Monsters and mythical creatures, birds and beasts, warriors and angels are far from unexpected in the margins of medieval manuscripts, where they supply endlessly variable subjects for marginalia.

These creatures inhabit the margins of three Books of Hours, BOH 136, ff. 45, 47 (details), Northern France (Rouen), c. 1490-1510; BOH 102, ff. 16, 31, 87 (details), France (Paris), c. 1490; and BOH 94, ff. 1v, 44 (details), Eastern Netherlands (probably Zwolle), c. 1470-1480

But they are far from marginal in this fascinating and phantasmagorical manuscript, which features a set of illustrated prophecies known as The Prophecies of the Popes. Here they occupy the center of the page and they hold far more meaning than meets the eye.

Cryptic prophecies and mottos occupy a small space beneath each of these enigmatic images in this copy of Vaticinia de summis pontificibus of Pseudo-Joachim of Fiore, ff. 2v-3; and 3v-4, Northern Italy and southeastern France (perhaps Savoy?), c. 1447-1455

Take the man on the left below, mounted on a white horse. Between his papal tiara and the inscription that names him as Pope Clement V, his intended identification is not in question. But what are we to make of the woman who stands behind him, framed in the doorway of a Gothic building? As hinted in the enigmatic text below the image, the prevailing contemporary interpretation of this prophecy held that it had foretold the Avignon Papacy (also known, more colorfully, as the “Babylonian Captivity”), the period from 1309 to 1377 in which seven successive popes took Avignon as their seat, not Rome. The woman (identified in the text as a widow) represents Rome. In effect, the mounted pope turns his back on the widow and leaves her, just as Clement V, the first of the seven Avignon popes, chose to leave Rome.

Clement V's abandonment of Rome for Avignon finds allegorical expression in this copy of Vaticinia, f. 4v

Made over a century after the events foretold by this "prophecy," however, this manuscript was not forecasting the future here but recalling the past. How can we explain the enduring appeal of this collection of prophecies? As an allegorical narrative, the pairing of word and image packs quite a punch, conveying the disruption and alienation people no doubt felt, say, when Clement left Rome for Avignon. These prophesies would by then also have provided a kind of history of the popes, different from but, perhaps, complementary to the more straightforward Short Catalogue of the Roman Popes (written by Dominican writer and inquisitor, Bernard Gui) which follows Prophecies in this manuscript. And from their origins in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, these papal prophecies served another decidedly non-prophetic purpose: they were written as a form of propaganda. As in so many medieval books of prophecies, these riddling predictions furnished a code, a means of concealing harsh political critiques so that not all could access them, and so that they could be denied.

John XXII is shown here wielding a scourge in one hand and the keys of St. Peter, symbol of his papal office, in the other, with a demon wearing a bishop's mitre off to one side, Vaticinia, f. 5

Drawing on a tradition that goes back to twelfth-century Byzantium, these prophecies took their present shape in the hands of the Spiritual Franciscans, vociferous advocates for poverty in the Church who were declared heretical for their attacks on the wealth of pope and clergy. Clement V’s successor Pope John XXII, shown above, was a particular thorn in the side of the Spirituals, excommunicating one of their leaders for heresy and condemning a group of Spirituals known as the Fraticelli. The Spirituals fought back against the pope and won a prominent ally in the Holy Roman Emperor, Louis IV, who then accused the pope of heresy. In the earliest versions of these prophecies, John is shown in a particularly negative light, wielding a scourge against a harmless, white dove, consistently used to represent the Franciscans throughout the prophecies. By the fifteenth century when our manuscript was produced, however, the significance of this image must have been lost or deliberately abandoned. Though John still wields a scourge here, he does not use it on anyone, dove or otherwise

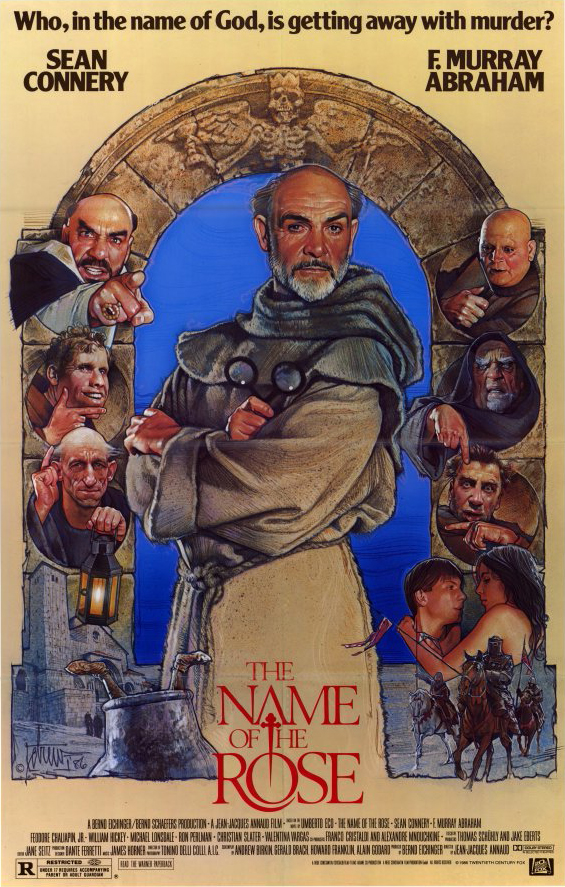

Bernard Gui is a villain in Umberto Eco’s Name of the Rose, as dramatically conveyed by F. Murray Abraham in the upper left corner of this theatrical poster for the film adaptation, Drew Struzan, 1986

If the names of Bernard Gui and the Fraticelli and the conflict between John and Louis sound familiar to you, we're guessing you may have some familiarity with the late Umberto Eco's celebrated novel, The Name of the Rose. The world Eco so richly evokes in that tale of mysterious manuscripts and murders – fraught with ecclesiastical conflict, heretical anxieties, and apocalyptic fears – is powerfully evoked in this intriguingly strange manuscript. And just as Eco's novel imagines a conflict of wits and worldviews between Gui, a well-known prosecutor of heretics, and several Franciscans (some historic, some fictional), so does this manuscript juxtapose Gui's vision of the papacy with that of the Spirituals.

The Beast of the Apocalypse is depicted here as a monstrous, winged, beast with the head of a man at one end and the head of a serpent at the other, Vaticinia, f. 8, detail

The novel's fascination with the apocalypse and its strange and powerful portents also resonate powerfully with this book of prophecies. One of the most enduringly popular images in the prophecies (and one of our favorites at Les Enluminures) is this monstrous Beast of the Apocalypse, whose handsome human face is rendered horrifying by his bewinged, bestial body, vulpine ears, and serpent-headed tail. Originally conceived as an apocalyptic endpoint for the prophecies, the beast was linked by the fifteenth century to another historic figure, Pope Urban VI, who presided over a period of violent schism in the Church. A century later, Protestants offered a new interpretation of this image, saying that it represented no pope in particular but the papacy in general.

This woodcut of the Beast of the Apocalypse appeared in a 1527 papal tract by Andreas Osiander and Hans Sachs, Eyn wunderliche Weyssagung von dem Babstumb, Nuremberg, Hans Guldenmundt

From their origins with the Spiritual Franciscans through their appropriation during the Protestant Reformation, the startling predictions and disturbing images that make up these prophecies allowed readers to see what they wanted or needed to see. With their shifting meanings and enduring mysteries, this text has remained an abiding source of fascination.

Come see it for yourself this week at the New York Antiquarian Book Fair! We will be displaying it at our booth from 9 to 12 March, along with a selection of other strange and beautiful manuscripts.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”