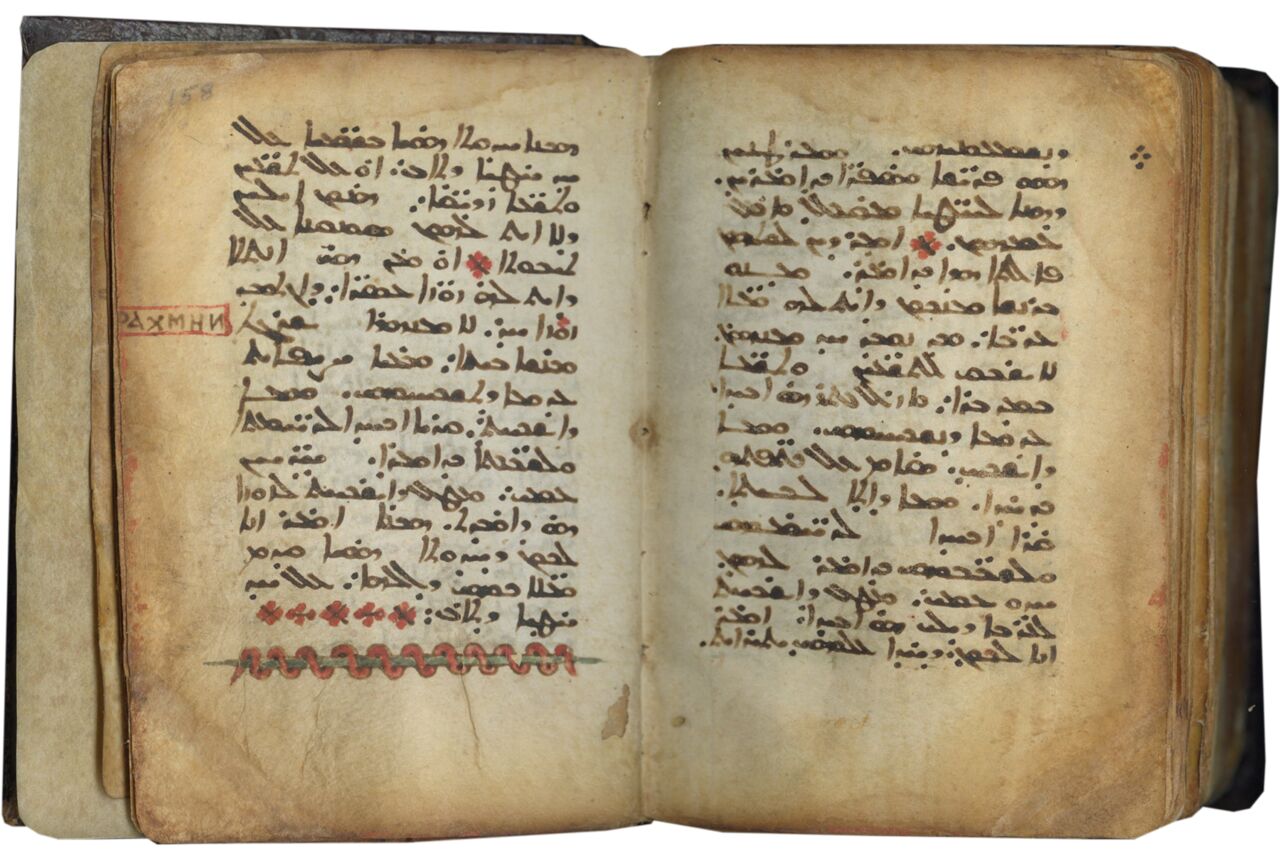

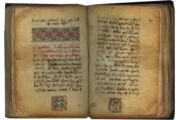

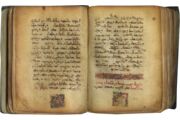

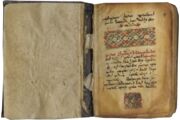

i + 165 + i folios on parchment (uneven in quality with original flaws), foliated in pencil top outer corner recto, with f. 140 erroneously foliated twice, and bound out of order with quire 16 (ff. 47-56) properly belonging after f. 164 and f. 154, belonging after f. 134, mostly in quires of 10, quires numbered on their first and last folios beginning on ff. 9v-10, incomplete at the end, missing one folio between ff. 154v-155, ff. 1-8 with the Index of Lections added shortly after the main text had been copied and now missing 2 folios (one between ff. 2-3 with lections 19-30 and one between ff. 3-4 with lections 43-54), unruled, written in a single column on 16-20 lines, in dark brown ink, rubrics in red, text in Serto script (justification 82 x 53 mm.), headers in Estrangelo script in red reading “Book of Lections for the cycle of the entire year” (ktobo d-purosh qeryone/ d-ḥudro d-kuloh shatto) in the upper margins on the last verso of a quire and the first recto of the succeeding one on ff. 1v-2, 27v-28, 36v-39, 46v, 57, 65v-74, 75v-86, 96v [no headers after f. 97, beginning of quire 9], occasional marginal inscriptions in Greek letters with names of the underlying Greek Gospel, 15 illuminated indices (ff. 1v-8v), 39 illuminated horizontal headings, and 30 illuminated medallions with catchword numbers, generally in very good condition, folios apparently untrimmed, slight browning at edges. Bound in an early, but not original, perhaps 16th century tooled brown leather binding with rosettes arranged in frame as a border on the front and rear covers, spine intact, sewn on four bands. Dimensions 117 x 80 mm.

Rare early Syriac Gospel Lectionary in the literal Syriac language translation of the Greek Gospels completed by Bishop Thomas of Harqel in 616 CE. Beautifully written partly in the classic Syriac script known as Estrangelo and mostly in its simplified cursive form known as Serto, the diminutive manuscript was presumably intended for private devotion. This distinguishes it from most other folio-sized Syriac Lectionaries designed for formal use in the liturgy. Richly illuminated indices, headpieces, and quire numbers decorate the volume throughout. Exceptional, and of considerable importance, is its lengthy colophon full of historical details, identifying the scribe and his origins, fixing the date and circumstances of transcription, and locating the place, an important monastery and pilgrimage site partially under the patronage of Queen Melisende in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Provenance

1. Signed and dated by the scribe, who gives his name as the Priest Yeshu ‘ son of Abd al-Masiḥ of Edessa in the Monastery of Simeon the Pharisee and Mary Magdalene in Jerusalem on the Seleucid Era of 1455 [= 1143-44 AD]. His colophon begins on f. 53: “To the honor and glory of the holy consubstantial Trinity, and for the splendor, adornment, and exaltation of the holy Church of God, for the preservation, good name, as well as for spiritual meditation, for the remembrance and forgiveness of his natural [lit. bodily] and spiritual fathers, the priest Yeshu ‘ son of Abd al-Masiḥ of Edessa carefully strove to copy this festival lectionary of the Gospel. [This was] when he was being educated in discipleship and subordination and rejuvenation with his uncle Ioannes, Elder and honored deacon, clothed in wool, before the feet that proclaim [cf. Isaiah 52:7] peace and welfare of our father preserved in life Moran Ignatius, holy metropolitan of the holy city Jerusalem and the coast. This book took its completion in the year one thousand 455 of the Greeks, which is according to the numbering of Alexander son of Philip the Macedonian, in the holy dwelling of Mar Shem ‘un the Pharisee and of Mary Magdalene, in the days of the reverend head priests and leaders of the Church, Mor Athanasius, patriarch of the apostolic throne of Antioch of Syria, and Mor Gabriel of Egypt, and our reverend metropolitan Ma Athanasius, mentioned earlier, the third [sc. with that name]. We beg and supplicate our Lord that He set him at our head over a length of years and grant him a good reward in His Kingdom in view of his upbringing and care for us; may peace and welfare reign in his days – or rather, all the days the world exists – in this holy monastery of Jerusalem, which has been for us a mother, and where we have been brought up and illuminated. May the Lord make the priests in it glorious; may the Lord enlighten the deacons; may the Lord support the Elder there; may God accept the labour of all the brethren who toil in it for its upkeep….” Another brief colophon on f. 55v following the Doxology, stating a “Basil [b’syl] the Deacon wrote [this].”

The Monastery of Simeon the Pharisee and Mary Magdalene is attested as being in Syrian Orthodox hands in a number of manuscripts; it was converted into a Muslim school in 1187 not long after this manuscript was copied (Palmer, 1991, pp. 28-30). The manuscript was copied in the year that Edessa fell to the Seljuks, and so perhaps, anticipating the worst, the scribe had been sent from Edessa to the safety of Jerusalem where his uncle acted as his guardian and tutor. For two detailed colophons written in Jerusalem slightly earlier (1138), see Palmer, 1992, pp. 74-94.

2. Aleppo, Syria, Collection of Malke Assad (1896-1994).

3. Assad Family, France, since 1969, then London, since 1970, Collection of the son of Malke, Elias Malke Assad, published Assam, 2015, no. 6, pp. 26-7.

Text

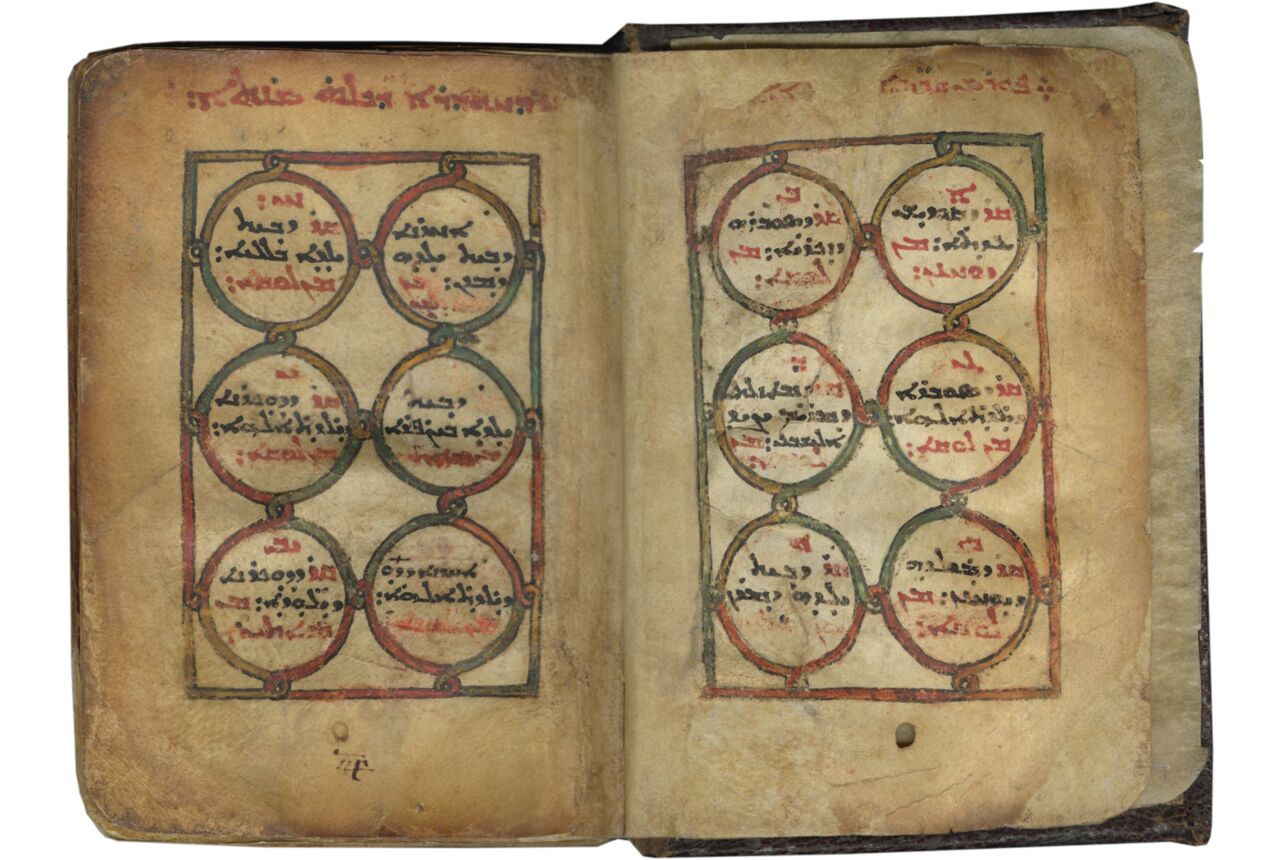

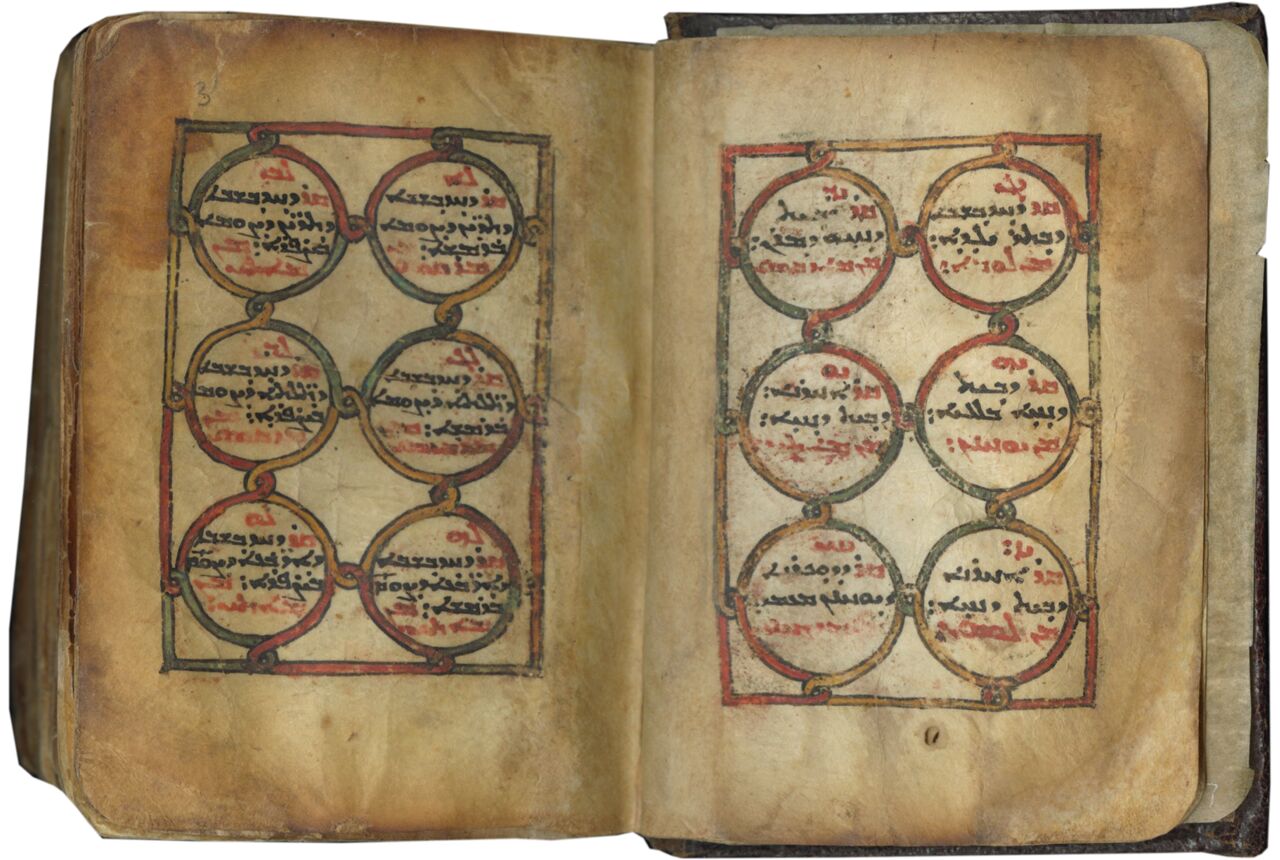

[f. 1, originally blank, with an added round stamp (red) and later owner’s signature]; ff. 1v-8v, added index of lessons numbered 1-114, with six to a page, for the whole year, now missing two leaves (see below); [f. 9, originally blank, prayer added by a later hand];

ff. 9v-10, Lection of the Consecration of the Church;

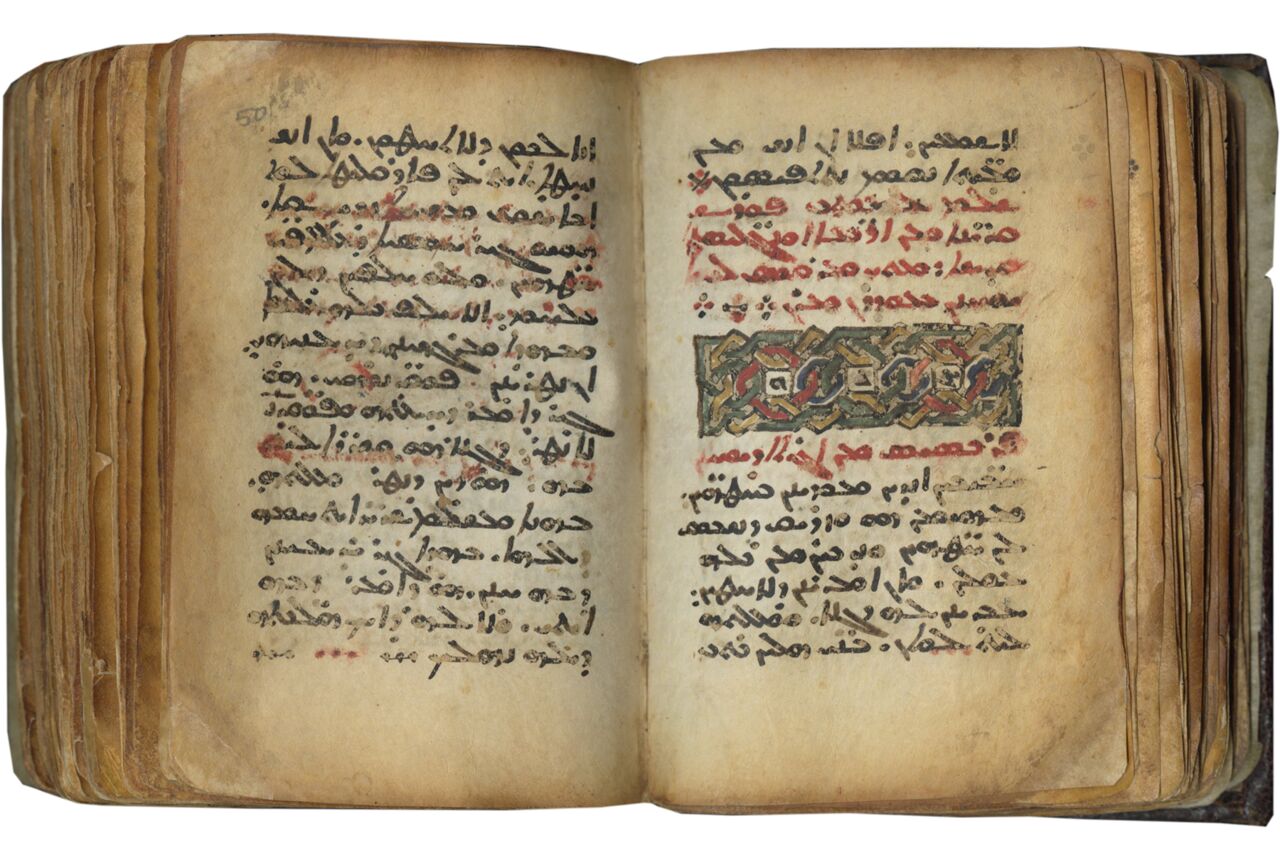

ff. 10v-164, “We commence writing the arrangement of the lections of the holy Gospels according to the edition and corrections of Thomas of Harquel,” from the Annunciation of Zacharias (f. 11) to the Commemoration of the Departed (f. 164v); [ff. 47-56, misbound, text continues from f. 164v], f. 49v, “Completed is the writing down of the separate lections from the four holy Evangelists, Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John, with the assistance of our Lord”; ff. 50v-52, Readings from the Epistles of the Apostles John, Peter, and Paul; ff. 53-55v, Colophon (see Provenance, above); f. 55v, Doxology, followed by a second Colophon; f. 56, Commemoration of Mary Magdalene, ending imperfectly.

Illustration

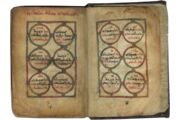

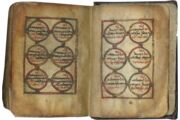

ff. 1v-8v, Index of lessons written in circles and joined together in a chain form; each circle specifies the gospel readings for the feasts of the year, painted in yellow, gold, and green;

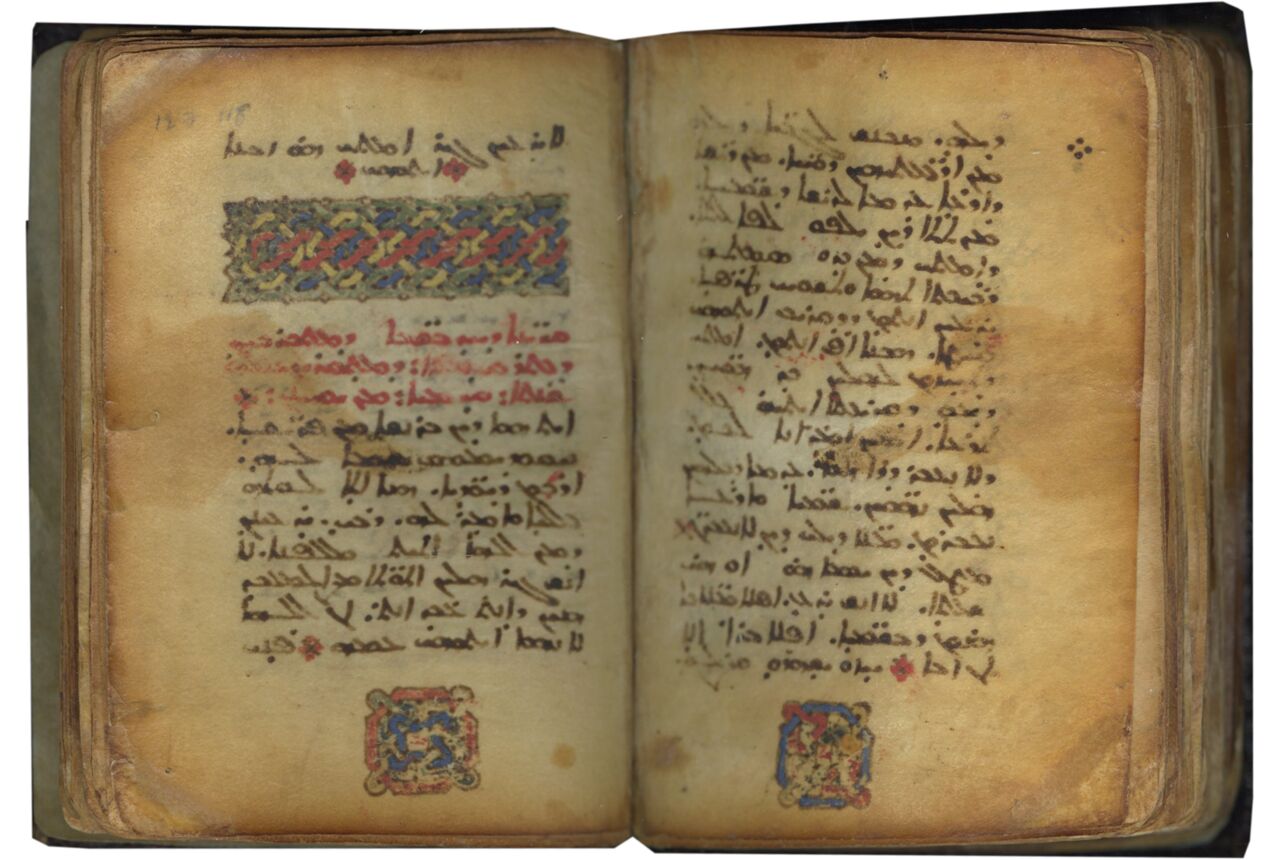

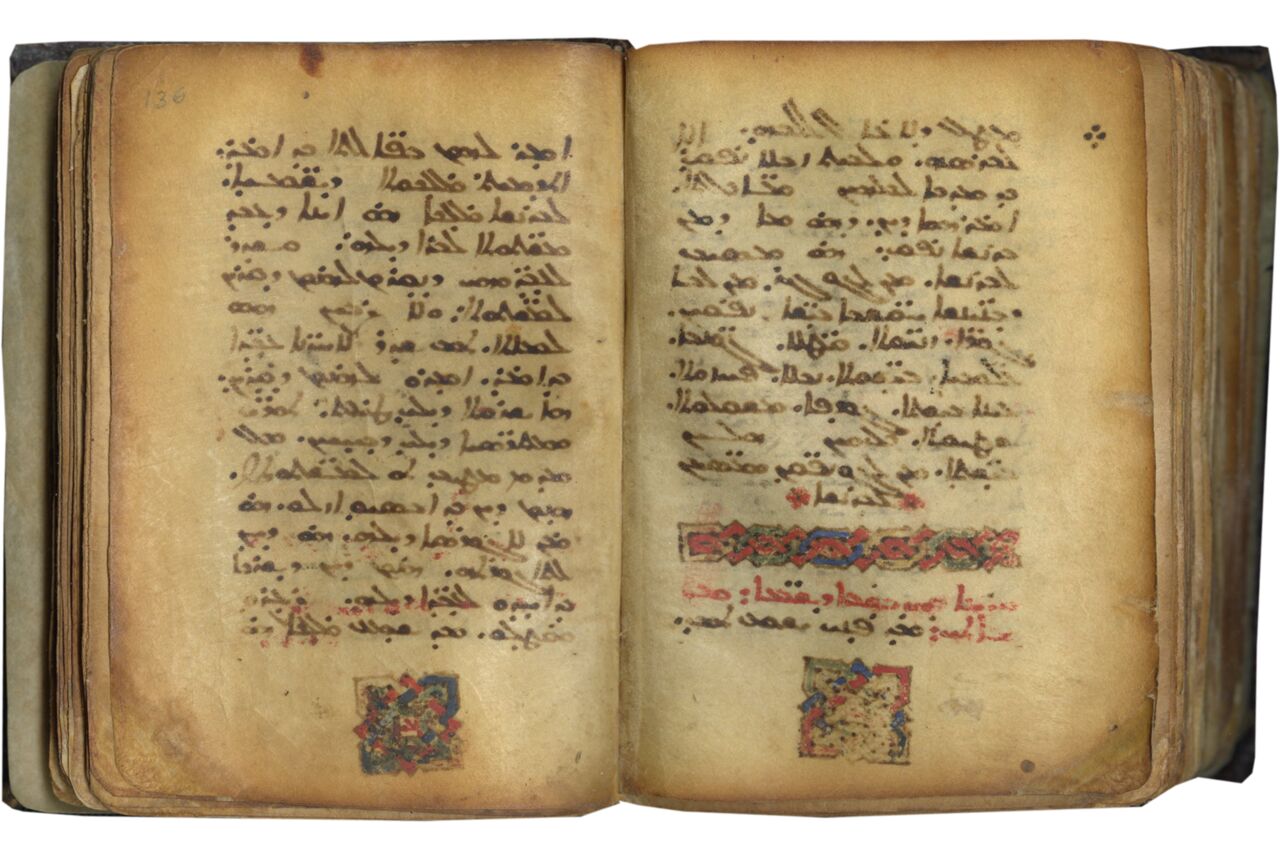

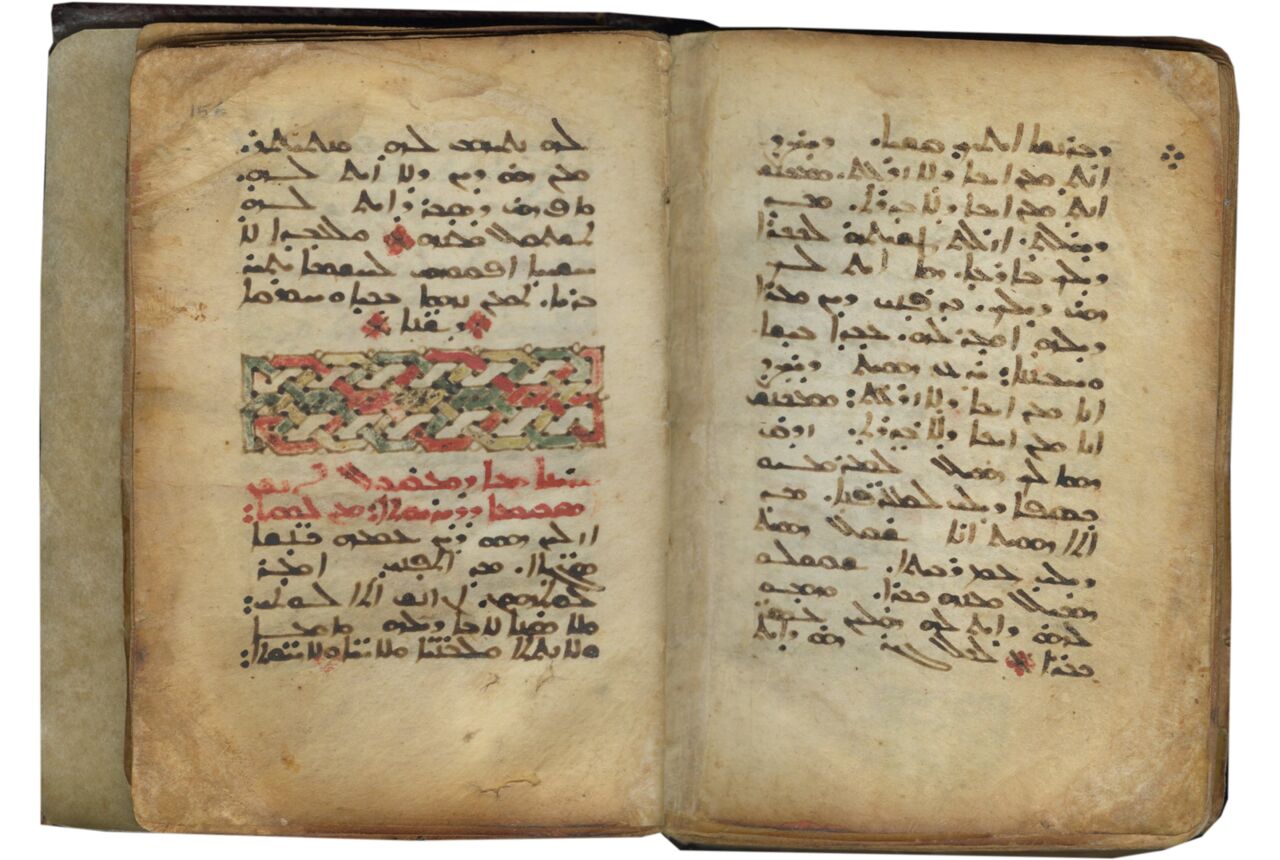

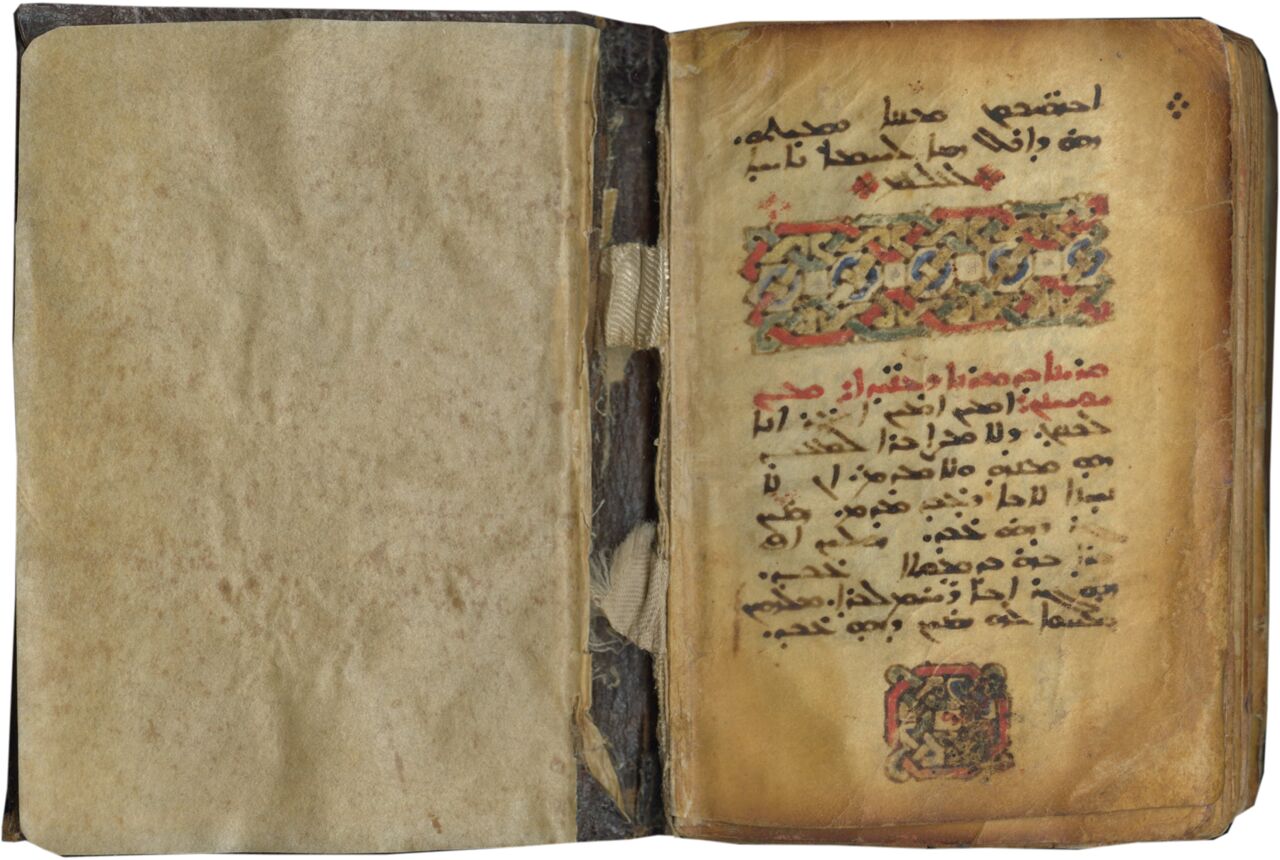

39 illuminated headings composed of horizontal bands, adorning the beginnings of lections for major feasts, some small, others large for the major feasts, all differing from one another in their intricacy and design, which demonstrate the skill of the illuminator (ff. 18, 20v, 24v, 25v, 27, 49v, 52, 53, 55v, 65v, 72, 75, 102v, 104v, 110, 112, 113v, 114v, 116, 119v, 122, 127, 129, 130v, 131v, 133, 134v, 135v, 137, 139v, 140v, 141v, 143v, 149, 150v, 142v, 146, 158, 160v);

30 illuminated quire numbers in blue, green, and yellow patterns of interlace, differing in intricacy and design, but composed primarily of geometric roundels or squares of varying forms (ff. 17v, 18, 27v, 28, 26v, 37, 46v, 47, 56v, 57, 65v, 66, 75v, 76, 85v, 86, 96v, 97, 116v, 107, 116v, 117, 126v, 127, 135v, 136, 144v, 155, 165v).

Noteworthy are the horizontal bands on ff. 49v, 53r, and 55v: here a row of small squares each with a letter; in a few cases these spell the name of the scribe: on f. 49v șlw ‘pray’, f. 53 ‘l ’yšw‘ q ‘for Yeshu ‘ p(riest)’, f. 55v yšw‘ qšy ‘Yeshu ‘ pri(est)’. This is the section that contains the colophon.

The illuminations throughout the manuscript are of the highest quality. They can be compared most closely with those in Birmingham University Library, Mingana Syr. 42, dated 1137 (Mingana, 1933) and in Lyons, Bibliothèque municipal, MS 1 (Boehm and Holcombe, 2016, no. 73, p. 157, ill). Compare also Leroy, II, no. 4, p. 11, with a similar Lectionary table, and p. 13 for a selection of quire numbers with geometric surroundings, typical of the period.

This manuscript dates from the period of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem under the reign of Queen Melisende (1105-1161) and her husband King Fulk V of Anjou. The Kingdom of Jerusalem was a Crusader state established immediately after the successful siege of Jerusalem in 1099 led by Godefrey of Bouillon during the First Crusade. Its first period dates from 1099 until 1187, when it was overrun by the Ayyubid Sultanate of Egypt under Saladin. Melisende’s reign as Queen extended from 1131 to 1153, and she was regent for her son Baldwin III between 1153 and 1161. Well known as a patron of the arts and a lover of books, she also endowed many Christian foundations, such as churches dedicated to saints Anne, James, and Mary (now Saint Mark), as well as Saint Mary Major (also known as Saint Mary Magdalene), where the present manuscript was transcribed. As Palmer has noted in his publication and analysis of a series of colophons in manuscripts produced by the Syrian Orthodox community (Palmer, 1992, pp. 74), Melisende was an ally of the Jacobites established in Jerusalem (Syrian Orthodox Christians).

Another manuscript, a large-format Breviary (Lyons, Bibliothèque municipal, MS 1), closely related stylistically to the present Lectionary, also comes from the monastery of Mary Magdalene and Saint Simon the Pharisee in Jerusalem and is dated February 10, 1138, just five years before the transcription of our manuscript. Its extensive colophon by the monk Michael describes the expansion of the monastery as a lodging for pilgrims and foreigners. Its illustration includes geometric bands as well as decorated circular indices that are strikingly similar to the present manuscript (Boehm and Holcombe, 2016, no. 73, p. 157, ill.; and Briquel-Chatonnet, 1997). When Saladin overran Jerusalem in 1187, putting an end to the first Latin Kingdom, he transformed the monastery of Mary Magdalene into a Muslim school, vestiges of which can still be seen through the floor in a store in Jerusalem. Palmer (1992, p. 93) relates an account that Jacobite monks from the monastery fled to Cyprus carrying with them manuscripts from the library. The Lyon manuscript was in Aleppo in the seventeenth century when it was given by the French consul to the city of Lyons. Although we cannot definitively trace the earlier history of our manuscript, it too comes from Aleppo. Might the two volumes have left Jerusalem together already in 1187?

The text of this Syriac Gospel Lectionary uses the translation of Thomas of Harqel (also Harquel, Harkel), who was bishop of Mabbug in Syria. Educated in Greek, he lived as an exile after being deposed as bishop in the Coptic monastery of the Enaton near Alexandria in Egypt. There, commissioned by Athanasius I Gammolo (active 594/595 or 603; died 631), he translated the Greek Bible with Paul of Tella. The Syriac translation of the New Testament was completed in 616 and is known as the Harclensis (or Harklean version), designated as ‘syrh’.

The Harklean translation is considered a masterpiece in its faithfulness to the original Greek. It is the only version to include the entire text of the New Testament. In the words of the German scholar A. Juckel: “This version is not simply a Syriac translation of its Greek Vorlage [predecessor]; it is a scholarly edition of the New Testament, furnished with a critical apparatus in the margin, the sort of work that is much appreciated by modern scholars” (Kiraz, 1996). Certain texts, previously excluded, were added to the Syriac Bible (2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, and Revelation).

Another Harklean Gospel Lection with very much the same contents as our manuscript (including an added lection for Saint Mary Magdalene) was copied in Jerusalem in 1173 (London, British Library Add. MS 7171). Small size Lectionaries are rare and were presumably meant for private use; other examples include British Library, Or. MS 4824 (11th-12th centuries) and Birmingham University Library, Mingana Syr. 42 (dated 1137), a Gospel manuscript adapted as a Lectionary, from much the same period.

Literature

Assad, Elias Malke. Pearls from Heaven The Assad collection of Syriac Manuscripts and Works of Art, London, 2015, no. 6, pp. 26-7 (publishing this manuscript).

Boehm, Barbara Drake and Melanie Holcomb, eds., Jerusalem 1000-1400. Every People Under Heaven, exh. cat., New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016, no. 73, p. 157, and p. 225ff.

Briquel-Chatonnet, F., Manuscrits syriaques de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France, de la Bibliothèque, de la Bibliothèque tque Mejanes d’Aix-en-Provence, de la Bibliothèque municipae de Lyon, et de la Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg, catalogue, Paris, 1997.

Brock, Sebastian P. An Introduction to Syriac Studies (3rd ed.) Piscataway, NJ, 2017.

Brock, Sebastian P. A Brief Outline of Syriac Literature, Kottayam, 1997.

Brock, “A Tentative Checklist of Dated Syriac Manuscripts up to 1300,” Journal of Syriac Studies 15.1 (2012), pp. 21-48.

Kiraz, George Anton. Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels: Aligning the Old Syriac Sinaiticus, Curetonianus, Peshitta and Harklean Versions, (3rd ed.), Leiden, 2004 (1st ed. 1996).

Leroy, J. Les manuscrits syriaques à peintures, Paris, 1964.

MinganaI, Alphonse. Catalogue of the Mingana Collection of Manuscripts, Vol. 1, Syriac and Garshuni Manuscripts, Cambridge, 1933.

Pahlitzsch, J. “St. Maria Magdalena, St Thomas und St Markus. Tradition und Geschicht dreier syrisch-orthodoxen Kirchen in Jerusalem,” Oriens Christianus 81 (1997), pp. 82-106.

Palmer, Andrew, “The History of the Syrian Orthodox in Jerusalem, I,” Oriens Christianus 75 (1991), pp. 16-43.

Palmer, Andrew. “The History of the Syrian Orthodox in Jerusalem, II,” Oriens Christianus 76 (1992), pp. 74-94; See also Syri.ac: An Annotated Bibliography (online).

Online Resources

e-GEDSH (Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition)

https://gedsh.bethmardutho.org/Harqlean-Version

We are grateful to Sebastian Brock for his contribution to this description.

TM 1347