Detail from a monastic manuscript, Carthusian Rules and Sermons for Visitation, TM 333, f. 1, Northern Italy (Venice?),

Detail from a monastic manuscript, Carthusian Rules and Sermons for Visitation, TM 333, f. 1, Northern Italy (Venice?),

ca. 1500-1525, with later additions c. 1534

Here’s a medieval manuscript personality test: when you look at these pages below and think about how this book came into being do you (a.) marvel at the skill and hard work of their makers or (b.) think about all the ways in which things could have gone horribly wrong?

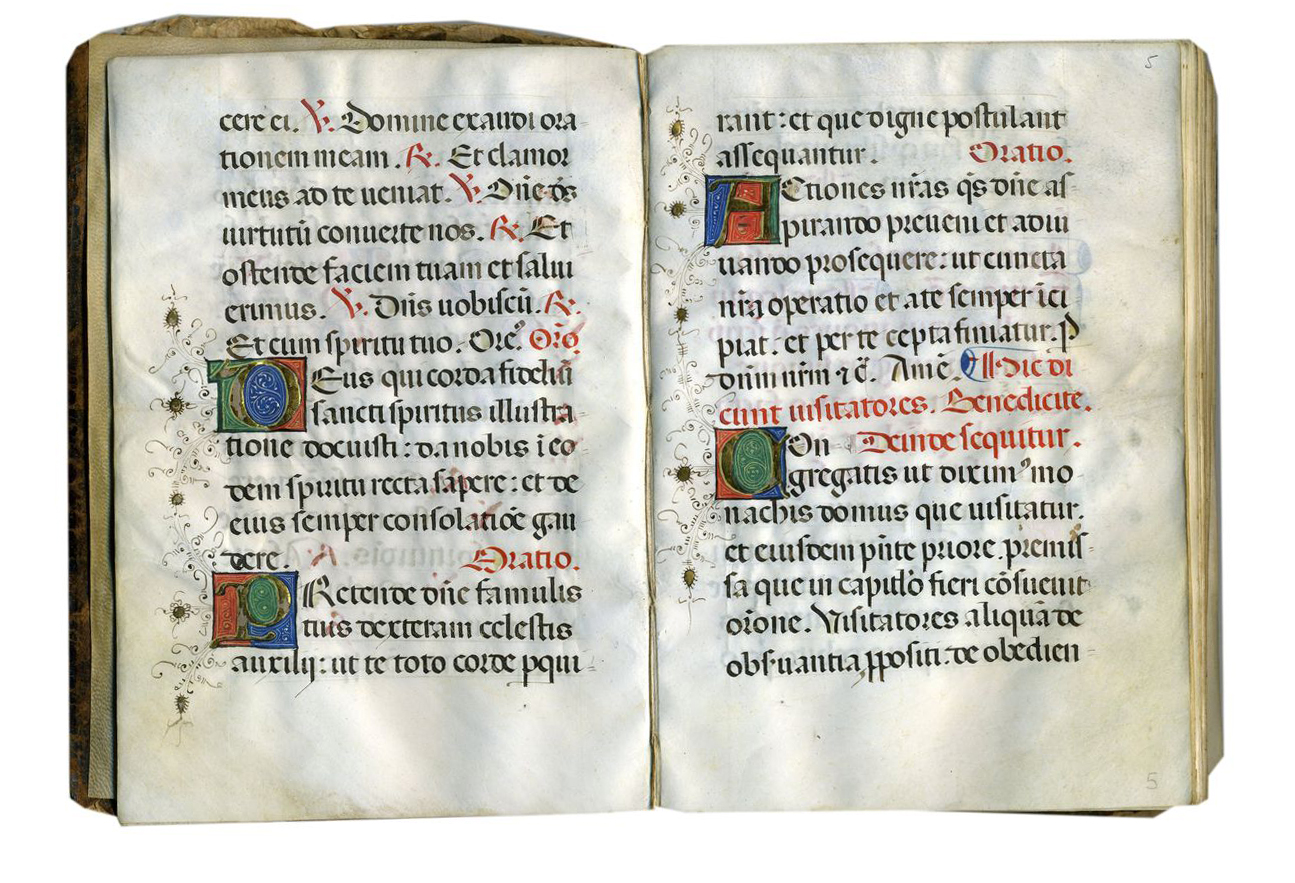

An illuminated opening from the same manuscript,TM 333, ff. 4v-5

Making decorated medieval manuscripts like this was a time-consuming, multi-stage process. Whether it involved several people laboring over different aspects of a book’s production or one person working in multiple capacities, the factors of time and complexity – to say nothing of funding and availability of materials – left plenty of room for error.

Take the red headings on these pages, known as rubrication (or rubrics) on account of their color (in Latin the verb rubricare means ‘to color red’).

Detail from TM 333, f. 5

Detail from TM 333, f. 5

Rubrics like this one would have been written in after the main text had been copied. The scribe had to leave space for them as he or she copied the main text and then the same scribe or a separate rubricator had to go back over the manuscript, copying the correct headings in their proper places.

This (very faded!) rubric has been copied by the primary scribe in this historical manuscript, an Italian translation of the Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum of Martinus Polonus, TM 117, f. 128v (detail), Northern Italy (Vicenza), dated 1472

This (very faded!) rubric has been copied by the primary scribe in this historical manuscript, an Italian translation of the Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum of Martinus Polonus, TM 117, f. 128v (detail), Northern Italy (Vicenza), dated 1472

Same manuscript, same scribe, new rubricator. Here a second scribe has added a rubric that the first scribe missed in

Same manuscript, same scribe, new rubricator. Here a second scribe has added a rubric that the first scribe missed in

TM 117, f. 130 (detail)

This didn’t always work according to plan. Below we see a manuscript that simply did not make it through all of these stages of production. The empty spaces in the second column on the left page indicate that the scribe anticipated the addition of rubrication (and also two painted initials).

An opening from the Summa de virtutibus of William Peraldus in a Dominican miscellany, TM 839, f. 26v, Eastern France, Southwestern Germany, or Switzerland (Upper Rhine), c. 1400-1440

In fact, a close look at the margins of this page reveals that this scribe, like many others, took practical measures to ensure that rubrications would be accurate when they were added. Here beside an empty space left for a new chapter heading we can see a note in the margin spelling out that heading, “De oratione” (Of prayer).

Further down on the same page, a whole line has been left empty for a longer chapter heading to be added (see below). Again, the scribe has left a note identifying the appropriate heading, “Octo sunt que nos incitant ad orationem” (Eight are the things that urge us on to prayer), this time at the bottom of the text column, where it can fit and be read more easily.

Written in ink on paper in close proximity to the main text, these prompts, once added, became permanent additions to the page. This is fortunate for modern manuscript scholars, since these prompts reveal part of the manuscript-making process. And, in this case, this was presumably appreciated by medieval readers as well, since these notes for the rubricator remain the only chapter headings in this text. They would have made it much easier for a medieval reader to navigate this rather lengthy treatise on the virtues Christians were expected to cultivate.

Why don’t we find them in manuscript margins as a matter of course, then? For one thing, they were not always necessary, especially for scribes adding their own rubrics and working from another copy of the same text. In other cases, though, prompts like these served as temporary aids. As many manuscripts testify, medieval makers and collectors of books valued the look of broad, clean margins. Notes for rubricators could be removed so as to preserve these wide open spaces.

An opening from a legal reference book, the Margarita Decreti et Decretalium of Martinus Polonus, TM 642, ff. 33v-34, Italy, c. 1425-1450

An opening from a legal reference book, the Margarita Decreti et Decretalium of Martinus Polonus, TM 642, ff. 33v-34, Italy, c. 1425-1450

In the opening just above, we can see that the scribe left prompts in the inner and outer margins. The notes in the gutter, or inner margin, do survive intact, but those in the outer margin have been largely cropped away.

Where prompts were not being written in ink on paper, there were more options for their removal. Can you make out the notes for the rubrication in this opening? Because they have been written on parchment, the scribe was able to go back and largely scrape them away after adding the rubric. Now they are barely visible:

An opening from a medieval bestseller, the De miseria humanae conditionis of Lotario dei Segni (Pope Innocent III),TM 814, ff. 8v-9, Northern France, c. 1450-1475

An opening from a medieval bestseller, the De miseria humanae conditionis of Lotario dei Segni (Pope Innocent III),TM 814, ff. 8v-9, Northern France, c. 1450-1475

Want to see more of the manuscripts featured here or read about their contents? You can learn more about TMs 117, 333, 642, 814, and 839 in their full descriptions, all up on our Textmanuscripts site.