Look too briefly at the book below and it might trick you. The faded title written hastily upon its modest binding proclaims it to be a book of good recipes for human bodies and for horses.

Signs of wear on the contemporary limp parchment binding of this miscellany of medical, magical, and alchemical recipes testify to its having been well-used, TM 843, Central Italy (Urbino?), c. 1520-1540, front cover with detail shown upside down.

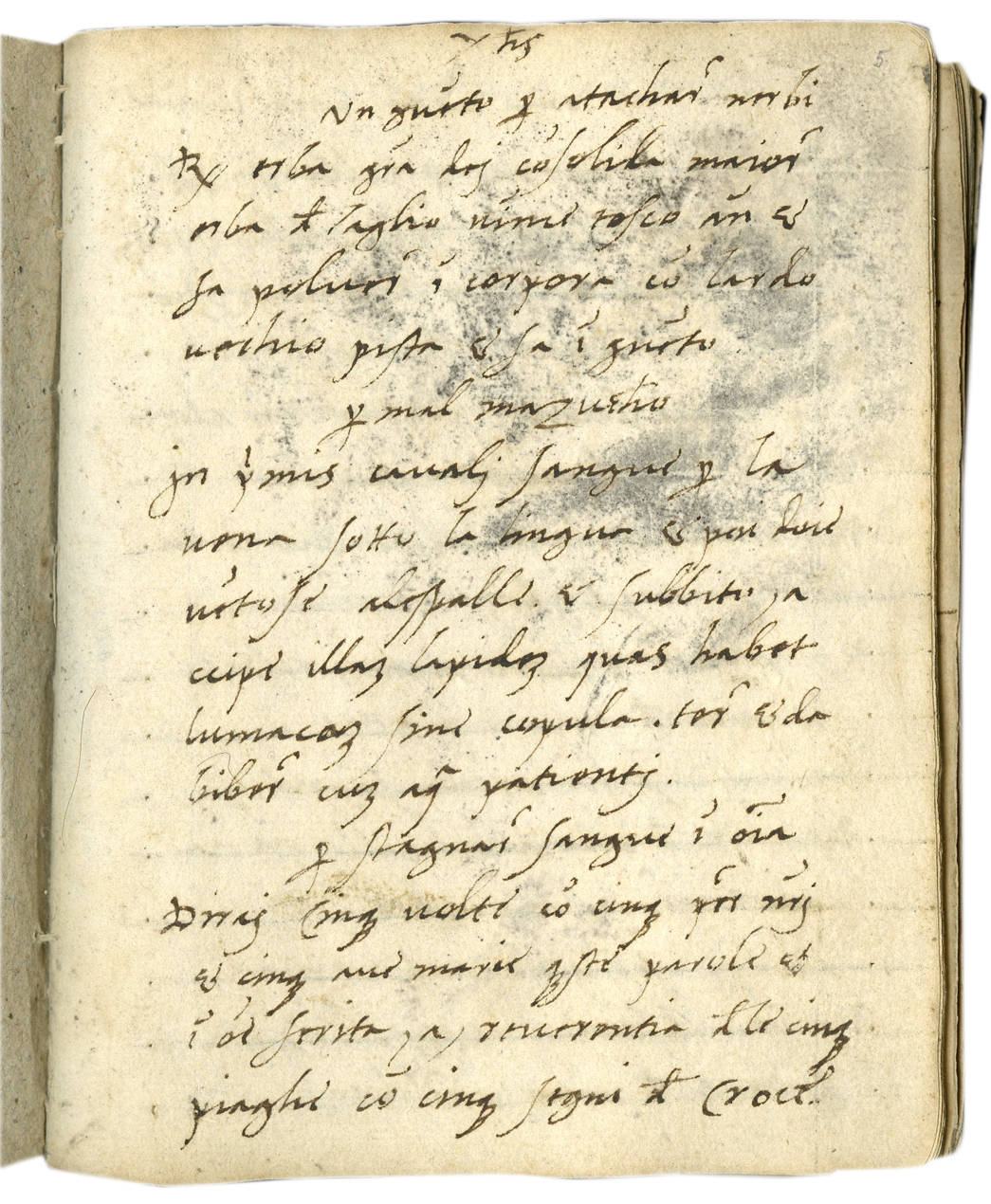

Open the book to its initial pages, and it appears to be just that, a book of medical and veterinary recipes. Compilations of technical and medical recipes like this one, known as books of secrets, abounded in the sixteenth century, circulating in manuscript and in print. The recipes here tend to be fairly brief and practical. Bitten by a cat? Mix galbanum (a bitter resin), black pitch, and gelding fat to make an ointment. Suffering from a dry catarrh? Bring a pound of apples to a foaming boil, remove from the flame and let it cool, and then stir in ground rosemary flowers, nutmeg, and a quantity of cinnamon and cloves until completely incorporated. Then take a chestnut-sized dose in the evening and morning. And, presumably, enjoy that the treatment can double as a tasty snack.

Recipes for human and equine medicines share the opening pages of this volume, as exemplified here, TM 843, f. 5

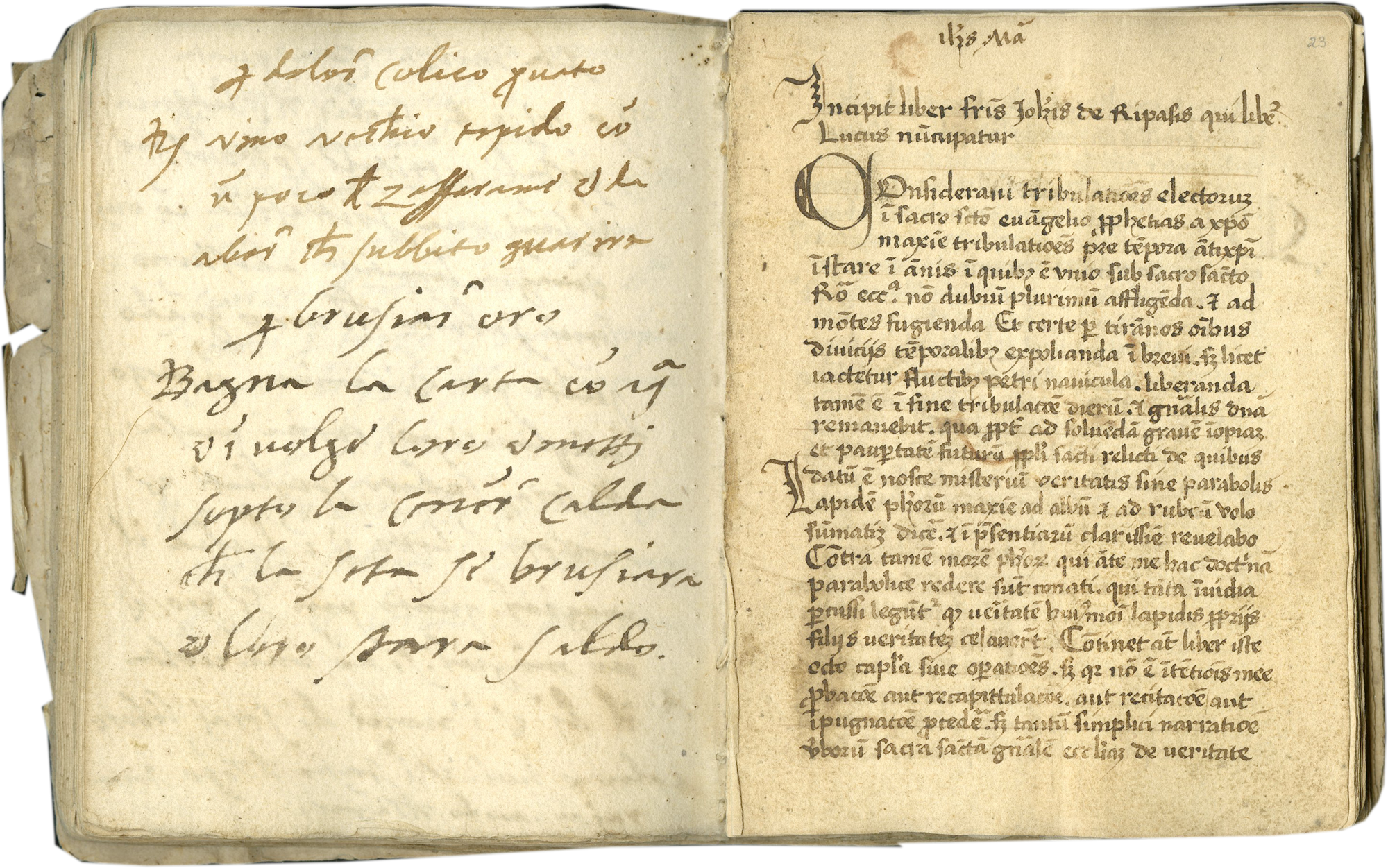

Beyond these recipes, though, this book contains something quite different at its core. The volume is made of a single, extremely large gathering of leaves (known as a quire, as discussed in this earlier post) enfolding two standard-sized quires at its center. These central pages contain an alchemical manual, the Liber lucis (Book of Light) of friar and alchemist John of Rupescissa, notorious in the Middle Ages for his apocalyptic prophecies and celebrated now as the father of modern medical chemistry. The Liber lucis specifically delineates a recipe for the philosophers’ stone, an alchemical substance thought to be capable of transmuting base metals into gold – and therefore very much in demand. (It was also considered useful for extending life, as popularized in the Harry Potter books and elsewhere.)

The opening page of the Liber lucis, nestled among later recipes, TM 843, ff. 22v-23

As you can see here, the Liber lucis was copied in a different, probably earlier hand. It shares the two added, central quires with alchemical recipes and extracts set down by the same person who copied the medical recipes that fill the rest of the volume, quite probably the person who assembled the book. This is a strange way to structure a manuscript. It has led us – and other scholars – to wonder, might the book’s compiler have been hiding these alchemical texts?

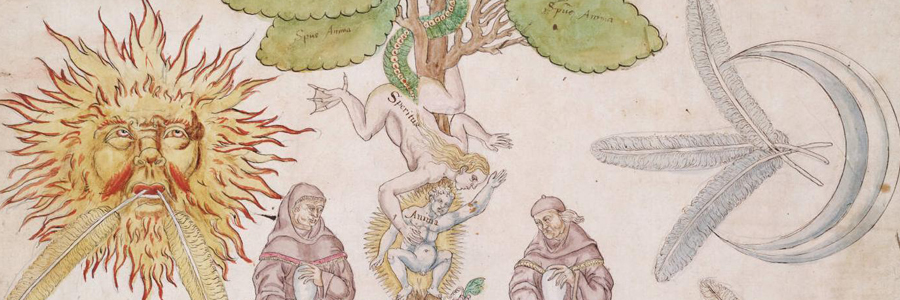

This symbolically dense alchemical scroll, one of the “Ripley” Scrolls, named for one of England’s most famous alchemists, employs esoteric alchemical emblems to represent the stages by which the philosphers’ stone was produced, New Haven, Beinecke Library, Mellon MS 41, England, c. 1570, details

In the sixteenth century, when this book was produced, alchemical texts and their writers embraced secrecy and concealment. Authors often wrote under pseudonyms, and alchemical texts encoded their secrets in allegory, emblematic imagery (as in the scroll above), and Christian symbolism. Perhaps our manuscript physically embodies this desire for secrecy, concealing its alchemical contents from casual discovery – or from censure.

Alchemists were a popular subject for critique in early modern art, where their dogged pursuits were dismissed as futile and materialistic or even ridiculed as foolish, as in this etching, “The Alchemist,” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, after 1558, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

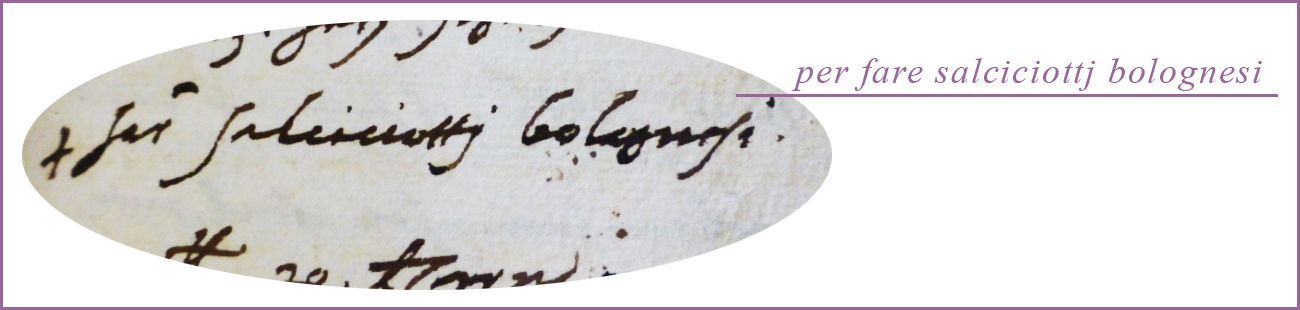

Alchemical secrets aren’t the only surprise awaiting the reader at the center of this book, though. Hiding in plain sight there is another witness to the interests of the book’s compiler: a recipe for ... Bolognese sausage.

This caption, "For making Bolognese sausage", alerts the attentive reader to the presence of one recipe that is not like its alchemical neighbors, TM 843, f. 41 (detail)

This is somewhat curious. It is not the only culinary recipe in the volume; a recipe for spiced wine appears, less surprisingly, among the medical recipes that fill the outer portions of the book. But why a sausage recipe here, where it is not even grouped with other recipes? Was the compiler in such a hurry to set it down that he or she copied it in the midst of this alchemical stint? Was it added later where there was available space? Perhaps the compiler felt this placement was fitting, that the knowledge and precision necessary to transmute metals would stand a sausage maker in good stead? Certainly, it must have been a prized recipe.

This book of secrets is one of more than thirty manuscripts featured in our latest exhibition, Traces: People and the Book , which is opening this week in our New York gallery. If you are in the area, we hope you will come and explore what manuscripts like this one can tell us about how they were made and used. You can also explore the show from afar in the exhibition catalogue, now available for purchase or download on our site.

Detail from woodcut depicting a kitchen scene, from a printed recipe book, Kuchemaistrey, Nuremberg, 1485

And, since it seems fitting that we should attempt one of the recipes in this book that abounds with them, watch this space for updates on our luck with the sausage recipe – we thought we might have better luck with that one than the philosophers’ stone.