Out on your summer vacation, perhaps looking for that ideal Instagram photo, have you ever gazed in wonder at a painting and thought “how did they do that?” Well, artists’ secrets are sometimes revealed in unexpected places – like the flyleaf of a manuscript.

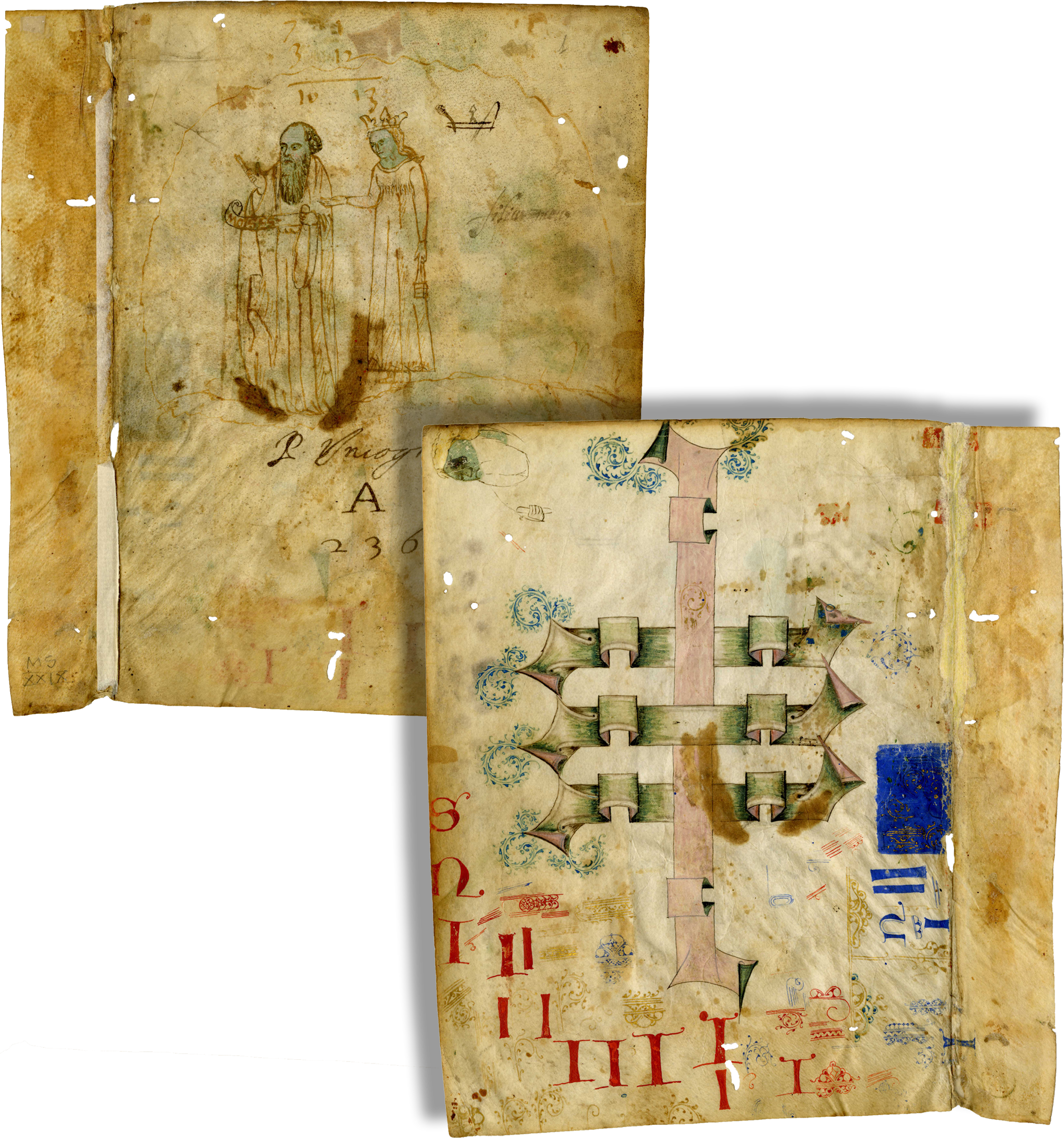

This parchment test sheet reveals a few of those secrets, filled with pen and brush trials showing the hand(s) of an artist or workshop experimenting with colors and letterforms. It is a rare glimpse over the shoulder of an early Renaissance artist at work.

Les Enluminures, Test Sheet with Patterns, Sketches, and Pen Trials (188 x 168 mm.), Northern Italy, c. 1400

The holes left by book worms and the long crease make it clear that the parchment sheet was later used as a flyleaf in a book or manuscript. Although doodles and pen trials are often added to blank space in medieval books, the sheer number and position of the trials on our leaf suggests it was first and foremost a loose sheet of parchment, probably from a workshop in Northern Italy around 1400. (For a fantastic roundup of medieval doodles and pen trials go to Erik Kwakkel’s blog post “Doodles in Medieval Manuscripts”.)

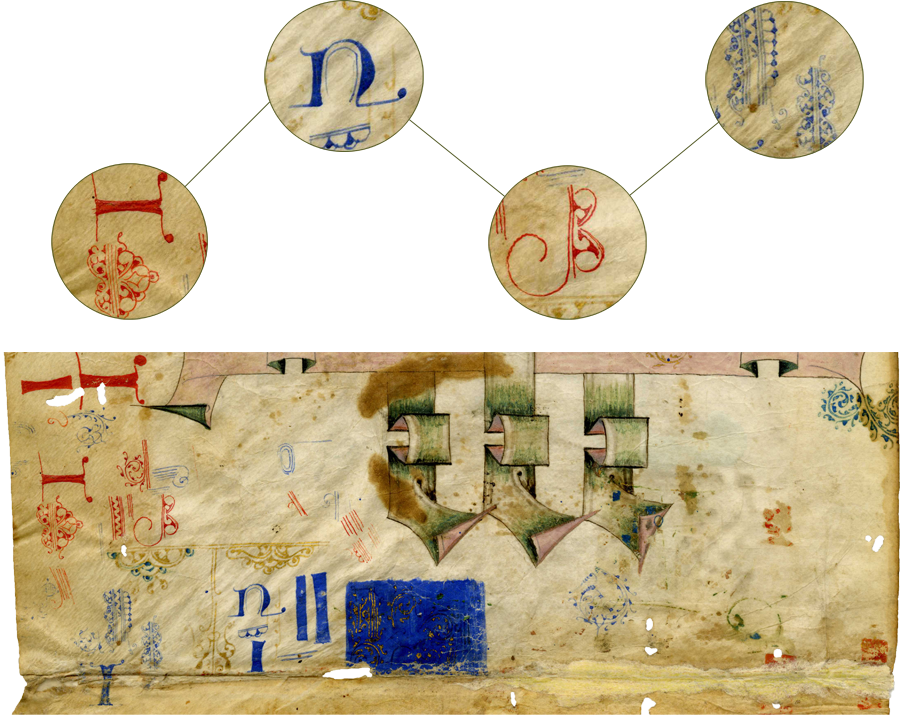

Pen and brush trials and pen-work motifs in a range of colors

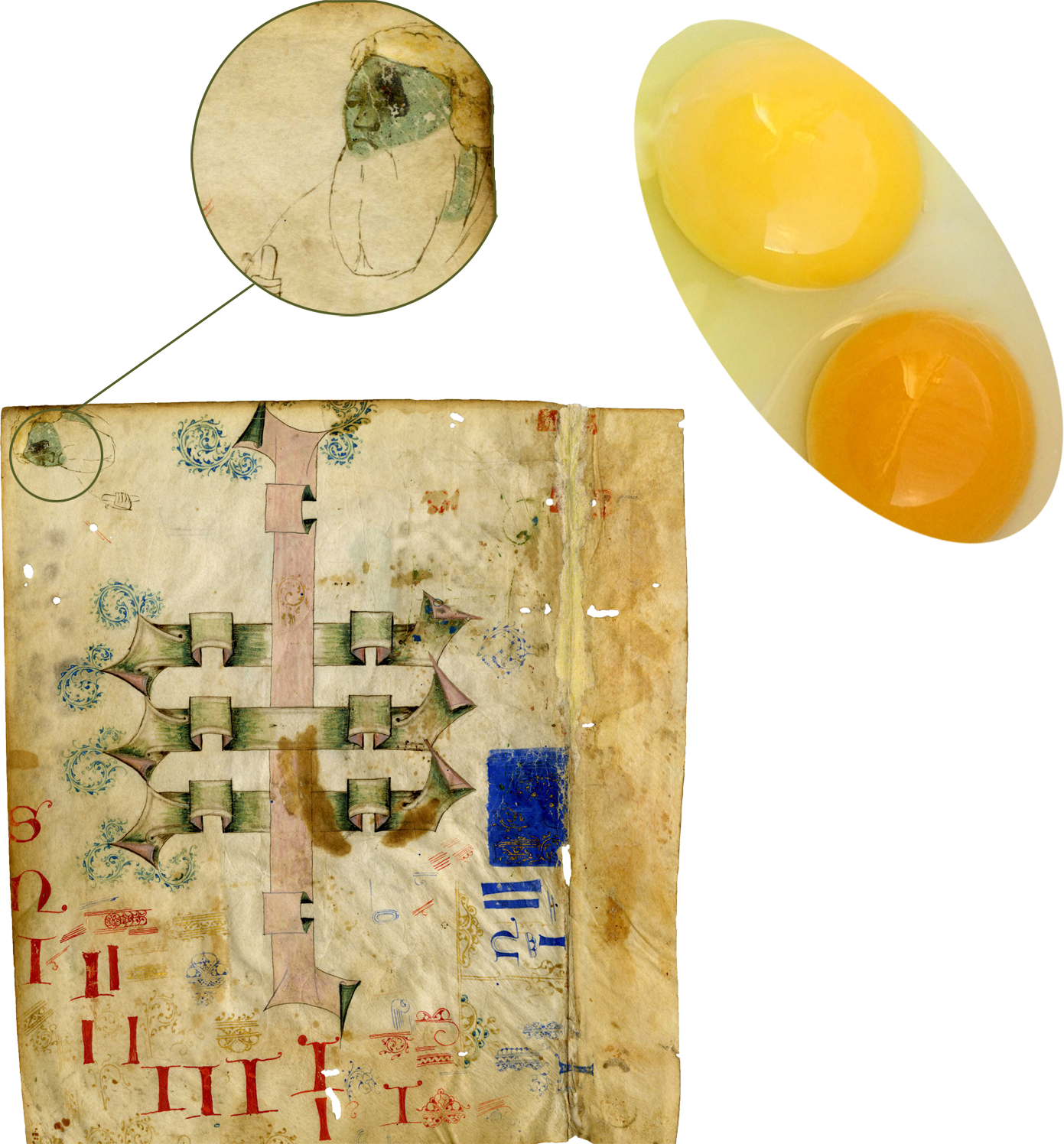

One way to localize and date our test sheet is to look at the specific way that faces are painted, in this case using layers of green pigment called green earth or terra verde. This method is outlined step-by-step in the chapter “How to Paint Faces” in the handbook Il Libro dell’Arte, written around 1400 by Cennino Cennini (c. 1370-c. 1440), who was in a sense the artistic great-grandchild of Giotto. Cennini’s instructions reveal methods used by Giotto in the wall paintings of the celebrated Scrovegni Chapel in Padua – definitely a prime Instagram spot to judge by the number of tags.

Scrovegni Chapel (or Arena Chapel), Padua, Italy, with wall paintings by Giotto completed 1305

The secrets revealed in Cennini’s instructions are so valuable that artists, conservators, and even art forgers (reportedly) have continued to use them. First Cennini says “take a little terre-verte [green earth] and a little white lead, well tempered, and lay two coats all over the face, over the hands, over the feet, and over the nudes.” This first step can be seen in the face of a bearded man on the front of our leaf with a thin coat of green earth. Cennini specifies that the faces of young people “with cool flesh color” should be tempered with pale yellow yolks from a “town hen’s egg,” as opposed to the eggs from farm hens which are more orange, like the free-range eggs from the farmers’ market.

Pale yellow and orange egg yolks used to vary flesh tones

After building layers of green earth with lead white, Cennini next says to create flesh colors with pinks and reds, specifying cinnabar for wall paintings and vermillion for panel paintings (vermillion also being used in manuscript illumination). After using multiple layers to “pick out the forms of the face,” noses and eyes are later outlined in brown or black. A bearded man (perhaps Moses) and a crowned woman on the reverse of our leaf show later stages of this kind of verdaccio, with vermillion mixed into lead white and painted over the foreheads and cheeks.

Somewhat more developed verdaccio

It’s unclear why only the faces of these figures were painted, or how they relate to some other project (to test the qualities of egg yolks? trying their hand with something new?) but the varying levels of verdaccio on either side of this test sheet bring to life the instructions written down by Cennini over 600 years ago. The many letters and pen-work motifs added to the leaf were highlighted by Laura Light in our previous blog post for May, and a full description available at the Les Enluminures website.

Mark Lansburgh

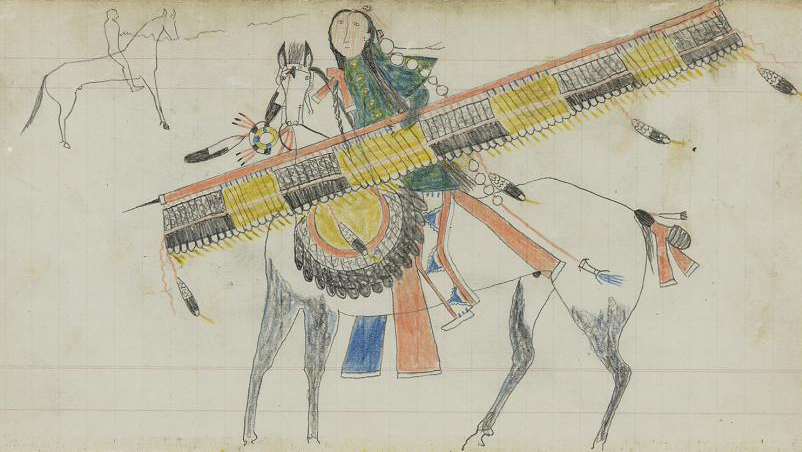

Our leaf was later owned by the art historian Mark Lansburgh (d. 2013), who assembled an important collection of Native American ledger drawings in addition to a collection of European drawings and manuscript leaves that charted the development of drawing as an art form. Drawn on paper from notebooks and other sources (such as ledger books, from which it gets the name), ledger drawings show captivating images created at a moment of shifting culture in the Great Plains in the middle of the nineteenth century and later.

Untitled (A Crazy Dog Society Warrior), detail, unknown artist, from the "Frank Henderson" Ledger, about 1882 (p. 172), graphite and colored pencil on laid ledger paper; Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, Mark Lansburgh Ledger Drawing Collection, Partial gift of Mark Lansburgh, Class of 1949, and partial purchase through the Mrs. Harvey P. Hood W'18 Fund, and the Offices of the President and Provost of Dartmouth College (2007.65.51)

Ledger drawings can also reveal the secrets of drawing and painting methods used by artists over time. Transitioning from animal hides to paper and pencil, artist’s drawing methods adapted alongside changes in media (not unlike Cennini’s instructions specific to wall painting, wood panels or parchment). A lecturer at Colorado College, Mark Lansburgh also taught at Stanford and New York University. The Mark Lansburgh Ledger Drawing Collection was acquired by the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College in 2007.

Speaking of Instagram, make sure to follow us (@lesenluminures) and also at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures) and share your summer discoveries with us!

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”

For the quotes from Cennini’s handbook reproduced here, see The Craftsman’s Handbook: The Italian “Il Libro dell’ Arte,” Cennino d’Andrea Cennini, trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr., New York, 1960, pp. 93-94.