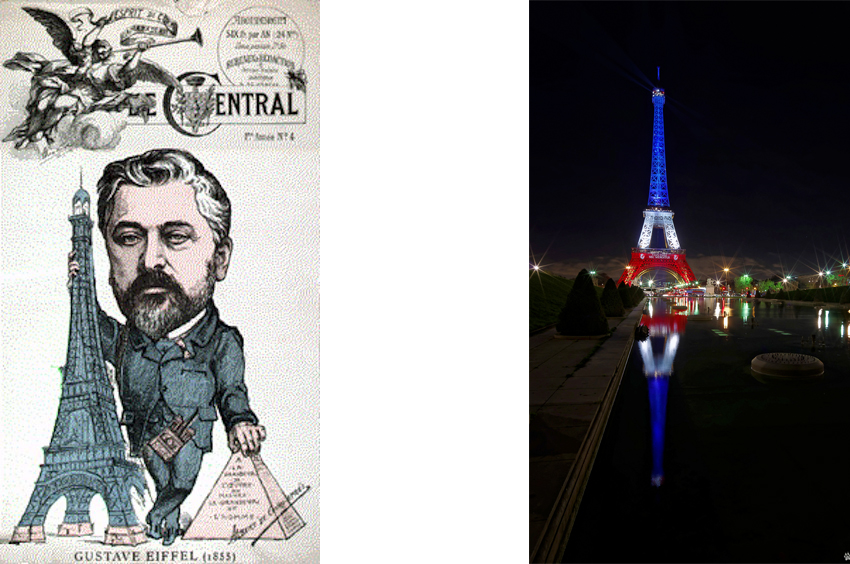

Praised as “the magician of iron,” Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923) was also scorned for his “useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower,” which some described as “ridiculous … dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack.” This previously unpublished manuscript portrays another side of Gustave Eiffel. It is a Prayer Book he commissioned as a family heirloom for his daughter Claire (1863-1934) between 1898 and 1899.

Caricature of Gustave Eiffel, who compares his tower to the Egyptian Pyramids; The Eiffel Tower, 2015

Napoleone Verga, Prayer Book commissioned by Gustave Eiffel, Renaissance style frontispiece; p. 41 ter, Virgin and Child with Infant St. John the Baptist, St. Francis, and unidentified saint

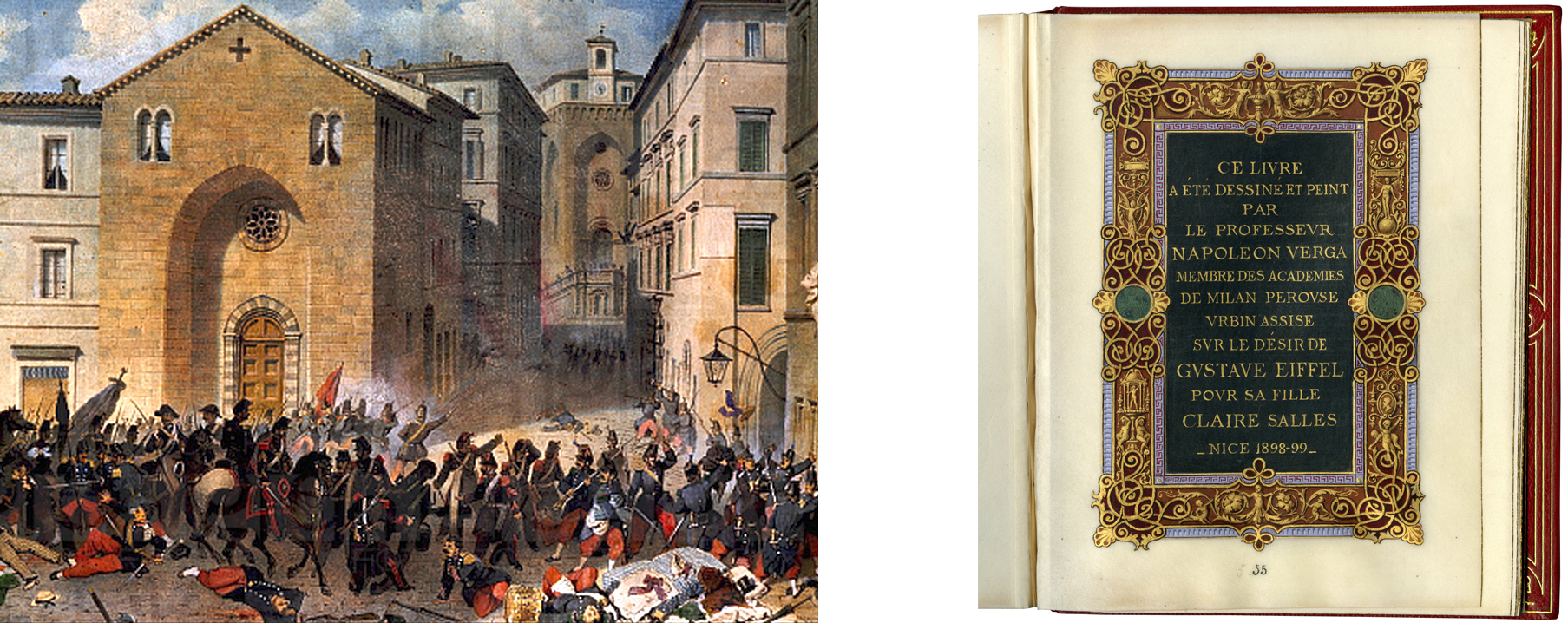

Whereas the Eiffel Tower was avant-garde, employing a new lattice style of construction made up of cast iron and wrought iron framing, Eiffel turned to the past for his Prayer Book. He ordered it from Napoleone Verga (d. 1916), who painted page after page of miniature versions of High Renaissance paintings (66 total), opulently rendered in tempera and gold leaf on parchment in the manner of medieval manuscript illumination. Little is known today about Verga, a painter of the Romantic School, who was a professor of design in Perugia, but in the nineteenth century he was highly acclaimed as “superior to almost all other ancient magnates in the art of illuminations on vellum.” Perhaps the Verga and Eiffel met in Nice, where Verga emigrated from Perugia, while Eiffel was working in 1886 on his project for the dome of the Observatory of Nice.

Napoleone Verga, The Massacre at Perugia, 1870, Perugia, Fondazione Accademia P. Vannucci; Prayer Book, p. 55, colophon

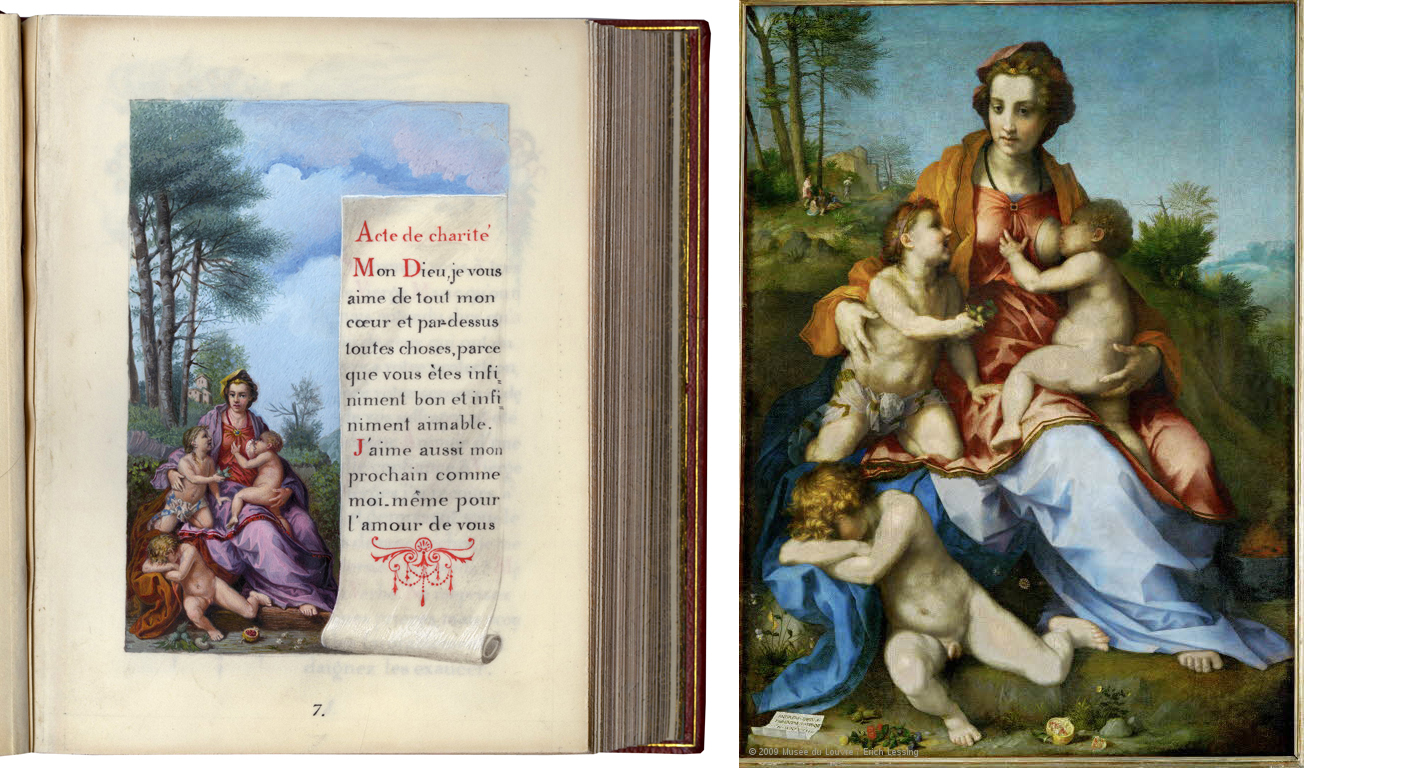

Among the important Renaissance artists who inspired Verga are Raphael, Botticelli, Correggio, and Andrea del Sarto. Verga used well-known paintings by these masters to illustrate appropriate sections of the Prayer Book.

Prayer Book, p. 22 ; Raphael, La belle jardinière, or Virgin and Child with Saint John the Baptist, 1507, Paris, Musée du Louvre

Prayer Book, p. 35 ; Botticelli, Madonna of the Pomegranate, c. 1487, Florence, Uffizi

For example, Raphael’s painting of the Madonna and Child with John the Baptist introduces a prayer for “my husband and my children” (p. 22) while Correggio’s Noli me tangere precedes a prayer to Jesus (p. 13). Andrea del Sarto’s Madonna of the Harpies set within a frame and richly finished with text and gold illustrates the Ave Maria (Hail Mary) (p. 2), and Botticelli’s Virgin with the Pomegranate comes before miscellaneous prayers (p. 35).

Prayer Book, p. 13 ; Correggio, Noli me tangere, c. 1523-24, Madrid, Prado Museum

Prayer Book, p. 7 ; Andrea del Sarto, Charity, 1518, Paris, Musée du Louvre

In vivid blues, reds, and greens with some gold and silver leaf, these paintings are not exact copies of High Renaissance paintings; rather they are free renditions closely inspired by the originals. Curiously, the original manuscript even includes a list that identifies the sources of the paintings page by page (Are these credits by Verga? Or references for the reader?).

Prayer Book, p. 52, Table

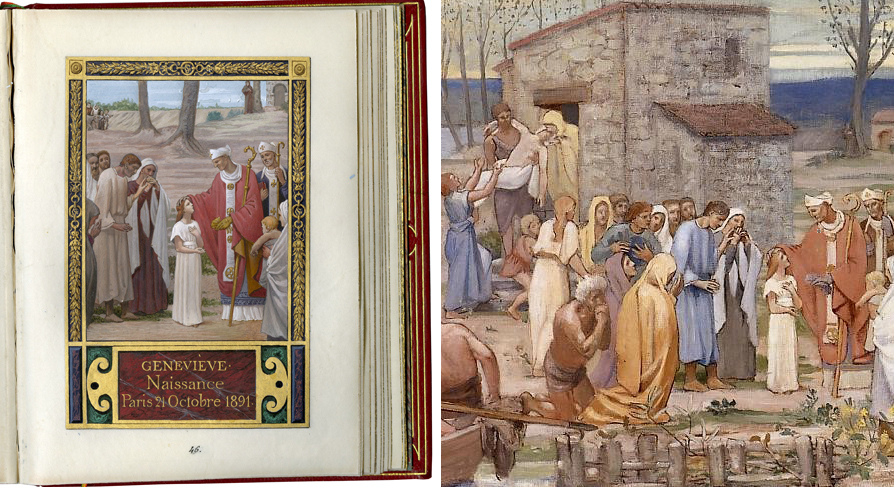

For the section on the genealogy of Claire’s family toward the end of the manuscript, Verga departed from this practice of using High Renaissance models. On p. 46, for Claire’s daughter, named Genevieve, he borrowed the central scene of the fresco of the Childhood of Saint Genevieve that Puvis de Chavannes had just completed in 1874-78 for the Church of Ste.-Genevieve in Paris (today known as the Pantheon). Compare the triptych of the same subject in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

Prayer Book, p. 46; Puvis de Chavannes, La vie pastorale de sainte Geneviève, 1879, Pasadena, Norton Simon Museum (detail)

Surely hubris dictated the next illustration on page 48 devoted to Claire’s famous father, Eiffel himself. Tributes to his greatest achievements are arranged in a frame, starting with the Pia Maria Bridge in Portugal, followed by a portrait medallion of Eiffel, then images of the Eiffel Tower, the Observatory in Nice, and the Viaduct of Rouzat in central France.

Eiffel & Cie, Maria Pia Bridge, 1877, Portugal, Porto; Rouzat Viaduct, 1869, France, Rouzat; Charles Garnier and Gustave Eiffel, Nice Observatory, 1878, France, Nice

A lavish Art Nouveau binding in red morocco with gold inlay by Petrus Ruban, who won a silver medal for his accomplishments in 1886, the same year that Eiffel won his bid for the tower, completes the Eiffel Prayer Book, as a veritable tour de force.

Prayer Book, p. 48, Eiffel Family, images of Gustave’s Paris tower, Rouzat and Pia Maria bridges, and the observatory in Nice; binding

Gustave Eiffel’s Renaissance-inspired Prayer Book adds another dimension to our understanding of the man and the engineer, whose legacy today lies not only in the construction of one of the world’s most iconic monuments but also in the origins of the modern skyscraper. Defending his tower, Eiffel wrote “can one think that because we are engineers, beauty does not preoccupy us…?” The newly discovered Eiffel Prayer Book survives as another testimony to what Eiffel may have meant by “beauty.”

For the Eiffel Prayer Book and fourteen manuscripts and books inspired by the medieval and Renaissance eras, see our latest Primer, Neo-Gothic Book Production and Medievalism.