This week’s post is dedicated to a unique, unpublished wine manuscript from the fifteenth century: “the Statutes Regulating the Wine Trade and Transportation in Bologna.”

TM 274, Statutes regulating the Wine Trade and Transportation in Bologna, ff. 1v-2 (detail)

Wine-growers among you may start watching the weather pretty closely in the early summer months for its effect on the harvest-to-come. Wine-drinkers – at least those who live in New York – might want to attend MetFridays for the newly inaugurated wine tastings at the Cloisters, where you can even admire some trailing grape vines in the enclosed garden.

The Cloisters (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Or, read on for tidbits about the early history of wine.

The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans all drank wine. Effects of the beverage are widely featured in the visual arts: from episodes in the Old and New Testament (e.g., the Drunkenness of Noah), Greek mythology (Dionysius as God of Wine), and Persian legend (King Jamshid and the beautiful princess). In beer-drinking Germany, the reformer and bon vivant Martin Luther extolled the virtues of both beer and wine, although he claimed: "Beer is made by men, wine by God!". The earliest evidence of the existence of wine technology comes not from France, the modern world’s pre-eminent wine capital, but from Bronze Age Armenia in c. 4000 BC.

From left to right: a woman having wine in solitude, from Chehel Sotoun pavilion in Isfahan, Iran, 17th century (detail); statue of Dionysus, Marble, 2nd century CE, Louvre; Kings MS 5, f. 15r c 1395-1400, Biblia Pauperum, "Noah Drunk" ( detail) , British Library.

But, what about wine in medieval manuscripts? Those familiar with the calendars of illuminated Books of Hours, chronicling daily life through the yearly cycle, will remember that September, or sometimes October, is usually illustrated with the grape harvest as the Labor of the Month coupled in this case with the Zodiac Sign.

BOH 102, the Monypenny Hours, France, Paris, c.1490, ff. 10v-11, October (detail)

In the autumn, the picking of and stomping on grapes must have been a familiar sight in the countryside in medieval Europe. What else do we know about wine in the Middle Ages? An excellent volume of Mediaevalia (vol. 30) reveals what made wine tasty to medieval drinkers and how dietary rules (according to the seasons of the year, to the ages of man, and to social classes) affected wine drinking. Interesting evidence about the colors of wine, wine-producing regions, and even about wine as a sacred commodity in religion also comes to light.

Written in Bolognese dialect, our manuscript comes from Emilia-Romagna. Today, this fertile province is one of Italy’s most prolific wine-producing regions, covering more than 136,000 acres across the entire width of the Italian peninsula.

Tenuta Bonzara: a renowned vineyard near Bologna

It is also one of the older wine areas. We know that grapevines were planted there by the Etruscans who transported wine along ancient roadways to other areas of Italy as early as the seventh century before Christ.

By the mid-fifteenth century, the wine trade was already well-regulated in Bologna. Some forty-eight chapters in our manuscript cover everything from the retail and wholesale cost of wine (chapters 1 and 2) to the parking of the wagons full of barrels of wine at the city gates and the housing for the wholesalers who drove the wagons (chapters 42 and 48). These medieval city gates still exist in modern-day Bologna.

Bologna, Porta Saragozza, built in the 13-14th centuries.

Special reduced prices for wine applied to those in military service (chapter 3). In certain respects little has changed in wine-making and retailing: it was forbidden to mix water with wine, and punishments were meted out for those who did not obey (chapter 12).

TM 274, Statutes regulating the Wine Trade and Transportation in Bologna, ff. 2v-3. Chapter 12, rules concerning mixing water with wine (detail)

In other respects today’s wine drinkers are more moderate and, hopefully older. In medieval Bologna people were free to drink up to five bottles (two liters) of wine per day within the walls of the city or under its gates. But they had to be at least fourteen years of age (chapter 24)!

TM 274, Statutes regulating the Wine Trade and Transportation in Bologna, ff. 6v-7. Chapter 24, on who can drink wine and how much (detail)

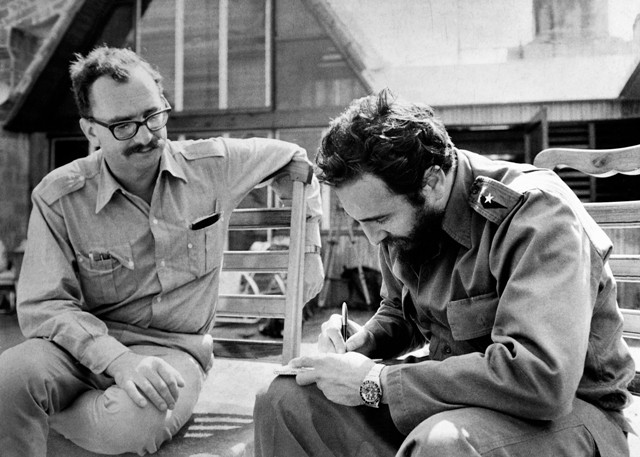

Where did such an extraordinary volume come from? In the twentieth century, the manuscript was part of the famed Giannalisa Feltinelli Foundation Library. Amassed by the publisher, visionary, and revolutionary Giangiacomo Feltrinelli (d. 1972), whose life is picturesquely recounted in the book by his only son entitled “Riches, Revolution, and Violent Death,” the vast library counted more than 200,000 volumes sold in eight sales at Christie’s in New York in 1997. Many of the volumes were devoted to the political, economic, and social history that fundamentally interested their owner.

A picture of Giangiacomo Feltrinelli with Fidel Castro.

Nothing is known for sure, however, of the manuscript’s earliest history. The volume bears no ex-libris or original signs of ownership. But, there is one clue. A pointing hand in the margin signals a passage of special interest to a tax collector

TM 274, Statutes regulating the Wine Trade and Transportation in Bologna, f.8 (detail of the pointing hand)

Perhaps our volume, so full of legal guidelines, served a dutiful civil servant charged with regulating the trade of wine in medieval Bologna.

Not only is the present manuscript a precious document for the study of the medieval wine trade but also for linguistic, monetary, and socio-economic studies in Emilia Romagna. For a full description and illustrations, click here.

Cheers! Chin chin! Bottoms up! Santé!