“Why do you sell jewelry?” “What does jewelry have to do with medieval manuscripts?” People often ask me these questions, especially at art fairs, puzzled I guess by how different the media are. In some ways, the answer is simple, and it’s the one I usually give. Like medieval manuscripts, jewelry, whether pendants or rings, are small precious things. They are similarly characterized not only by their composition from luxurious materials (gold, gemstones, like lapis lazuli) but also by the intimate experience engaged in between viewer and object while handling a book or a jewel.

There are other parallels also. Books communicate the written word, and so do many rings. Sometimes the words on a ring declare ownership, such as in this Byzantine ring, whose Greek inscription gives the name of the owner – Marianou.

Les Enluminures, Byzantine Ring with Cruciform Monogram, Early Byzantine, mid-6th -7th century (R944)

Or words might express a sentiment. Here is a one-word ring; the word is “love.” Sentiments of love are literally spelled out more explicitly on this Falize bracelet enameled Aultre n’auray (“I would have no one but you”).

On the left: Lucien Falize, Enameled Hinged Bracelet, France (Paris), c. 1881. On the right: Robert Indiana, "Love" Ring, United States, 1969 (R704)

Posy rings, of which we have a very wide selection, are the category of word-rings most closely related to books or literature. Taking their name from the word “poésie,” they bear rhymed inscriptions on the interiors of their bands such as: “Hearts united live contented,” “A loving wife during life,” or “In thy sight is my delight.” Shakespeare mentions them in his plays. But that’s a subject for another blog.

Les Enluminures, Posy Ring “Hearts United Live Contented” (R930); Posy Ring, "A loving wife during life" (R716); Posy Ring, "In thy sight is my delight" (R300-3)

In today’s blog, with special thanks to Philippe Cordez, I want to consider another relationship between books and jewelry, one that he has called “bibliomorphy.” Bibliomorphy is the study of objects that are recognizable as books (“biblio,” meaning book) because they use the form of the book, but that are created in combination with the forms and functions of other object types (“morph,” meaning to transform).

Philippe Cordez and Julia Saviello, Fifty Objects in Book Form: From Reliquary to Laptop Bag (2020; only available in German). See also Philipppe Cordez on “Feigned Books”

We have several book-shaped objects among our jewelry. Take for example this pendant in book form. It looks like a book. It has a spine with three raised bands. It has front and rear covers. It has a fore-edge and top- and bottom-edges resembling pages. It has a clasp to hold the covers shut. The object is composed of gilded silver, as are some bindings, with a glass plaque depicting the Nativity in verre églomisé (reverse glass painting) inset in the front cover and in the rear cover the Annunciation. It even opens like a book with a hinged lid. But it isn’t a book. Opened, there are no pages or any words. Instead, it exposes another painted glass plaque of Christ as Ecce Homo, opposite which is a place for a relic (now missing) surrounded by a golden aureole against a red background. Perhaps the relic was a fragment of the True Cross visually compared with the body of Christ facing it. Our pendant is a book-reliquary that encourages an intimate devotional experience between the viewer and the object. It is a perfect example of bibliomorphism.

Les Enluminures, Reliquary Pendant in Book form, Southern Germany, probably Augsburg, c. 1550

Here are two other examples of book-reliquaries. Known examples date from the sixteenth and seventeenth century, and a center in southern Germany, such as Nuremberg or Augsburg, was probably responsible for their production.

Les Enluminures, Reliquary Pendant in form of a Book, probably southern Germany, 1630-40; Reliquary Pendant in form of a Book, probably southern Germany, late 16th-early 17th century.

One of my favorite book-jewels is a pomander in the shape of a book. This one dates from the first half of the seventeenth century and was probably crafted in Southern Germany, finely engraved on gilt silver.

Les Enluminures, Pomander in the form of a Book, Southern Germany, c. 1620–1650

The word pomander derives from “apple of amber” (Latin: pomum ambrae), and a typical pomander was shaped like an apple and contained smelling scents, such as musk, aloe wood, or ambergris. Worn directly on the body or suspended from a belt on a chain, pomanders contained fragrances whose smells were beneficial for diverse purposes. This one is very unusual. Like the book-reliquaries, it boasts a hinged binding, and it displays simulated pages along its edges. A small spoon serves as the clasp.

Les Enluminures, Pomander in the form of a Book, Southern Germany, c. 1620–1650

Inside there are twelve compartments, meticulously labeled with the names of different spices, scents, and balms. Take the spoon and taste or smell the balm for frizzy hair (I need that!), one for snake bits, one for digestion, for apoplexy, and so forth. Poison plum, amber, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, lavender, rose, these are among the substances included.

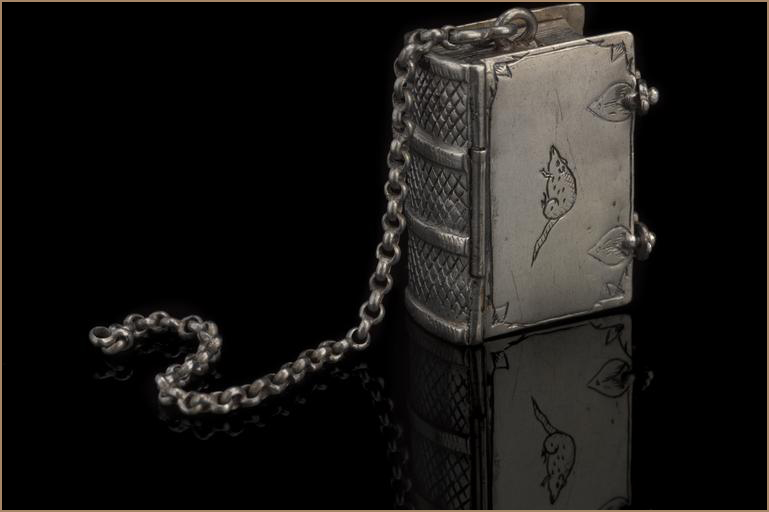

Why is this pomander in the form of a book? Discussing a related object in Cordez’s book, a tiny silver pomander in the Science Museum in London, Dominic Olariu suggests that its book form alludes to the “book of books” and that it thus would have functioned as a sort of amulet, offering not only a natural substance but the power of the Holy Word as an antidote to various ills. In the case of the London pomander, the small rat graphically engraved on the cover refers directly to a specific malady – the plague, which the scents in the book protected against.

Silver pomander, in the form of a book, containing 6 compartments, with a rat engraved on the side, and chain for suspension, c. 1601-1700

©The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, London

The art of object combination is understudied because such combined objects often fall through the cracks of serious research, since they don’t fit easily into categories, being neither one thing or another, not really book or jewel (see Cordez, p. 7). Cordez’s examples of bibliomorphism begin in the fourteenth century and continue to the present day (his last example is the laptop bag). But he puzzles over why the phenomenon did not occur earlier in the Middle Ages, wondering if it was the invention of the printing press and the diversification of book types that inspired bibliomorphism Taking up the challenge posed by Cordez, we will look more closely at some examples of bibliomorphism from the Gothic era, like this one, in the next blog, Part 2, Gothic Bibliomorphy.

Les Enluminures, Diptych Pendant with Virgin and Child and Crucifixion Scene, Probably Germany (Lower Rhine?), late 14th century

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!