Aside from the prodigious quantity of snow it deposited on the American East Coast, one of the most notable stories about the recent Winter Storm Jonas was that meteorologists had been able to predict it early and accurately. But we can probably all conjure up a big storm in recent memory that took us by surprise – in its sudden onslaught or in its total failure to materialize.

Sailors face death in a tempest at sea in this woodcut from Hans Holbein the Younger’s Danse Macabre, 1523-1526

Sailors face death in a tempest at sea in this woodcut from Hans Holbein the Younger’s Danse Macabre, 1523-1526

Weather prediction has a long history, and for good reason, when you consider the repercussions to human lives and best-laid plans, and to buildings and crops that a bad storm can have even now – and would certainly have had in pre-industrial times. As early as the seventh century BC, we know that the Babylonians attempted short-term weather prediction based on what they observed in the sky. Around 340 BC the Greek philosopher Aristotle formulated theories regarding the causes of thunder and lightning and other weather phenomena in the treatise, Meteorologica.

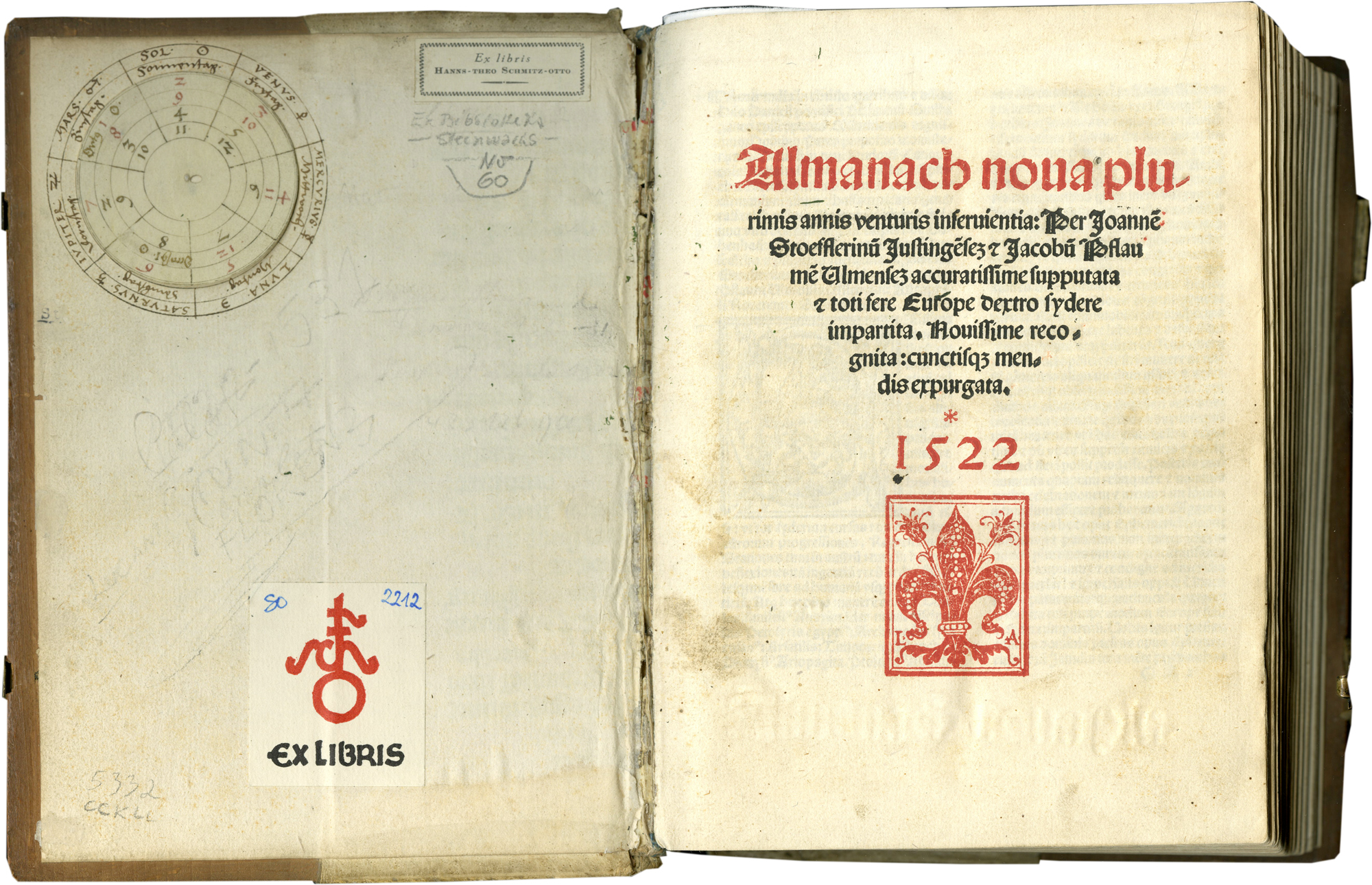

The initial opening of a printed almanac, Johannes Stöffler and Jacob Pflaum’s Almanach nova plurimis annis venturis inservientia, with its title page, TM 850, printed in Venice by Lucantonio Giunta, 1522, front pastedown and sig. A1 recto

At the dawn of the Age of Discovery, people looked to the heavens to predict the weather. This fascinating almanac, featured in our recent Text Manuscripts update, contains calculations (covering a period of nine years!) of the daily positions of the seven ‘planets’ known and scrutinized by medieval astrologers – Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the sun, Venus, Mercury, and the moon. And what was the discerning reader to do with these tables and tables of calculations? Make meteorological predictions, among other things.

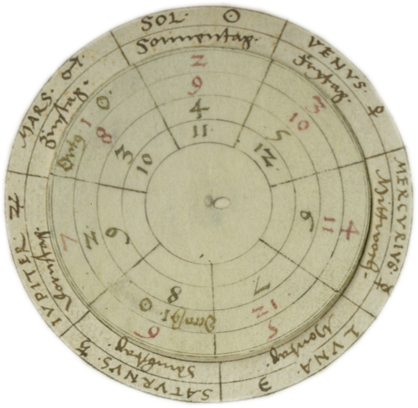

You can see the planets and their signs identified in the outermost field of this working volvelle, a kind of proto-computer, which was added by the book’s early owner and would have allowed him to quickly determine which planet ruled over every hour of every day of the week, TM 850, front pastedown (detail)

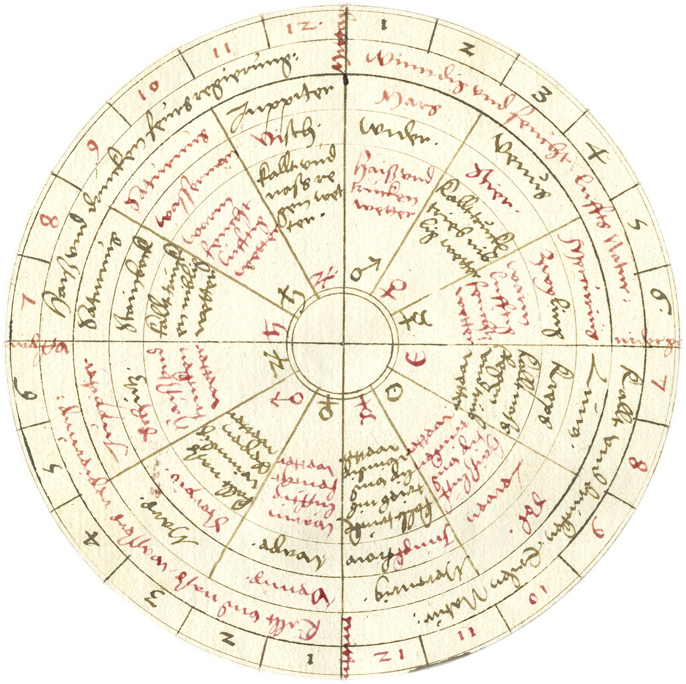

In fact, we know the book was used this way. This volume’s earliest owner customized it with many additions. Chief among them are extensive notes in German that explain how to forecast the weather using the almanac’s tables. The book’s owner even drew a complex weather diagram, shown below, enabling him and later users to draw correspondences between planetary influence and weather conditions.

Also added by this early owner, the weather diagram shown here traces correspondences between the hours of the day, the four classical elements, the seven planets, the signs of the zodiac, and particular weather conditions, TM 850, f. i verso (detail)

Why the owner’s interest in the weather? For one thing, this almanac’s publication had triggered a sensation by this time. The almanac’s authors, Johannes Stöffler and Jacob Pflaum, having calculated sixteen planetary conjunctions in the watery sign of Pisces for February of 1524, shared their conclusion that these conjunctions would bring about a period of drastic, unprecedented change. Their conclusions, too vague in their own right to provoke alarm, were given more terrifying shape early in the sixteenth-century by a prominent Italian astrologer, Luca Gaurico, who predicted that the coming conjunctions would cause a catastrophic flood, along with a number of correspondingly apocalyptic events, like massive earthquakes, deadly epidemics, and the arrival of a false prophet.

Pisces, marked with a figure of death, looms over a scene of flooding and strife in this title page for a pamphlet advertising the apocalyptic events predicted for 1524, Leonard Reynmann’s Practica vber die grossen vnd manigfaltigen Coniunction der Planeten, printed in Nuremberg by Hieronymus Höltzel in 1523

These predictions generated an early modern media frenzy. While astrologers argued amongst themselves about the flood prediction (Stöffler, notably, argued against it), some also circulated pamphlets proclaiming the imminent disasters and featuring woodcuts depicting these catastrophes in ghastly detail, as in the pamphlet shown above. Flood panic swept Europe. Preachers declared the flood a sign of God’s wrath. People relocated in an effort to survive the coming deluge. In fact, a president of the parliament of Toulouse even took a page from the Bible, building an ark upon a mountaintop in preparation for the disaster!

One of Leonardo’s ‘deluge’ drawings, quite possibly inspired by the widespread panic and controversy over the flood predicted for 1524, Leonardo da Vinci, A deluge, c. 1517-c. 1518, Royal Collection Trust

When February of 1524 arrived, of course, the weather was completely uneventful. No floods wrought destruction on Europe, and we may imagine the parliamentarian of Toulouse rather ruefully abandoned his ark to resume normal life. Critics of astrology, like Martin Luther, ridiculed astrologers for the failed prophecy. And yet astrology retained its authority well into the seventeenth century, as people continued to seek their futures – meteorological or otherwise – in the stars.

You can read more about this fascinating almanac here.