This post takes a closer look at what’s in a Book of Hours, which is arguably the most important text of the late Middle Ages. This is why. If we are ever to understand social history of any period, we must go to what was known and used by the largest number of people at that time. One could claim that the Divine Comedy or the Roman de la Rose or Beowulf were the greatest medieval texts, and one might be right, but ultimately these were part of the experience of only a tiny percentage of the population.

BOH 140, The Saxby Psalter-Hours (use of Sarum), England, probably London, c. 1425-40, ff. 7v-8, Annunciation

The Book of Hours, however, was the first text read all across Europe by all people at every level of literacy. Its words reached an enormous audience, more than any written text had ever done. It was the book from which medieval children were taught to read. It was a text which most people knew by heart. Its phases were the most familiar usage of the Latin language for several centuries. Extraordinarily, although the more famous literary monuments have been published thousands of times, there is still no modern critical edition of the text of the Book of Hours. It would be an invaluable publication for the study of language and daily life, and as a record of the aspirations and fears of everyday people.

BOH 126, Villeneuve Hours, Belgium, Bruges, c. 1450, f. 53, Annunciation (detail)

BOH 110, Prayer Book, Belgium, Brussels, c. 1460 and Lille, c. 1475, f. 198 and f. 220v, Virgin seated with a book; Virgin under a baldachin (details)

The historian Eamon Duffy has famously said that the history of prayer is as important and as difficult to document as the history of sex, and for many of the same reasons. The Book of Hours brings us directly into the mindset and intimate thought process of a medieval person. They are very private and personal. The prayers on death, plague, warfare, travel and bad weather, all found in Books of Hours, touch us with a vividness that no literary text can ever evoke.

BOH 3, Circle of Etienne Collault, France, Paris or the Loire Valley (Tours?), c. 1525, f. 13v . Annunciation (detail)

To understand the Hours of the Virgin one must go back to the medieval understanding of the Annunciation. Around the year 0, the archangel Gabriel appeared to an ordinary woman in Nazareth to tell her that she had found ultimate favour with God. Implicitly, every Christian woman since that moment aspired to such supreme perfection. What was the Virgin Mary doing at that precise holy instant? According to medieval tradition, she was interrupted while kneeling in private, reading passages from the Old Testament in a prayer book. She is shown doing precisely that in the picture for Matins in almost every Book of Hours.

BOH 141, Book of Hours With 7 inserted full-page miniatures by the Assumption Master, with borders and initials by the Monkey Master, The Netherlands (South Holland), c. 1485-90., ff.13v-14, Annunciation

Books of Hours were probably mostly used by women. The texts of the Hours of the Virgin were made up almost entirely from the words of the Bible which Mary could actually have been reading and thinking about. Probably 85% of the text is extracted directly from the Bible. It comprises psalms and quotations from the Old Testament prophets, interspersed with the words with which the Virgin was interrupted, “Hail, Mary” and “Blessed art thou among women.” In reading these texts, a devout medieval woman recreated for herself the identical experience of the Virgin Mary, opening herself to divine favour.

BOH 118, Book of Hours (Use of Rome) with 13 large miniatures from the Workshop of Willem Vrelant, Southern Netherlands, Bruges (Ghistelles?), c.1460s, f. 28, Virgin and Child Enthroned.

The Hours of the Cross in a Book of Hours were similarly devised to help evoke the experience of the final day before the death of Christ. Any Christian man was encouraged to imagine suffering the torments of Christ himself, but a woman too was taught to imagine watching the Crucifixion. The Virgin, attended by Saint John, appears in nearly every picture of Christ on the Cross. This is why pictures of the Annunciation and the Crucifixion are the two most common images in all of medieval art and in every Book of Hours.

BOH 126, Villeneuve Hours, Belgium, Bruges, c. 1450, f. 33, Crucifixion (detail)

The Seven Penitential Psalms in a Book of Hours were reputedly written by King David in remorse for having committed every one of the seven Deadly Sins. Again, this is a text taken directly from the Old Testament. In reading them devoutly, the owner of a Book of Hours was repeating the exact words used by David, who was ultimately restored to God’s favour.

BOH 60, Printed Book of Hours (Use of Rome), France, Paris, c. 1526 [almanac 1526-1541], sig. F8, David observing Bathsheba Bathing (Pichore Workshop for Eustace, in-8°, c. 1508)

The Office of the Dead was a reminder of the imminence and unpredictability of death. The most substantial parts of its text are taken from the book of Job, also in the Old Testament. Every imaginable disaster happened to Job and yet he endured and came through; and in reading the text the medieval owner of the manuscript shared that experience of humanity with humility and patience. Probably quite literally millions of people had their lives and outlooks on life affected by these ancient texts.

BOH 142, Hours of Philippote de Nanterre (Use of Amiens), France, Amiens, c. 1420s , ff. 158v-159, Funeral Service (detail)

Most collectors now regard Books of Hours exclusively as picture-books by illuminators, but in actually reading the text and looking at the images we are transported into the presence and into the most intimate thoughts of men and women (especially) of five hundred years ago.

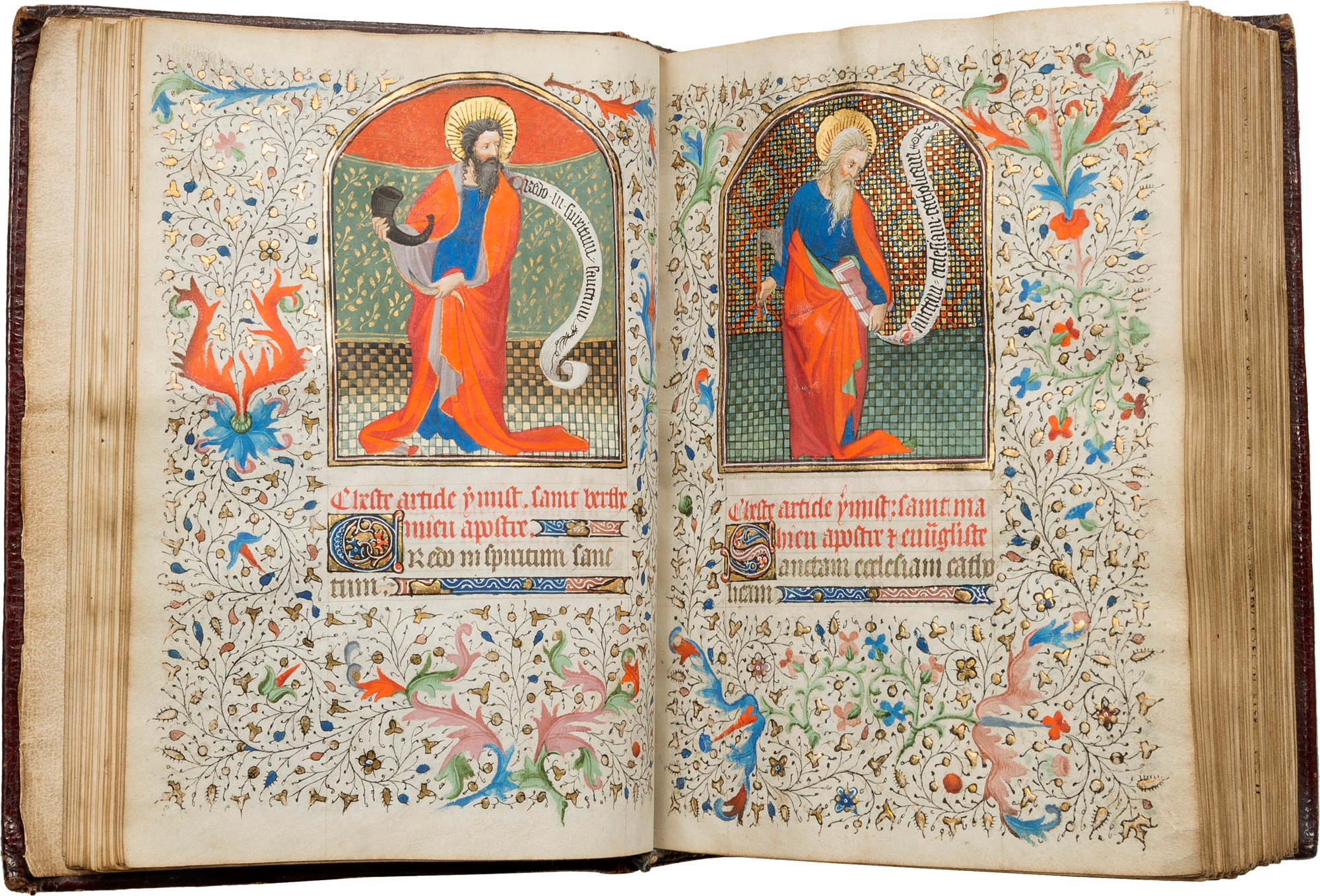

BOH 142, Hours of Philippote de Nanterre (Use of Amiens), France, Amiens, c. 1420s , ff. 20v-21, Philip and Bartholomew

BOH 142, Hours of Philippote de Nanterre (Use of Amiens), France, Amiens, c. 1420s , f18, James the Great (detail)

See a selection of our Books of Hours by clicking here.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”