It wasn’t easy being king in the Middle Ages. This was a common conclusion drawn in the literature and historical writing of the period. Writers like Boccaccio chronicled great men and women’s losses of power and privilege. And the concept of the Wheel of Fortune, of fate’s unpredictability, permeated medieval culture. With all a king’s power came vulnerability. Having ascended to the heights of social and political prominence, kings had the furthest to fall.

Lady Fortune dictates the fates of king and commoner alike, and depictions of her wheel emphasize the transience of good and bad fortune, as in this manuscript, John Lydgate’s Troy Book and Siege of Thebes, London, British Library, Royal MS 18 D.ii, f. 30v (detail).

This was particularly true in times of turmoil, like the War of the Roses, an English civil war fought over a period of thirty years. Two branches of the royal family, the Lancastrians and the Yorkists, fought for the throne, their red and white rose badges giving the war its name.

Members of the Lancastrian and Yorkist factions pick roses to indicate their allegiances in Henry Payne’s 1908 painting of a scene from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, The Plucking of the Red and White Roses in the Temple Garden, London, Palace of Westminster

Whether your associations with the War of the Roses stem from history classes, Shakespeare’s history plays (Richard III does make a pretty lasting impression), or even Game of Thrones (did you know the War of the Roses was a major inspiration for George R. R. Martin’s immensely popular novels?), it undeniably endures in the popular imagination.

Subtract the dragons and the white walkers and Westeros’s politics have rather a lot in common with those of fifteenth-century England!

It all began with questions over who ought to succeed the popular and long-lived Edward III. He was succeeded by his grandson, Richard II, but Richard’s first cousin deposed him and became the land’s first Lancastrian monarch, Henry IV. The Lancastrians held onto the throne for several generations, but the Lancastrian Henry VI was regarded as a weak, ineffectual king, afflicted with bouts of insanity. Facing mounting losses in England’s wars with France, unstable rule at home, and an uncertain succession, Henry VI’s wife, the indomitable Margaret of Anjou, and his powerful, popular, and wealthy cousin, Richard, Duke of York, led rival factions jockeying for power.

Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou surrounded by their court as depicted by the Talbot Master in the Talbot Shrewsbury book, a book of poems and romances given to Margaret as a wedding gift, London, British Library, Royal MS 15 E.vi, f. 2v (detail). Richard, Duke of York, helps support a French genealogy on the facing page of the Talbot Shrewsbury book, f. 3 (detail)

Cersei Lannister (clearly inspired by the fierce and beautiful Margaret of Anjou) and Ned Stark (very much a Richard, Duke of York figure) face off for the last time in You Win or You Die, Season 1, Episode 7 of HBO’s Game of Thrones

In the battles that ensued over the next thirty years, Henry was captured and then restored to the throne before dying in captivity. Margaret led Lancastrian forces in battle, where she saw her only son killed. Richard was eventually beheaded and his head was displayed on a pike at York, wearing a paper crown. His son took the throne as the first Yorkist king, Edward IV, but Edward’s sons quickly lost throne and freedom at the hands of their infamous uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who effectively imprisoned them in the Tower of London. Their uncle’s reign as Richard III was brief, however; exiled Lancastrian, Henry Tudor, led a rebellion that ended in Richard’s death and burial under what would eventually become a city council car park.

The earliest surviving portrait of Richard III, painted c. 1520, London, Society of Antiquaries. Alongside: Shakespeare’s Richard III shaped the king’s modern reputation as an unapologetic villain. Kevin Spacey offered a modern interpretation of Richard III’s despotic villainy in the 2011/2012 Bridge Project production of Richard III, directed by Sam Mendes at the Old Vic, London and the Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York

So, again, not an easy time to be king. To put it mildly.

Shown partially unfurled here, this roll features a history of the kings of England, TM 840, England, possibly London or Westminster?, c. 1505-1525

That’s where rolls like this one come in. A genealogical roll of prodigious length – at over twenty feet, it would be about two stories tall! – our roll traces the history of the kings of England back into distant days of legend. The earliest membranes feature royal predecessors like Lud, legendary namesake of London, and, of course, King Arthur. The history of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England, and their gradual consolidation appear in slightly later membranes before the Norman Conquest brings yet another line to the throne.

The legendary Lud is one of the first English rulers featured in this roll, TM 840, membrane 1 (detail). The consolidation of the Heptarchy under the Anglo-Saxon King Egbert, TM 840, membrane 6 (detail)

Though rolls like this one owe much of their content to earlier English chronicles, they were produced in far greater numbers during the fifteenth century, particularly during the War of the Roses. (Our roll, more unusually, dates to the sixteenth century, a point of interest to which I will return below.) But why might people have taken such an interest in Lud or Egbert centuries after their deaths amid a period of shifting allegiances and bitter warfare?

Our royal genealogical roll would have drawn on examples like our beautifully illustrated copy of a genealogy of Christ by Peter of Poitiers, Compendium historiae in genealogia Christi, England, Oxford?, c. 1230-1250

Swooping in from the green Norman line on the left and occupying a central, crowned roundel, William the Conqueror was a real red-letter monarch, TM 840, membrane 8 (detail)

Quite simply, rolls like this one were tools of propaganda. Look at the presentation of the Norman Conquest (see above) and the Anarchy (see below). Even before the Lancastrians and Yorkists were at each other’s throats, these were two notable periods of rupture and conflict in the island’s history: first an invasion and then a brutal civil war. Neither the conquering William nor Stephen, king during the civil war, was a clear successor to the previous monarch. Though William claimed that the previous king had promised him the throne, there were two other claimants. And Stephen snatched the throne after Henry I died with no male heir, even though he had sworn to support the claim of Henry’s daughter, the Empress Matilda.

The red line snaking around Stephen links the prior king, Henry I, to his grandson, Stephen’s successor, Henry II, TM 840, membranes 8 and 9 (details)

The bends and twists of the colored branches – representing lines of descent – underscore the movements of different families in and out of power. But the format of the roll, with membrane after membrane of large crowned roundels proceeding down the center of the page, creates the impression of continuity where there was none necessarily to be found. The man whose crowned roundel appeared at the foot of this roll would appear as the rightful, even inevitable, king and the latest in a series of great names that include Arthur, Alfred the Great, and, more recently, Edward III.

As this roll makes abundantly clear, Edward III had numerous noble offspring, the ancestors of the main combatants in the War of the Roses, TM 840, membrane 12 (detail)

This would have been all the more valuable when a king’s hold on power was tenuous and his people looked for leadership elsewhere. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that this roll follows the text of a chronicle originally written for Henry VI and appears to favor the Lancastrians in its account of England’s recent history. For example, even though it was made well after the War of the Roses, it neglects to identify the Yorkist rulers as part of the long line of English monarchs.

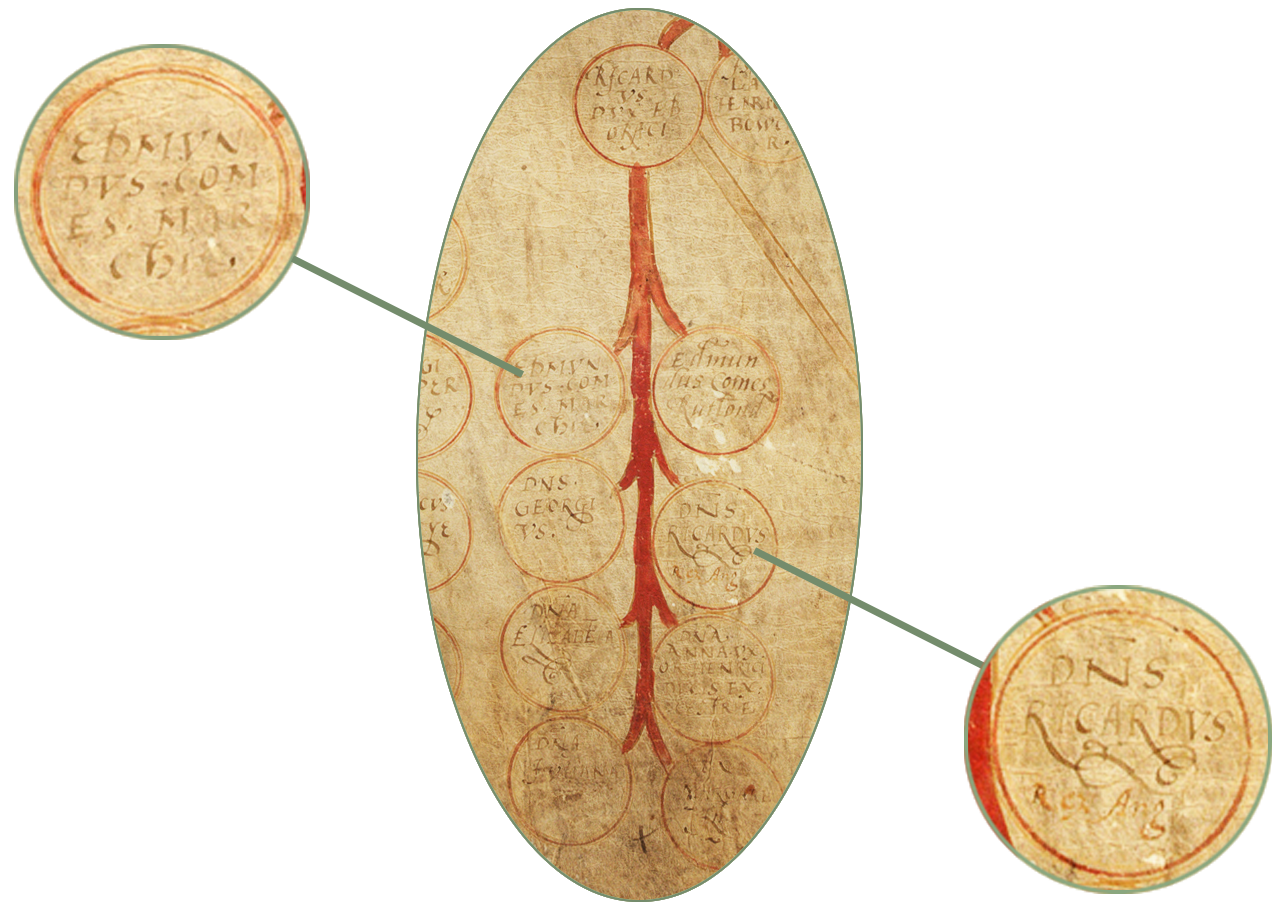

It took a later reader to identify Richard III as “Rex Anglie” – as for Edward IV, not only is he not identified as a king, but, in what may have been an epic sixteenth-century troll, his name is given as “EDMVNDVS,” TM 840, membrane 12 (detail)

Produced during the reign of the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, this roll and its chronicle may have been embraced as a piece of enduringly useful propaganda. Henry’s claim to the throne was by no means secure, since he was a bastard descendant of the Lancastrian house and the latest in a string of kings by conquest. He made canny use of propaganda to shore up his power and legitimize his reign; for example, he highlighted his union with Elizabeth of York by blending the red and white roses into the Tudor rose. One can only imagine that this roll’s chronicle might have appealed to a similar impulse, since it could be used to defend the legitimacy and prestige of his Lancastrian forebears.

The red and white Tudor rose fills the border surrounding this depiction of an earlier royal wedding between the Lancastrian Henry V and Catherine of Valois, part of a continuation of the Grande chroniques de France presented to Henry VII as a gift, London, British Library, Royal MS 20 E.vi, f. 9 (detail)

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”