At first glance, this unlikely juxtaposition seems to mean nothing. Even Mr. Google yields no results in a search that combines this artist, subject, and scholar. But, indeed, one of Damien Hirst’s most inventive new works is the creation of a manuscript album of Renaissance drawings for which the eminent specialist Christopher de Hamel supplied the background history. Intrigued? Read on …

Damien Hirst’s latest show “Treasures of the Wreck of the Unbelievable” has been on exhibit in Venice at the Palazzo Grassi and the Punta della Dogana since April 9, 2017. It will end on December 3, 2017. Technically the exhibition is not part of the Venice Biennale but its opening and closing dates coincide closely with this grand event.

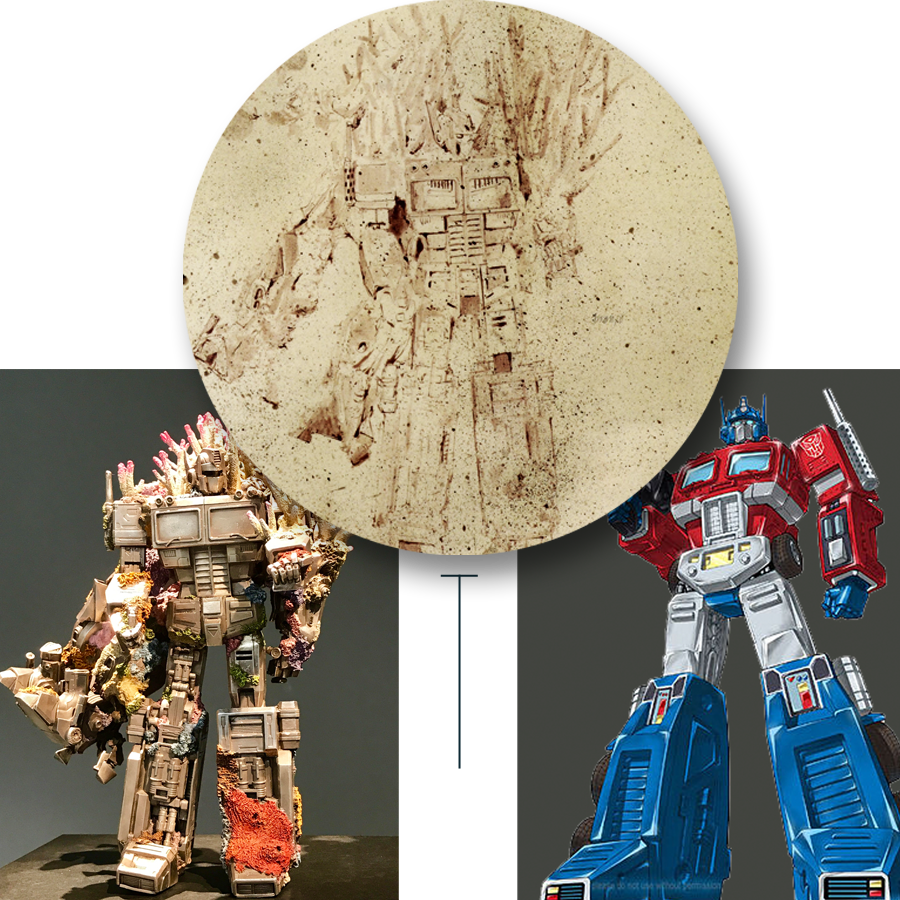

The pretense of Hirst’s show of 100 objects large and small is the supposed recovery in 2008 of an underwater treasure from the wreck of the vessel known as the Apistos (which is Greek for the “Unbelievable”). From the seabed emerged a unique cargo of ancient artefacts, barnacle-encrusted and wrapped in corals, of the collection of a freed Greek slave named Amotan from the mid-first to the early-second centuries CE. A continuously looping video even shows professionally-outfitted divers salvaging the sunken objects one by one.

There is little agreement about the critical success of this show. “Disastrous,” “a fantasy too far,” “a titanic return,” “an unbelievable journey,” “comic and monstrous, “bling” – these are just a few of the words used so far to describe Hirst’s exhibition.

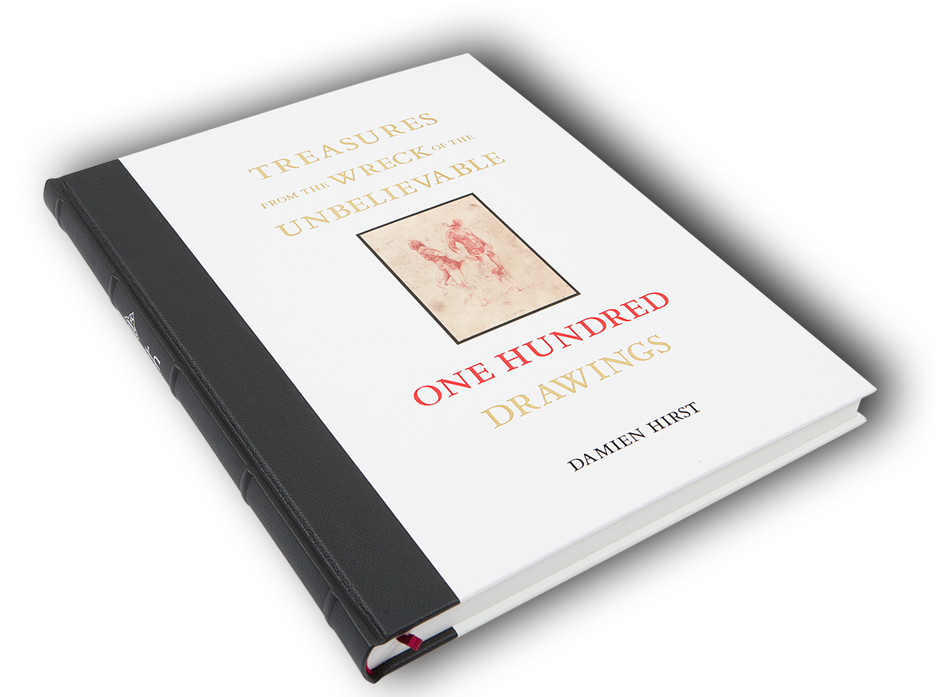

Little is made of the 100 drawings that adorn the walls of one large room in the Palazzo Grassi. They are summarily mentioned in just one review. They are identified only with titles in the convenient hand-out given out to museum-goers. They are reproduced in a book “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable: One Hundred Drawings.” But, the one-page introduction to the book offers little clarification on what the drawings are doing in the show. Nor does the book adequately explain many of the unusual features of the drawings. Perhaps that’s the point.

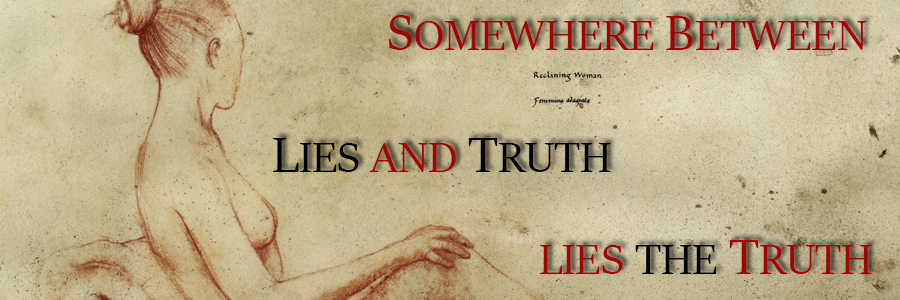

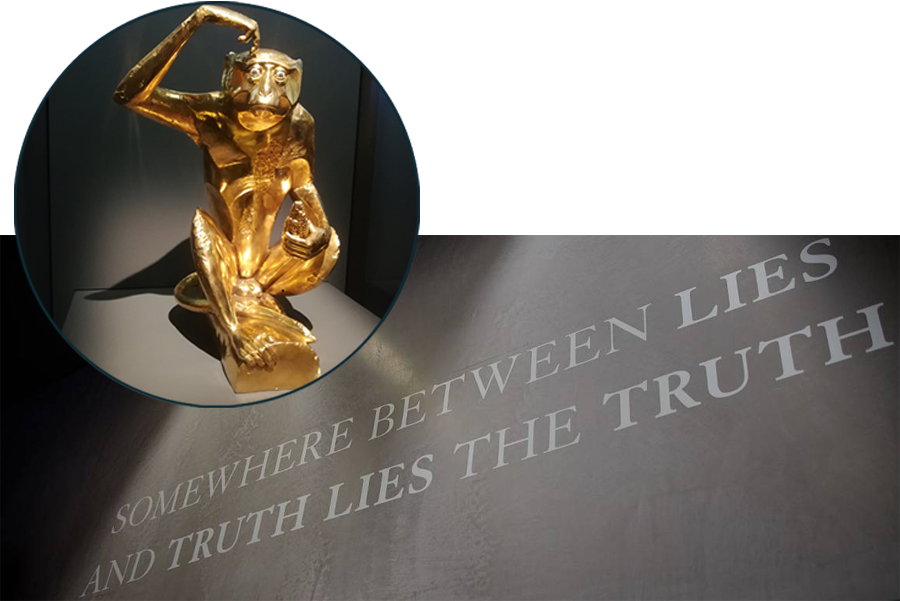

At the entrance of the Punta della Dogana the wall text reads “Somewhere between lies and truth lies the truth.” This is also what the second title page of the book reads. Is Hirst saying: “You figure it out,” or, “don’t bother”? Well, I’m intrigued, so I’d like to take a stab at understanding better the drawings.

Here’s what we learn about the drawings from the book. The drawings are presented as depictions of the 100 objects in the exhibition. However, since they are said to be “Florentine workshop drawings” from the Renaissance, it is immediately obvious they cannot be drawings after life of the objects from antiquity, which were buried in the sea at the time the drawings were (purportedly) executed. So, instead, the drawings form part of the tradition of depicting antiquities based on their classical descriptions; the “description from which the drawings presumably originate has not been found and their provenance is likewise difficult to ascertain,” the introduction goes on to say.

Quoting a spurious forthcoming article by Christopher de Hamel, the introduction speculates that the collection may have been the property of Cardinal Flavio Chigi (1631-1693), librarian of the Holy See, and further traces the provenance backwards and forwards in Rome and then finally to “English aristocrats on the Grand Tours of Europe” in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, a circumstance meant to lend credence to the many collectors’ stamps and marks, as well as the scrawled annotations, on the drawings.

Jacob Ferdinand Voet, Portrait of Cardinal Flavio Chigi (detail), Ariccia, Palazzo Chigi

Although the introduction does not directly say so, the English provenance of the drawings presumably also accounts for the dismemberment of the album, like many manuscripts taken apart in Italy and the leaves sold separately largely through the English art market. Damien Hirst thus stands at the end of this illustrious, though fictitious, line of owners. Damien Hirst as Artist/ Art Historian/ Art Collector?

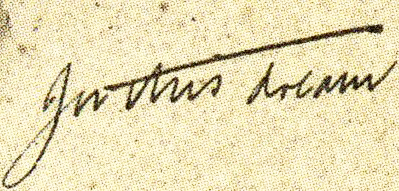

Now what else can we learn about the drawings? Hirst insinuates his art-historical mastery at every opportunity, with references to Caravaggio, William Blake, Durer, not to mention Egyptian bronzes and Greek statuary. All the drawings bear the inscription “In this dream,” which is an anagram for the artist’s name Damien Hirst. They are thus all signed.

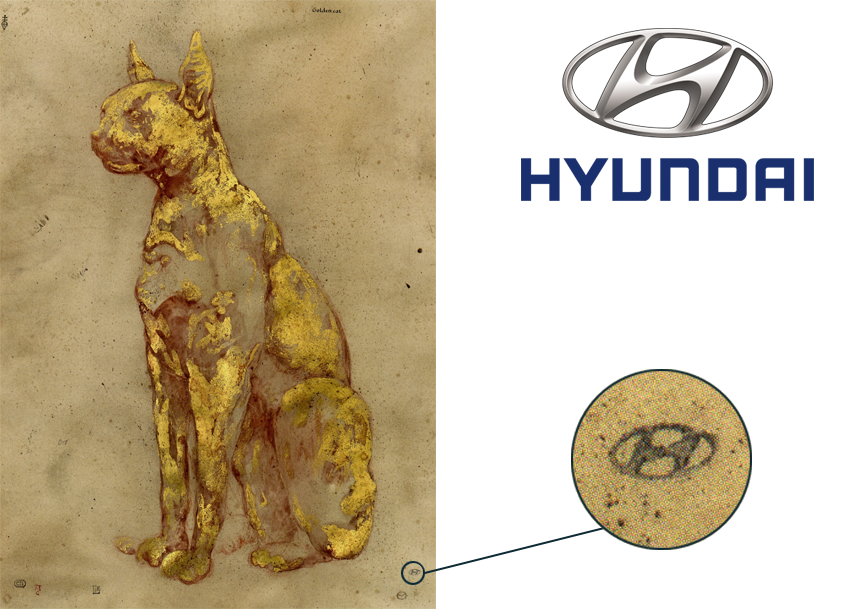

The collectors’ marks, although they resemble those stenciled stamps used by collectors to signify ownership, are in fact monograms from today’s commercial world – cars predominate, Opel, Hyundai, Audi, Mitsubishi.

There is also a stenciled image of Optimus Prime, a transformer from a cartoon of the 1980s and recently seen in Michael Bay movies.

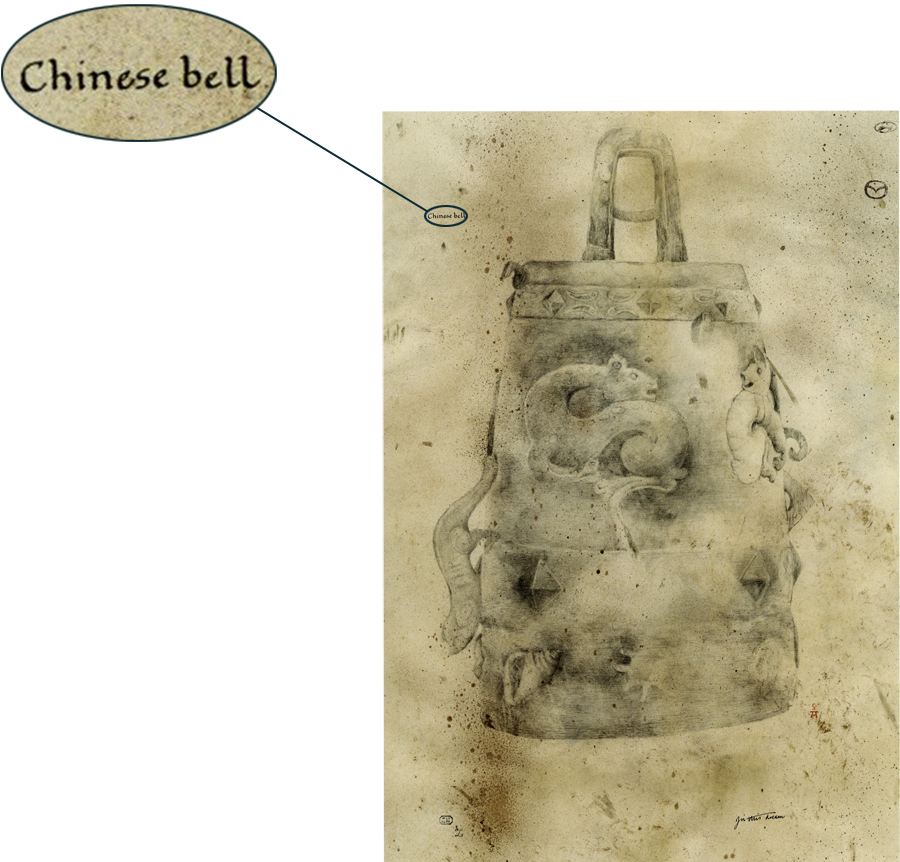

In addition to the signature-inscription, the drawings all have titles in clever imitation of humanist script. Some (but not all) of these titles (Chinese bell, Pegasus, Golden monkey, Two daggers and golden crowns in petrified honey) correspond with a reproduced list in an inventory presumably by an English aristocrat-collector that accompanies the drawings and was allegedly part of the album. Patricia Lovett, a well-known and remarkably skilled contemporary British calligrapher, penned the titles and the inventory.

The title of the inventory is itself playful: “A History of the World in a Hundred Objects.”

This is the name of a BBC television show written and presented by Neil MacGregor former head of the British Museum and now considered something of a television classic like Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation series.

As Neil MacGregor puts it “I'm travelling back in time, and across the globe, to see how we humans over 2 million years have shaped our world and been shaped by it … from a Stone Age tool to a credit card.” Damien Hirst as Neil MacGregor?

What of the drawings themselves? In pen and ink, graphite, or charcoal on parchment (or occasionally paper) the drawings are beautifully rendered, finely modulated studies of the objects, often skillfully enhanced with gold or silver leaf and pastel. As is expected with animal skin, the parchment often shows flaws, missing corners, and obvious follicles—just as original manuscripts do. This quality only enriches the effect of the finished object. “Florentine workshop drawings” these are not. So what are they like? They don’t much resemble drawings Hirst has made as preliminary studies for his own art works. They bear some similarity to his drawings copying old masters (I’m thinking of a drawing after Delacroix) in the time-honored tradition practiced by artists from Rubens to Picasso and in art schools all over the world today.

Detail of "Study after Delacroix (the Orphan Girl in the Cemetery)", 1981. 340 x 280 mm | 13.4 x 11 in Pencil on paper. Photographed by Gareth Winters © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd.

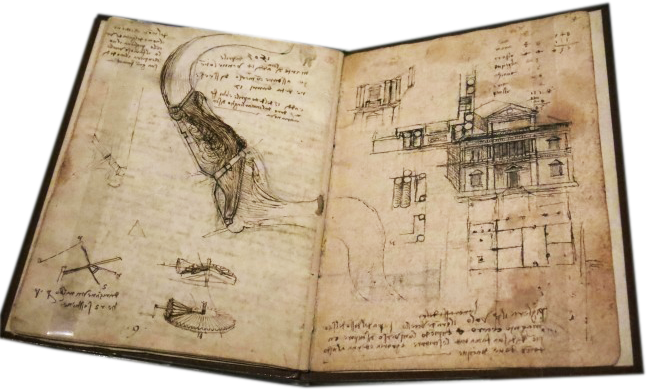

After all, these are also drawings meant to be copies after earlier works. But, aren’t they meant to recall something else? They show a remarkable range, surprising precision, deliberate playfulness, consummate skill. They evoke intrigue and curiosity. Like much of Hirst’s work, they are knowingly provocative. Is it too farfetched to think of one of the most famous Renaissance manuscript albums of all time?

Like the Leicester Codex by Da Vinci? Damien Hirst as Leonardo?

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”