I've said this before, but it is worth saying it again -- everyone at Les Enluminures believes that teaching with actual medieval manuscripts is a transformative experience–one we want to share with as many people as possible. Witness our innovative programs, Manuscripts in the Curriculum I and II (aka MITC), which loan a group of manuscripts to participating schools for a semester to use in the classroom. Readers of this blog may remember previous posts (here and here). Everywhere the manuscripts have visited, they have inspired teachers, librarians, and students (read about some of the programming at different schools on our website in the “program in action” pdfs).

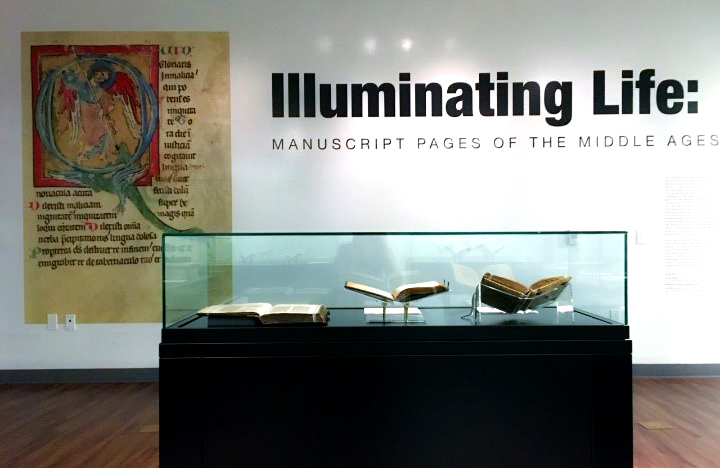

The manuscripts were at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada for the winter term of 2020. And their experience was certainly unique. Both because of the enthusiastic leadership provided by Melissa McAfee (special collections librarian) and Dr. Susannah Ferriera (associate professor, History) and the equally enthusiastic participation of many students, but also (you must have seen this coming), because of the coronavirus epidemic. Their ambitious and beautifully mounted exhibition, “Illuminating Life: Manuscript Pages of the Middle Ages” opened on March 12 and shut down just days later. Undaunted, students at Guelph have produced an even more ambitious catalogue based on this exhibition. And despite the sadly truncated semester, students loved the experience, as you’ll see from today’s post by Alex Wall.

Alex is currently pursuing a MA in History at the University of Guelph. His area of study is the Spanish Inquisition and its role in sixteenth-century Spain's diplomatic relations. He also completed his BA at the University of Guelph, with a double-major in History and English, and is the recipient of the Tri-University Prize for Best Paper by an MA Student (2020), the Department of History Graduate Essay Prize (2020), and the W. S. Reid Essay Prize (2019).

I’m delighted to turn over this blog post to Alex. --Laura Light, Les Enluminures

Historicism: an objective analysis of the past as it actually occurred, untainted by contemporary perceptions. This method of historical study developed by the famed nineteenth-century German historian Leopold von Ranke was revolutionary in its insistence on the use of archives and primary documents. However, a conundrum students of medieval history in North America often face is a lack of access to primary sources. Indeed, during my time as an undergraduate student at the University of Guelph, I would simply have to resort to online translations of medieval works when studying the Middle Ages, which was in many ways unsatisfying. This dilemma is why the “Manuscripts in the Curriculum” program presented by Les Enluminures was such an important experience: it enabled students such as myself to finally study the Middle Ages “wie es eigentlich gewesen.”

Left to right: Thomas Aquinas, Quodlibet, University of Guelph, Archival & Special Collections, s0109b12, Juvenal, Satyrae, Les Enluminures, TM 942, and a Psalter, Les Enluminures.

As part of this program, Les Enluminures loaned eight different medieval manuscripts to the University of Guelph during the Winter Semester of 2020, which allowed several classes of graduate and undergraduate students alike to work directly with them. This was a unique opportunity for us: we would not be learning about the role of religious texts in the Middle Ages or examining pictures of the beautiful art contained within such texts, as I had done in all of my medieval courses up to that point. No, “Manuscripts in the Curriculum'' gave us the chance to explore and, above all, to interact with these texts directly in a way that enabled us to make our own discoveries about these elusive and enchanting primary sources. I was at last presented with the ability to study medieval history through actual primary sources—through windows into the past.

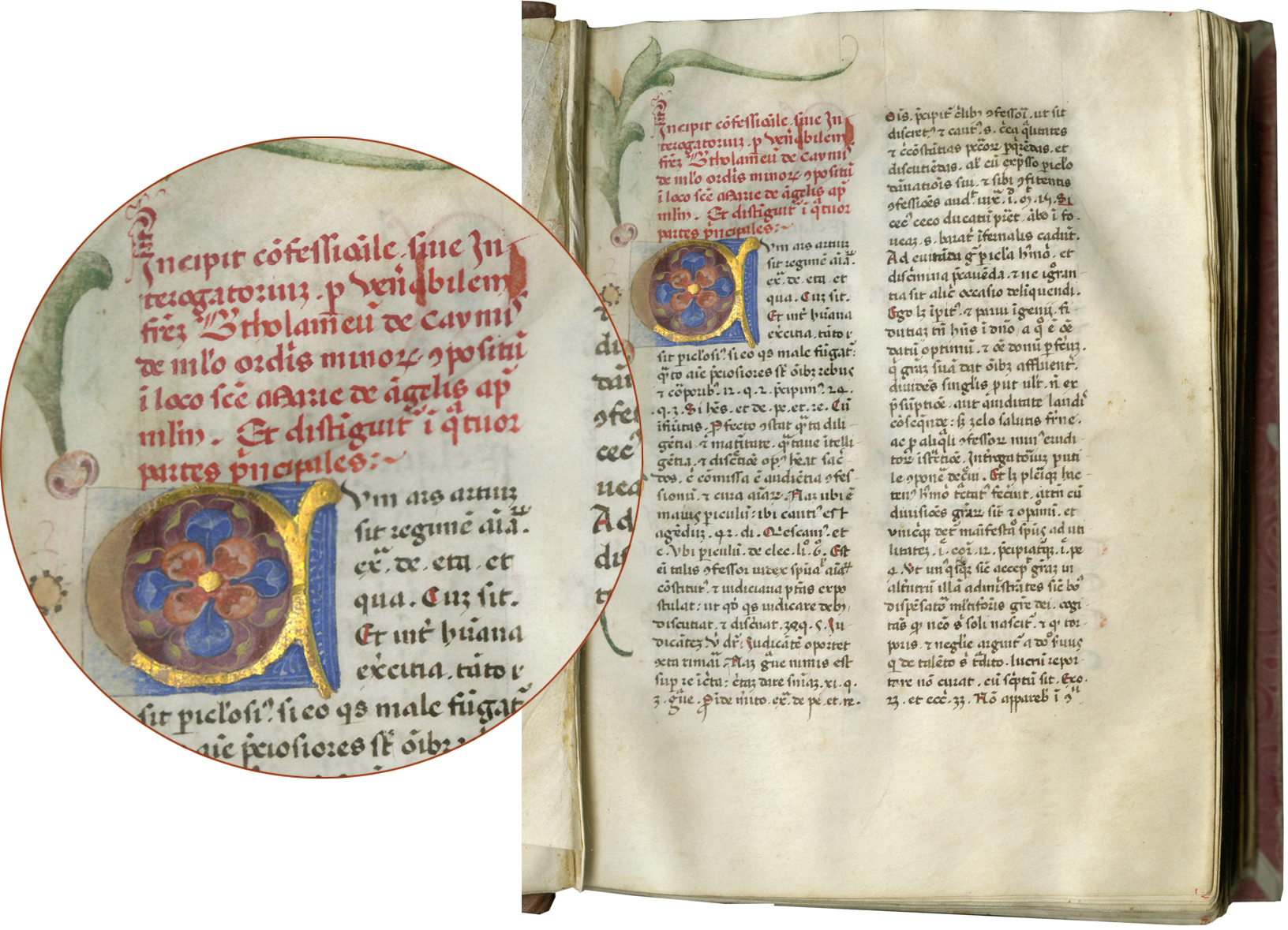

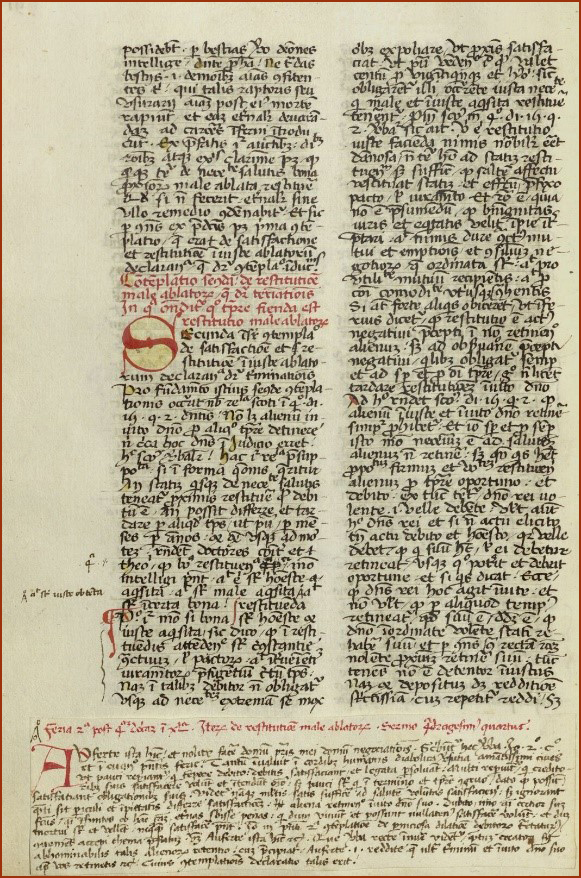

Les Enluminures, TM 976, Confessionale Bartholomei, f. 10.

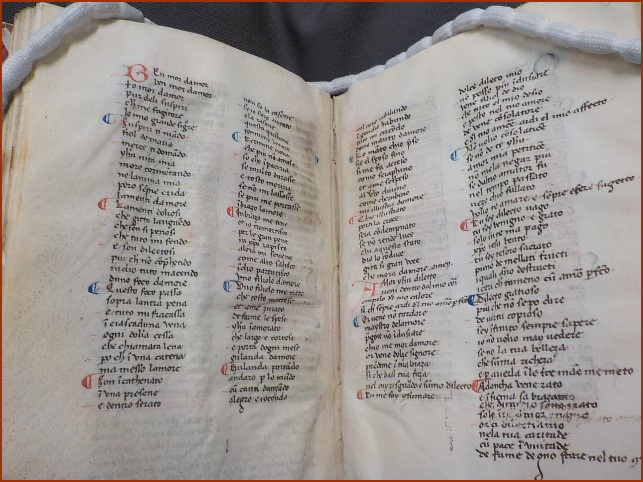

Studying in the university library during dark winter evenings with leather-bound, six-hundred-year-old manuscripts—instead of dusty history books from the library shelves—was quite the exhilarating experience. The manuscripts I chose to work with were the Quadragesimale de Aeternis Fructibus Spiritus Sancti, a book of sermons by the Observant Franciscan Antonio da Vercelli (d. 1483), and the Confessionale Bartholomei by Bartholomaeus de Chaimis (d. 1496, this particular manuscript was copied in 1468, perhaps from the author’s exemplar, or under his supervision). I made several unique discoveries when looking into this window to the Middle Ages. When poring over the pages of the confessional, I was struck by the section occupied by several fifteenth-century Italian devotional poems, such as Spirito Santo, Amore by Leonardo Giustinian (1388-1446). I have a decent ability to read Italian and was delighted to have found medieval text that I could read relatively unhampered and without the use of a dictionary. I had done preliminary research on the Confessionale the semester before, but it is one thing reading a historian’s study on fifteenth-century Italian devotional poetry, and another thing entirely to read the handwritten lyrics of such poems and appreciate the beauty of their script. It gave me the impression of listening to the voices of the past. Reflecting on their presence in a religious manuscript, I was able to understand clearly that medieval religious texts—even confessional manuals—were not exclusively defined by colourless spirituality, and that those who compiled such texts could even combine theological treatises with the beauty of contemporary religious poetry.

Les Enluminures, TM 976, Confessionale Bartholomei, f. 156. Credit: Alex Wall.

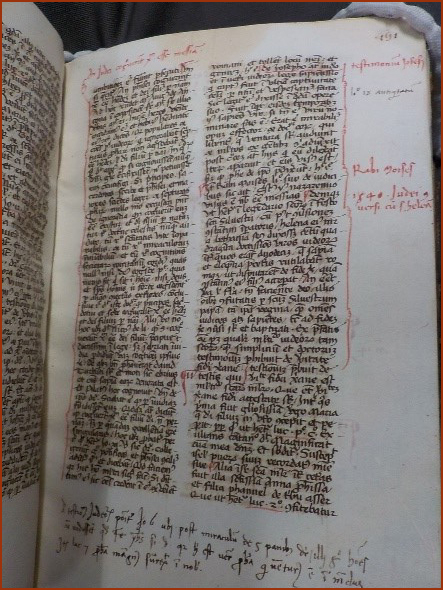

When flipping through the pages of the Quadragesimale book of sermons, I was intrigued to see passages dedicated to Jewish themes, such as the reference to “Rabbi Moses” on folio 151 r.; Antonio da Vercelli included such passages in sermons that were aimed at Jewish audiences with the goal of converting them. I had read about the role of Jews in medieval Italy and how they were often forced to attend sermons aimed at their conversion, but it was quite eye-opening to see references that reflected such a surprising degree of cultural sensitivity. This finding presented me with a different vision of the Middle Ages than the vision of an exclusively Christian society that is typically presented in history textbooks. This notion demonstrates how working firsthand with medieval manuscripts enables one to access a window into the past that is clear, undistorted, and capable of revealing new and insightful findings for the observer.

Formerly Les Enluminures, TM 683, Quadragesimale de Aeternis Fructibus Spiritus Sancti, f. 151. Credit: Alex Wall.

One could argue that these sorts of discoveries can be made by looking at digital copies of medieval manuscripts. While this is true to an extent, there are certain critical points where a digital version quite simply does not compare to the genuine, original manuscript. Obviously, one would still have access to the text of the manuscript, but interacting with the manuscript as a physical object, as opposed to a bunch of ones and zeroes, facilitates a more intimate connection to the past. Carefully flipping through the fragile pages of the manuscripts I chose, observing the striking colours of the ink that in some cases seemed undiminished by time; these things would be lost or lessened by looking at digital scans.

Formerly Les Enluminures, TM 683, Quadragesimale de Aeternis Fructibus Spiritus Sancti, f. 91. Credit: University of Guelph Archives & Special Collections.

Moreover, the medievalist can uncover unique revelations from such a physical interaction: for example, it was by actually beholding the confessional for the first time and holding it in my hand that I truly came to appreciate one of its most defining characteristics: its portability. Before encountering this text I had learned that this manuscript would have been carried from town to town by mendicant Franciscan friars as they facilitated the sacrament of confession for medieval laymen, but I could only get a true sense of this important function of the text by seeing just how small it was for myself. By holding the tiny book in my hands, I understood that indeed this was something that could be carried effortlessly great distances by a barefoot Franciscan in the fulfillment of his religious obligation, and this made me appreciate this important aspect of its utility all the more.

Cover page for the "Illuminating Life: Manuscript Pages of the Middle Ages" catalogue. Credit: Brittney Payer

These discoveries, and many others made by my fellow students, are what studying the Middle Ages should be about: not just learning about what scholars have said about the Middle Ages but interacting with a physical manifestation of that history. The “Manuscripts in the Curriculum'' program gave me and many other graduate and undergraduate students at the University of Guelph the unique opportunity to not just look into a window of history but also to reach through it and discover facets of the Middle Ages that would otherwise have been inaccessible to us. We consolidated and reflected upon these findings in the essays included in the recently-published catalogue “Illuminating Life: Manuscript Pages of the Middle Ages.” These papers discuss a wide array of topics that range from the visual and textual representations of femininity in Germain Hardouyn’s Book of Hours to the material qualities of thirteenth-century “pocket Bibles” to the uses of Juvenal’s Satyrae in late medieval Italian classrooms. Our work is a testament to the fruits of analysing the medieval past directly from primary sources. No doubt von Ranke would be proud of such endeavours.