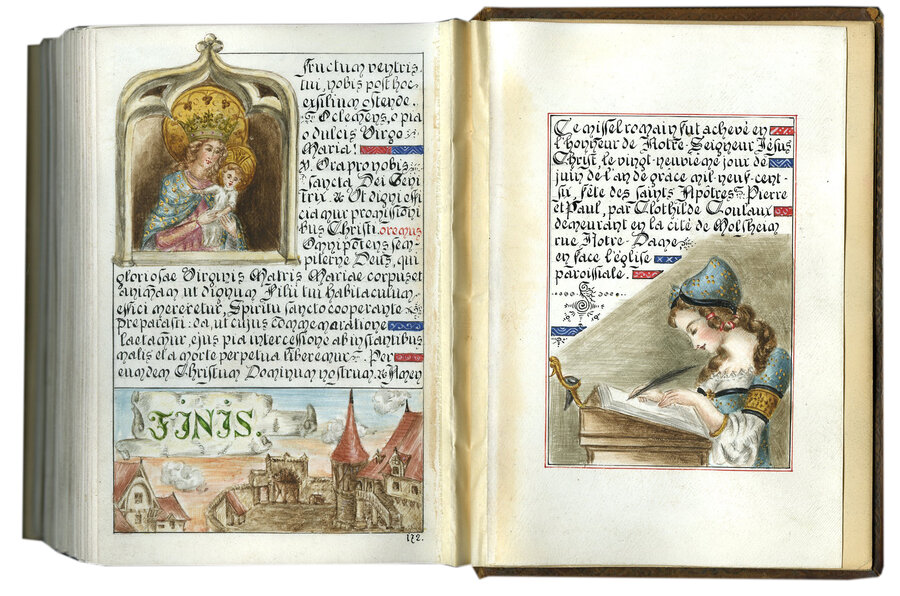

Forgotten today, Clothilde Coulaux, was responsible for the writing and illuminating an enchanting Missal dated June 29, 1906. She signed her manuscript, full of literally hundreds of illuminations, on the last folio, “living in the city of Molsheim on the street of Notre-Dame facing the parish church.” There she included a delightful self-portrait of herself looking like a fairy-tale princess seated at her lectern writing.

Missal, by Clothilde Coulaux, p. 172-173, Colophon, illustrated by a miniature of a young woman writing (a self-portrait?)

A decade earlier in 1896 Clothilde took second prize in a competition for illuminators, for which she received an annual subscription to the magazine Coloriste-Enluminure, a journal promoting manuscript illumination as a domestic activity most suitable to young women. The other competitors were all women.

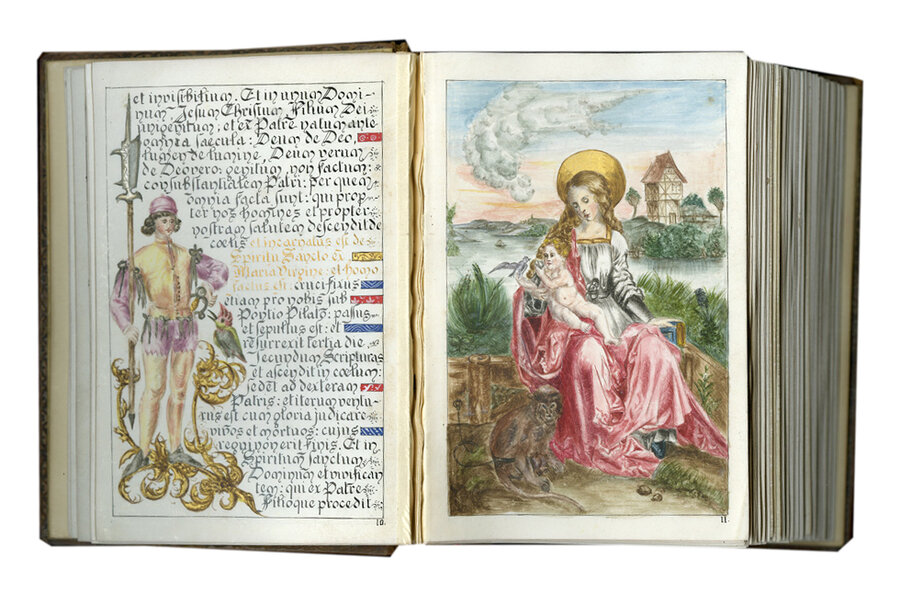

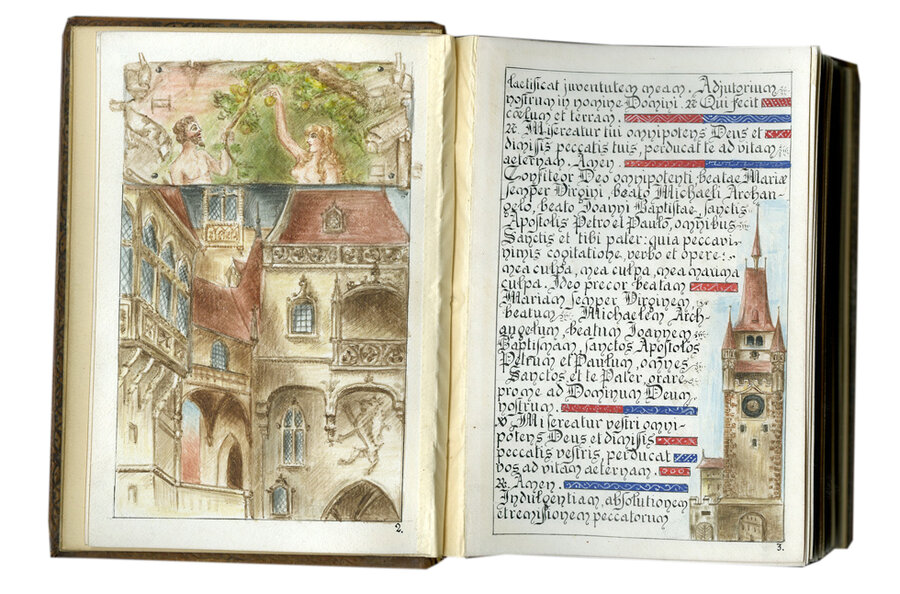

Clothilde’s Missal reveals her considerable accomplishments, her wide range of artistic sources, and her lively imagination. Many images are faithful reproductions of German Renaissance prints mostly by Albrecht Dürer, but also Hans Holbein and Urs Graf; still others are likely based on personal observation (local street scenes, church spires, images of daily life).

Coulaux Missal, p. 10-11, Virgin and child, after Albrecht Dürer’s engraving, Virgin and Child with a monkey

A Crucifixion resembles a stone sculpture in her home-town church, and the opening pages may depict the tower and porch of the same church, especially considering she took pains to write that she lived facing the parish church.

Coulaux Missal, p. 2-3, Full-page, Adam and Eve at the top; below, a street scene, possibly depicting a scene in Molsheim or elsewhere in Alsace

In this make-believe world of the Middle Ages there is an owl in a belfry, a cat in a window, a man dragging a pig, a lady serving wine, a jester with a basket of fruit, and countless lords and ladies, all in fanciful medieval dress, private daydreams of a time long ago.

Coulaux Missal, p. 75, owl in belfry; p. 9, cat in window; p. 135, man and pig (details)

“It seems that people like the Middle Ages,” so wrote Umberto Eco in 1986 in a book of essays called “Dreaming the Middle Ages.” Those who chronicle medievalism – defined as the "continuing process of creating the Middle Ages” – point to a sort of nostalgia about medieval times that indicates dissatisfaction with contemporary life. Certainly Clothilde, gazing at medieval buildings outside her window a century ago, dreamed of the medieval era. A host of scholars today argue that phenomena as diverse as Hollywood movies like Braveheart, video games like Elder Scrolls, television shows like Game of Thrones, and even the Trump Tower as a model of feudalism's split between the well-to-do and the masses reflect modern-day society’s dreams of the Middle Ages.

Read our just-published catalogue “Neo-Gothic Book Production and Medievalism” for further examples of manuscripts that prompt an exploration of the meaning medieval had, then and now.