Happy New Year to all of our readers! The year 2017 is full of possibilities – and, we’re guessing, full of resolutions as well. Perhaps you already anticipate scrapping all of these commitments after a few weeks of enthusiastic effort or maybe you have devised some strategies for long-term resolution-keeping (in which case, we say, how do you do it?!). Either way, you’re part of a much larger tradition of self-scrutiny, self-improvement, and – because we’re all human – some inevitable frailties along the way.

A delicate painting of King David graces the opening of this Ferial Psalter, TM 874 , ff. 1v-2, Northern Italy (Liguria or Lombardy), c. 1487

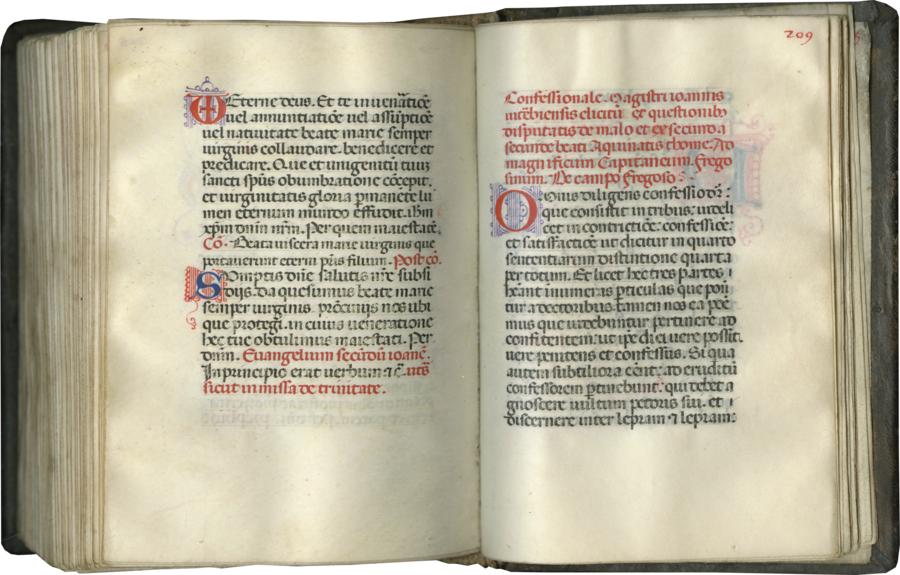

This manuscript is a perfect case in point. A luxurious Psalter, it presents its devotional contents – Psalms, hymns, prayers, and so on – amid brilliant illumination and graceful adornments, adding considerable aesthetic appeal to the practice of daily prayer. One final text at the back of the book, a confessional manual, maintains the book’s general orientation towards spiritual well-being, while also offering a more specific roadmap towards inner reform. And yet a little investigation of the origins of this unique work reveals two fascinatingly flawed figures connected to its creation, prompting us to ask what motives lay behind this particular instrument for self-improvement.

The Seven Deadly Sins – pride, wrath, lust, sloth, greed, envy, and gluttony – are embodied in these figures, illustrating a copy of the Testament of Jean de Meun, London, British Library, Yates Thompson MS 21, f. 65 (detail)

Confessional manuals abounded in the late Middle Ages. Many of these were written as guides for a confessor – that is, a priest or friar administering confession – to help him be as thorough as possible. These were painstakingly structured texts, typically organized around the Seven Deadly Sins, the Ten Commandments, and even the social rank or occupation of the person confessing. Each of these divisions prompted confessors with useful questions they might ask to aid people in their confessions. For example, Raymond of Peñafort’s influential manual Summa de poenitentia suggests that the confessor ask princes if they had ever withheld justice and that he ask knights if they had ever used their power and position to pillage.

A confessor hears a penitent’s confession in James Le Palmer’s Omne Bonum, London, British Library, Royal MS 6.E.vi, f. 354v (detail)

Other confessional manuals directly address the person preparing to confess his or her sins – and our manual is one of these. Like confessors’ manuals, it uses the structure of the Seven Deadly Sins and Ten Commandments to help the penitent discern, repent, and confess his or her sins. For a reader looking to turn over a new leaf, this would have offered a very thorough path forward.

The opening of the Confessionale of Annius of Viterbo, TM 874, f. 209

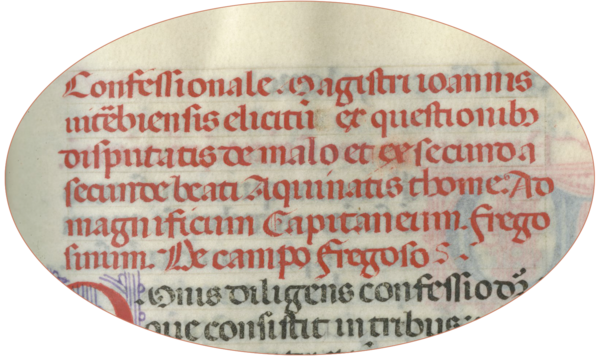

And, in fact, we know who read this text – or at least who was meant to read it. Its opening rubric, enlarged below, identifies both an author, one Johannes Viterbiensis, and a dedicatee, a “magnificent captain” Fregoso. Some quick research reveals that Johannes Viterbiensis was a Dominican scholar and historian better known as Giovanni Nanni or Annius of Viterbo (1432-1502). The Fregoso, or Campofregoso, family was a powerful and prominent Genoese family during this time, but which Fregoso could Annius have had in mind? As it turns out, one Paolo Fregoso (1427-1498) offered Annius his patronage while the friar was teaching and preaching in Genoa (between 1471 and 1489). Furthermore, in addition to holding ecclesiastical and political office as Archbishop of Genoa (1453-1495) and three-time doge of Genoa (May 1462, 1463-1464, 1483-1488), Paolo Fregoso served as an admiral of the papal fleet in the siege of Otranto (1481), thus meriting Annius’s flattering epithet, “magnificent captain” (and allowing us to hazard that this text was written around or after 1481!).

This Latin inscription identifies the text that follows as the “Confessionale of Master Johannes Viterbiensis ... to the magnificent Captain Fregoso, de Campofregoso,” TM 874, f. 209 (detail)

As the outline of his career suggests, Paolo Fregoso led a very interesting life, to say the least. Appointed to the archbishopric at a young age, he then squabbled over the dogeship of Genoa with his cousin and, having secured it, he allowed corruption and confusion to flourish in the city-state. After being expelled from that position in 1464, Fregoso set to sea as a pirate, a career for which he demonstrated considerable flair. And even his fall from grace seems to have left him unchastened; upon his return to Genoa in the 1480s, he was again forced out of the city in 1488, this time by popular rebellion.

A nineteenth-century Genoese artist’s depiction of Paolo Fregoso, Genoa, Gallery of Palazzo Bianco

Annius might have hoped his confessional manual would help Fregoso atone for his checkered past – or perhaps his motives were more self-interested. This is the only copy of the text that survives and it is a deluxe volume designed for personal use, judging from its small size. Furthermore, the inclusion of several local Genoese saints in the calendar strongly indicates that the book was made to be used in Genoa. Produced around 1487, during the relatively small window of time in which Annius could have written his confessional manual for Fregoso, this manuscript may well have been Annius’s presentation copy, a gift for his generous patron and a means of securing his continued favor.

The front and back of a ducat of Paolo Fregoso, coined between 1483 and 1488

If the dedication had its desired effect, Annius did not have long to enjoy it. The year after Fregoso was expelled from Genoa, he left as well after falling afoul of the Dominican hierarchy. Taking some inspiration from his Genoese patron, perhaps, he embarked on a personal reinvention of his own, becoming a very successful forger of antiquities. After leaving Genoa, he returned to Viterbo, which he attempted to establish as a political and cultural center of the ancient world with the help of staged excavations, seeded with false artifacts, and histories forged in the names of ancient authors. It is for this later career that he is now best remembered.

So give yourself a reassuring pat on the back. By these standards, none of us is doing all that badly with our New Year’s resolutions!

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”