He prophesied a “Sword of of the Lord” poised over the earth. He oversaw the immolation of great works of art and literature in so-called bonfires of the vanities. He brought down the Medici and defied the pope. He was challenged to a trial by fire. No matter what we might think of preacher and firebrand Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498), his message, or his methods, it’s undeniable that he led an extraordinary life.

Girolamo Savonarola, painted in profile by Fra Bartolomeo, c. 1497-1498, Florence, Museo di San Marco, Florence

Girolamo Savonarola, painted in profile by Fra Bartolomeo, c. 1497-1498, Florence, Museo di San Marco, Florence

His death was similarly sensational. Savonarola lost a great deal of popular support after one of his followers agreed to represent him in the proposed trial by fire, which was then delayed and finally canceled. Enraged by Savonarola’s failure to deliver a miracle – a feat of which many believed him capable – an angry mob assaulted the Dominican convent to which he belonged.

An early depiction of Savonarola’s public hanging and burning in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence in 1498, attributed to Francesco di Lorenzo Rosselli, Florence, Museo di San Marco

An early depiction of Savonarola’s public hanging and burning in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence in 1498, attributed to Francesco di Lorenzo Rosselli, Florence, Museo di San Marco

Savonarola was arrested on charges of sedition and uttering false prophecies and imprisoned for over a month. By the permission of the pope, Savonarola was tortured until he confessed his guilt, only to deny it and confess it again. Still, as he awaited his impending execution – Savonarola and two of his followers would first be hanged and then burned on 23 May 1498 – he was not idle.

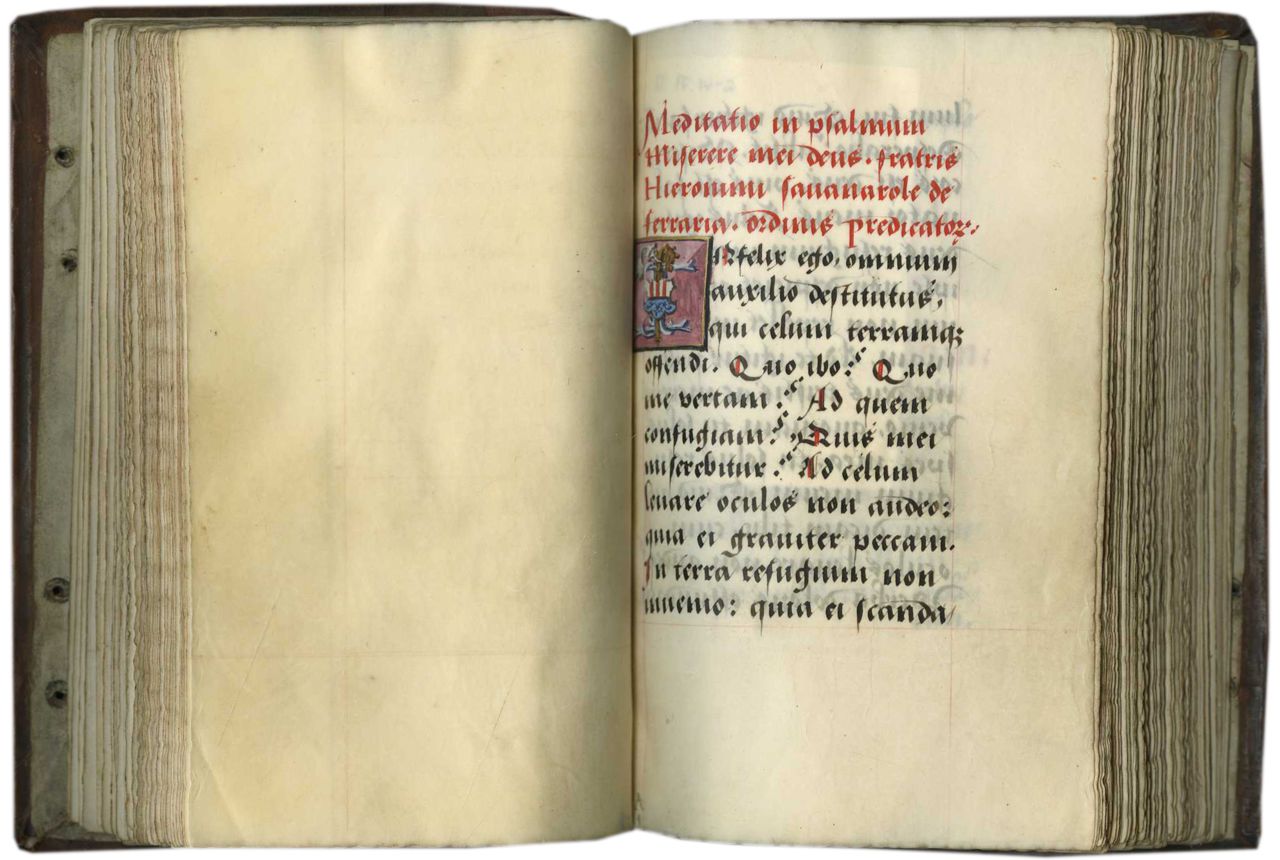

The opening lines of Psalm 51, Miserere mei deus, stand out starkly in this opening from Girolamo Savonarola’s meditation on the Psalm, TM 824, II, ff. 1v-2, Flanders, c. 1490-1510 and c. 1520-1530

The opening lines of Psalm 51, Miserere mei deus, stand out starkly in this opening from Girolamo Savonarola’s meditation on the Psalm, TM 824, II, ff. 1v-2, Flanders, c. 1490-1510 and c. 1520-1530

Here is a copy of one of Savonarola’s final works, a meditation on the penitential Psalm Miserere mei deus (“Have mercy on me, O God”), which he wrote during his time in prison. Savonarola begins, “I am unhappy and stripped of all help, for I have sinned against heaven and earth. Where shall I go? Where shall I turn? To whom shall I flee? Who will take pity on me?” (John Patrick Donnelly’s translation).

The opening of Savonarola’s meditation, TM 824, II, f. 1

This tormented cri de cœur sets the tone for the intensely personal soul-searching that follows. As he ponders each of the Psalm’s nineteen verses, Savonarola acknowledges his sinfulness and prays for God’s mercy. Savonarola completed this meditation just weeks before his death, and it was swiftly smuggled out of his prison to be published. His words spread like wildfire. Within three years of Savonarola’s death the meditation had been issued in over fifteen editions. It also inspired a number of composers, including Josquin des Prez (c. 1450/1455-1521) and William Byrd (c. 1539/1540-1623).

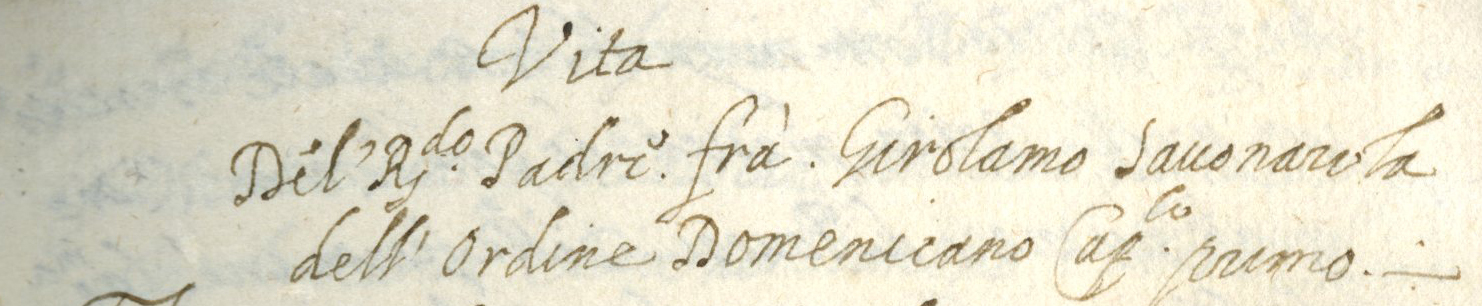

The opening of Savonarola’s vita, TM 708, f. 1, Northern Italy, Tuscany?, c. 1600 (after 1566)

The opening of Savonarola’s vita, TM 708, f. 1, Northern Italy, Tuscany?, c. 1600 (after 1566)

Meanwhile, the miracles Savonarola did not deliver in life were accumulating in his name following his death. Here an Italian translation of Savonarola’s vita, a narrative of his life supporting his veneration as a saint, recounts miracles attributed to him over the 150-year period following his death. Vitae of Savonarola like this one circulated widely in manuscripts, but for over a century after his death were never printed on account of political and ecclesiastical opposition. (Some of Savonarola’s own writings were even on the Index of Prohibited Books!) The vitae were also subject to censorship, and reading them was particularly dangerous under the Medici, who had regained power in Florence and would hold it, almost without interruption, until the eighteenth century.

Carefully preserved and disseminated in the face of official opposition, the texts preserved in these two manuscripts bear witness to Savonarola’s continuing influence after his death, to his textual afterlives.

Full descriptions of the manuscripts discussed here, TM 824 and TM 708, can be found on our website www.textmanuscripts.com