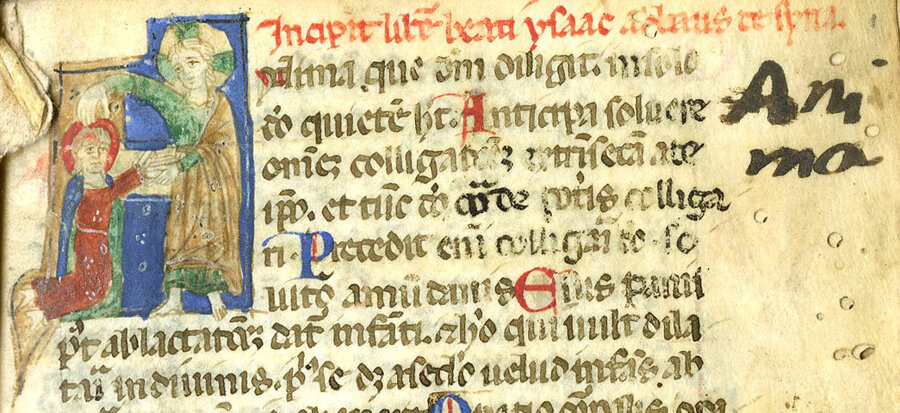

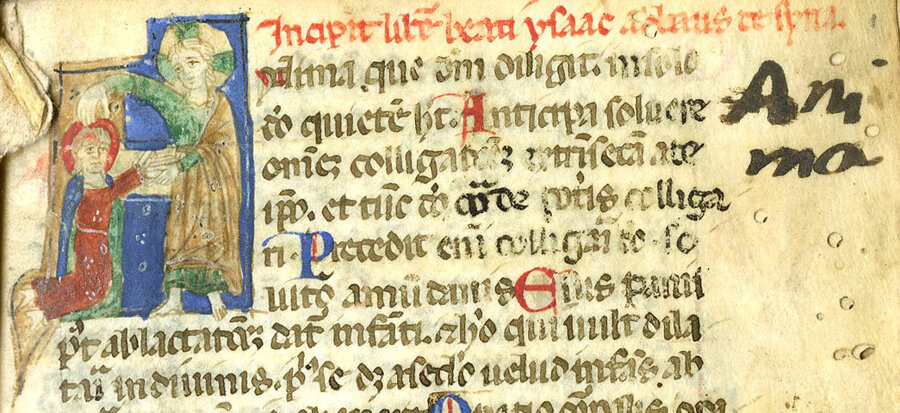

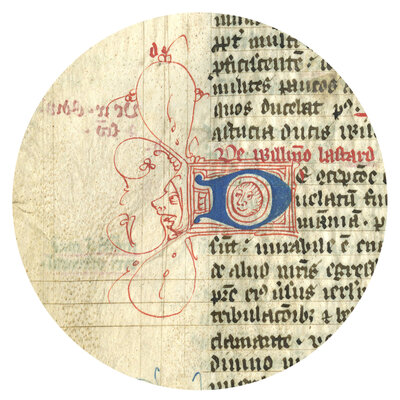

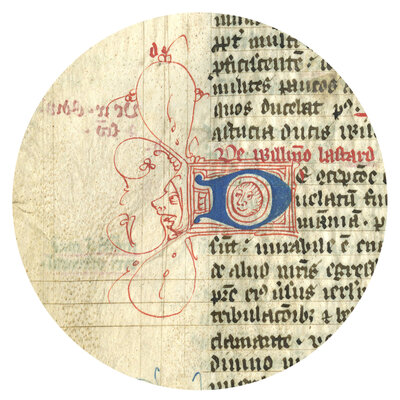

This historiated initial depicts author Isaac of Nineveh presenting his Liber de contemptu mundi to Christ. The initial opens the same text in a Franciscan miscellany, TM 675, f. 1 (detail), Northern Italy, c. 1260-1280 and c. 1280-1300

This historiated initial depicts author Isaac of Nineveh presenting his Liber de contemptu mundi to Christ. The initial opens the same text in a Franciscan miscellany, TM 675, f. 1 (detail), Northern Italy, c. 1260-1280 and c. 1280-1300

We all know that it is a pleasure to look through the pages of a decorated manuscript. It is especially exciting when the book looks back!

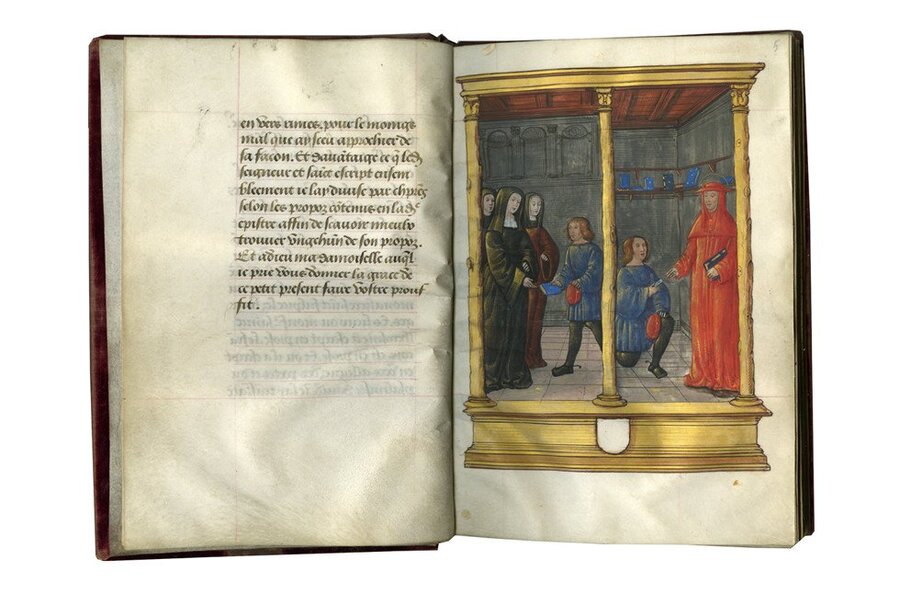

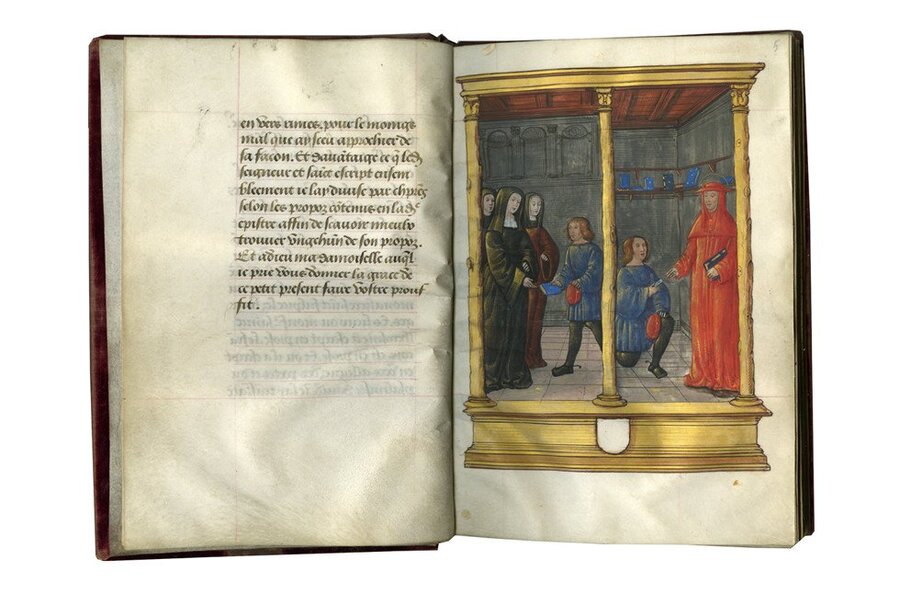

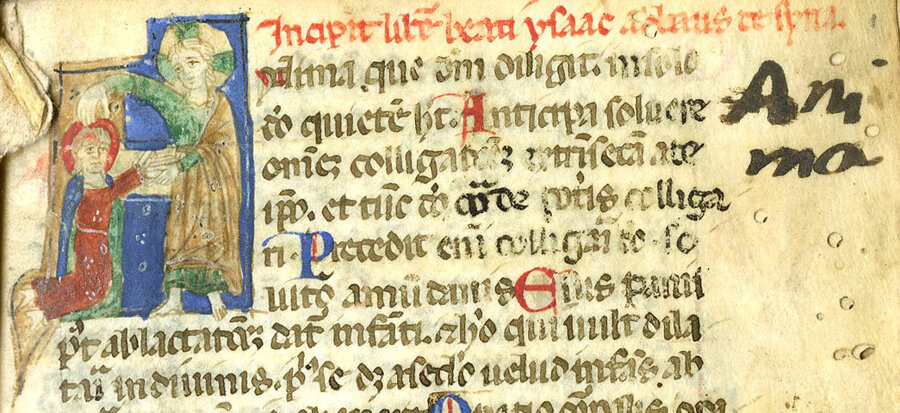

Miniatures can become windows into vivid moments of human action and interaction.

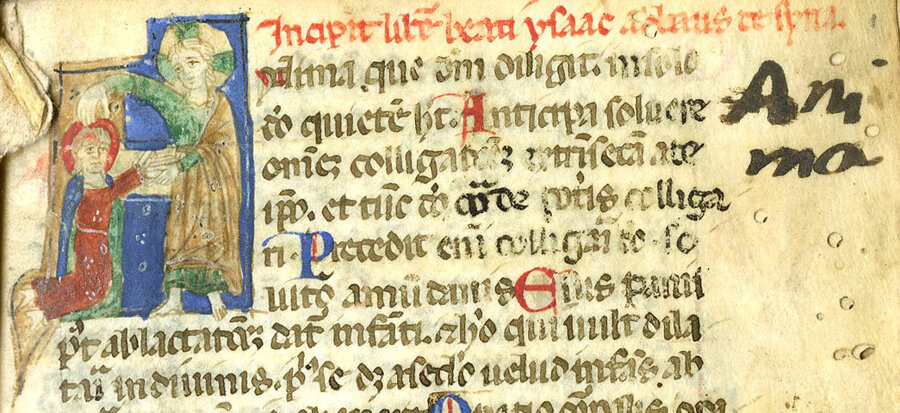

Saint Jerome (far right) gives an epistle to a messenger, who is also depicted handing it to Furia (far left), its intended recipient, in this elegant frontispiece, painted by the Master of Spencer 6, in this deluxe copy of Jerome’s Letter LIV to Furia, in the French translation of Charles Bonin, f. 5, France, likely Bourges, c. 1500-1510

Saint Jerome (far right) gives an epistle to a messenger, who is also depicted handing it to Furia (far left), its intended recipient, in this elegant frontispiece, painted by the Master of Spencer 6, in this deluxe copy of Jerome’s Letter LIV to Furia, in the French translation of Charles Bonin, f. 5, France, likely Bourges, c. 1500-1510

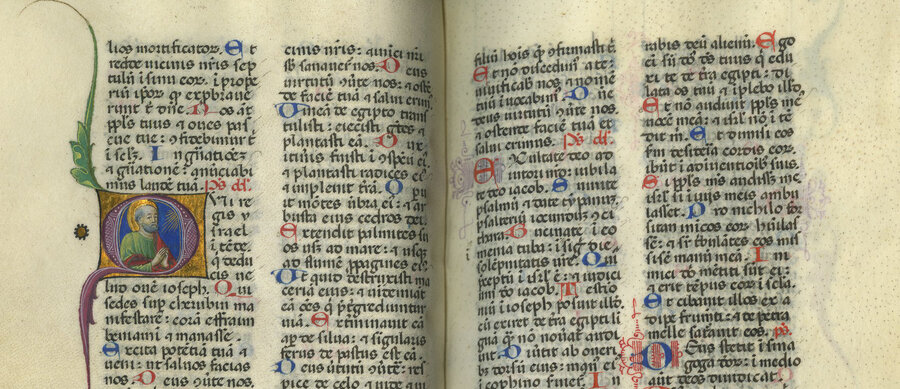

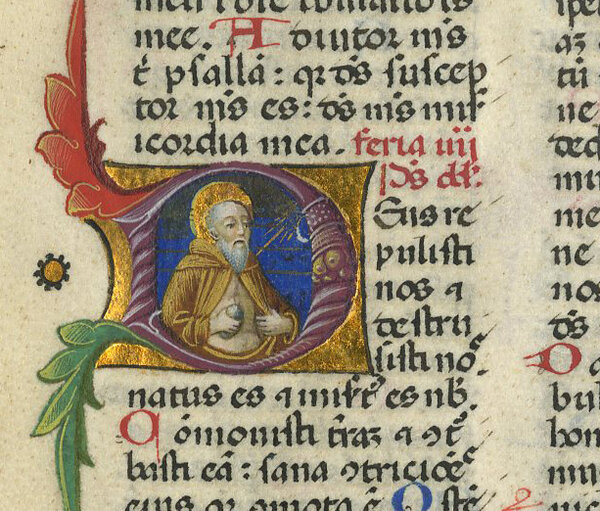

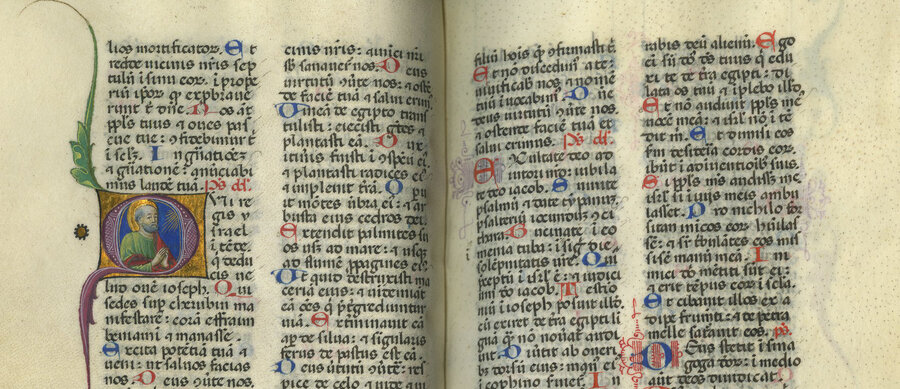

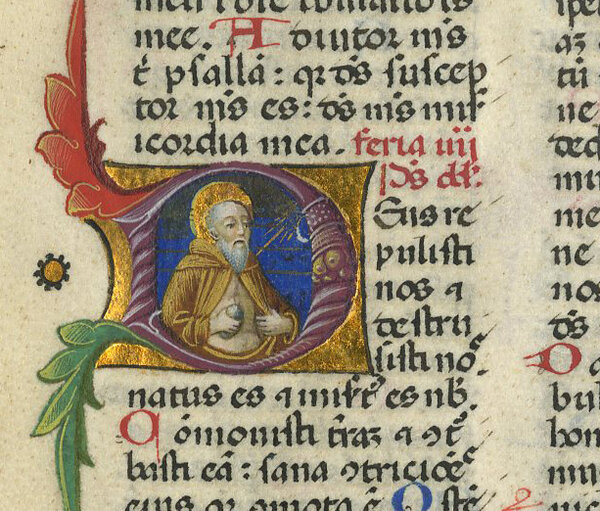

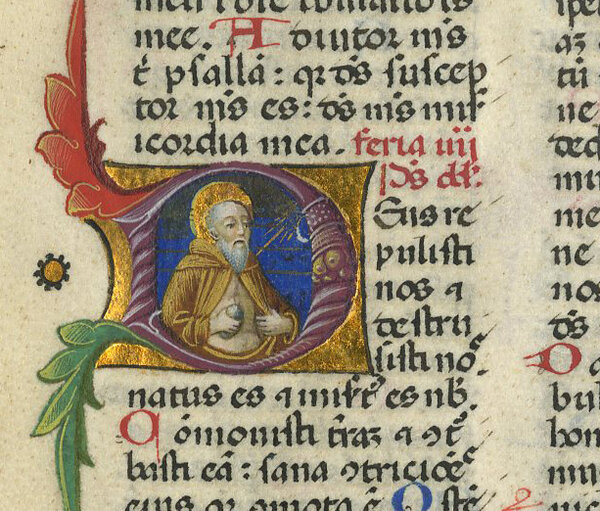

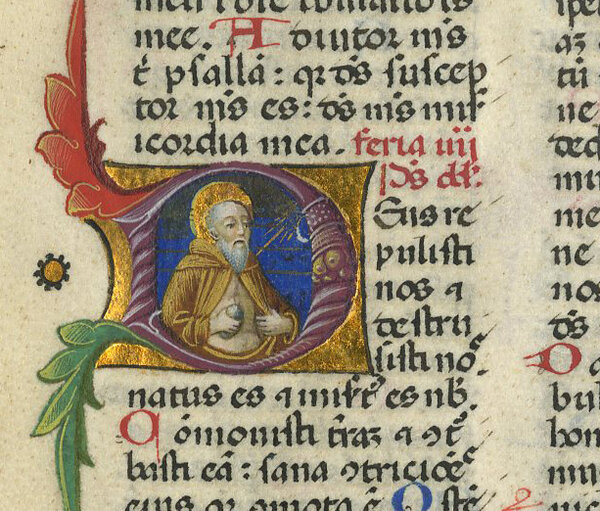

Painted initials on glimmering golden grounds frame saints at their devotions.

An unidentified saint clasps his hands in prayer in this historiated initial within an illuminated Carthusian Breviary, TM 815, f. 40v (detail), Northern Italy (Lombardy?), c. 1430-1450

An unidentified saint clasps his hands in prayer in this historiated initial within an illuminated Carthusian Breviary, TM 815, f. 40v (detail), Northern Italy (Lombardy?), c. 1430-1450

Illuminated figures like these complement the texts they accompany in ways we can understand, by putting us face to face with saintly intercessors in a book of prayer, or showing us the patrons (whether divine or human) of the very texts we are reading. Just as powerful, if often less comprehensible, are the human faces that peer out from the page in less expected places.

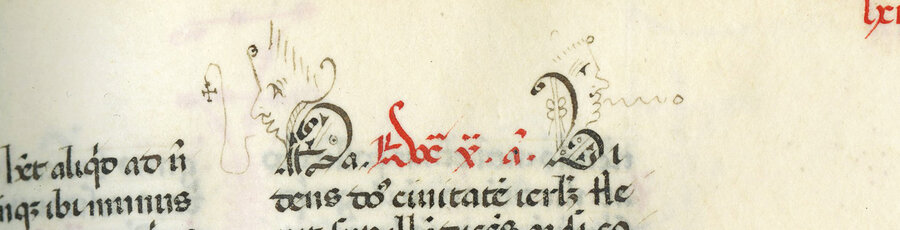

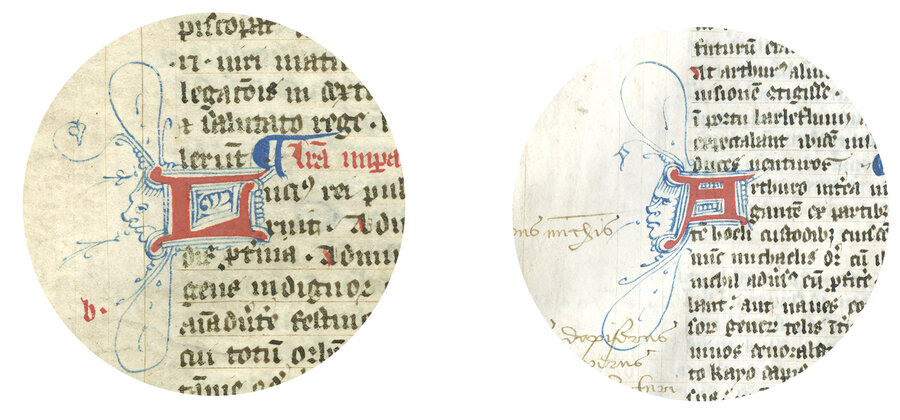

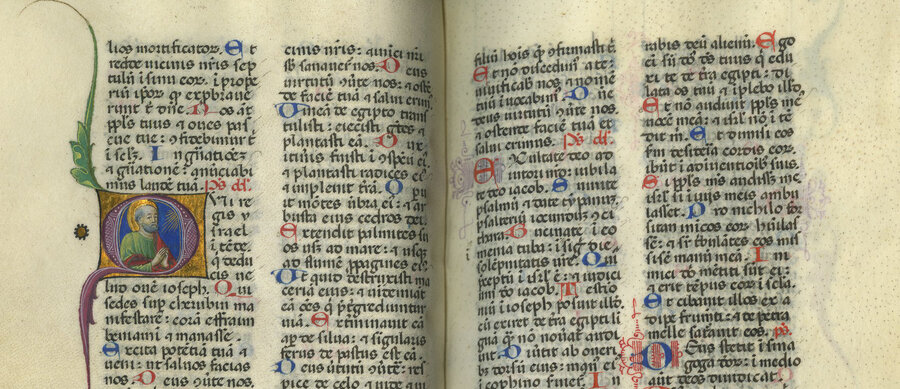

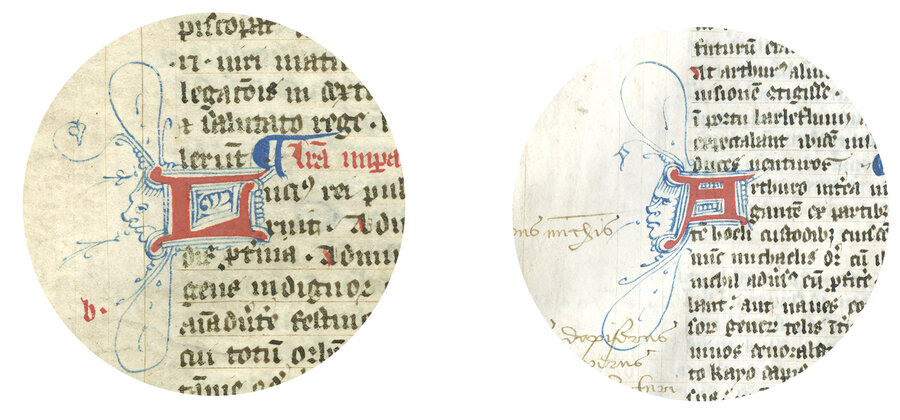

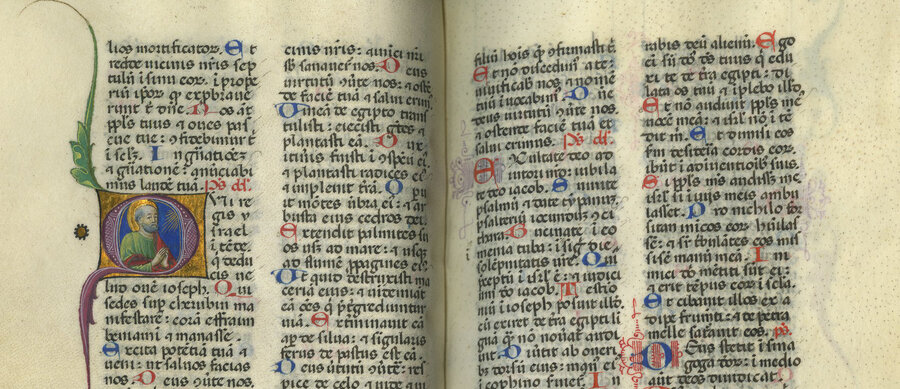

TM 815, ff. 169v-170

TM 815, ff. 169v-170

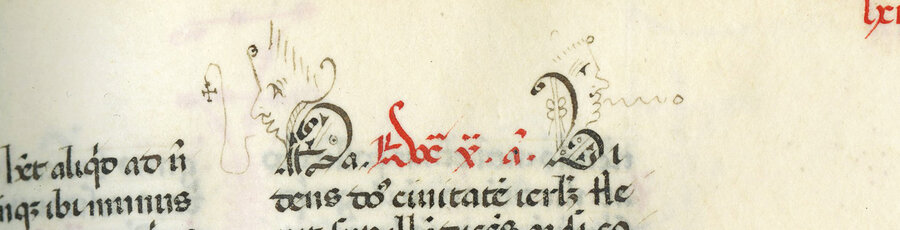

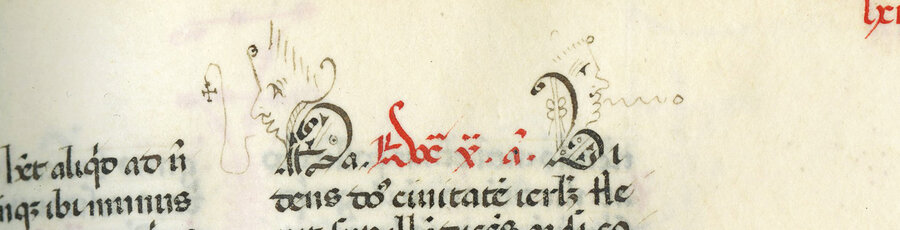

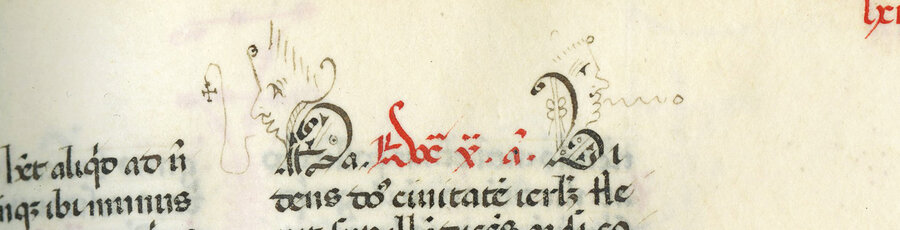

This fellow is part of the decorative flourishing on an initial whose placement on the page gave someone – probably the scribe? – the space to embellish a bit. He’s not alone either. Here, again, extra space in the upper margin has provided the pen flourisher with an irresistible playground.

Detail of TM 815, f.151

Detail of TM 815, f.151

There are many more of these. What’s more, these fanciful faces are all drawn in the same prayer book with the more traditional historiated initials shown earlier!

Saint Jerome beats his chest in penance in this detail of TM 815, f. 30v

Saint Jerome beats his chest in penance in this detail of TM 815, f. 30v

While the saints in initials like this one follow an established iconography though – we know we’re looking at a penitent Jerome here because he is clothed in a chest-baring robe and holding a stone with which to beat his breast – these flourished faces and their exhalations do not parse so easily. Are they blowing smoke rings? Speaking? Singing? In most cases the lines emanating from their mouths do end in crosses. Could it be that they are praying and that, for all of their strangeness, they represent the users of the prayerbook themselves?

This seems to be a possibility in another prayerbook, teeming with faces drawn by an adept pen flourisher:

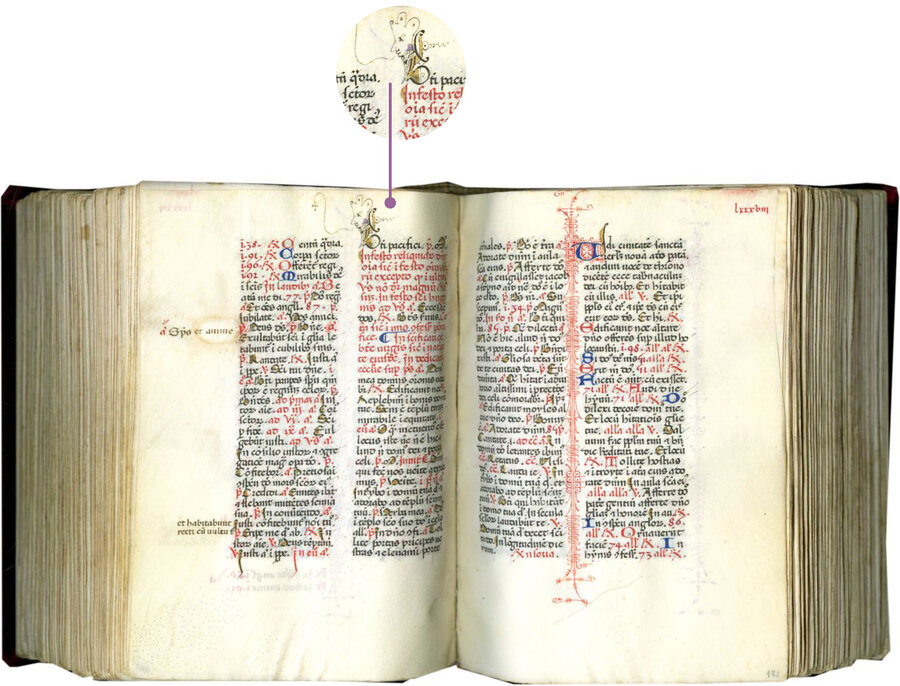

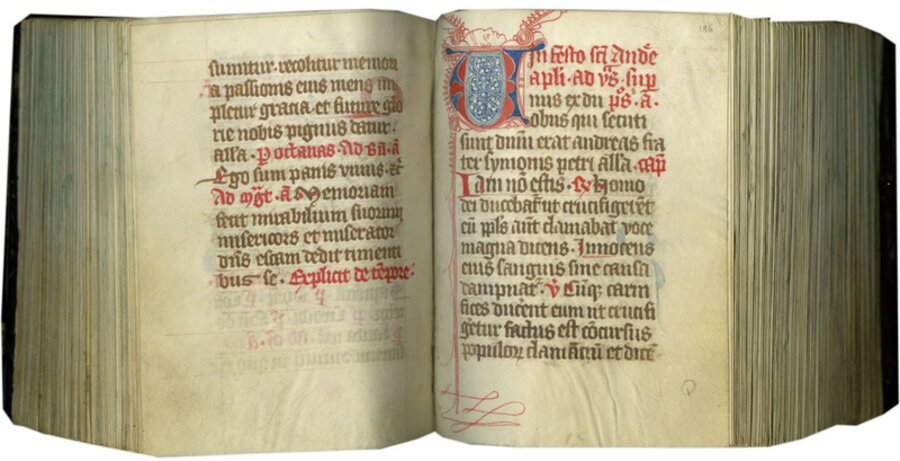

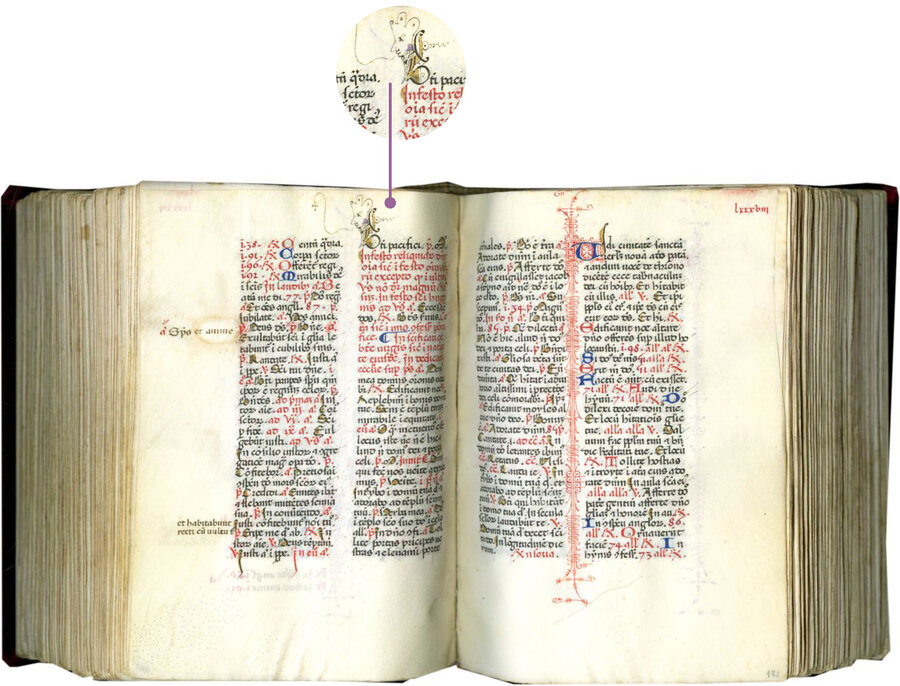

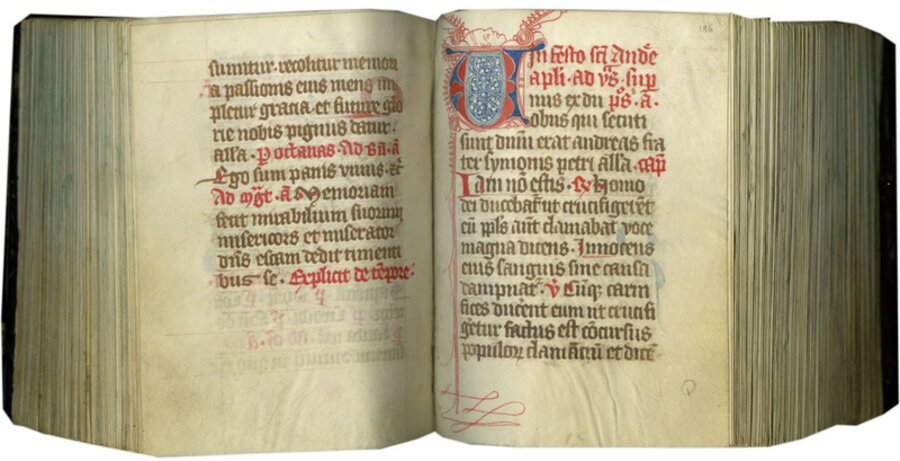

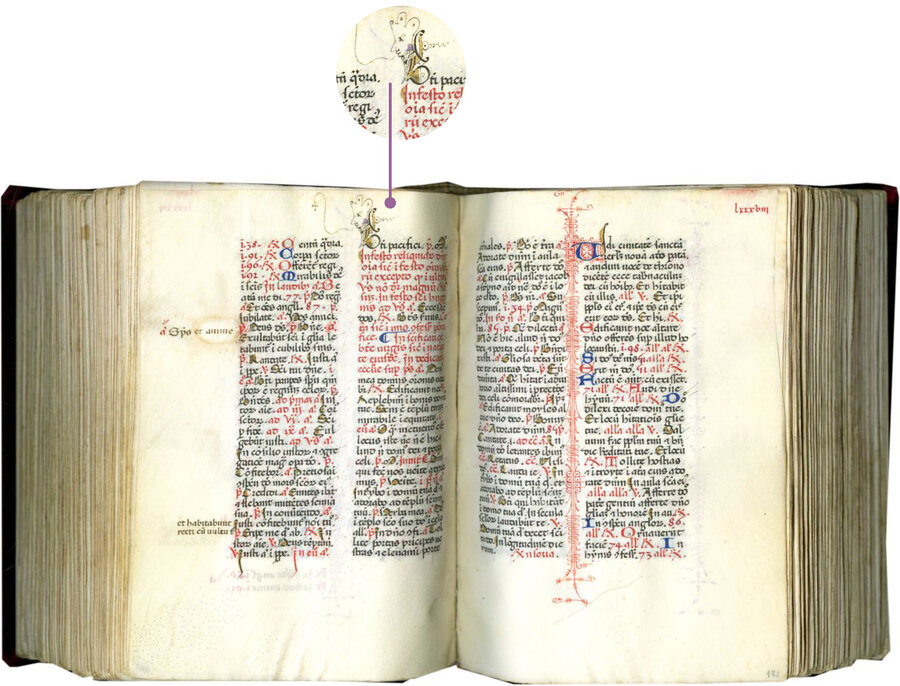

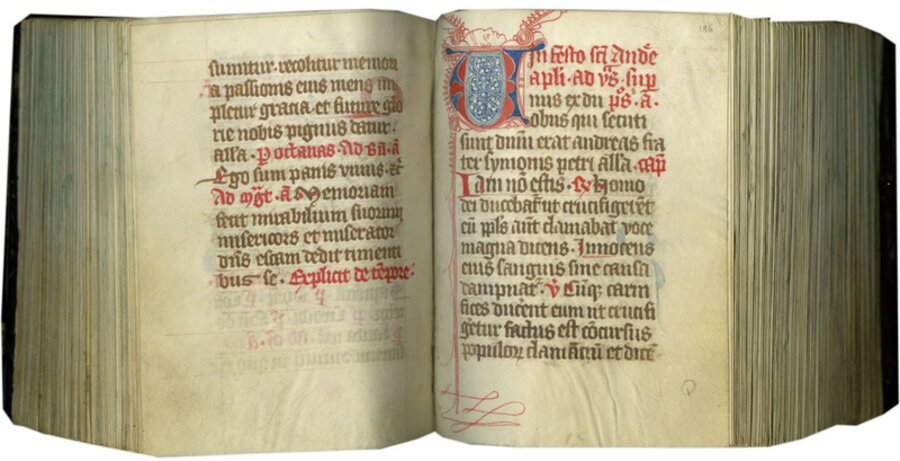

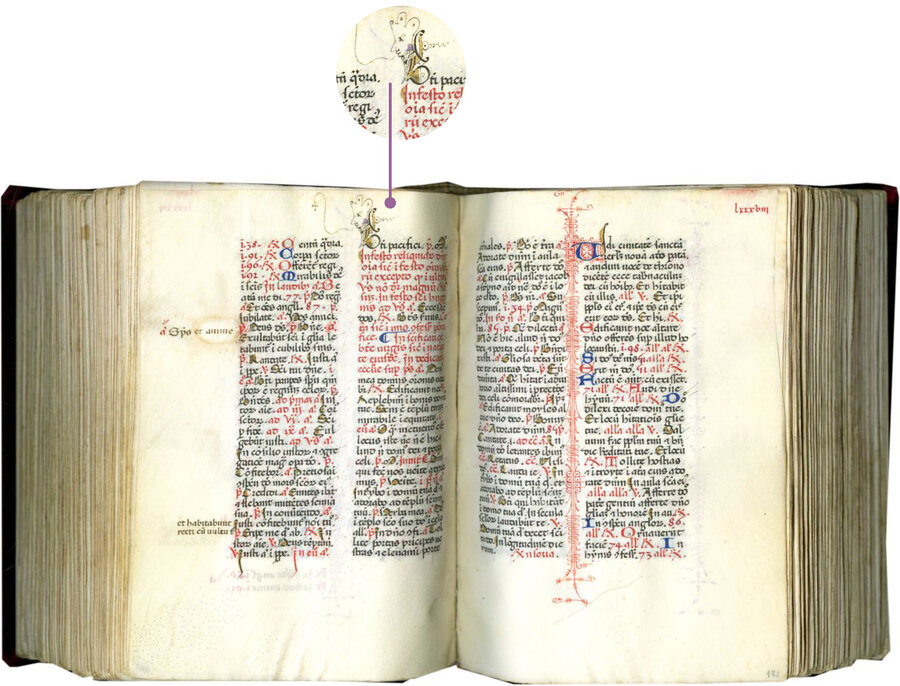

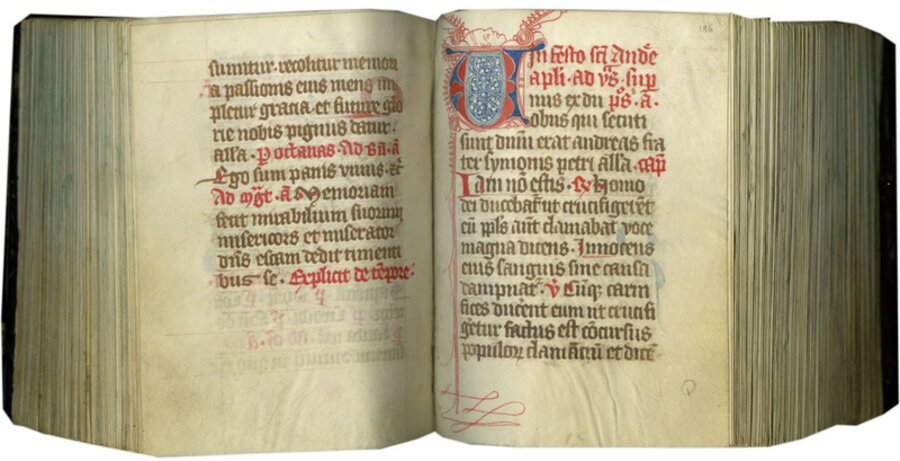

Dominican Breviary, TM 829, ff. 185v-186, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland), dated 1370, with fifteenth-century additions

Dominican Breviary, TM 829, ff. 185v-186, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland), dated 1370, with fifteenth-century additions

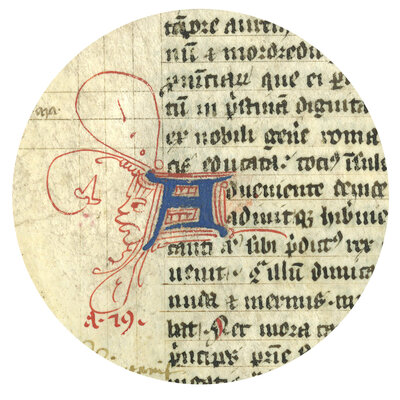

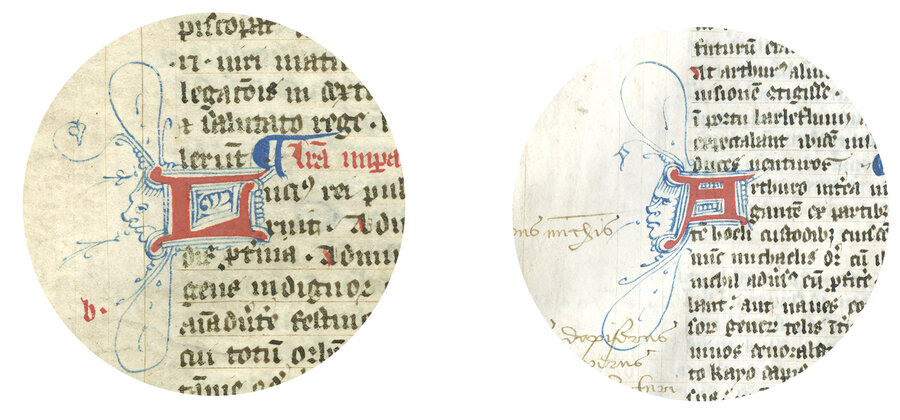

The tonsured face gazing upward atop this handsome initial could represent an imagined user of this finely decorated Breviary. And he’s not alone. Along with the dog-like creatures frisking in this Breviary’s initials, there is a veritable community of tonsured men facing – or sometimes even singing or shouting – out into the margins and gazing heavenward.

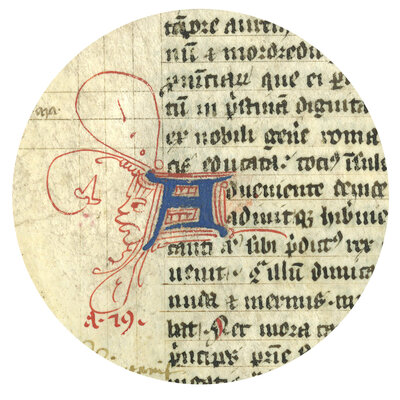

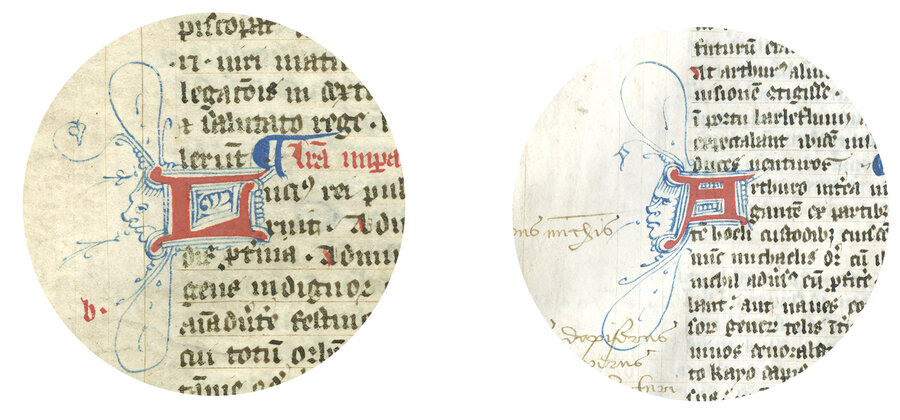

Details from TM 829, f. 233v; f. 226v

Details from TM 829, f. 233v; f. 226v

What stands out even more in these flourished faces, though, is the artist’s evident interest in capturing a range of features and expressions. Curled lips, wry smiles, and crooked noses are the products of his or her own delight in the work.

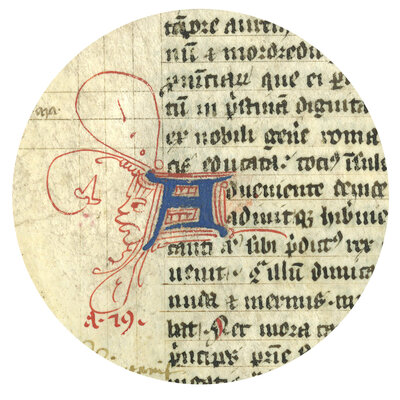

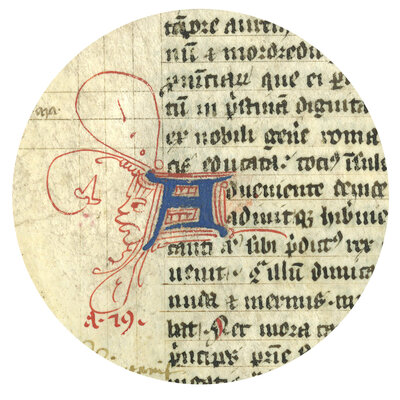

A similar relish is on display in this English manuscript:

Entranced by the pen decoration curling

Entranced by the pen decoration curling

This historiated initial depicts author Isaac of Nineveh presenting his Liber de contemptu mundi to Christ. The initial opens the same text in a Franciscan miscellany, TM 675, f. 1 (detail), Northern Italy, c. 1260-1280 and c. 1280-1300

This historiated initial depicts author Isaac of Nineveh presenting his Liber de contemptu mundi to Christ. The initial opens the same text in a Franciscan miscellany, TM 675, f. 1 (detail), Northern Italy, c. 1260-1280 and c. 1280-1300

We all know that it is a pleasure to look through the pages of a decorated manuscript. It is especially exciting when the book looks back!

Miniatures can become windows into vivid moments of human action and interaction.

Saint Jerome (far right) gives an epistle to a messenger, who is also depicted handing it to Furia (far left), its intended recipient, in this elegant frontispiece, painted by the Master of Spencer 6, in this deluxe copy of Jerome’s Letter LIV to Furia, in the French translation of Charles Bonin, f. 5, France, likely Bourges, c. 1500-1510

Saint Jerome (far right) gives an epistle to a messenger, who is also depicted handing it to Furia (far left), its intended recipient, in this elegant frontispiece, painted by the Master of Spencer 6, in this deluxe copy of Jerome’s Letter LIV to Furia, in the French translation of Charles Bonin, f. 5, France, likely Bourges, c. 1500-1510

Painted initials on glimmering golden grounds frame saints at their devotions.

An unidentified saint clasps his hands in prayer in this historiated initial within an illuminated Carthusian Breviary, TM 815, f. 40v (detail), Northern Italy (Lombardy?), c. 1430-1450

An unidentified saint clasps his hands in prayer in this historiated initial within an illuminated Carthusian Breviary, TM 815, f. 40v (detail), Northern Italy (Lombardy?), c. 1430-1450

Illuminated figures like these complement the texts they accompany in ways we can understand, by putting us face to face with saintly intercessors in a book of prayer, or showing us the patrons (whether divine or human) of the very texts we are reading. Just as powerful, if often less comprehensible, are the human faces that peer out from the page in less expected places.

TM 815, ff. 169v-170

TM 815, ff. 169v-170

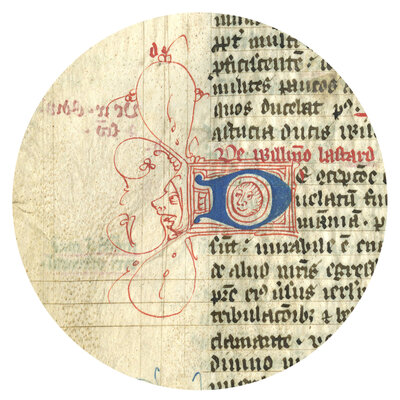

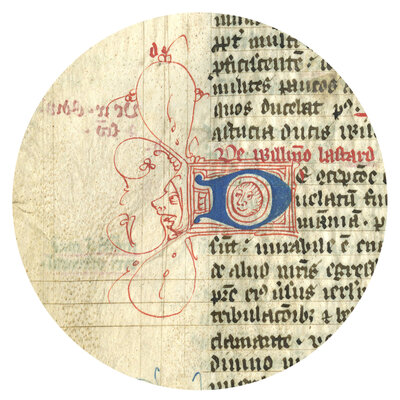

This fellow is part of the decorative flourishing on an initial whose placement on the page gave someone – probably the scribe? – the space to embellish a bit. He’s not alone either. Here, again, extra space in the upper margin has provided the pen flourisher with an irresistible playground.

Detail of TM 815, f.151

Detail of TM 815, f.151

There are many more of these. What’s more, these fanciful faces are all drawn in the same prayer book with the more traditional historiated initials shown earlier!

Saint Jerome beats his chest in penance in this detail of TM 815, f. 30v

Saint Jerome beats his chest in penance in this detail of TM 815, f. 30v

While the saints in initials like this one follow an established iconography though – we know we’re looking at a penitent Jerome here because he is clothed in a chest-baring robe and holding a stone with which to beat his breast – these flourished faces and their exhalations do not parse so easily. Are they blowing smoke rings? Speaking? Singing? In most cases the lines emanating from their mouths do end in crosses. Could it be that they are praying and that, for all of their strangeness, they represent the users of the prayerbook themselves?

This seems to be a possibility in another prayerbook, teeming with faces drawn by an adept pen flourisher:

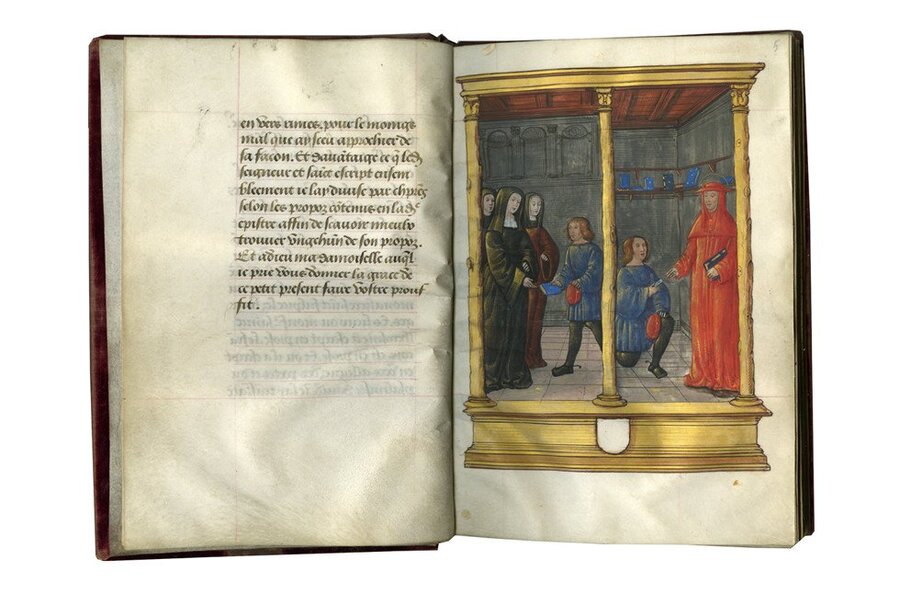

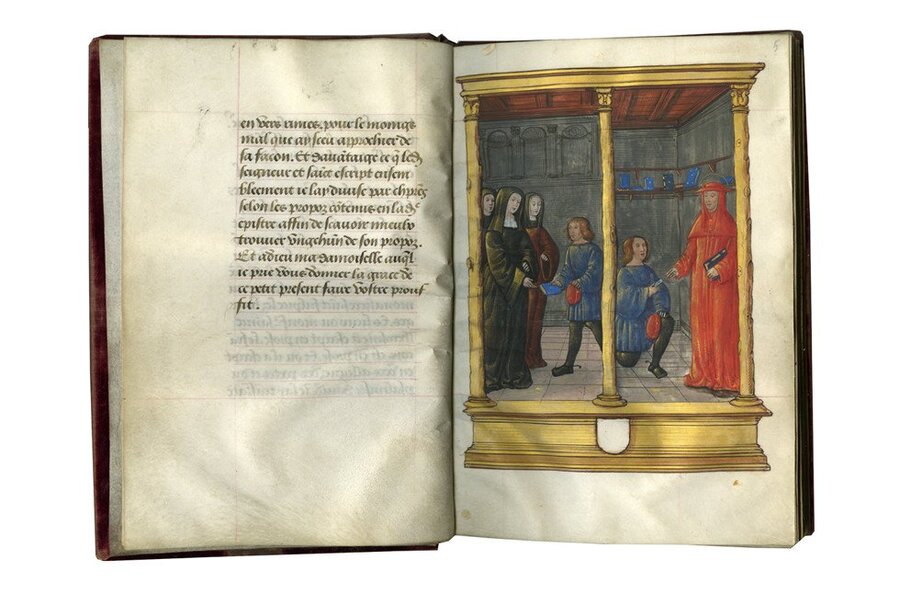

Dominican Breviary, TM 829, ff. 185v-186, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland), dated 1370, with fifteenth-century additions

Dominican Breviary, TM 829, ff. 185v-186, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland), dated 1370, with fifteenth-century additions

The tonsured face gazing upward atop this handsome initial could represent an imagined user of this finely decorated Breviary. And he’s not alone. Along with the dog-like creatures frisking in this Breviary’s initials, there is a veritable community of tonsured men facing – or sometimes even singing or shouting – out into the margins and gazing heavenward.

Details from TM 829, f. 233v; f. 226v

Details from TM 829, f. 233v; f. 226v

What stands out even more in these flourished faces, though, is the artist’s evident interest in capturing a range of features and expressions. Curled lips, wry smiles, and crooked noses are the products of his or her own delight in the work.

A similar relish is on display in this English manuscript:

Entranced by the pen decoration curling overhead, this face adorns an initial in a chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, f. 20v (detail), England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

Entranced by the pen decoration curling overhead, this face adorns an initial in a chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, f. 20v (detail), England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

As in the Breviary just above, merely decorative pen flourishings periodically give way to lively faces peering out into the margins. They’re fascinatingly variable – and inexplicable – but most of all they are vividly expressive.

You can practically see this pen-drawing sigh in weary resignation, TM 836, f. 23v (detail); and this one rolls his eyes in evident exasperation, TM 836, f. 25v (detail)

A sufferer from leaf and mouth disease?, TM 836, f. 44v (detail)

As if these weren’t enough, there’s much more happening in the margins of this wonderful book. Check back soon for an upcoming post on the dead men in the manuscript’s margins!

This historiated initial depicts author Isaac of Nineveh presenting his Liber de contemptu mundi to Christ. The initial opens the same text in a Franciscan miscellany, TM 675, f. 1 (detail), Northern Italy, c. 1260-1280 and c. 1280-1300

This historiated initial depicts author Isaac of Nineveh presenting his Liber de contemptu mundi to Christ. The initial opens the same text in a Franciscan miscellany, TM 675, f. 1 (detail), Northern Italy, c. 1260-1280 and c. 1280-1300

We all know that it is a pleasure to look through the pages of a decorated manuscript. It is especially exciting when the book looks back!

Miniatures can become windows into vivid moments of human action and interaction.

Saint Jerome (far right) gives an epistle to a messenger, who is also depicted handing it to Furia (far left), its intended recipient, in this elegant frontispiece, painted by the Master of Spencer 6, in this deluxe copy of Jerome’s Letter LIV to Furia, in the French translation of Charles Bonin, f. 5, France, likely Bourges, c. 1500-1510

Saint Jerome (far right) gives an epistle to a messenger, who is also depicted handing it to Furia (far left), its intended recipient, in this elegant frontispiece, painted by the Master of Spencer 6, in this deluxe copy of Jerome’s Letter LIV to Furia, in the French translation of Charles Bonin, f. 5, France, likely Bourges, c. 1500-1510

Painted initials on glimmering golden grounds frame saints at their devotions.

An unidentified saint clasps his hands in prayer in this historiated initial within an illuminated Carthusian Breviary, TM 815, f. 40v (detail), Northern Italy (Lombardy?), c. 1430-1450

An unidentified saint clasps his hands in prayer in this historiated initial within an illuminated Carthusian Breviary, TM 815, f. 40v (detail), Northern Italy (Lombardy?), c. 1430-1450

Illuminated figures like these complement the texts they accompany in ways we can understand, by putting us face to face with saintly intercessors in a book of prayer, or showing us the patrons (whether divine or human) of the very texts we are reading. Just as powerful, if often less comprehensible, are the human faces that peer out from the page in less expected places.

TM 815, ff. 169v-170

TM 815, ff. 169v-170

This fellow is part of the decorative flourishing on an initial whose placement on the page gave someone – probably the scribe? – the space to embellish a bit. He’s not alone either. Here, again, extra space in the upper margin has provided the pen flourisher with an irresistible playground.

Detail of TM 815, f.151

Detail of TM 815, f.151

There are many more of these. What’s more, these fanciful faces are all drawn in the same prayer book with the more traditional historiated initials shown earlier!

Saint Jerome beats his chest in penance in this detail of TM 815, f. 30v

Saint Jerome beats his chest in penance in this detail of TM 815, f. 30v

While the saints in initials like this one follow an established iconography though – we know we’re looking at a penitent Jerome here because he is clothed in a chest-baring robe and holding a stone with which to beat his breast – these flourished faces and their exhalations do not parse so easily. Are they blowing smoke rings? Speaking? Singing? In most cases the lines emanating from their mouths do end in crosses. Could it be that they are praying and that, for all of their strangeness, they represent the users of the prayerbook themselves?

This seems to be a possibility in another prayerbook, teeming with faces drawn by an adept pen flourisher:

Dominican Breviary, TM 829, ff. 185v-186, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland), dated 1370, with fifteenth-century additions

Dominican Breviary, TM 829, ff. 185v-186, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland), dated 1370, with fifteenth-century additions

The tonsured face gazing upward atop this handsome initial could represent an imagined user of this finely decorated Breviary. And he’s not alone. Along with the dog-like creatures frisking in this Breviary’s initials, there is a veritable community of tonsured men facing – or sometimes even singing or shouting – out into the margins and gazing heavenward.

Details from TM 829, f. 233v; f. 226v

Details from TM 829, f. 233v; f. 226v

What stands out even more in these flourished faces, though, is the artist’s evident interest in capturing a range of features and expressions. Curled lips, wry smiles, and crooked noses are the products of his or her own delight in the work.

A similar relish is on display in this English manuscript:

Entranced by the pen decoration curling overhead, this face adorns an initial in a chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, f. 20v (detail), England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

Entranced by the pen decoration curling overhead, this face adorns an initial in a chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, f. 20v (detail), England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

As in the Breviary just above, merely decorative pen flourishings periodically give way to lively faces peering out into the margins. They’re fascinatingly variable – and inexplicable – but most of all they are vividly expressive.

You can practically see this pen-drawing sigh in weary resignation, TM 836, f. 23v (detail); and this one rolls his eyes in evident exasperation, TM 836, f. 25v (detail)

A sufferer from leaf and mouth disease?, TM 836, f. 44v (detail)

As if these weren’t enough, there’s much more happening in the margins of this wonderful book. Check back soon for an upcoming post on the dead men in the manuscript’s margins!

overhead, this face adorns an initial in a chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, f. 20v (detail), England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

As in the Breviary just above, merely decorative pen flourishings periodically give way to lively faces peering out into the margins. They’re fascinatingly variable – and inexplicable – but most of all they are vividly expressive.

You can practically see this pen-drawing sigh in weary resignation, TM 836, f. 23v (detail); and this one rolls his eyes in evident exasperation, TM 836, f. 25v (detail)

A sufferer from leaf and mouth disease?, TM 836, f. 44v (detail)

As if these weren’t enough, there’s much more happening in the margins of this wonderful book. Check back soon for an upcoming post on the dead men in the manuscript’s margins!

This historiated initial depicts author Isaac of Nineveh presenting his Liber de contemptu mundi to Christ. The initial opens the same text in a Franciscan miscellany, TM 675, f. 1 (detail), Northern Italy, c. 1260-1280 and c. 1280-1300

This historiated initial depicts author Isaac of Nineveh presenting his Liber de contemptu mundi to Christ. The initial opens the same text in a Franciscan miscellany, TM 675, f. 1 (detail), Northern Italy, c. 1260-1280 and c. 1280-1300

We all know that it is a pleasure to look through the pages of a decorated manuscript. It is especially exciting when the book looks back!

Miniatures can become windows into vivid moments of human action and interaction.

Saint Jerome (far right) gives an epistle to a messenger, who is also depicted handing it to Furia (far left), its intended recipient, in this elegant frontispiece, painted by the Master of Spencer 6, in this deluxe copy of Jerome’s Letter LIV to Furia, in the French translation of Charles Bonin, f. 5, France, likely Bourges, c. 1500-1510

Saint Jerome (far right) gives an epistle to a messenger, who is also depicted handing it to Furia (far left), its intended recipient, in this elegant frontispiece, painted by the Master of Spencer 6, in this deluxe copy of Jerome’s Letter LIV to Furia, in the French translation of Charles Bonin, f. 5, France, likely Bourges, c. 1500-1510

Painted initials on glimmering golden grounds frame saints at their devotions.

An unidentified saint clasps his hands in prayer in this historiated initial within an illuminated Carthusian Breviary, TM 815, f. 40v (detail), Northern Italy (Lombardy?), c. 1430-1450

An unidentified saint clasps his hands in prayer in this historiated initial within an illuminated Carthusian Breviary, TM 815, f. 40v (detail), Northern Italy (Lombardy?), c. 1430-1450

Illuminated figures like these complement the texts they accompany in ways we can understand, by putting us face to face with saintly intercessors in a book of prayer, or showing us the patrons (whether divine or human) of the very texts we are reading. Just as powerful, if often less comprehensible, are the human faces that peer out from the page in less expected places.

TM 815, ff. 169v-170

TM 815, ff. 169v-170

This fellow is part of the decorative flourishing on an initial whose placement on the page gave someone – probably the scribe? – the space to embellish a bit. He’s not alone either. Here, again, extra space in the upper margin has provided the pen flourisher with an irresistible playground.

Detail of TM 815, f.151

Detail of TM 815, f.151

There are many more of these. What’s more, these fanciful faces are all drawn in the same prayer book with the more traditional historiated initials shown earlier!

Saint Jerome beats his chest in penance in this detail of TM 815, f. 30v

Saint Jerome beats his chest in penance in this detail of TM 815, f. 30v

While the saints in initials like this one follow an established iconography though – we know we’re looking at a penitent Jerome here because he is clothed in a chest-baring robe and holding a stone with which to beat his breast – these flourished faces and their exhalations do not parse so easily. Are they blowing smoke rings? Speaking? Singing? In most cases the lines emanating from their mouths do end in crosses. Could it be that they are praying and that, for all of their strangeness, they represent the users of the prayerbook themselves?

This seems to be a possibility in another prayerbook, teeming with faces drawn by an adept pen flourisher:

Dominican Breviary, TM 829, ff. 185v-186, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland), dated 1370, with fifteenth-century additions

Dominican Breviary, TM 829, ff. 185v-186, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland), dated 1370, with fifteenth-century additions

The tonsured face gazing upward atop this handsome initial could represent an imagined user of this finely decorated Breviary. And he’s not alone. Along with the dog-like creatures frisking in this Breviary’s initials, there is a veritable community of tonsured men facing – or sometimes even singing or shouting – out into the margins and gazing heavenward.

Details from TM 829, f. 233v; f. 226v

Details from TM 829, f. 233v; f. 226v

What stands out even more in these flourished faces, though, is the artist’s evident interest in capturing a range of features and expressions. Curled lips, wry smiles, and crooked noses are the products of his or her own delight in the work.

A similar relish is on display in this English manuscript:

Entranced by the pen decoration curling overhead, this face adorns an initial in a chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, f. 20v (detail), England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

Entranced by the pen decoration curling overhead, this face adorns an initial in a chronicle of English history, the Eulogium historiarum, TM 836, f. 20v (detail), England (Malmesbury?), c. 1375-1400

As in the Breviary just above, merely decorative pen flourishings periodically give way to lively faces peering out into the margins. They’re fascinatingly variable – and inexplicable – but most of all they are vividly expressive.

You can practically see this pen-drawing sigh in weary resignation, TM 836, f. 23v (detail); and this one rolls his eyes in evident exasperation, TM 836, f. 25v (detail)

A sufferer from leaf and mouth disease?, TM 836, f. 44v (detail)

As if these weren’t enough, there’s much more happening in the margins of this wonderful book. Check back soon for an upcoming post on the dead men in the manuscript’s margins!