The text manuscripts featured on this blog so far range in their contents from the rare or unique to works that would have been circulated and valued within particular circles (astrologers, say, or the French court) in the medieval and early modern world. But if you want a sense of the kind of book owned and read most widely in the Middle Ages, you need look no further than the Book of Hours.

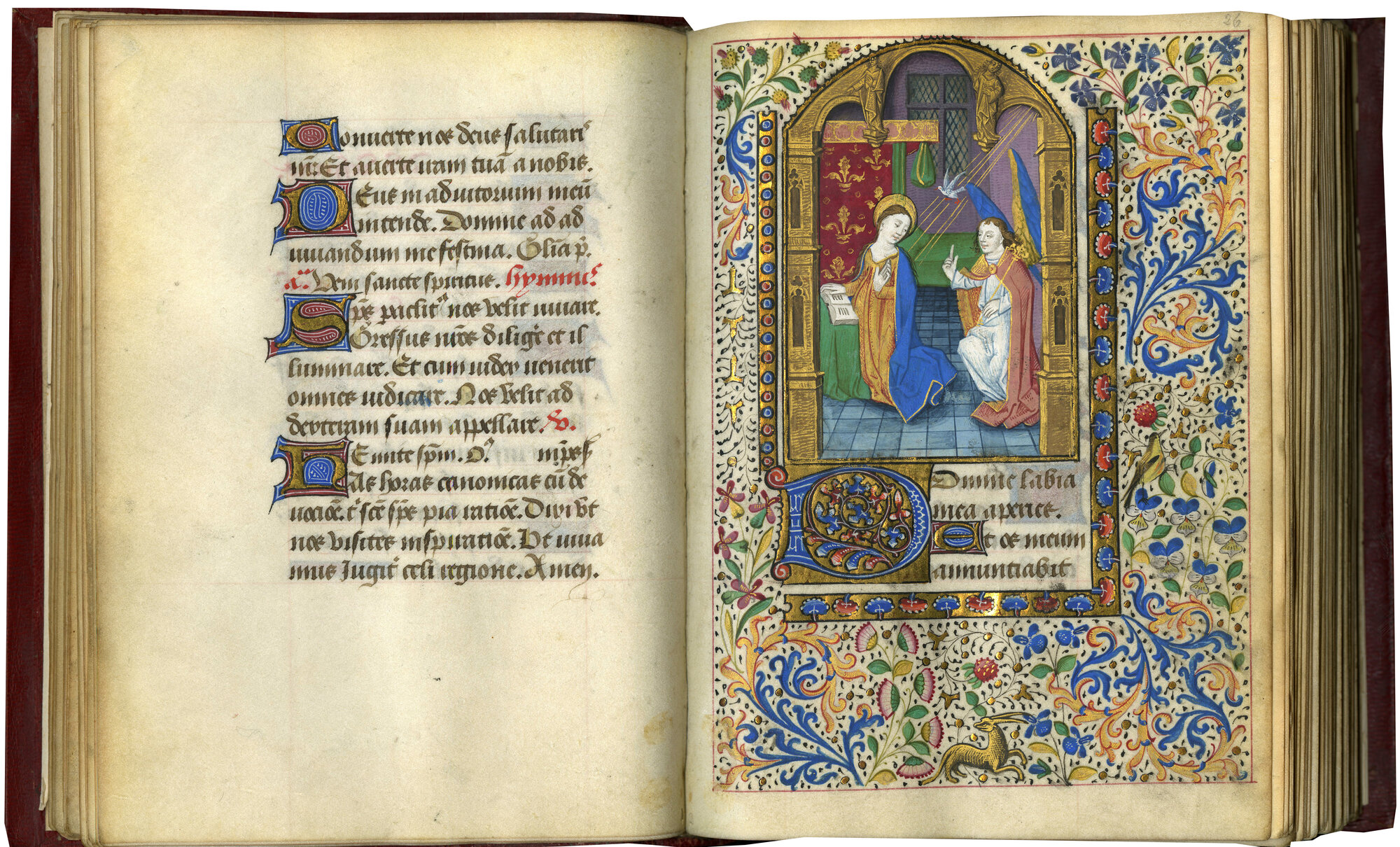

Delicate sprays of leaves and flowers frame this vivid Annunciation miniature, painted by an artist from the circle of the Master of the Troyes Missal to mark the beginning of the Hours of the Virgin, Book of Hours (Use of Troyes), BOH 131, France (Troyes), 1460-1470, ff. 25v-26

Delicate sprays of leaves and flowers frame this vivid Annunciation miniature, painted by an artist from the circle of the Master of the Troyes Missal to mark the beginning of the Hours of the Virgin, Book of Hours (Use of Troyes), BOH 131, France (Troyes), 1460-1470, ff. 25v-26

Generally small in size and attractively, even lavishly, illustrated, Books of Hours were chiefly made for the use of lay people, not for priests or monks. Their contents could be tailored somewhat to the devotions and desires of a particular buyer, but nearly all Books of Hours contain the Hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a set of prayers to be said throughout the day at eight canonical hours: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. One wonders how many lay people prayed all (or, indeed, any) of these hours, but we do encounter accounts of them doing so – some Books of Hours even contain paintings of their owners praying with book in hand!

This charming miniature of Saint Anne teaching the young Virgin Mary how to read, painted by Guillaume II Le Roy, demonstrates one of the other important ways in which lay families used their Books of Hours (Use of Rome), BOH 46, France, Lyons, c. 1495-1510, f. 187v (detail)

This regular and (at least in theory) regimented routine of daily prayer originated in monastic practice. Monks and nuns were required by the Rules of their orders to pray the canonical hours every day, known as the Divine Office. Many surviving monastic liturgical manuscripts were dedicated to this endeavor. Books of Hours derive texts like the Hours of the Virgin from books like this Breviary (shown below), which brought together all of the prayers and other texts a monastic would need to pray the Divine Office.

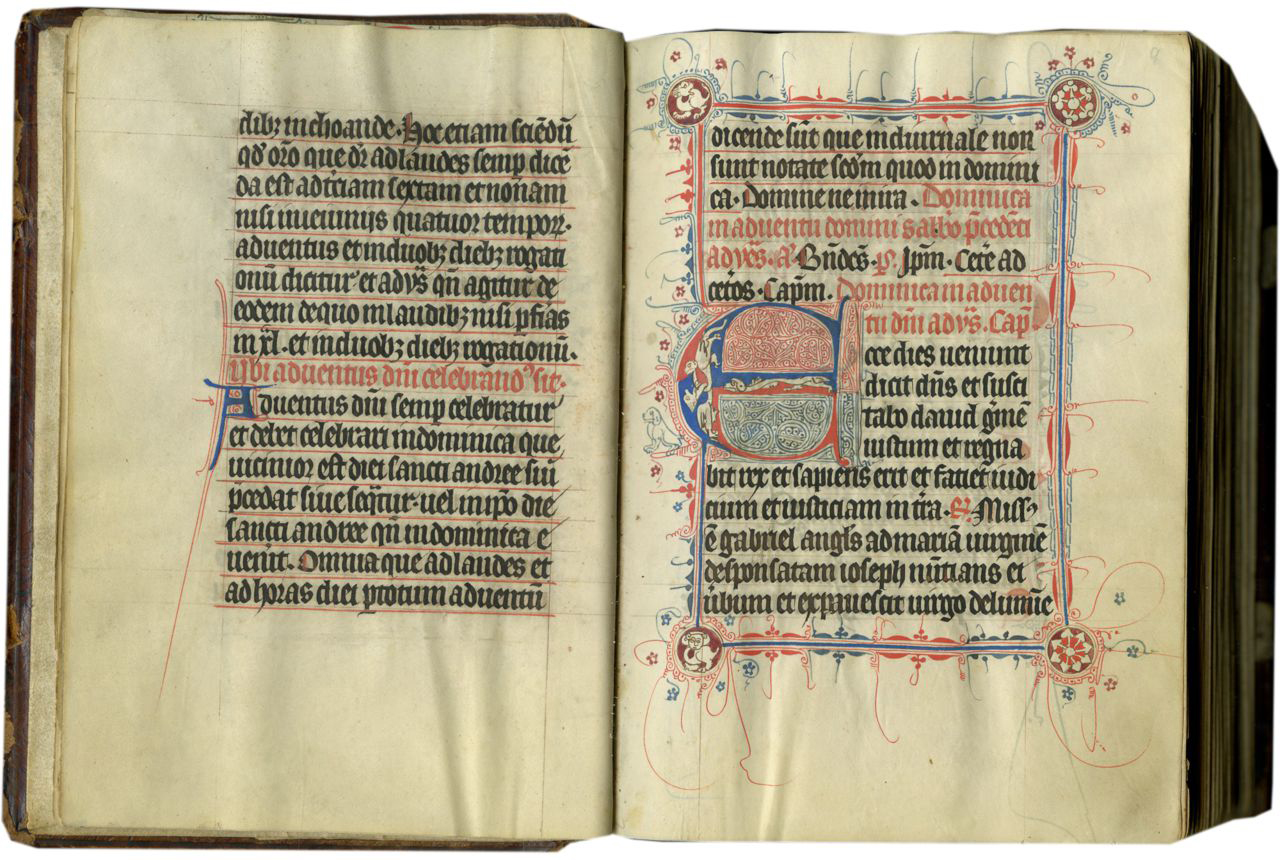

This Breviary, made for the use of Dominican friar or nun, also contains the Hours of the Virgin, along with other prayers, psalms, and short texts to be read at the canonical hours, Diurnal (Dominican Use), TM 835, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland, possibly Strasbourg), c. 1300-1320 (probably c. 1302-1307), with later fourteenth- and fifteenth-century additions, ff. 8v-9

This Breviary, made for the use of Dominican friar or nun, also contains the Hours of the Virgin, along with other prayers, psalms, and short texts to be read at the canonical hours, Diurnal (Dominican Use), TM 835, Southern Germany or Alsace (Upper Rhineland, possibly Strasbourg), c. 1300-1320 (probably c. 1302-1307), with later fourteenth- and fifteenth-century additions, ff. 8v-9

Whether they wanted Books of Hours as prayerbooks, rich in spiritually beneficial contents, or as status objects, resplendent with beautiful paintings, an unprecedented number of people desired and valued these books in the late Middle Ages and beyond. Deluxe Books of Hours were painted by the best artists of the day as one-of-a-kind art objects tailored to the tastes of the buyer, and you might find a dozen of these in the library of a wealthy aristocratic collector (think Jean, Duc de Berry and his Très Riches Heures. At the other end of the spectrum, commercial booksellers produced Books of Hours in massive quantity to satisfy the demand of well-to-do families, many of which may not have owned any other books.

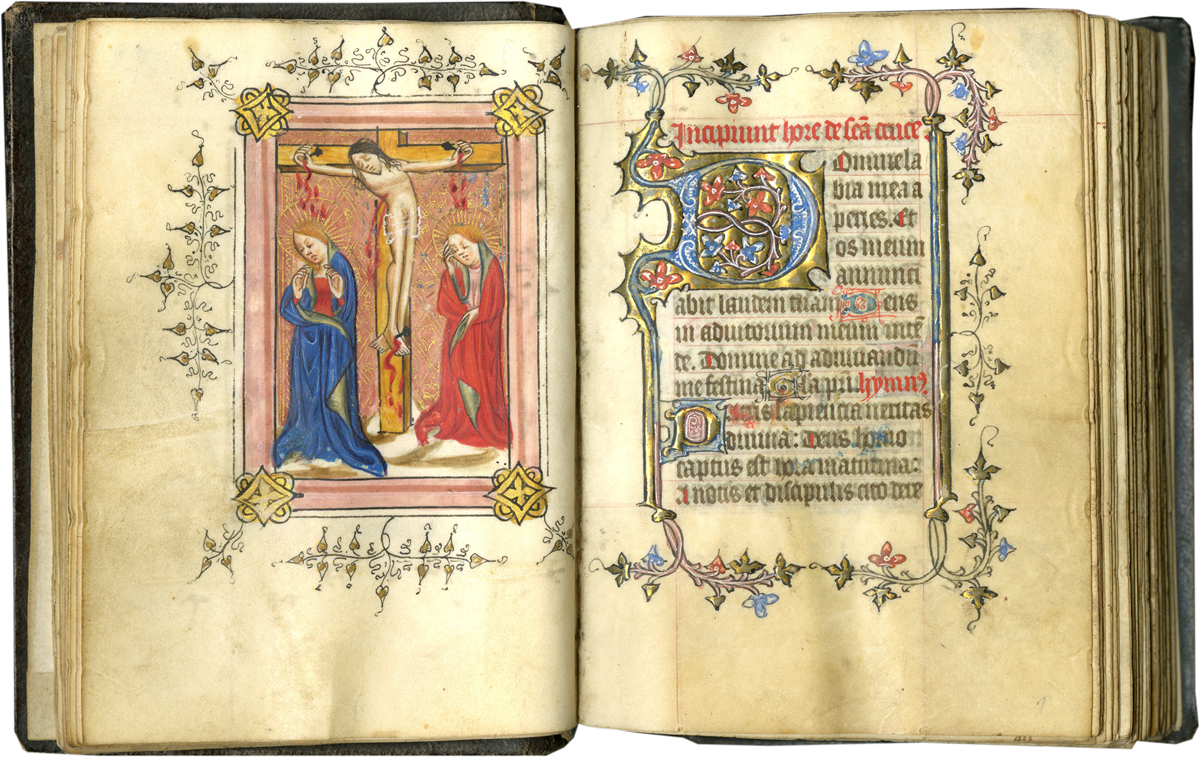

Notice the different decorative styles in the border of the Crucifixion miniature on the left and the opening of the Hours of the Cross on the right in this delicate Book of Hours (Use of Rome), BOH 130, Belgium (Bruges), 1400-1410, ff. 27v-28

Notice the different decorative styles in the border of the Crucifixion miniature on the left and the opening of the Hours of the Cross on the right in this delicate Book of Hours (Use of Rome), BOH 130, Belgium (Bruges), 1400-1410, ff. 27v-28

In that latter vein, this Book of Hours here was not created for a particular buyer. Instead, it was made on-spec in Bruges, a major producer and exporter of Books of Hours in the fifteenth century. The miniature on the left was produced independently of the rest of the book. The book’s buyer could have bought this handsomely illuminated Book of Hours without pictures, but he or she had the funds to upgrade it, and so accordingly purchased five miniatures and had them inserted into their appropriate places in the book.

Popular demand for Books of Hours carried over into print, as these two sixteenth-century books illustrate:

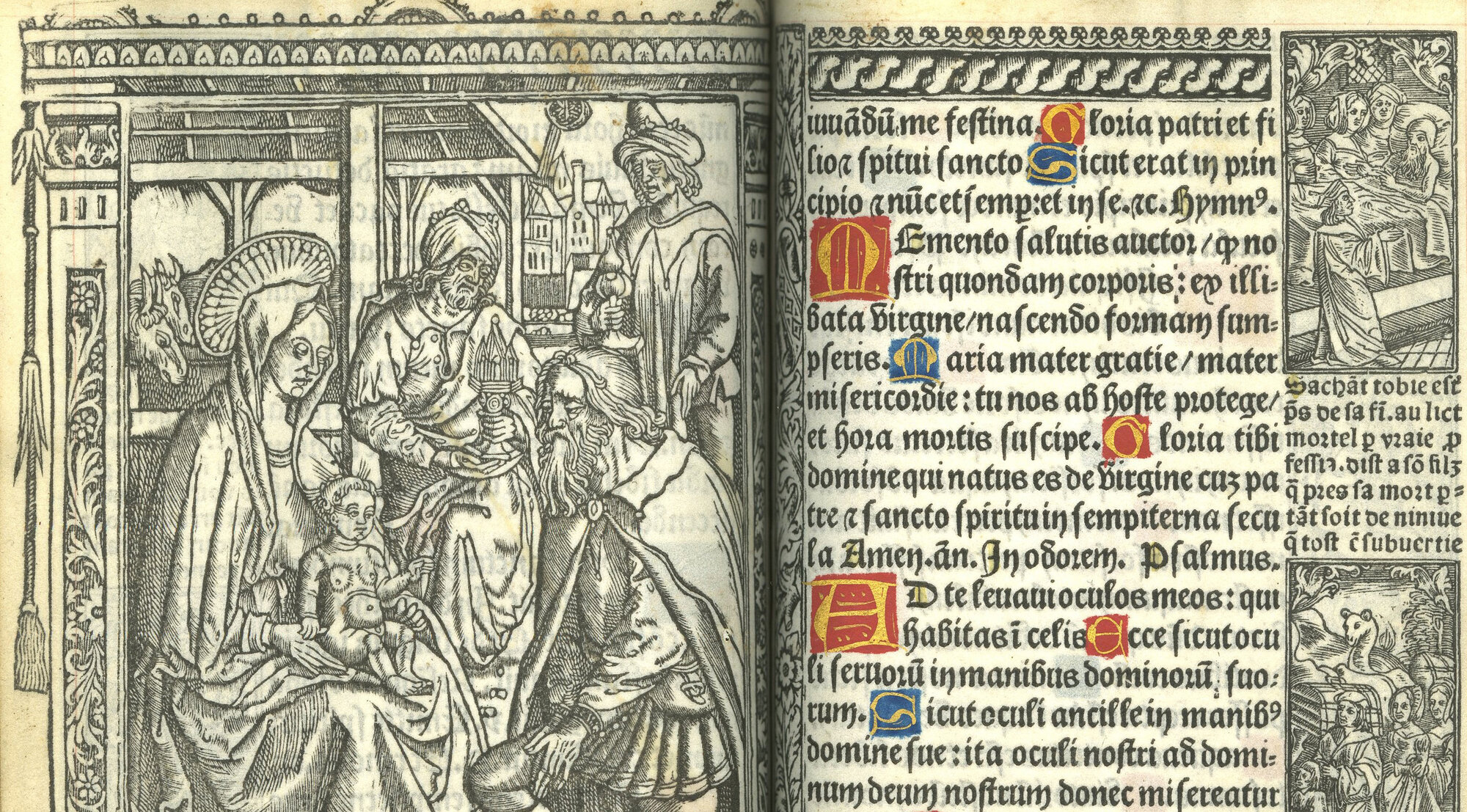

Painted initials persist in this early printed Book of Hours, with metalcuts of the Adoration of the Magi and scenes from the Book of Tobit following designs by two well-known illuminators, the Master of the Très Petites Heures of Anne of Brittany and Jean Pichore, Printed Book of Hours (Use of Rome), BOH 75, Paris, Simon Vostre, c. 1515, sig. H3v-H4r

Painted initials persist in this early printed Book of Hours, with metalcuts of the Adoration of the Magi and scenes from the Book of Tobit following designs by two well-known illuminators, the Master of the Très Petites Heures of Anne of Brittany and Jean Pichore, Printed Book of Hours (Use of Rome), BOH 75, Paris, Simon Vostre, c. 1515, sig. H3v-H4r

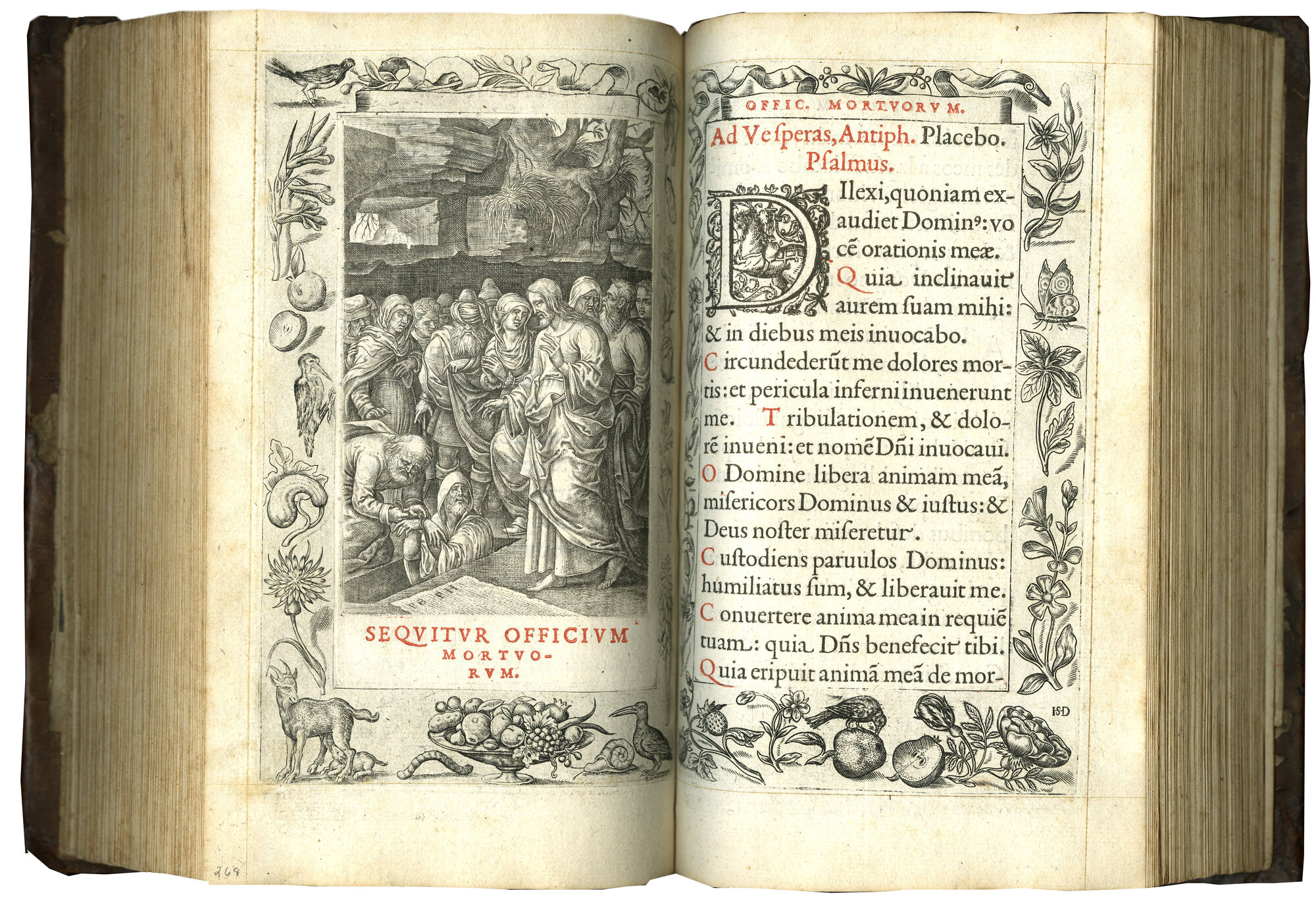

Surrounded by a border thronging with life, Jesus is shown raising Lazarus from the dead in this engraving, signed by Peeter van der Borcht and Pieter Huys, in this deluxe printed Book of Hours (Use of Rome), BOH 109, Antwerp, Christopher Plantin, 1570, sig. K6v-K7r

Surrounded by a border thronging with life, Jesus is shown raising Lazarus from the dead in this engraving, signed by Peeter van der Borcht and Pieter Huys, in this deluxe printed Book of Hours (Use of Rome), BOH 109, Antwerp, Christopher Plantin, 1570, sig. K6v-K7r

And then there’s this much later book of prayers, produced in an era of renewed fascination with the culture, arts, and aesthetics of the Middle Ages:

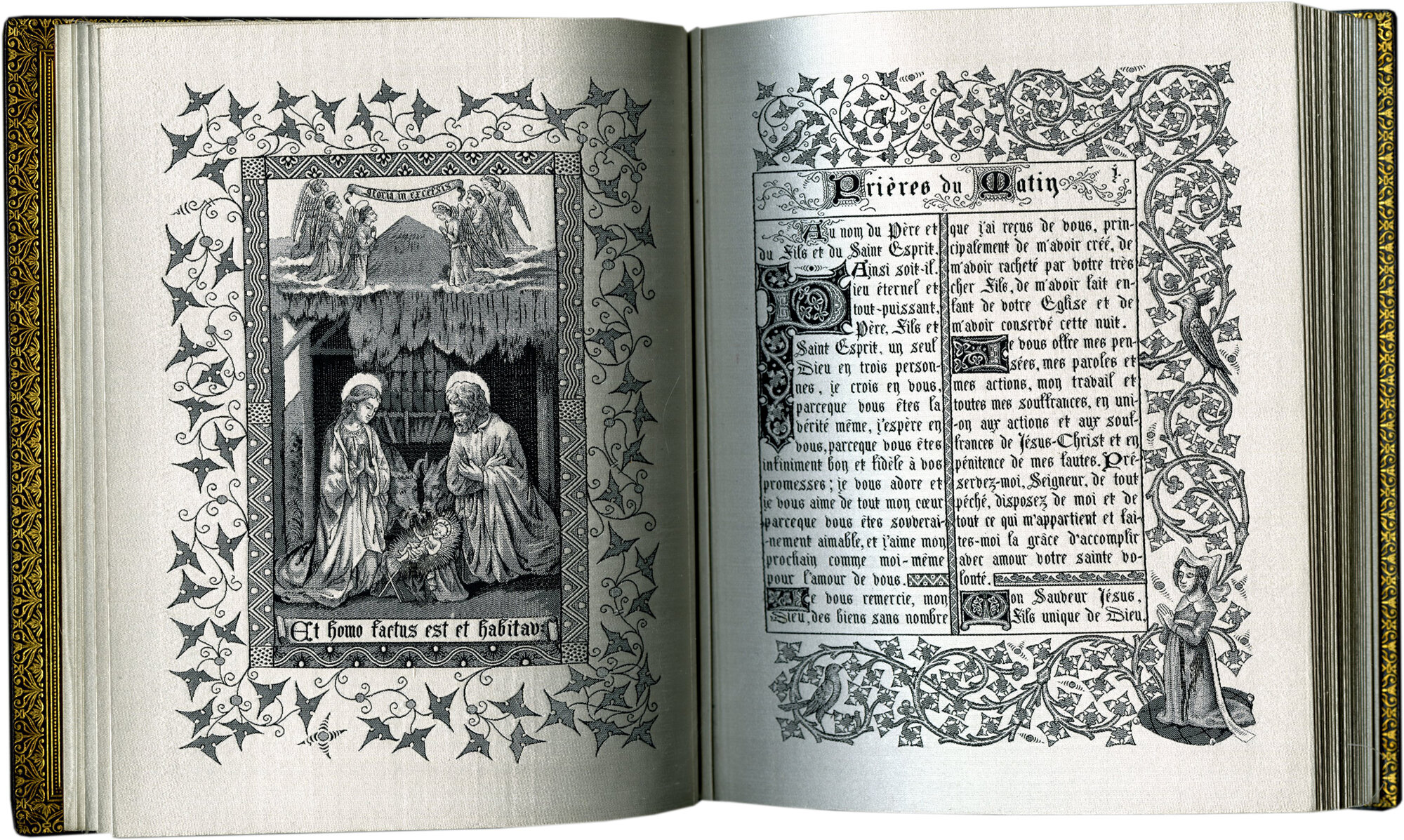

Executed entirely in woven black and silver silk thread on a machine loom, this book’s Nativity miniature and leafy borders very deliberately recall the look of a medieval Book of Hours, Livre de Prières Tissé, BOH 86, Lyon, R. P. J. Hervier, designer; J. A. Henry, fabricator; for A. Roux, 1886-1887, pp. ix-1

Executed entirely in woven black and silver silk thread on a machine loom, this book’s Nativity miniature and leafy borders very deliberately recall the look of a medieval Book of Hours, Livre de Prières Tissé, BOH 86, Lyon, R. P. J. Hervier, designer; J. A. Henry, fabricator; for A. Roux, 1886-1887, pp. ix-1

The very old and the very new marry gracefully in this delicate volume, the only illustrated book ever successfully woven on a machine loom. Specifically, it was made using the punched-card system of the Jacquard looms, which was a primary inspiration for the Analytical Engine of computer pioneer Charles Babbage (1791-1871). Though this book production technique never caught on, it seems oddly appropriate that this prayerbook, so indebted in many respects to the medieval Book of Hours, should have been made in this simultaneously modern and luxurious medium.

Check out these and other Books of Hours on our Books of Hours site, just updated with new inventory.