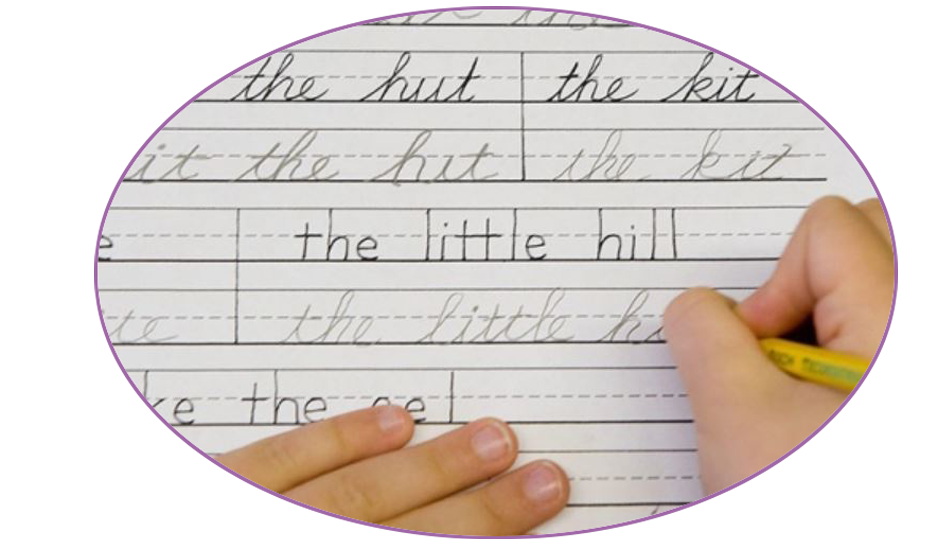

We usually steer clear of divisive political issues in this blog, but today we are going to plunge right in (no pun intended). Cursive handwriting, and how to teach it – or indeed, whether to teach it or not – is a hotly debated topic right now. Take a look at a recent article that appeared in the New York Times on April 13, 2019 by Emily S. Rube “Cursive Seemed to Go the Way of Quills and Parchment. Now It’s Coming Back.”

Do students, who we know will spend their life using a keyboard, need to learn how to write?

Teaching cursive script has even become part of the conservative agenda. Pam Roach, then a senator from Washington State, who sponsored an (unsuccessful) bill to mandate the teaching of cursive in schools, said in 2016, “Part of being an American is being able to read cursive handwriting.”

Well, it is a little difficult, at least for me, to understand the link between “being American” and reading cursive script, but it does seem to be an essential skill. Admittedly, my point of view as a medievalist, who spends my days studying hand-written manuscripts, may be a bit biased. (I would also agree with Ms. Roach that if you don’t learn how to write cursive, you will have trouble reading it. Although, as a paleographer, I will say that I can read many medieval scripts that I cannot write).

This debate got me thinking, how did people learn to write in the past?

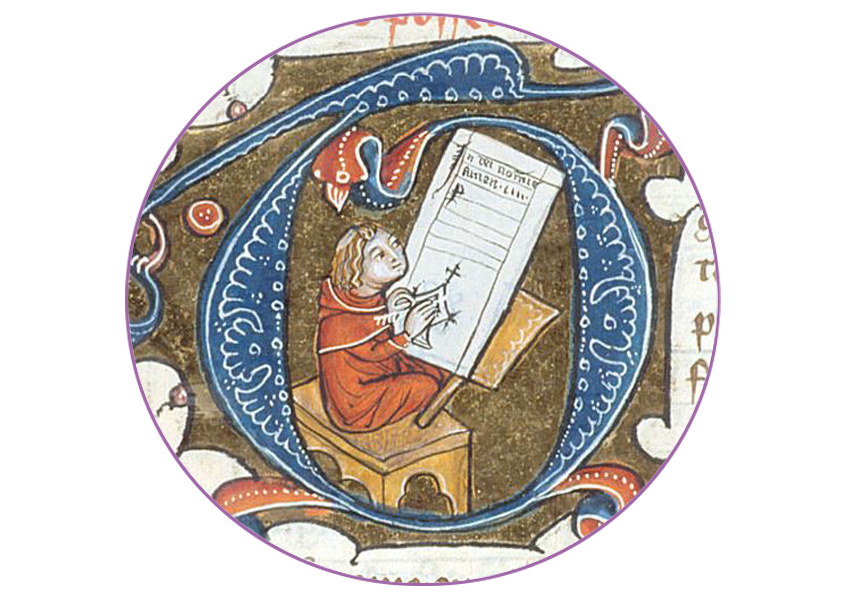

James le Palmer, Omne bonum, “Tabelliones” (notaries), London, British Library, MS Royal 6 E VII, f., London, c. 1300-1375

For most of the Middle Ages, the answer is we really don’t know. There is little direct evidence of how scribes learned how to write in the early Middle Ages. Writing a formal script used in copying books in a monastic scriptorium was a carefully acquired skill, and presumably was taught by skilled practitioners handing down the skill to novices.

Much of the art of writing was doubtless transmitted orally (as the miniature possibly depicts),

Is this a scribe demonstrating to his students the art of writing? Bartholomaeus Anglicus, tr. Jean Corbechon, Livre des proprietez des choses, London, British Library, MS Royal 7 E III, f. 209, Paris(?), c. 1500-1525.

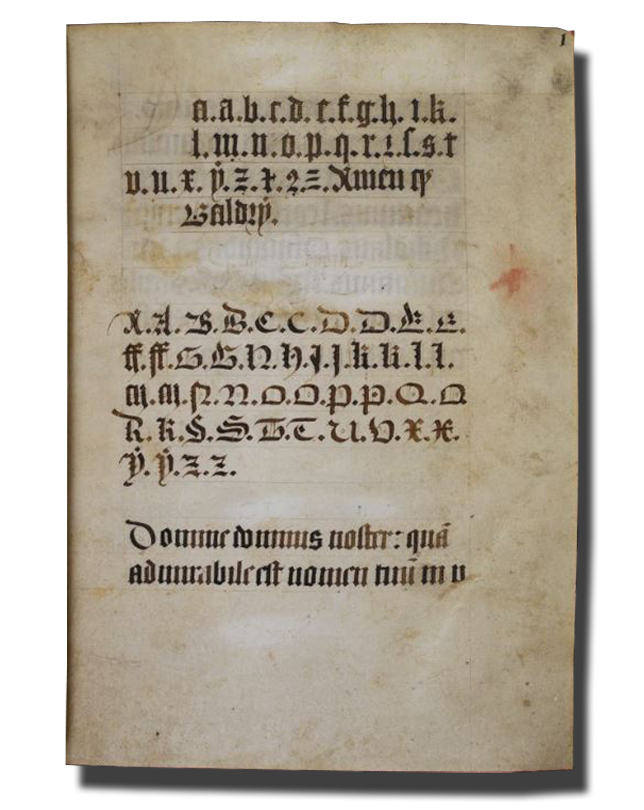

but model books also provided sample alphabets and decorated letters to copy. The earliest model book is from twelfth-century Italy, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 83-1972.*

*(Interested in model books? Read more about the topic in Erik Kwakkel’s blog, “Medieval Super Models”).

Most surviving examples, however, are later in date. The “Macclesfield alphabet book,” London, British Library, Additional MS 8887, is a famous English example, from c. 1475-1525, perhaps by Roger Baldry of the Cluniac priory of St Mary of Thetford, Norfolk (prior 1503-c. 1518).

The manuscript includes a straightforward alphabet,

London, British Library, Additional MS 8887, f. 1r

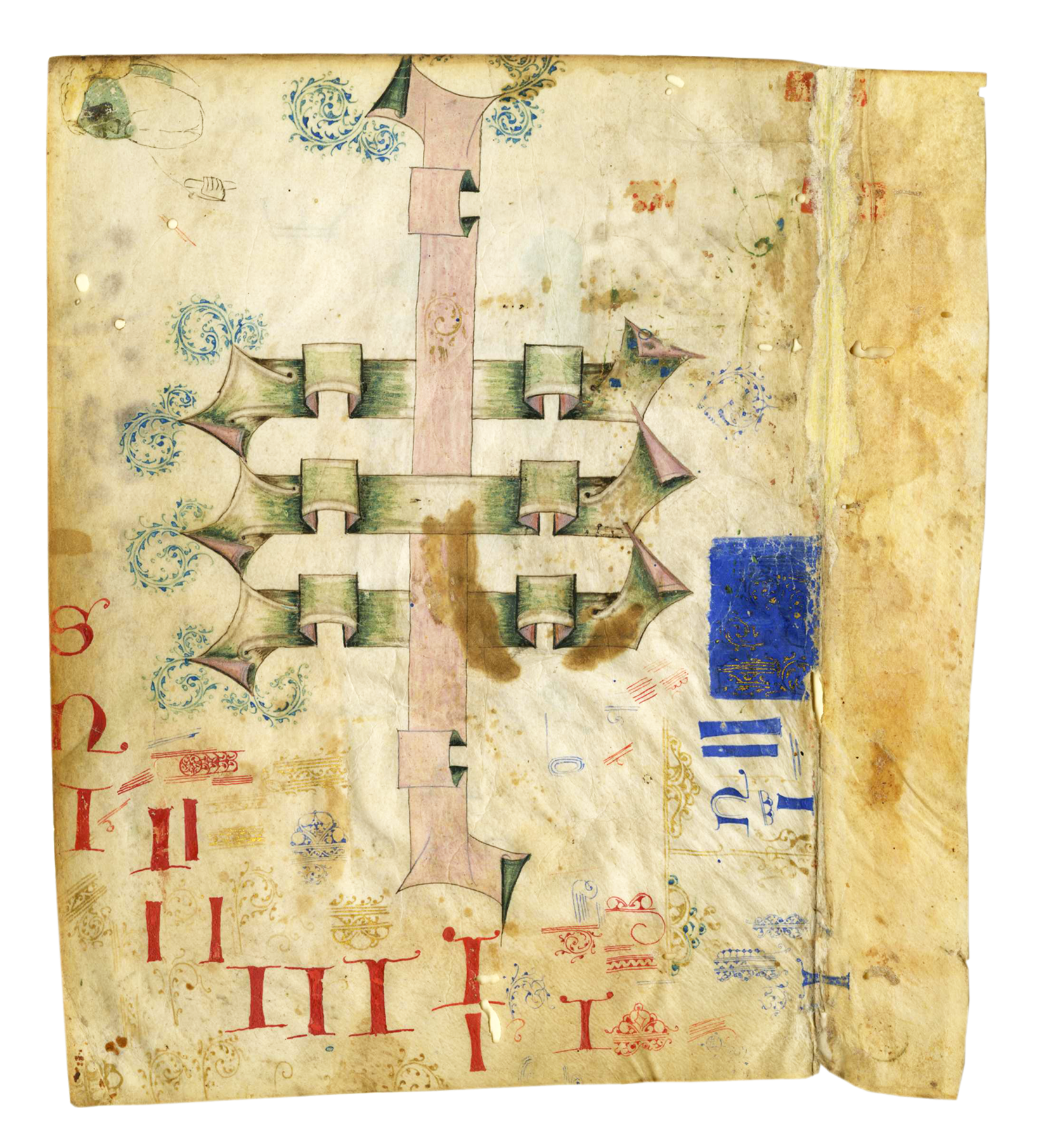

but it is celebrated for its fanciful decorated initials.

London, British Library, Additional MS 8887, f. 5r

Here we have a single sheet with a large pink and green lattice-work design made of components that could be used for letters, surrounded by added letters and pen-work motifs. This may be a page from an Italian model book for scribes and artists that was subsequently used as a practice sheet.

Les Enluminures, Leaf from a model book, Italy, c. 1400

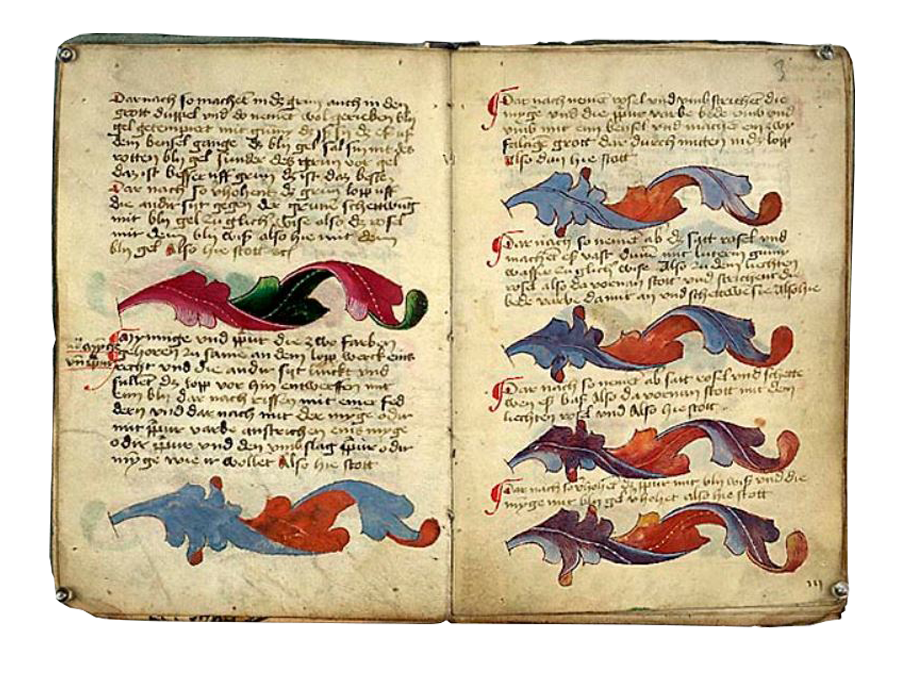

The Göttingen model book is an even more famous German example from the mid-fifteenth century, which explains through text and image how to mix pigments, and how to make several key decorative motifs. There are no alphabets in this book, so strictly speaking I shouldn’t mention it here, but I wanted to direct everyone to “Gutenberg digital,” edited by Elmar Mittler and Stephan Füssel, where you can page through the model book, read a translation of its text, and see the motifs used in a copy of the Gutenberg Bible.

Göttingen State and University Library, Göttingen model book ff. 2v-3

The Göttingen model book, with its connection to one copy of the Gutenberg Bible, the very first printed book, is a reminder that even after the invention of printing in the mid-fifteenth century, the ability to copy and decorate books and documents in a formal script continued to be a valued skill.

Göttingen State and University Library, Gutenberg Bible, vol. 1, f. 5.

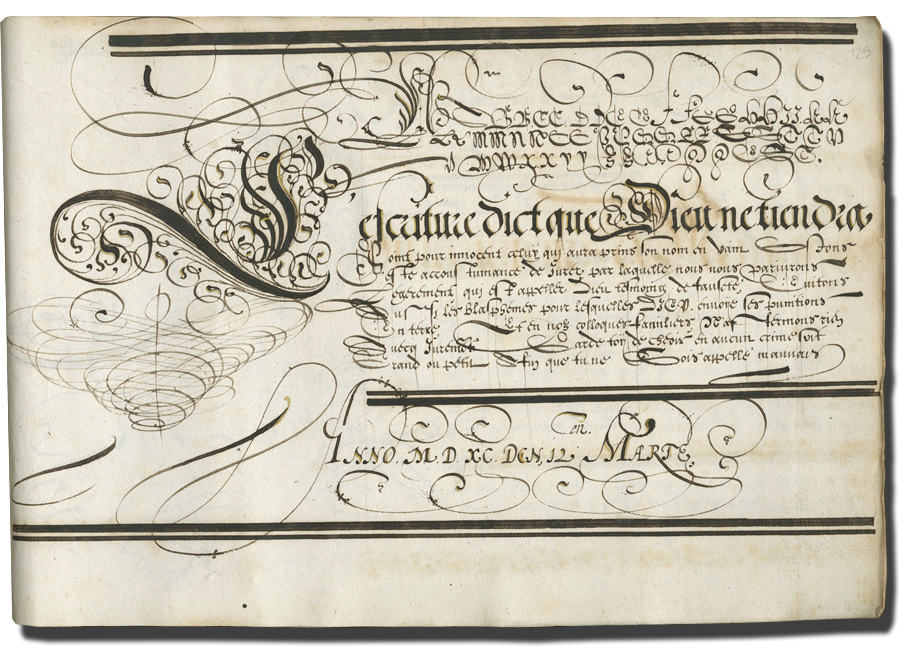

In the Middle Ages, handwriting (at least writing a formal script) was not part of elementary education; by the later Middle Ages we know it was taught by teachers who specialized in teaching writing. For example, by the fourteenth-century in Oxford professional “scriveners” who were not part of the University made a living by teaching formal handwriting as well as related legal skills, including how to draft charters. Writing was taught in a similar way in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Writing-masters taught both in person (often running schools in their homes) and by means of copy books and writing manuals that circulated as manuscripts and in the new medium of print. The earliest printed example is Italian, La Operina di Ludouico Vicentino, da imparare di scriuere littera cancellarescha (1522 or 1524) by Ludovico Vicentino degli Arrighi, who was employed in the Papal chancery.

In Germany, Johann Neudörffer (1497-1563) stands at the beginning of a long tradition of writing-masters and their manuals. His life was spent in Nuremberg teaching writing and arithmetic. His mathematical interests are highlighted in this portrait painted near the end of his life.

Germanischen Nationalmuseums, “Portrait of the Nuremberg Writing-master Johann Neudorffer and his Student,” by Nicolas Neufchâtel, Nuremberg, c. 1561.

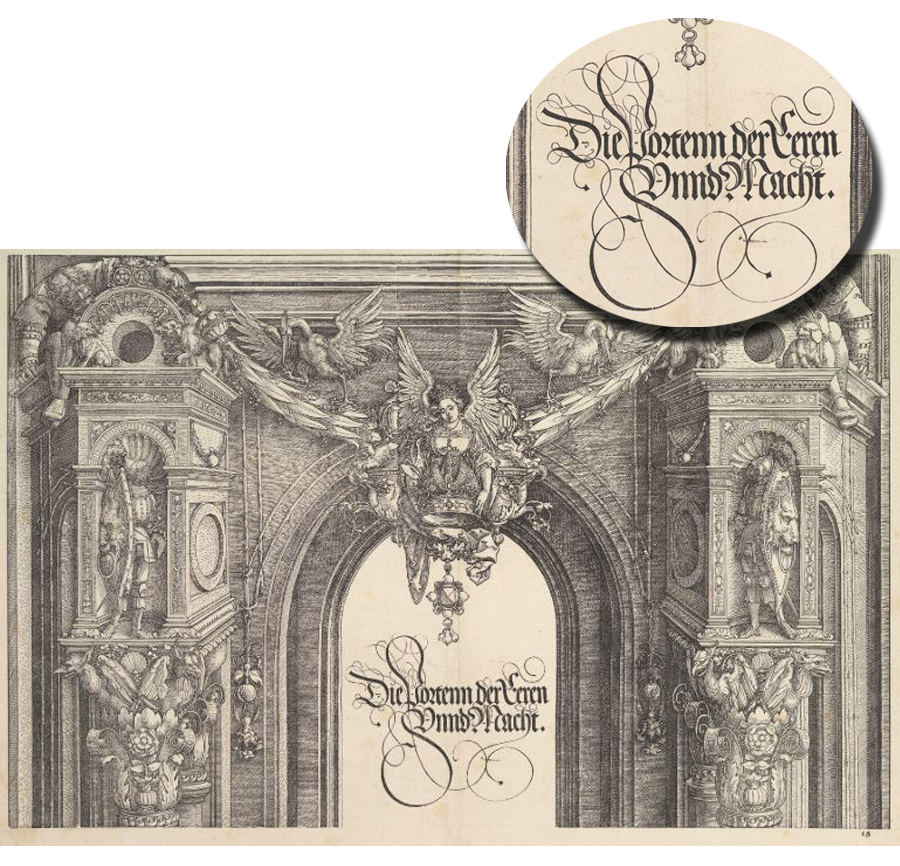

Neudörffer was a celebrated scribe in his day; it is probably his script that appears on Albrecht Dürer’s splendid print, “The Arch of Emperor Maximilian.” And Dürer chose him as the scribe for the inscriptions on his “Four Apostles,” as well.

Metropolitan Museum of New York, Albrecht Dürer, Arch of Honor, c. 1515-1519 (from The Arch of Emperor Maximilian), with inscription likely by Johann Neudörffer.

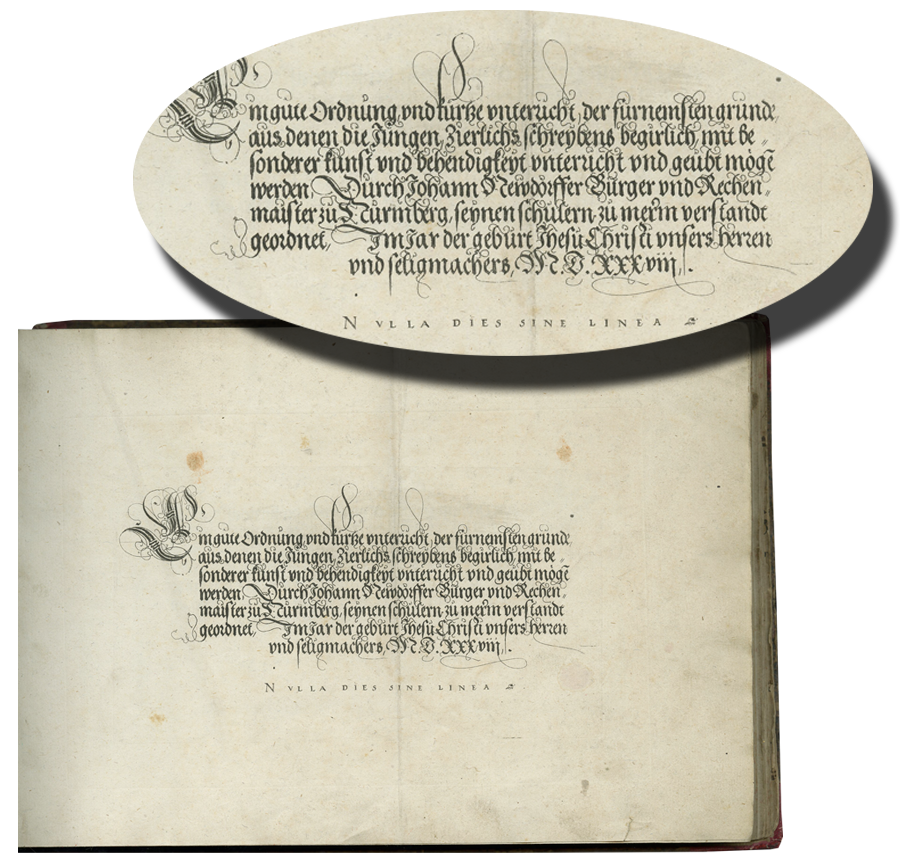

The title of his book makes it clear that it was intended to be used for teaching, Ein gute Ordnung, und kurtze unterricht, der fürnemsten grunde aus denen die Jungen, Zierlichs schreybens begirlich, mit besonderer kunst und behendigkeyt unterricht und geübt mögen werden (A good arrangement and short lesson, primary techniques by which youths, eager to learn fine writing, should undoubtedly be taught by using exceptional art). This is an important point to remember, since modern discussions that refer to “calligraphy books” or “writing manuals” obscure their importance as textbooks which should be studied as part of the history of education.

TM 1005 Johann Neudörffer, Ein gute Ordnung, title page.

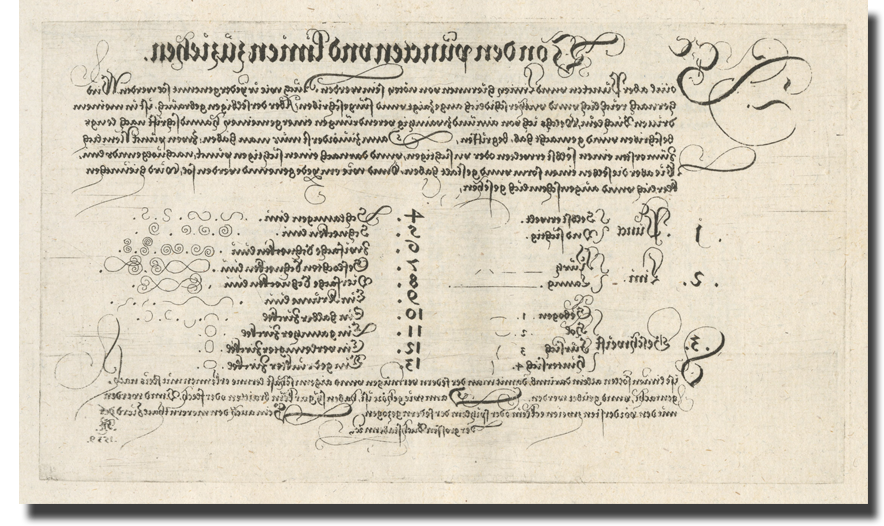

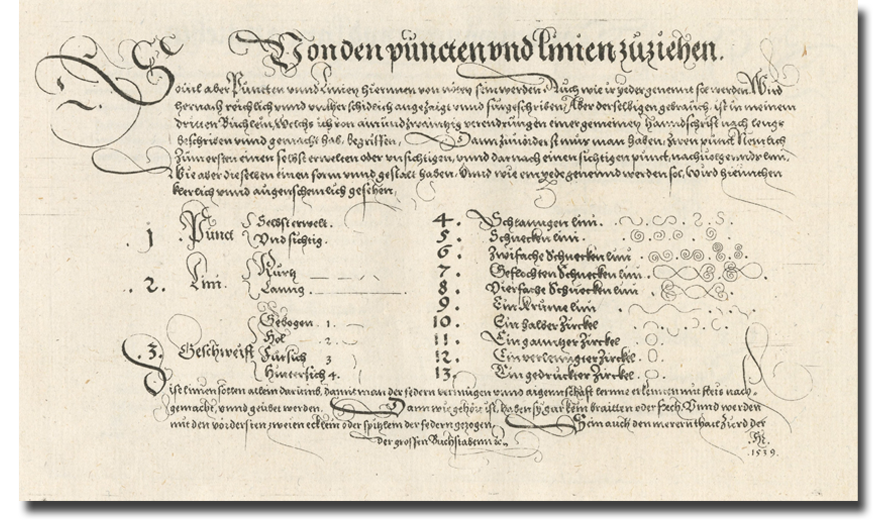

Look at this plate from Ein gute Ordnung.

TM 1005, Johann Neudörffer, Ein gute Ordnung, f. 6.

Having trouble reading it? Of course you are, since it is reversed. One of the innovations of this book is that its plates were produced by copperplate engravings (a first in the history of writing- masters’s books). In copperplate, if a text is engraved in the direction in which we normally read or write (“right-reading”), the print will consequently be a mirrored image.

Its matching plate, reading correctly, is below (technically, it is called a counterproof, made by pressing a fresh sheet of paper onto the mirrored image while the ink was wet). Some copies of Neudörffer’s manual are printed on nearly transparent paper so that the reversed images can be read from the non-printed side. Other copies like Les Enluminures, TM 1005 are on sturdier paper and not all details show through clearly to the other side (although they could have been traced if placed over a window).

TM 1005, Johann Neudörffer, Ein gute Ordnung, f. 5.

Was Johann Neudörffer a good teacher? The copy of Ein gute Ordnung now described on our text manuscripts site, TM 1005, is followed by sixteen pages of calligraphy samples and alphabets copied by Hans Jacot in 1590 when he was a young man of twenty. His handwriting skills were in part learned from his copy of Neudörffer’s book.

Alphabets and writing sample copied in multiple scripts by Hans Jacot in 1590, TM 1005, f. 125.

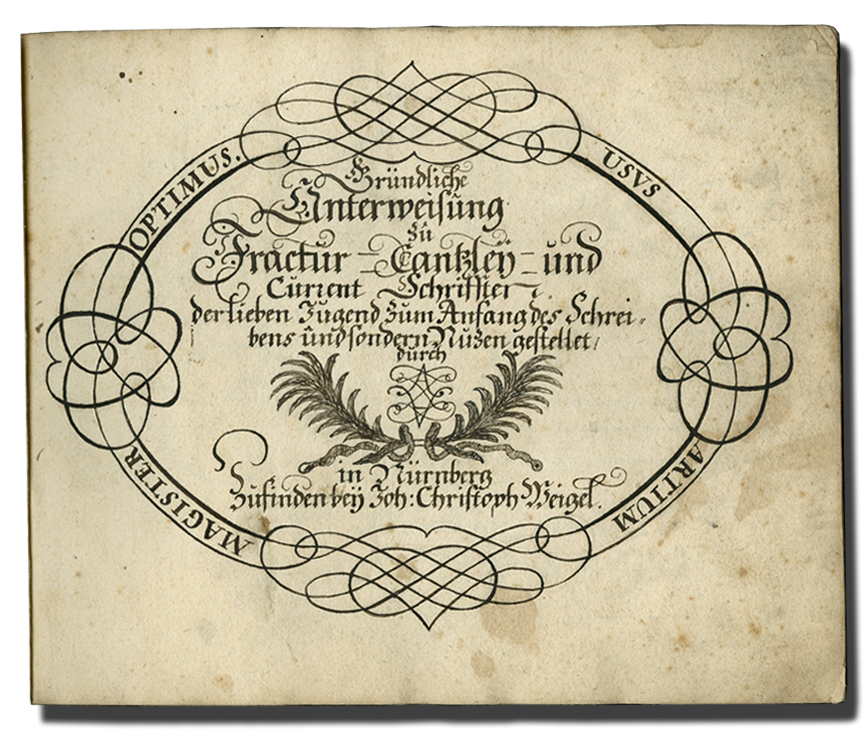

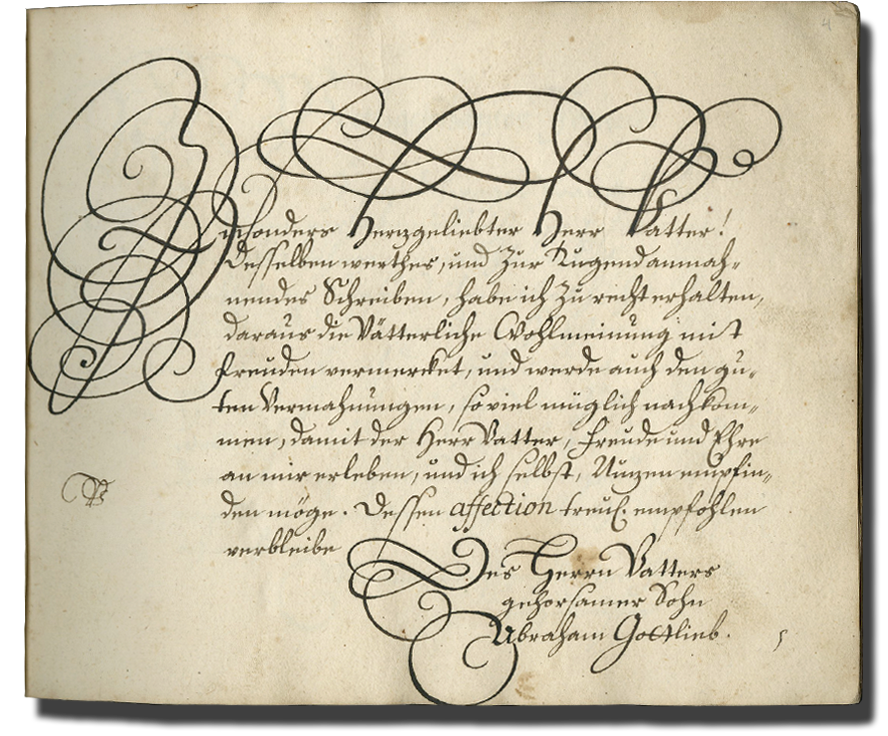

The tradition of German writing masters flourished in the centuries after Neudörffer. A fine example, also from Nuremberg, was copied by an unnamed master (or student) in 1713, entitled, Gründliche Unterweisung zu Fraktur – Canzley – und Current Schrifften der lieben Jugend zum Anfang des Schreibens und sondern Nuzen gestellet durch A. Z. [a monogram, possibly A. A] in Nürnberg Zufinden bey Johann Christoph Weigel (A Thorough Instruction in Fraktur, Chancery, and Cursive Scripts, prepared for the especial utility of dear Youth in beginning to write by A. Z. to be acquired in Nuremberg from Johann Christoph Weigel).

TM 1007, Calligraphy Samples, Nuremberg, c. 1713, f. 1.

TM 1007, f. 4. Sample letter from a son to his father; the text also found in a Latin-German-Czech children’s grammar published in Prague.

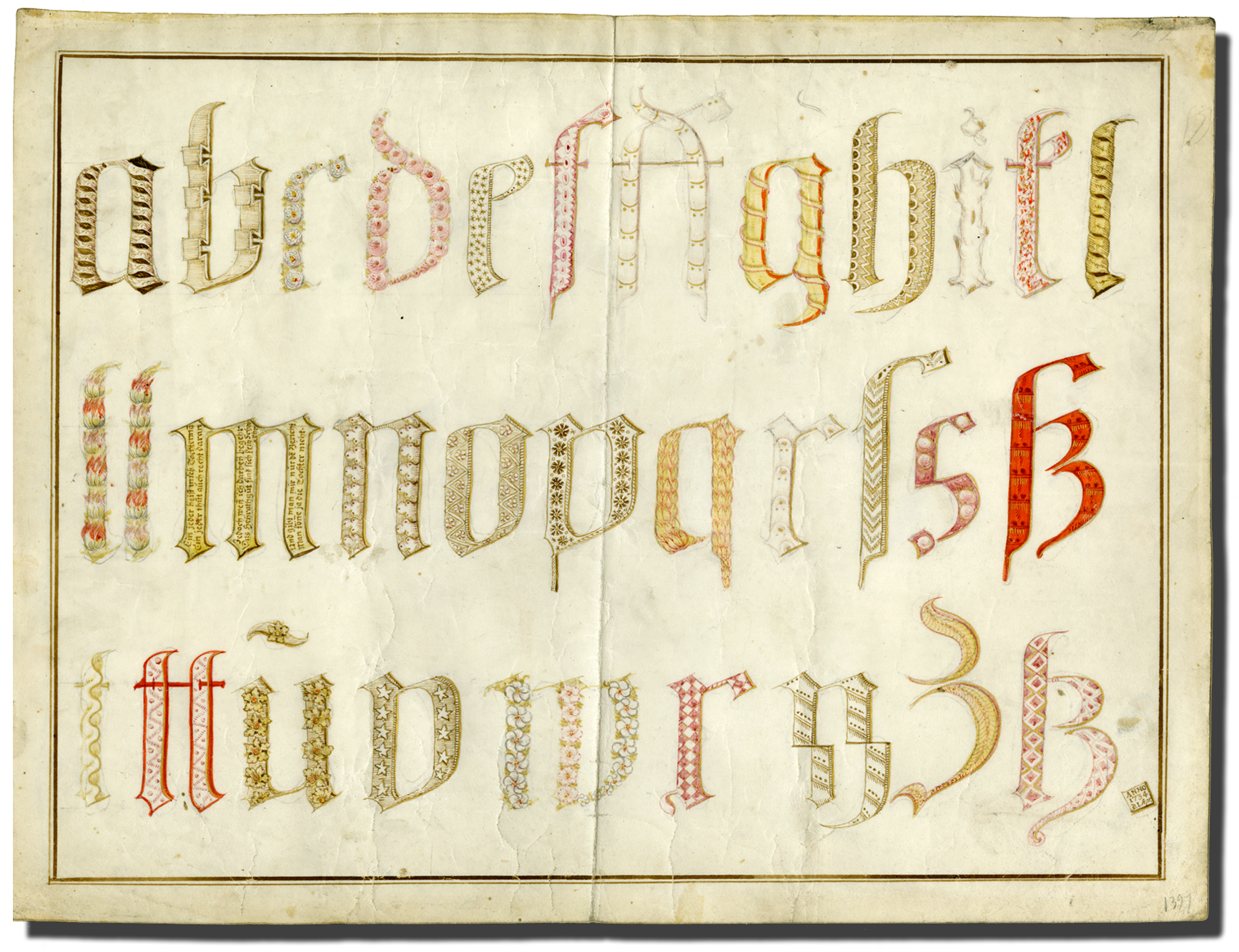

One final example is a delightful and fanciful alphabet sheet, also from Germany, although in this case Augsburg. It was designed to show off the skill of the master calligrapher and schoolmaster, Hieronymus Tochtermann, who copied it in 1734. Can you find his name amidst the flowers, stars, leaves and other motifs that decorate his alphabet?

TM 848, Calligraphic Alphabet by Hieronymus Tochtermann, Augsburg, 1734.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”