Everyone likes a good story. In a way, the history of the written word is an exercise in grabbing the attention of your audience, whoever they might be. Performers do this by “breaking the fourth wall” and talking to us directly (you hate that as much as I do, right?). Pictures also play this game in books and illuminated manuscripts.

Some books have none.

B.J. Novak’s The Book with No Pictures, 2014, a comical children’s book and New York Times best seller, called “a riotously fresh take on breaking the fourth wall.”

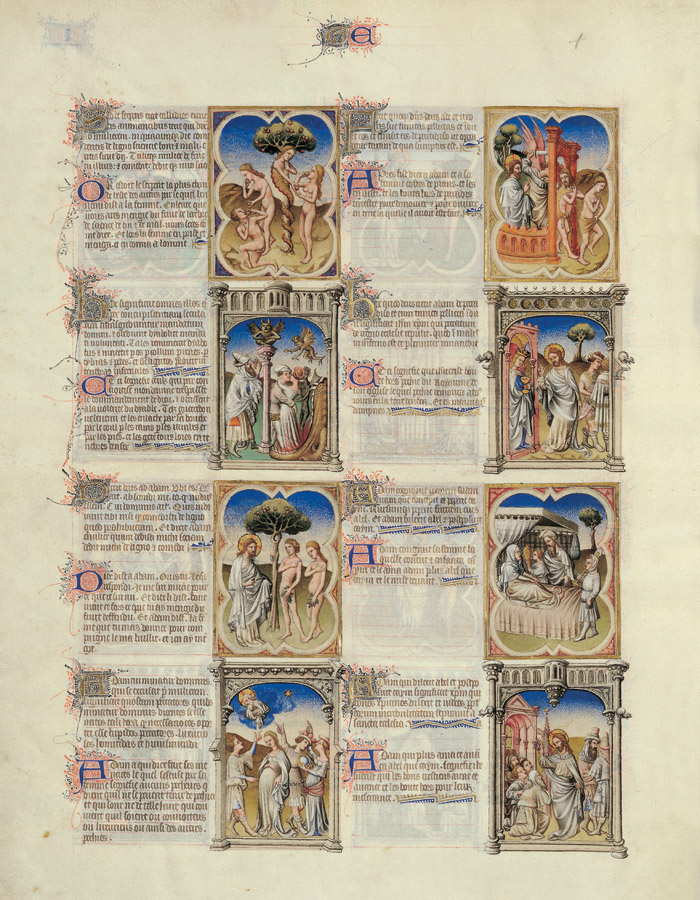

While other books are mostly pictures, like the Bible moralisées (“Moralized Bibles”), comprised of hundreds of pictures with pithy captions explaining each scene from the Bible.

Scenes from Genesis in the "Bible moralisée of Philippe le Hardi", a manuscript with around 5,000 miniatures by at least six painters working between 1402 and 1493 (Paris, BnF, MS fr. 166, f. 3v)

Somewhere between these two is the Bible historiale, a potent mixture of the Bible and history written in French often copied with colorful pictures heading each section. Composed by Guyart des Moulins in the late 13th century, the Bible historiale translates sections of the Bible into French and presents them with extracts from Peter Comestor’s Historia Scholastica, a history text that served as school book for centuries.

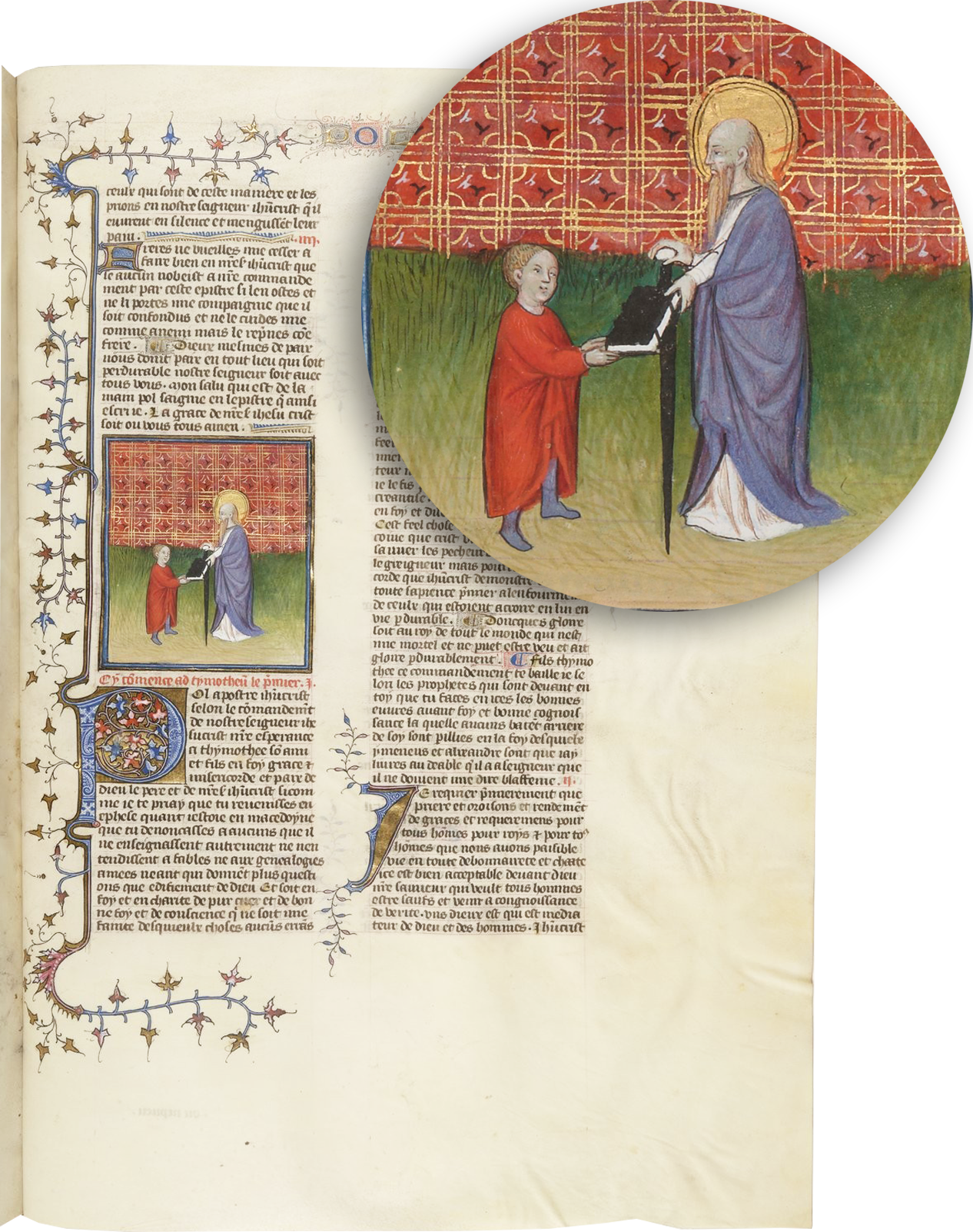

A miniature with Saint Paul opening the Book of Timothy in a Bible historiale, c. 1405 (Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, MS 5058, f. 471)

There was real demand in the 15th century for biblical texts in French––the language spoken at Court, on the street and (presumably) in the bedroom (this was the topic of our exhibition in New York early this year, featured in Laura Light’s blog post, and in our catalogue Shared Language: Vernacular Manuscripts in the Middle Ages ). The popularity of the Bible historiale can be gauged by the number of recorded copies: 143 have been catalogued by Eléonore Fournié.

In October Les Enluminures exhibited three miniatures from a Bible historiale in New York. Each one grabs attention with vibrant and varied pigments set against red backgrounds with delicate gold patterns. They are attributed to the workshop of the Virgil Master, who painted at least five books owned by Jean, Duke of Berry, the most famous French bibliophile of the Middle Ages, and owner of one of the most famous of all medieval illuminated manuscripts, the Très Riches Heures.

Portrait of Jean de Berry, Calendar Page of the Très Riches Heures , Musée Condé, Chantilly, France

Here are our miniatures; the first miniature was once at the beginning of the First Epistle of John, the second, at the beginning of one of the Pauline epistles (perhaps Ephesians), and the third probably opened the second book of Maccabees.

Les Enluminures, Three miniatures from a Bible historiale, Workshop of the Virgil Master, Paris, c. 1400-1405

Each miniature stands in for an entire book of the Bible and brought the stories to life, especially for the contemporary 15th-century reader. One shows a kneeling messenger handing a letter to a group of bearded men, seven of them with red and white roundels on their chests. This is a rare depiction of the badge, or rouelle, mandated to be worn by Jewish people through the reign of Charles VI and the expulsion of 1394––here portrayed as an anachronistic component of Jewish identity. The Bible historiale was a true milestone in the impulse toward explaining the Bible to the “grand public,” and the enigmatic blend of text and image remains understudied.

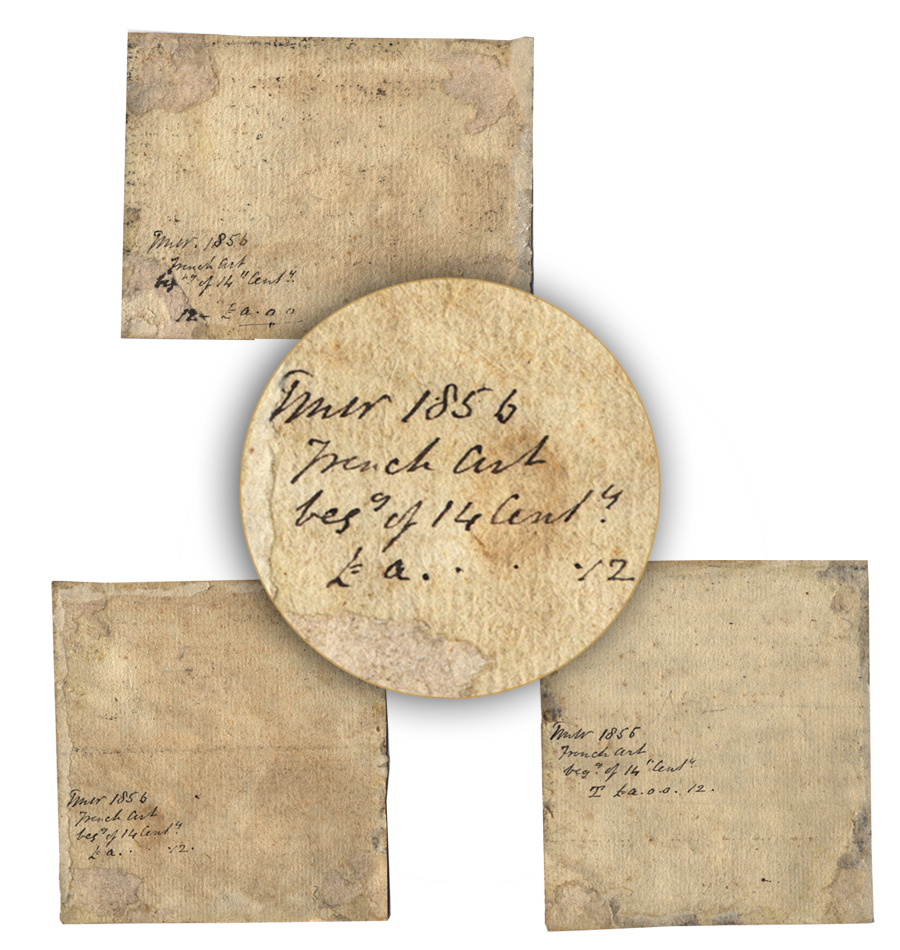

We know a good deal about these three miniatures and their parent manuscript because they belong to a group of thirty-six others. The largest part (twenty-one of them) are among the collections of the Free Library of Philadelphia. When complete the parent manuscript’s mise en page would have mirrored the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal Bible historiale pictured above (MS 5058). It’s unknown how or when the parent manuscript was dismembered but it certainly happened before 1856, when a large group was acquired by Thomas Miller Whitehead, who inscribed his initials, price code, and year on the reverse sides.

The reverses of all three miniatures are lined with paper, on which T. M. Whitehead wrote the date (“1856”) and his price code (“£a.o.o”) in ink.

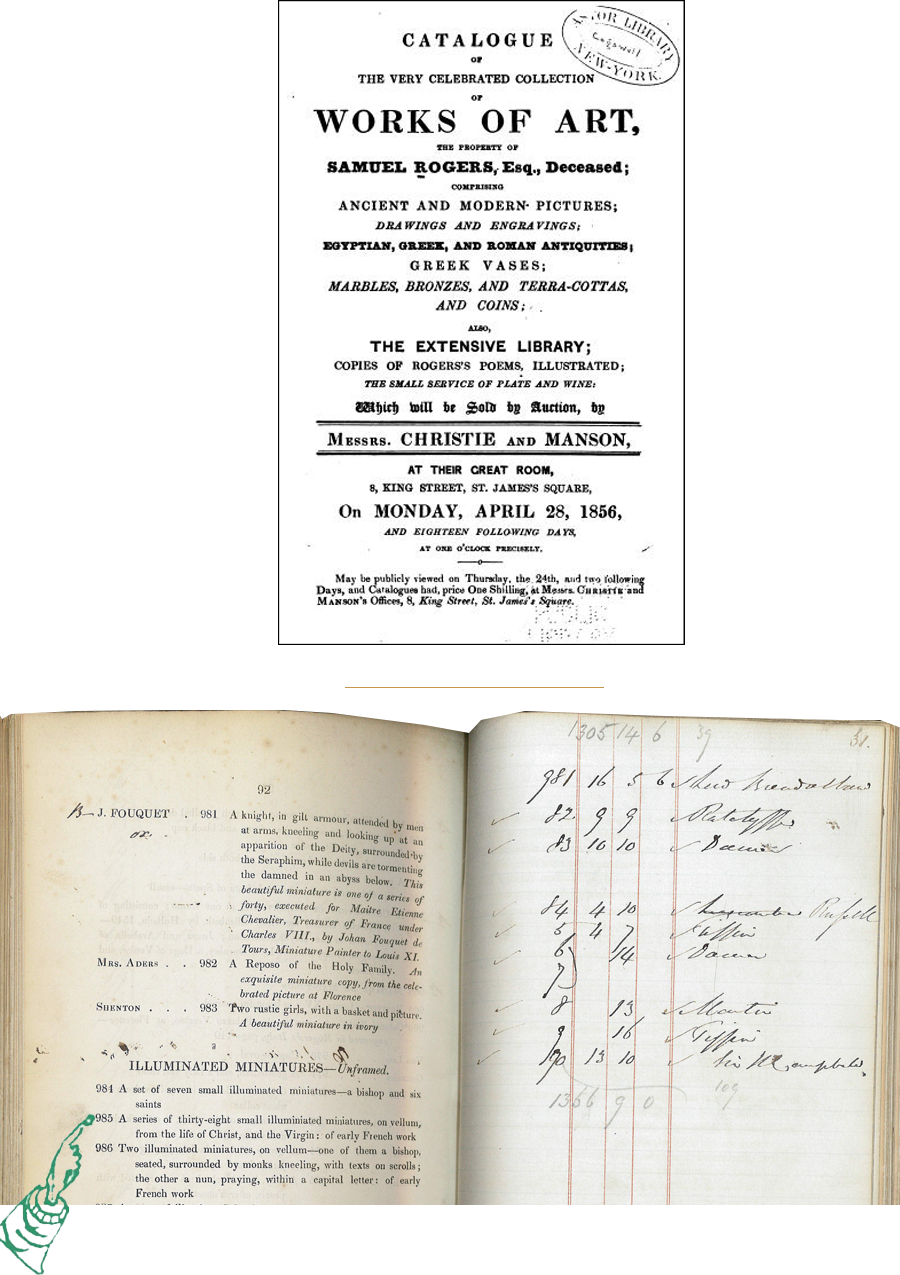

Peter Kidd identified the notes on the reverse sides of the sister leaves at the Free Library as belonging to Whitehead in the latter half of a post to his Manuscripts Provenance blog. He has also generously shared with us his research that identifies the thirty-eight of the sister leaves, including our three, as lot 985 in the 1854 Samuel Rogers in London. The letter “T” is written before the price code, shorthand for Walter Benjamin Tiffin, who sold the miniatures to Whitehead after he had purchased them at the Rogers sale, as confirmed by the Auctioneer's Book.

Title page of the 1856 catalogue of the Samuel Rogers sale (left, image courtesy of Peter Kidd), with our three miniatures part of lot 985, recorded as sold to Tiffin in the Auctioneer’s Book (right, image courtesy of Christie’s Archives)

It is remarkable that we can place these miniatures in the collection of Samuel Rogers (d. 1855), the lauded poet-banker and an early collector of illuminated manuscripts in England.

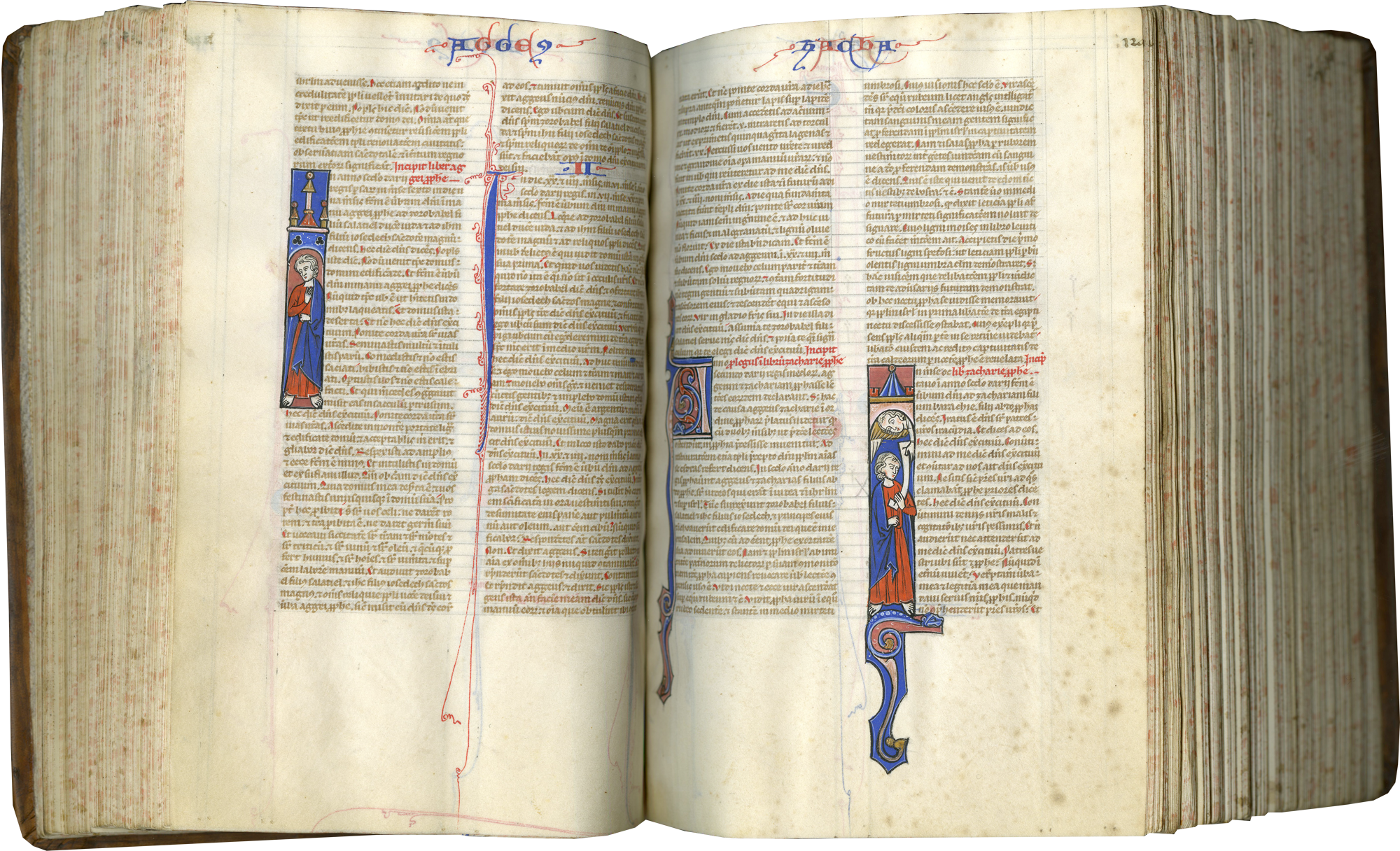

The illuminated Bible historiale was among the “must haves” of the 15th-century upper crust, but it and other translations of the Bible never entirely win out over copies of the Latin Bible known as the Vulgate, which was reformatted and repackaged generation after generation. Among these is the 13th-century Paris “pocket” Bible, like our TM 921.

Les Enluminures, 13th-century Paris “Pocket” Bible, TM 921

In the 1450s the Gutenberg Bible ushered in the new world of printing, revolutionizing the way Bibles were produced. Its success, like the Bible historiale, relied in large part on its colorful pictures and eye-catching decorations added by illuminators in the headers and wide margins.

Historiated initial with Saint Jerome, 1462 Gutenberg Bible, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, f. 1

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”