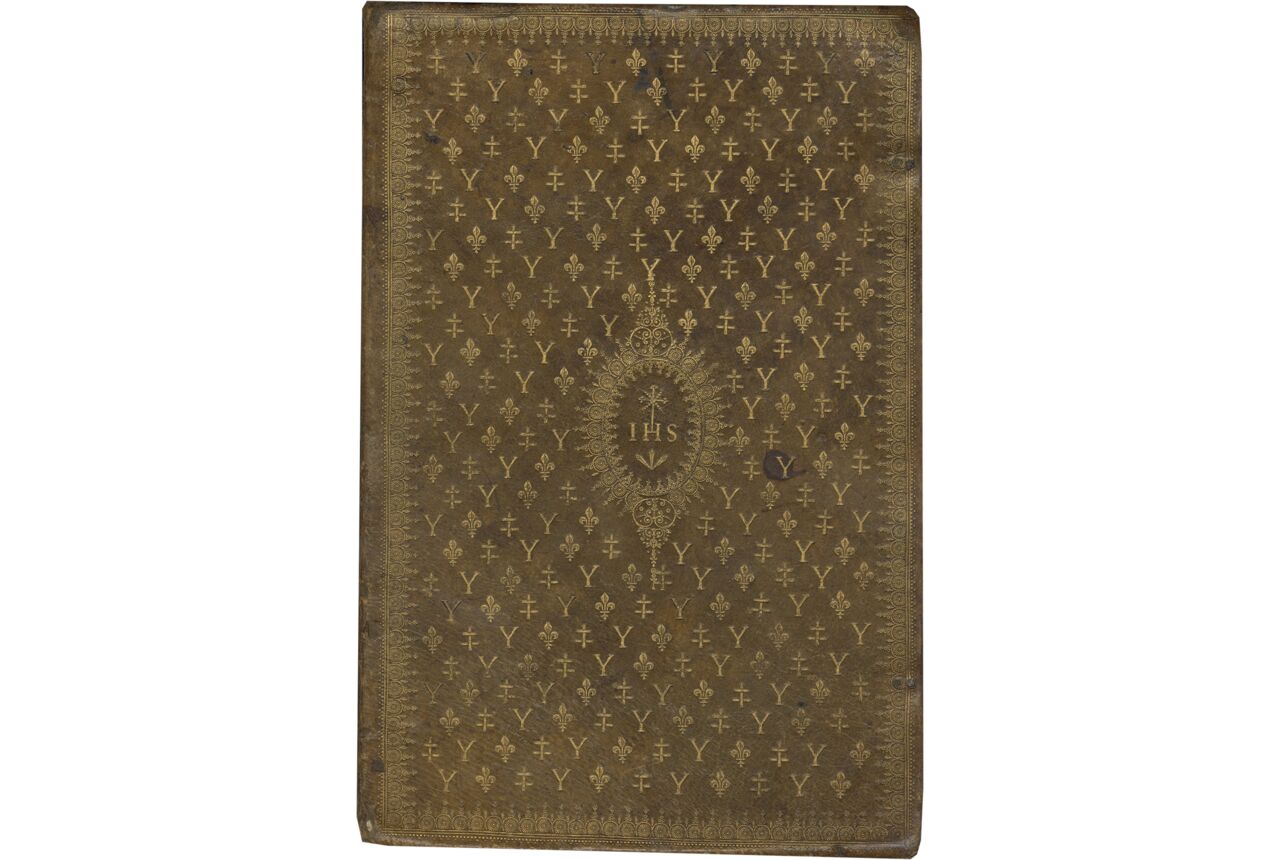

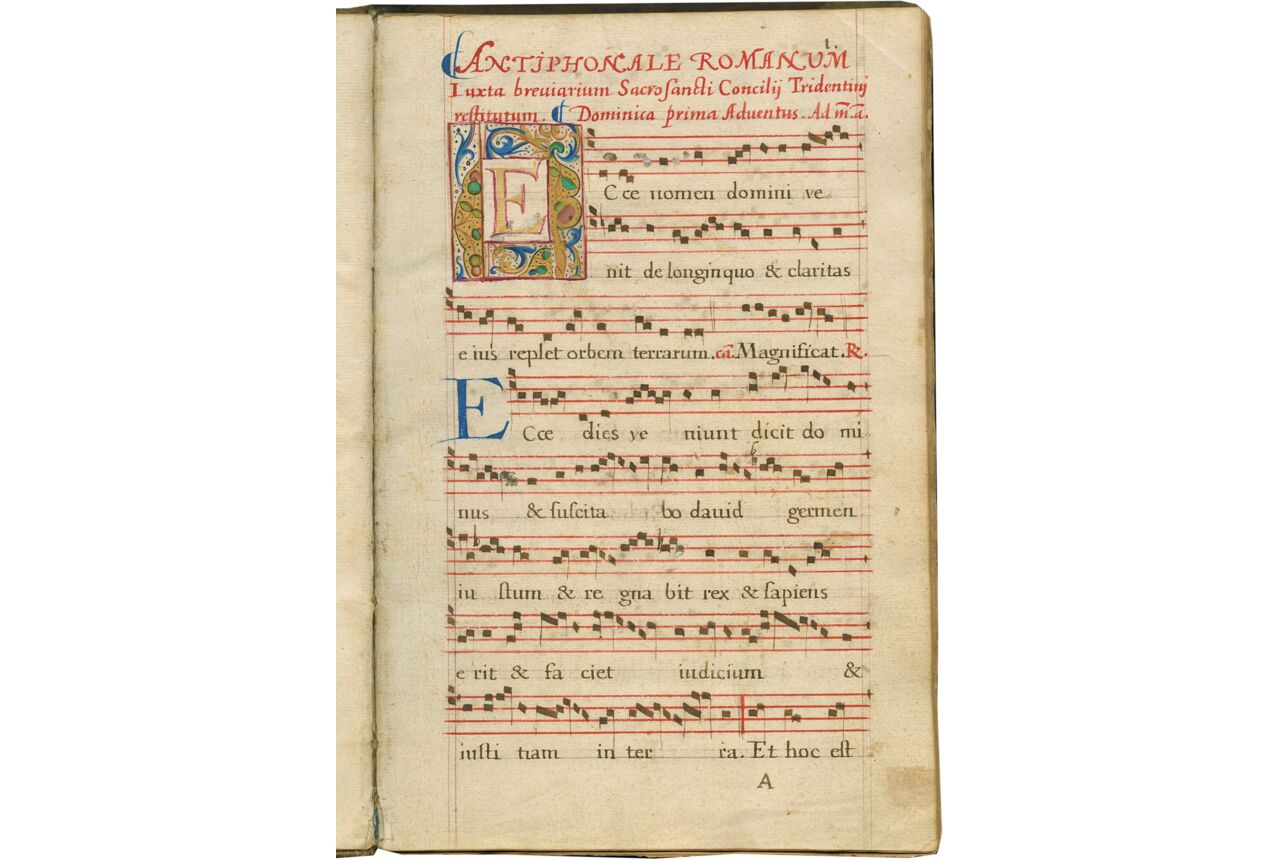

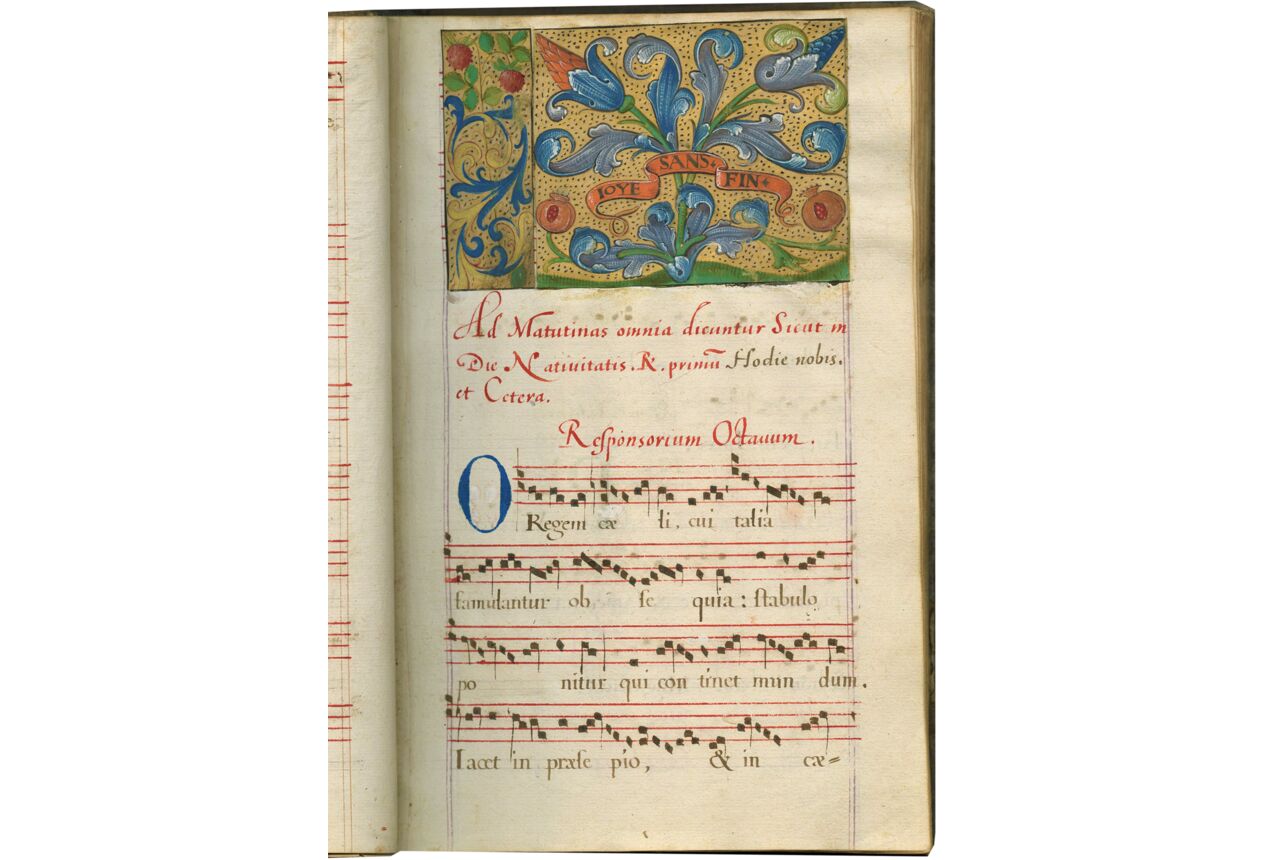

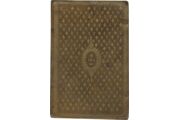

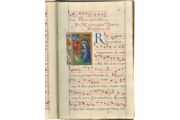

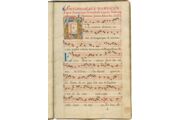

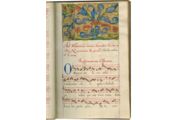

v (paper) + 174 folios + v (paper), foliated in Arabic numerals in ink, upper margin, with errors: 1-38, 38bis-118, 118bis, 119-120, 122-141, 4 unnumbered leaves, 1-24, 2 unnumbered leaves, supplemented by modern foliation in pencil, top outer corner recto [cited here], numbering the leaves following f. 141, 142-173, on paper, watermark, grapes with initials ‘SC’, similar to Briquet 13194, varieties of which were used from 1581-1603 mostly in France, including Blakenberghe (Belgium) 1581, Beauvais 1592-6, Troyes 1592-1603, Paris 1597 and others), (collation i8 [signed ‘A’ on f. 1] ii8 [-6, 7, 8, following f. 13, cancelled with no loss of text; 1-5, ff. 9-13, signed B1-B5] iii8+2 [1-7, ff. 14-21, signed B6-B12] iv3 [structure uncertain] v6 [1, f. 27, signed ‘C’] vi9 [structure uncertain, 1, f. 33, signed ‘D’] vii-xiii8 xiv8+1 xv-xxii8 xxiii-xxiv2), evidence suggests that the early quires of this manuscript were restructured in some way although the text is now complete, note that ff. 9-20 are signed B1-B12, although they are clearly now divided into two quires, there is a catchword at the end of the present second quire on f. 13, and stubs remain glued to f. 14, the first leaf of the third quire (with no loss, the antiphon beginning at the bottom of f. 13v, continues correctly on f. 14), with sewing visible after the fourth leaf, and a catchword on leaf eight, f. 21, followed by two additional leaves, quires 6-22 are signed on the first leaf with a capital letter, ‘D’ (f. 33) through ‘X’ (f. 162), and end with catchwords, ruled in ink with narrow double horizontal rules for nine lines of text (text copied between the rules, with ascenders and descenders extending above and below, and full-length double vertical bounding lines, (justification 227-225 x 137-135 mm.), written in an upright, formal, book hand modelled on Roman type with nine four-line red staves and nine lines of text per page by at least two scribes (second scribe beginning on f. 141v), and possibly a third scribe copying the last few folios, music in square notation, red rubrics in a cursive script, red running titles (Common of Saints only), numerous red and blue initials one-line to the equivalent of one-line of text and music, two large brushed gold initials, bordered in red, ff. 1 and 146, otherwise all decoration was cut from parchment manuscripts and glued in spaces left blank by the scribe: three initials, possibly from other manuscript sources: f. 91v, 2-line gold initial, infilled with blue with white highlights in a narrow gold frame, f. 97, 1-line gold initial with an acanthus border extending into the upper margin from the usual parent manuscript, and f. 103, equivalent to one line of text and stave, modeled blue initial infilled and on a square red ground with gold highlights, acanthus borders are also used on f. 1, square acanthus border surrounding the initial, f. 28v, small square from an acanthus border used as a line-filler, and f. 108, two rectangle serving as borders in the top line and inner margin, two folios with very large decorative motifs (likely from a very large manuscript, and not the manuscript that supplied the other miniatures and acanthus borders): f. 28, large frontispiece in the top half of the page, 134 x 84 mm., assembled from two decorative panels, with bold floral decoration and acanthus on a dark gold-colored ground, with motto, “Ioye Sans Fin” and f. 96v, two large square of decorative motifs, 83-90 x 100 mm., one in the shape of a fleur de list infilled with pansies, and the second, possibly initials (‘v’ ‘v’), TWENTY VERY FINE INSERTED MINIATURES, beautifully painted in vivid colors and gold, including one large Crucifixion, ten with borders (described below), small oxidized text correction in white on f. 23v, small tear in lower margin of f. 105, quire three is loose, ff. 172-173, outer margin trimmed, some stains and cockling (where illuminations were glued onto the paper), overall in good condition. ORIGINAL BINDING of olive-green morocco with handsome semé gilding of small stamps of fleur-de-lis, cross of Lorraine (croix de Lorraine), and ‘Y’s covering both covers and the spine, set within gold borders of delicate fleurons and with a center piece with the “IHS” monogram, gilt edges, marbled pastedowns, slightly stained, edges worn, once with two clasps, now removed, housed in modern custom black leather case with title in gilt and date on spine. Dimensions 272 x 180 mm.

This hybrid manuscript is highly unusual, combining a musical text written in the last quarter of the sixteenth century with cut-out illuminations from the beginning of the century. Carefully planned from the beginning, the production was always intended to accommodate these illustrations, perhaps from another damaged(?) manuscript owned by the well-to-do patron. We cannot know for sure what the host manuscript was, but the miniatures and decorated borders are securely attributed to the Master of Philippe of Guelders and his workshop. Manuscripts illustrated with miniatures cut from previously made manuscripts are a fascinating little-studied subset of the genre book historians call hybrid manuscripts.

Provenance

1. Written in France in the late sixteenth century, c. 1570-1600, based on the evidence of the script and, to some extent, the watermark by comparison with similar forms; the opening rubric establishes that this was copied after the reforms mandated by the Council of Trent, allowing us to date it after 1568 (the date of the new, reformed Breviary).

The Office for St. Joseph, observed March 19, concludes the Sanctoral, following directly after the Annunciation (March 25), and perhaps suggesting that this manuscript was copied c. 1570 or later (the Feast was observed locally earlier, and included in the Breviary mandated by Trent, but it was not established throughout the church until 1570.)

Our manuscript is handsomely illustrated with inserted miniatures cut from an earlier manuscript by the artist known as the Master of Philippe of Guelders, active in Paris in the first decade of the sixteenth century, or his workshop. The manuscript was meticulously planned for these miniatures.

The quality of the illumination and the manuscript’s lavish binding suggest this was destined for someone of wealth and status, possibly someone from the noble House of Lorraine, perhaps as a gift for a church associated with the family, although at present we have not identified this individual (someone, presumably, whose name began with “Y”). Two facts make this an attractive hypothesis. First, Renée de Lorraine (1585-1621), the daughter of Henri of Lorraine, third Duc de Guise, Marie-Louise d’Aspremont (d. 1692), Duchess of Lorraine, daughter of Charles de Nanteuil and wife of Charles de Lorraine, and Henriette de Lorraine (1592-1669), the daughter of Charles de Lorraine, Duc d’Elbeuf, all owned books with elaborate bindings in the same general style as the binding of our manuscript, i.e. bindings with semis decoration that includes the Cross of Lorraine and initials either on their covers or, in one case, used for the pastedowns (Guigard, 1890, vol. I, 120). Secondly, the close connection of the artist of the inserted miniatures with members of this family, suggests that the early sixteenth-century manuscript that was the source of the miniatures could still have been owned by the family and thus available to makers of our volume.

Evidence seems lacking for the alternative theory suggested by some earlier descriptions that this binding was made for Ysabel Clara Eugenie (1566-1633), daughter of Philipp II. of Spain, wife of Albert VII, archduke of Austria, ruler of the Spanish Netherlands.

2. Overall, quite clean, with few signs of use, apart from a few corrections; on ff. 8v-12, and ff. 154v-155, the musical notation has possibly been corrected.

3. Inside front cover, clipping from a sales catalogue in English, “Antiphonale Romanum juxta Breviarium …, formerly the property of Ysabel Clara Eugenie, daughter of Philip II of Spain, brown Morocco, covered with gold fleur-de-lys and Y’s (the initials of her name).”

4. Previous owners’ and dealers’ annotations include, front flyleaf, f. i, in pencil,”1/10” (circled); front flyleaf, verso: also in pencil, “97m(?)”; “2027”; “1,20,0,<7?>”; verso of last back flyleaf, “67/58.”

5. Hamburg, F. Dörling Auction 119, 2-4 December 1986, lot 1 (unverified; Schoenberg Database 1223).

6. London, Christie’s, July 9, 2001, lot 32 (unverified; Schoenberg Database 31858).

Text

ff. 1- 91v, Temporal, beginning with the rubric, Incipit Antiphonale iuxta brevariarium Sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini restitutum, from the first Sunday in Advent through the fifth Sunday after Easter;

Includes Christmas beginning on f. 15, the Feast of St. Stephen on f. 23v, St. John on f. 27, and the Holy Innocents (rubric lacking), followed by Sunday in the Octave of Christmas, continuing to the top of f. 27v, with the remainder of the page left blank; on f. 28, the Office continues with responses for Matins, and then the text proceeds through the usual feasts of the Temporal, including among others, f. 36, Epiphany, f. 52, First Sunday in Lent, f. 83v, Easter, f. 87v, Dominica in albis, and then continuing and concluding with the fifth Sunday after Easter.

ff. 91v-96v, Dedication of a Church;

ff. 97-105v, [Continuation of the Temporal], Ascension and Pentecost;

ff. 106-145v, Sanctoral, beginning with the rubric, Proprium sanctorum, Pars hiemalis, from the Vigil of St. Andrew (November 30) through the Annunciation (March 25) and Joseph (March 19), which begins on f. 142 in a new hand, and concludes mid f. 144; [remainder and ff. 144v-145v, blank staves];

Includes full Offices for Conception of Mary, Purification, the feast of St. Benedict, and the Annunciation.

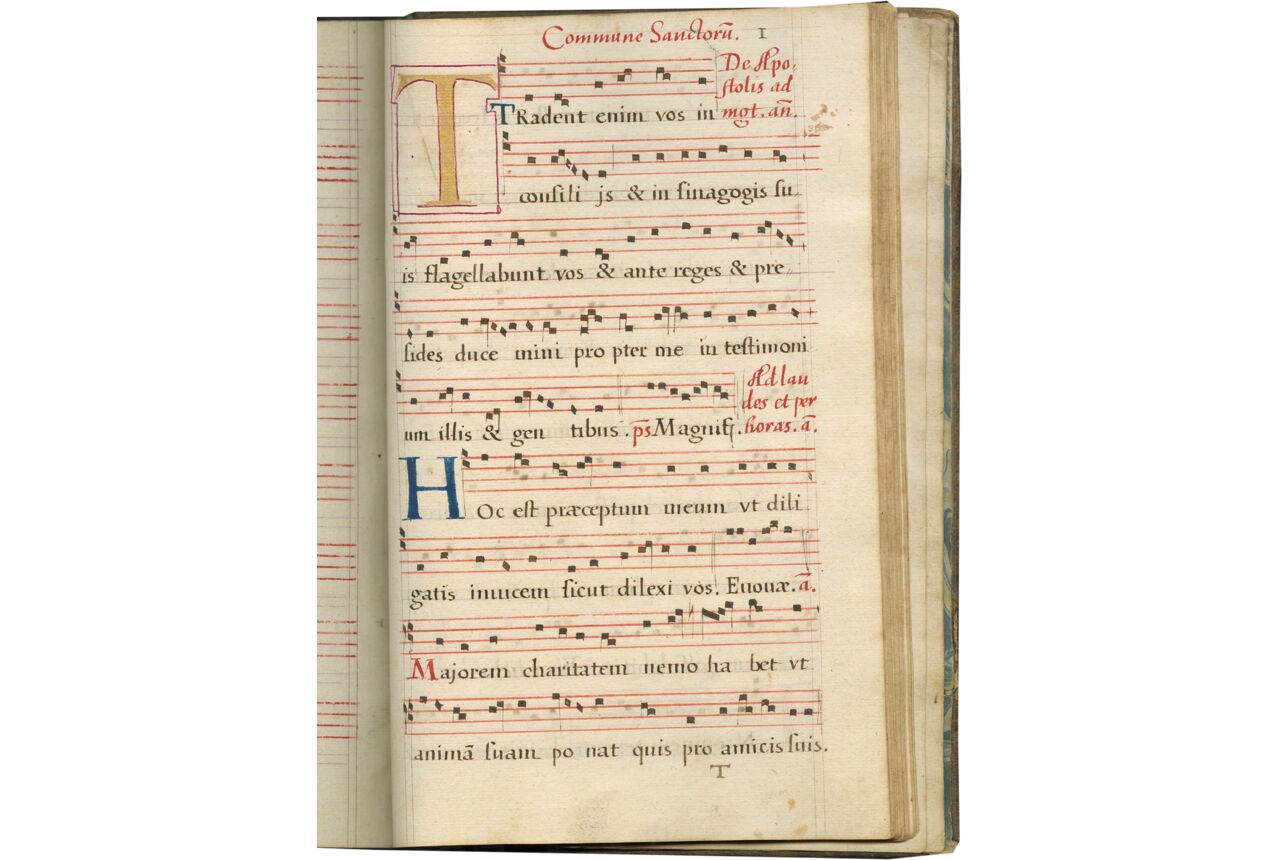

ff. 146-167v, Common of Saints;

ff. 168-170v, Office of the Virgin Mary;

ff. 170v-173, Office de Saint Joseph, …; [ending mid-f. 173, remainder and f. 173v, blank but ruled].

Illustration

The scribe who copied this manuscript, as one would expect, left blank spaces for the illumination. The illumination in this case, however, was not added by a contemporary artist painting directly in these blank spaces but was instead provided by cutting out miniatures and borders from at least three different manuscripts from the early sixteenth century and gluing them into the blank spaces.

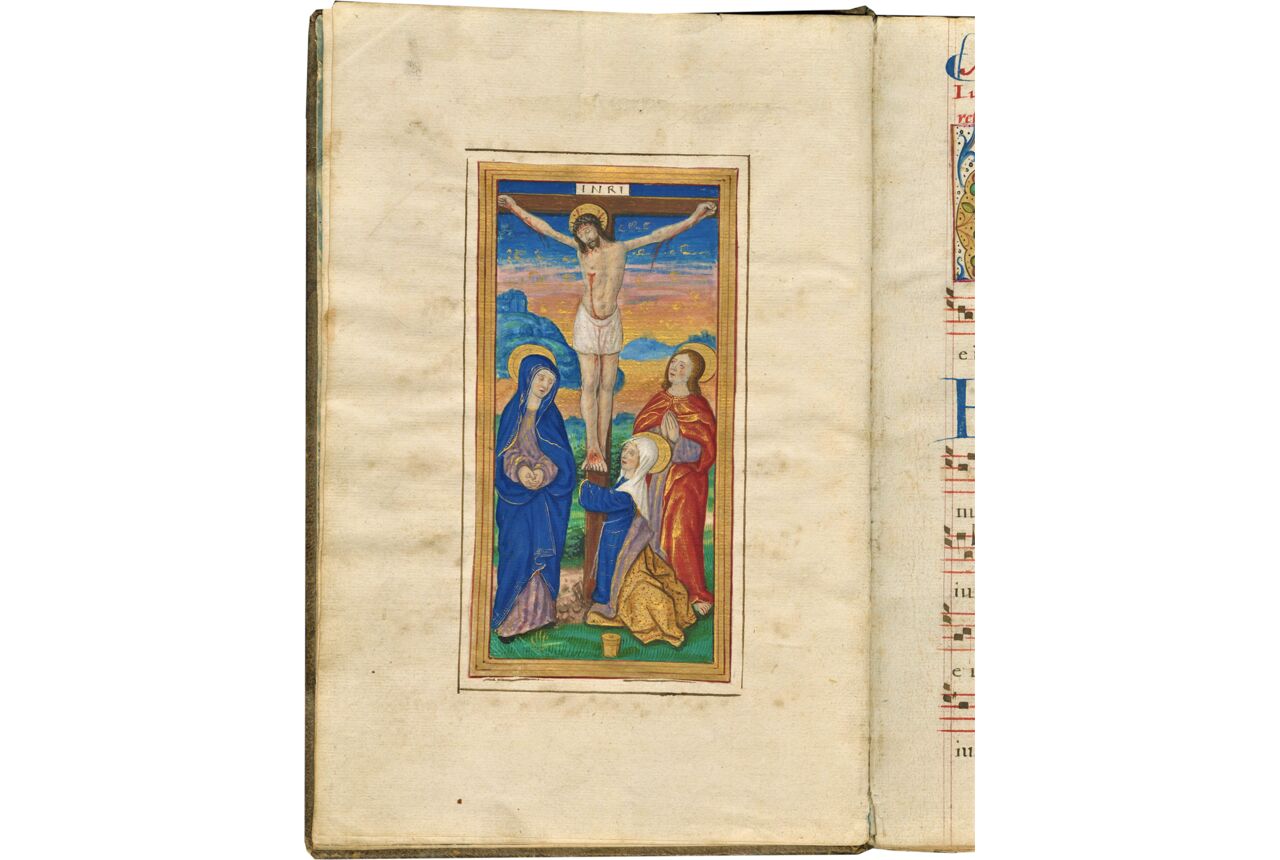

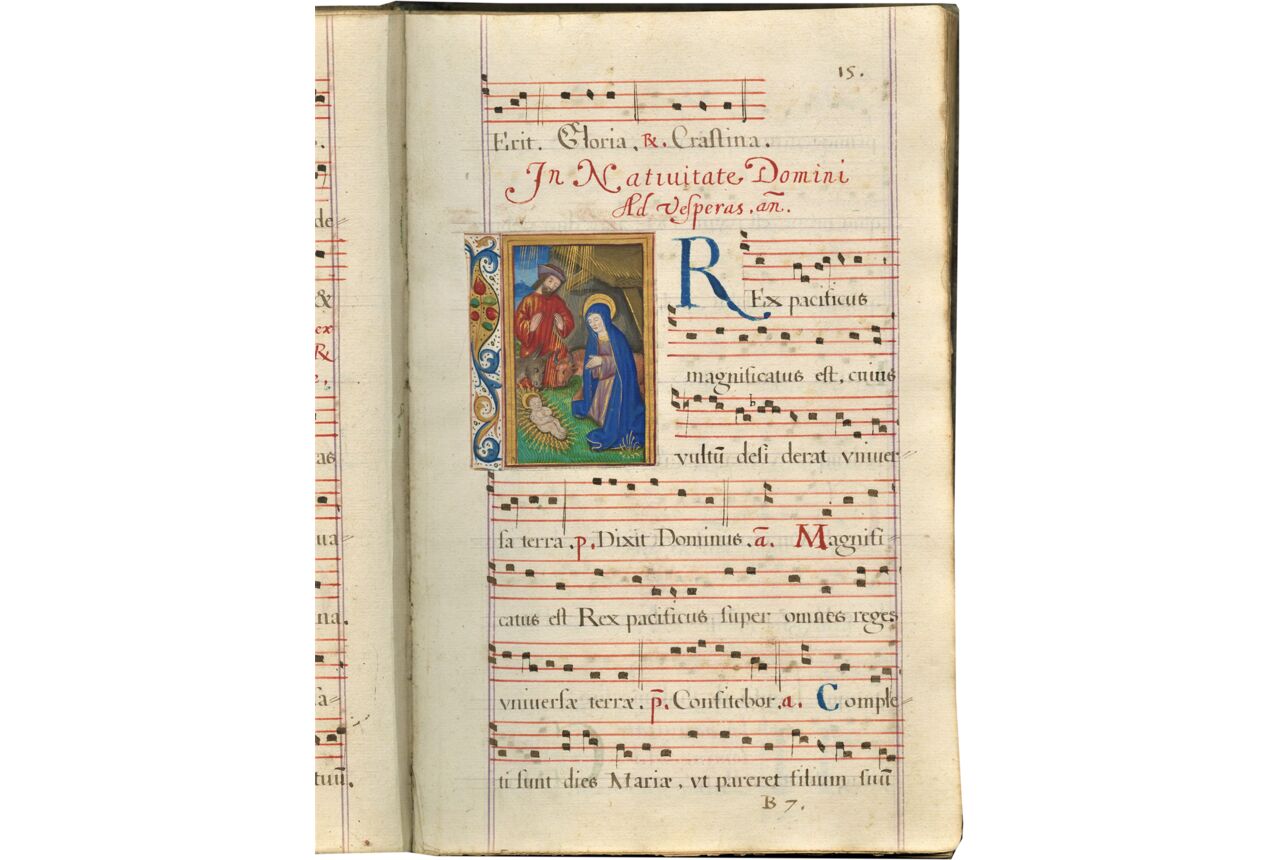

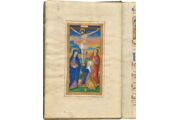

The miniatures (all but two of the miniatures cut from the same manuscript) are executed in deep rich colors including blue, red, violet, green, with brushed gold used for highlights in the draperies and sky, featuring figures with small mouths that are richly dressed, with particular attention paid to fabrics, some with tear-shaped gold highlights, and others painted as brocade, ermine, and so forth. The two miniatures on f. 106 of standing saints were cut from a different manuscript and differ from the others in their tall, narrow format, the background of deep blue with gold stars, and the arched gold frames. All the remaining miniatures are in rectangular gold frames, and ten are accompanied by borders of blue and gold acanthus on uncolored grounds strewn with black dots interspersed with gold disks, alternating with naturalistic flowers and leaves on gold grounds. These borders were cut from the same manuscript as the miniatures (the border on f. 62v is still connected to the miniature), but most of the borders are independent strips glued alongside, on the top, or below the miniature. A few miniatures retain tiny painted initials in their borders (e.g. ff. 54v, 58v). The decorative cuttings on ff. 28 and 96vv are similar in style but were cut from a third contemporary manuscript that must have been very large (a Choir Book is likely) given their scale.

The style of the miniatures allow us to securely attribute them to the Master of Philippe of Guelders, or artists from his workshop; the level of execution in the miniatures varies (the large Crucifixion miniature opening the manuscript is very fine, as are a number of others, for example, the Pietà on f. 72v; others are more quickly executed on a smaller scale, with less attention to detail). This artist takes his name from his work in a manuscript of the Vie de Christ, a French translation of the Vita Christi by Ludolphus of Saxony, now Lyon, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 5125, see Online Resources, and Avril and Reynaud, 1993, no. 152), made in 1506 for Philippa of Guelders (1464-1547), the second wife of René, Duke of Lorraine, and the great grandmother of Mary Queen of Scots (on this artist, see Avril and Reynaud, 1993, pp. 278-281; and Pächt and Thoss, 1977; and Plummer, 1982). Reynaud states that the suggestion that he worked in Rouen for a time was based on a misinterpretation, and everything instead points to activity in Paris in the first decade of the sixteenth century, including his collaboration with Parisian artists such as Jean Pichore, his employment to illustrate printed books by Antoine Verard, and his clients, which included, in addition to the Duchess of Lorraine, Louis XII and cardinal Georges d’Amboise. Stylistic links suggest he may have trained in Bourges. Characteristic of his works are round faces, astonished eyes, snub noses, and very small mouths, together with intense colors, plentiful use of liquid gold on drapery and architecture, and fabrics decorated in patterns of golden tears (Avril and Reynaud, 1973, p. 278). Other manuscripts attributed to him include: Huntington Library, HM 1101, a Book of Hours, Paris BnF, MSS fr. 702, 54, 2678-9, and Vienna, ÖNB, Cod 2582, and Cod. 2565. For the most part his illumination is found in secular manuscripts; the religious miniatures preserved in our manuscript are thus an important addition to his oeuvre and should be studied alongside those of the Vie de Christ in Lyon and the Book of Hours at the Huntington.

These added miniatures are securely pasted down, but some of their text can be read by shining a light through the paper page. A preliminary analysis tells us that the parent manuscript was in Latin; the text on verso of the miniature on f. 36 (Adoration of the Magi), is from the “Psalterium Maius Beatissimae Mariae Virginis,” attributed (spuriously) to St. Bonaventure, suggesting the miniatures once illustrated a devotional manuscript, such as a Prayer Book, a Book of Hours, or even a Psalter.

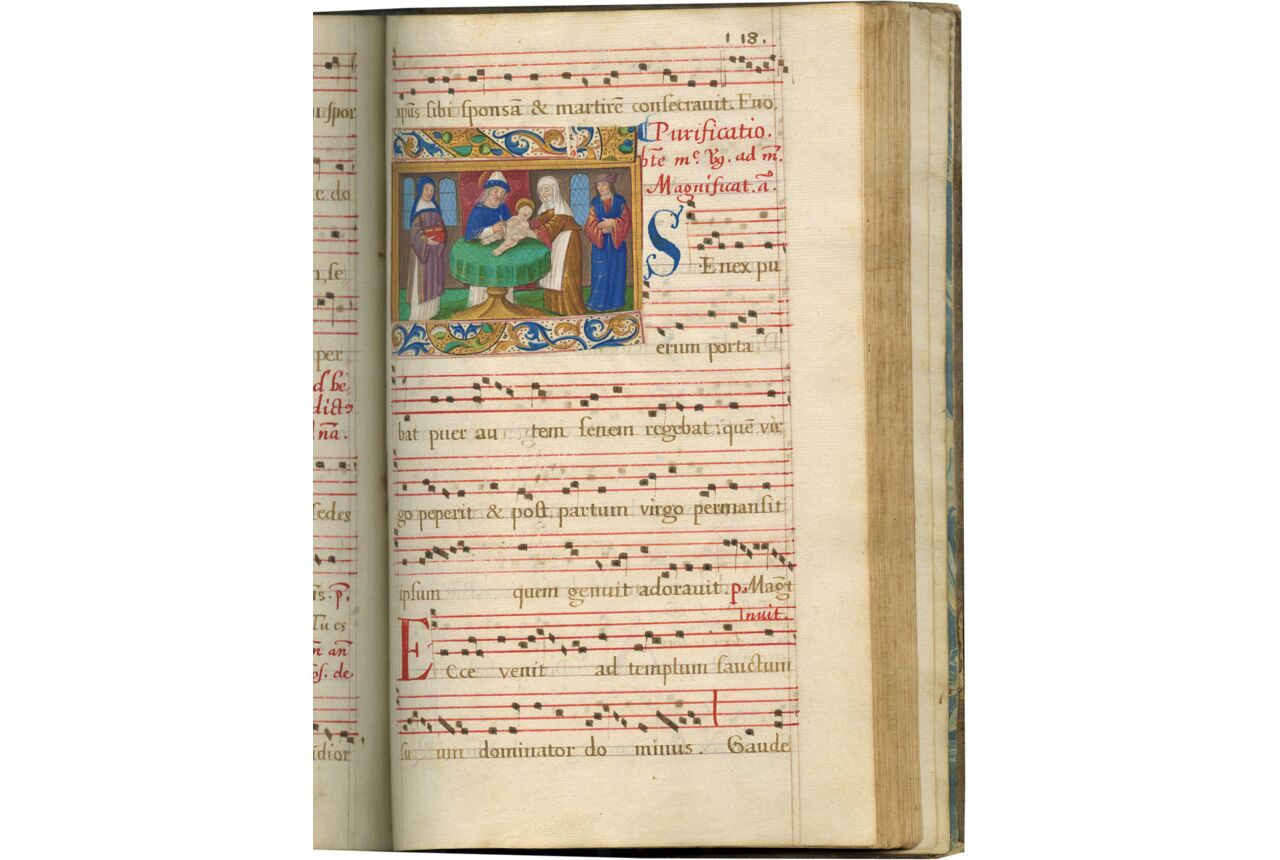

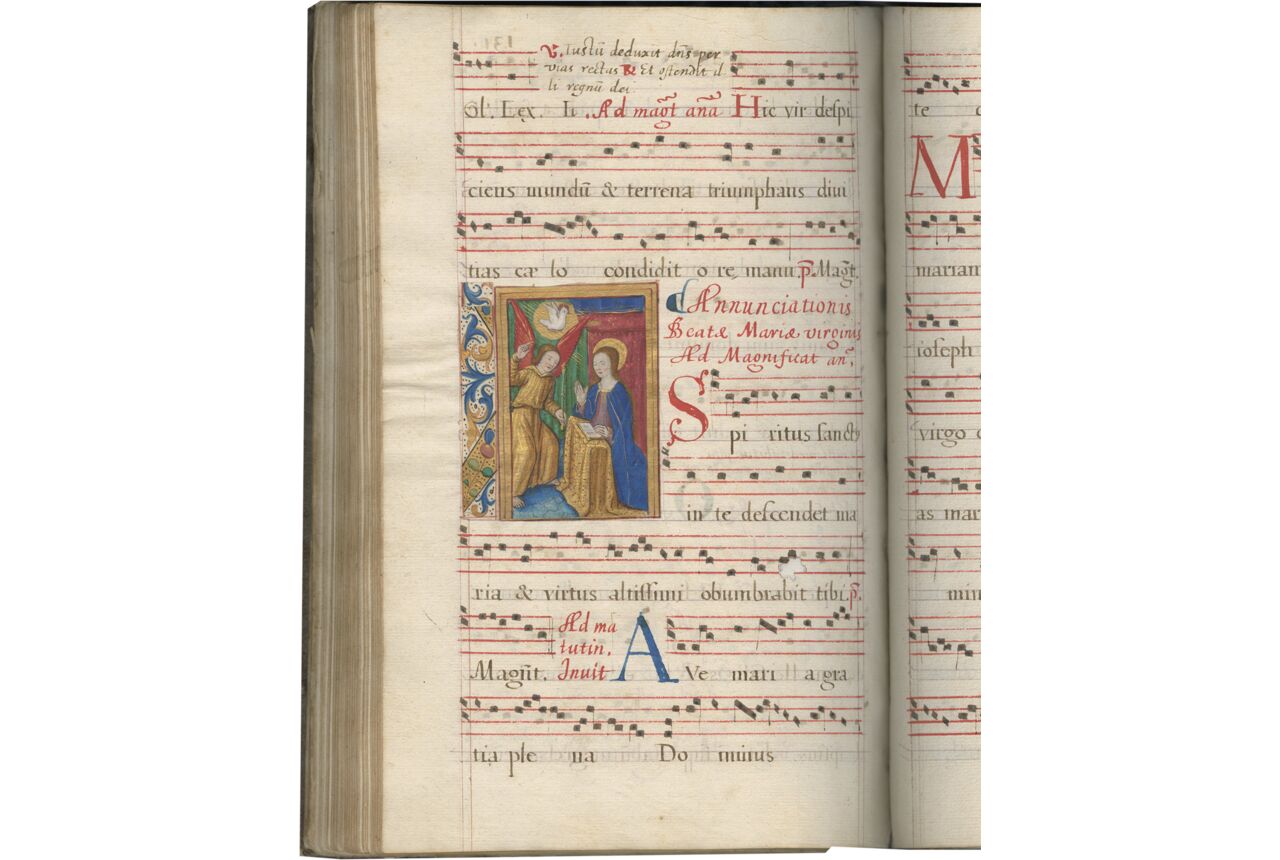

Subjects as follows:

[front flyleaf, f. iv verso, facing f. 1], Large miniature of the Crucifixion, in a gold frame, 166 x 85 mm.;

f. 15, (Christmas) Nativity, equivalent to three lines of text and music, 75 x 50 mm., in a gold frame, with a narrow acanthus border alongside in the inner margin;

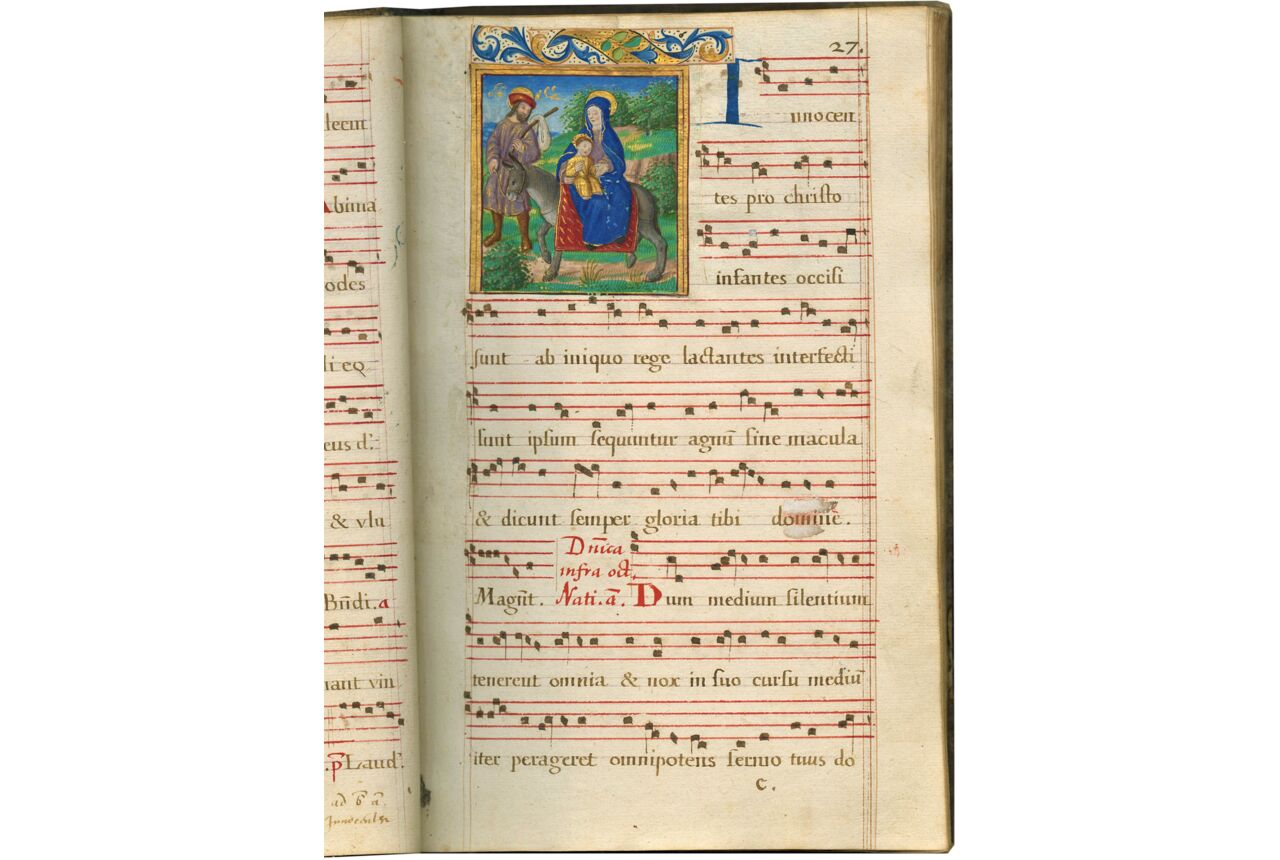

f. 27, (Holy Innocents) Flight into Egypt, equivalent of three lines of text and music, 74 x 72 mm., acanthus border pasted above;

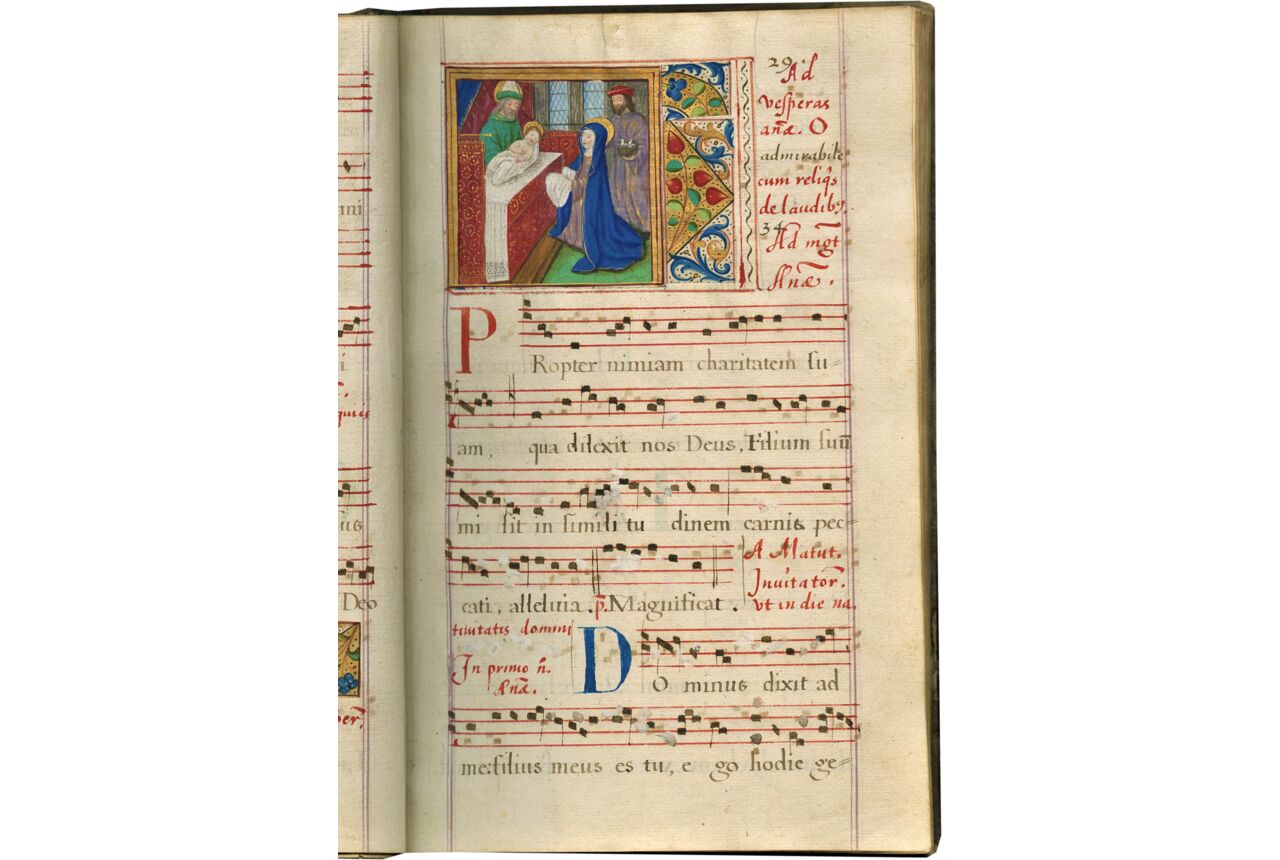

f. 29, (Circumcision) Presentation in the Temple, 70 x 74 mm., with border on the right edge;

f. 36, (Epiphany) Adoration of the Magi, 56 x 74 mm., with border upper margin;

f. 52v, (First Sunday in Lent), Christ and Mary, 84 x 55 mm.;

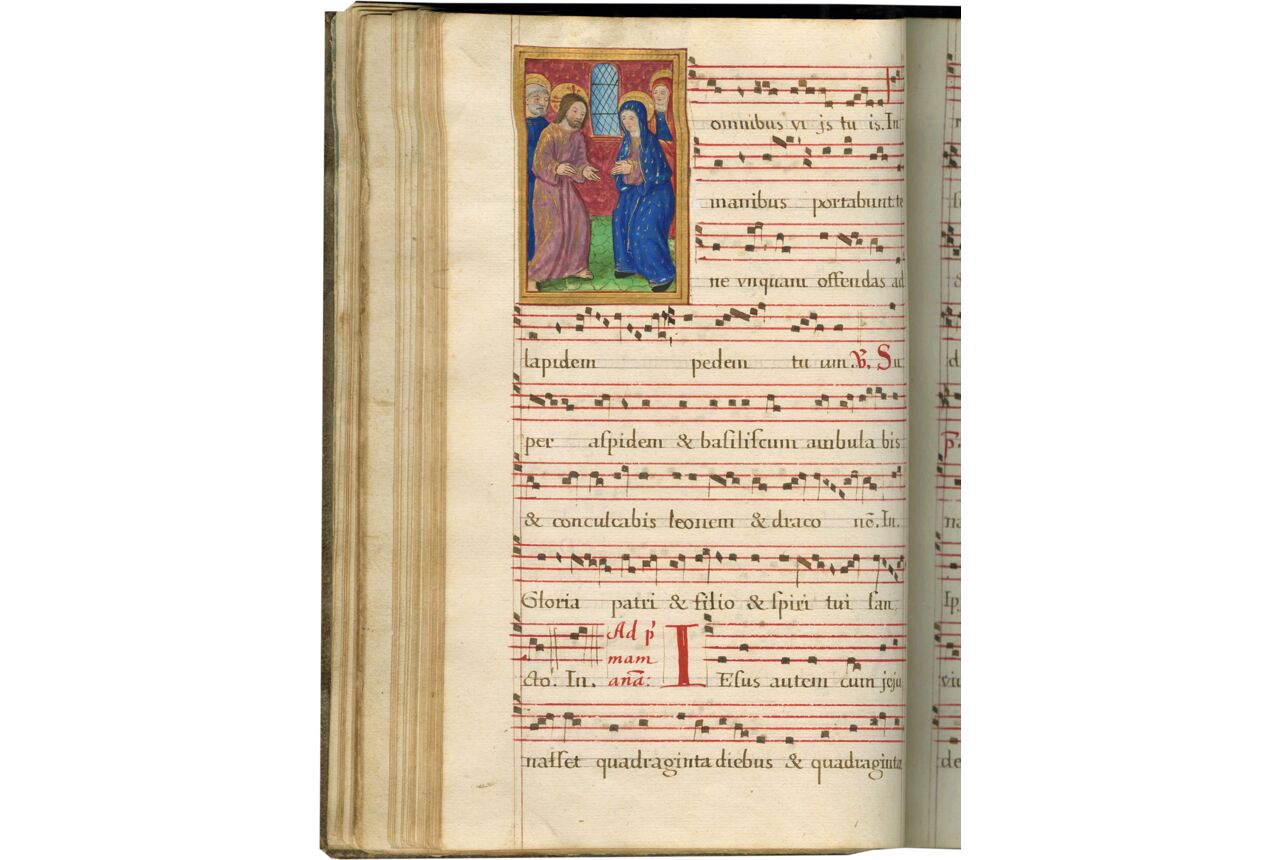

f. 54v, (Second Sunday in Lent), Christ with a sinner(?) surrounded by apostles, 76 x 74 mm.;

f. 56v, (Third Sunday in Lent), Christ and the woman from Samaria at Jacob’s well, 70 x 86 mm.;

f. 58v, (Fourth Sunday in Lent), The young Jesus in the temple with the teachers, with a narrow border on the right, 55 x 45 mm.;

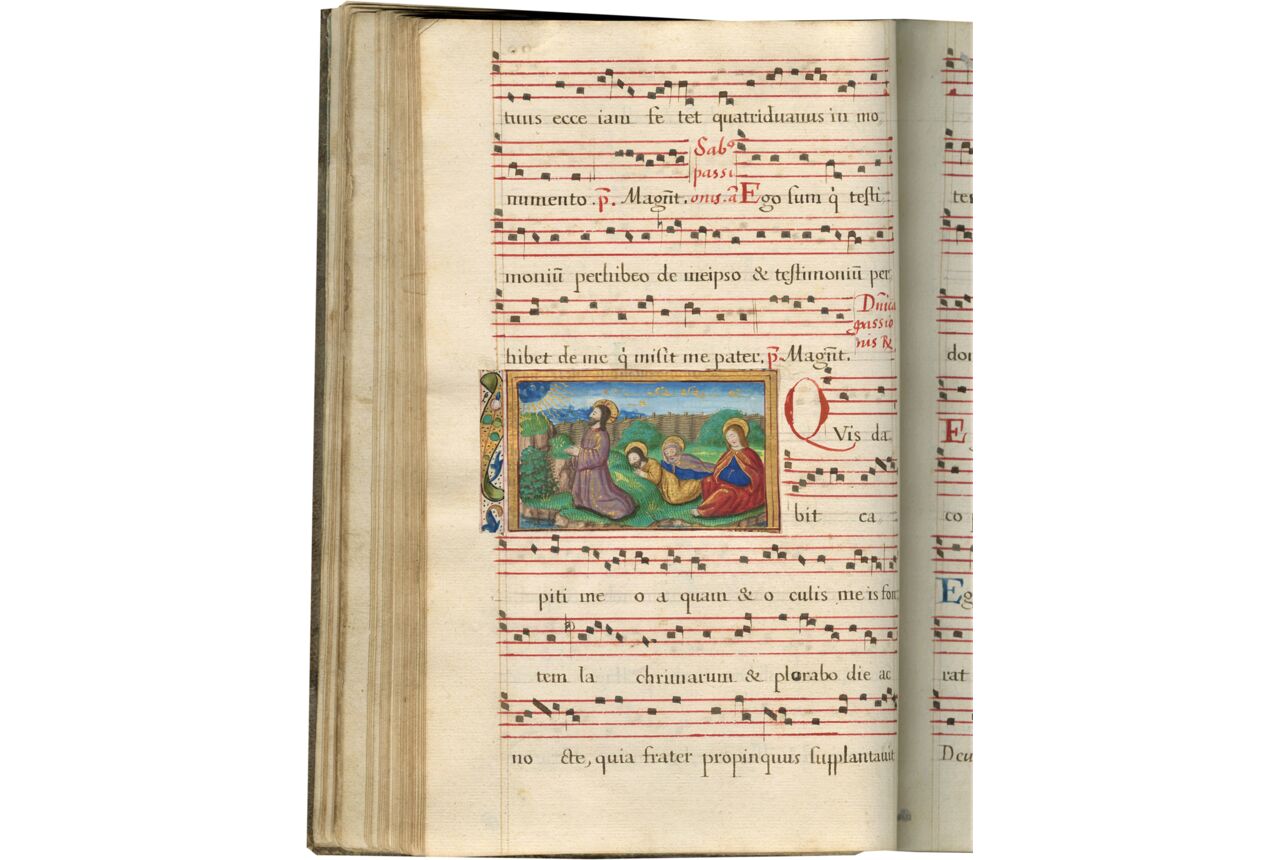

f. 60v, (Passion Sunday) Christ praying in the Garden of Gethsemane, 52 x 88 mm.; border on the left;

f. 62v, (Palm Sunday), Carrying of the cross, 45 x 88 mm., with a border on the left;

f. 66, (Maundy Thursday, Holy Week), Christ is nailed to the cross, 80 x 55 mm.;

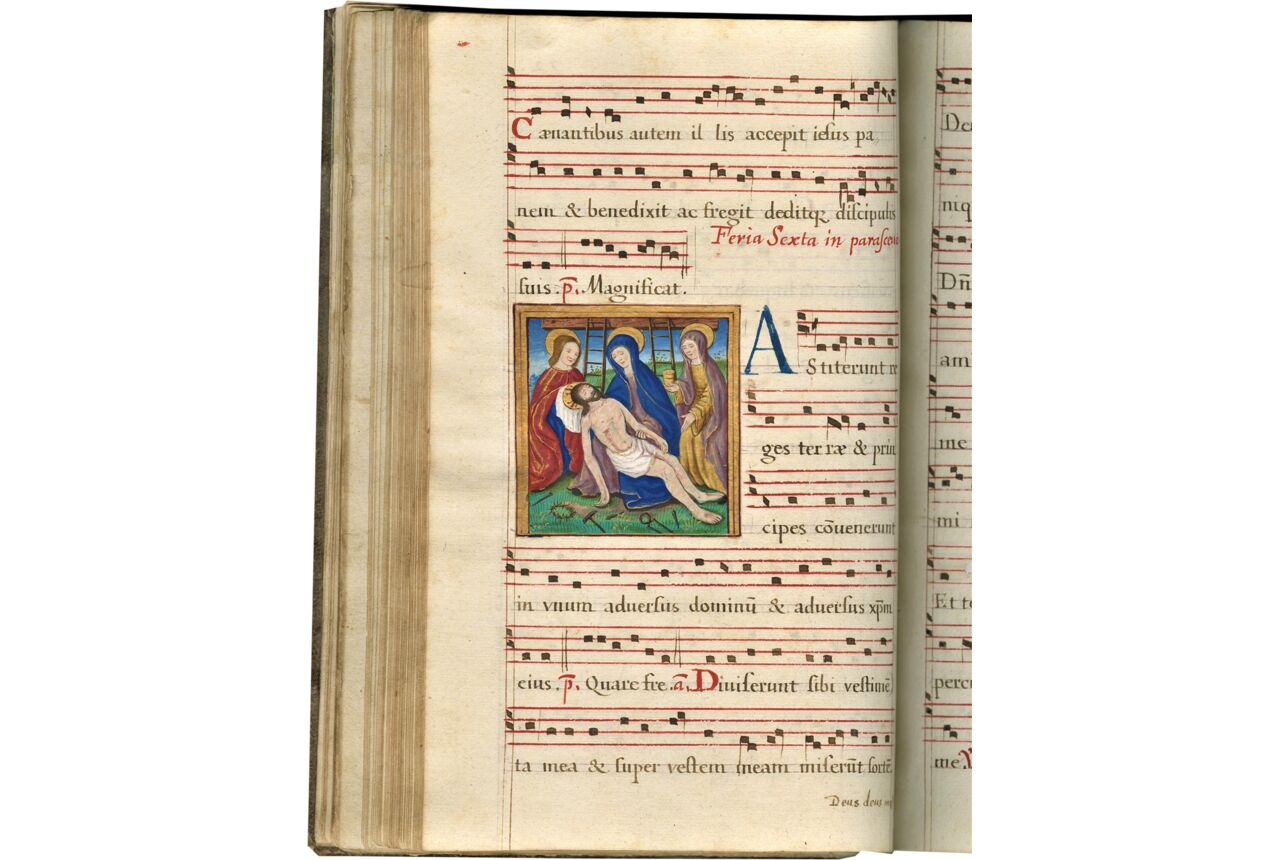

f. 72, (Good Friday, Holy Week), Pietà, 75 x 72 mm.;

f. 78v, (Holy Saturday), Entombment, mounted horizontally instead of vertically, 80 x 52 mm.;

f. 83v, (Easter), Christ as the gardener and Mary Magdalene with the jar of ointment; 78 x 86 mm.

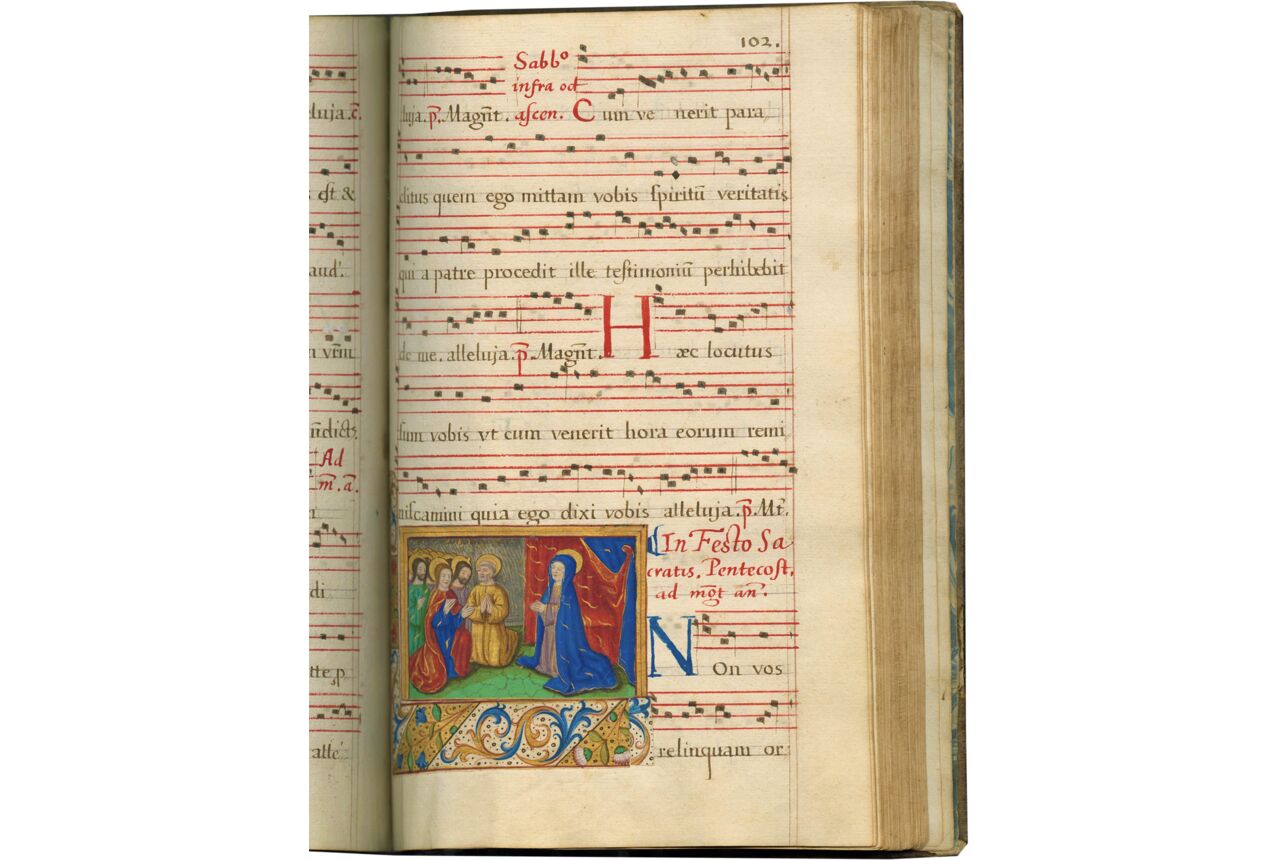

f. 102, (Pentecost), Pentecost, 56 x 88 mm.; with angle border, in the inner margin and below the miniature;

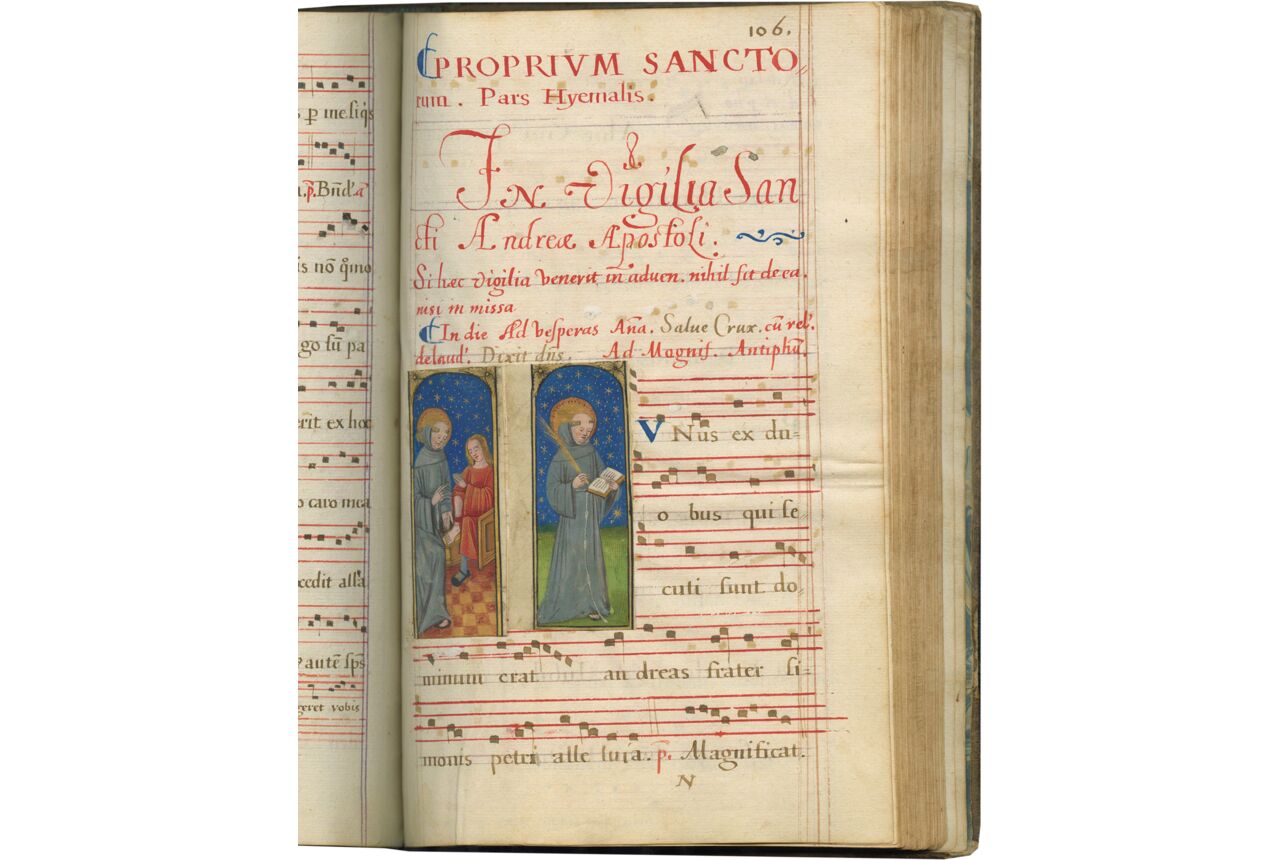

f. 106, (Beginning of the Sanctoral), Two miniatures, each 86 x 32 mm.; with St. Anthony of Padua on the left, healing the boy with the detached foot; and a standing Franciscan saint on the right;

f. 118, (Purification), Circumcision, top and bottom with border, 52 x 88 mm.;

f. 131v, (Annunciation), Annunciation, 75 x 52 mm., with a border on the left.

This manuscript is an Antiphonal, or Antiphonary; in contrast to Breviaries, Antiphonals omit the spoken texts and include only the texts and music for sung portions of the Divine Office. It takes its name from the texts known as antiphons, which are verses, usually from the Psalter, sung before and after the Psalms or the Magnificat during Matins and Vespers. A reform of the Breviary, proposed at the Council of Trent (1545-1563) was subsequently undertaken by a commission appointed by Pope Pius V; the new reformed Breviary appeared in 1568, and as stated in the opening rubric, our volume follows the Office proposed in this Breviary (on these reforms see Geldhof, 2017; Ditchfield, 1999; and Smith, 2018). For practical reasons, liturgical books often include texts for only part of the year; our manuscript has been described as a “Winter Antiphonal,” which is true in a general way. Liturgical volumes for the winter season (pars hiemalis) are defined today as containing texts for Advent up until the first Sunday in Lent. Our manuscript includes a much more extensive section of the Temporal (through the Fifth Sunday after Easter, Advent, and Pentecost), with a shorter Sanctoral, which concludes with the Annunciation (March 25) (the feast of St. Joseph follows, although it is observed on March 19).

Manuscripts decorated by pasting in printed woodcuts and engravings have been discussed in the literature (Erler, 1992; Hindman and Farquhar, 1977; Hindman, 2009; Schmidt, 2003; Rudy, 2015 and 2019; see also McKtterick, 2003). Hybrid manuscripts decorated with miniatures, initials and borders cut from other manuscripts, in contrast, are less common and have not yet been the subject of a comprehensive survey. The nuns of the English Bridgettine Abbey of Syon cut out initials from their manuscripts to paste into other manuscripts (De Hamel, 1991; Alexander, 1992, p. 49). The Augustinian canonesses at Sint-Mariëndaal in Diest (North Brabant), and the nearby convent of Soeterbeeck, also decorated their books in this fashion in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century (Rudy, 2015, pp. 106-108). Pasted-in initials are found in a manuscript copied by the Cistercian nuns at Medingen in Lower Saxony in the late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Don.e.48). Other examples include: London, Victoria and Albert, Reid MS 51, a German Collectar, and a Commentary on the Mass in German c. 1596, sold at Sotheby’s, 29 November 1990, lot 126 (cited in Alexander, 1992, note 77); and two manuscripts described on this site, a sixteenth-century Noted Antiphonal (Augustinian Use) from the Southern Netherlands or Germany (formerly TM 717) and a hybrid Ritual for Carmelite nuns Belgium, c. 1600 (formerly TM 875).

As noted above, there is no comprehensive survey of manuscripts illustrated with decoration cut from other manuscripts (the manuscripts listed above are examples only), and it is premature to draw conclusions. Nonetheless, based on our present, incomplete, knowledge we can note that most known examples are from the Low Countries and Germany, and that many were made by nuns. The manuscript described here appears to stand apart from this group for its expense, for its extensive use of numerous high-end miniatures, and for its origin in France.

Literature

Alexander, J. J. G. Medieval Illuminators and Their Methods of Work, New Haven ,1992.

Avril, François, Nicole Reynaud. Les manuscrits à peintures en France, 1440-1520, Paris, 1993.

Breviarium Romanum: Editio princeps (1568), ed. M. Sodi, and A. M. Triacca, Vatican City, 1999.

De Hamel, Christopher. Syon Abbey: the Library of the Bridgettine Nuns and Their Peregrinations after the Reformation: An essay, Otley, England, 1991.

Ditchfield, S., “Giving Tridentine Worship Back Its History,” in Continuity and Change in Christian Worship, ed. R. N. Swanson, Studies in Church History 35, Woodbridge, 1999, pp. 199–226.

Erler, Mary. “Pasted-in Embellishments in English Manuscripts and Printed Books, c. 1480-1553,” The Library, sixth series14 (September 1992), pp. 185-206.

Geldhof, J. “Trent and the Production of Liturgical Books in its Aftermath,” in The Council of Trent: Reform and Controversy in Europe and Beyond (1545-1700), vol. 1: Between Trent, Rome and Wittenberg, Göttingen, 2018, pp. 175-189.

Guigard, J. Nouvel Armorial du Bibliophile: guide de l'amateur des livres armoriés, Paris, 1890, vol. I, p. 120.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k77498r/f142.item

Harper, John. The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century, Oxford, 1991.

Hiley, D. Western Plainchant: A Handbook, Oxford, 1993.

Hindman, Sandra, and James Douglas Farquhar. Pen to Press: Illustrated Manuscripts and Printed Books in the First Century of Printing, College Park, 1977.

Hindman, Sandra. Pen to Press. Paint to Print. Manuscript Illumination and Early Prints in the Age of Gutenberg, Les Enluminures, 2009.

Hughes, A. Medieval Manuscripts for Mass and Office: A Guide to Their Organization and Terminology, Toronoto, 1982.

Huglo, M. Les livres de chant liturgiques, Turnhout, 1988.

McKitterick, David. Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450-1830, Cambridge, 2004.

Pächt, Otto, Dagmar Thoss. Die illuminierten Handschriften und Inkunabeln der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. Bd. 1: Französische Schule, Vienna, 1974.

Rudy, Kathryn M. Image, Knife, and Gluepot: Early Assemblage in Manuscript and Print, Cambridge, 2019.

https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/806

Rudy, Kathryn M. Postcards on Parchment: the Social Lives of Medieval Books, New Haven, 2015.

Schmidt, Peter. Gedruckte Bilder in handgeschriebenen Büchern: zum Gebrauch von Druckgraphik im 15. Jahrhundert, Cologne, 2003.

Smith, Innocent. ”Liturgy: Christianity: Roman Catholic Liturgy,” Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception, Berlin, 2009- , vol. 16 (2018), col. 921-926.

Plummer, John. The Last Flowering: French Painting in Manuscripts, 1420-1530: from American Collections, New York, 1982.

ONLINE RESOURCES

Cabrol, F. “Breviary,” in The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York, 1907. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02768b.htm

Lyon, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 5125, in “Initiale: Catalogue des manuscrits enluminés”

https://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/en/codex/2547

Philippa of Guelders (1467-1547)

https://thefreelancehistorywriter.com/2012/09/16/philippa-of-guelders-duchess-of-lorraine/

IIM 50444