For Halloween we pulled a “thriller” off the shelf with graveyard mysteries and bloody murder. To set the scene let’s begin in 1170 with arguably the most famous murder to happen inside a church. During evening prayers at Canterbury Cathedral, Thomas Becket was killed by four knights (probably acting on the orders of King Henry II). By all reports it was an awfully grim scene. The victim (Thomas) was regarded as a saint in very short time, thanks to miracles attributed to his relics – including bits of fabric that eager pilgrims had soaked with his blood.

A red glass cabochon evokes the blood of the saint, set in the top of a Reliquary Casket with Scenes from the Martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket, c. 1173-80, Metropolitan Museum of Art (17.190.520)

Of course violence and blood inside the church is never good, but the specter of the murder scene was the bigger problem. As a profaned sacred space the church needed to be reconsecrated through the holy words and actions of the clergy.

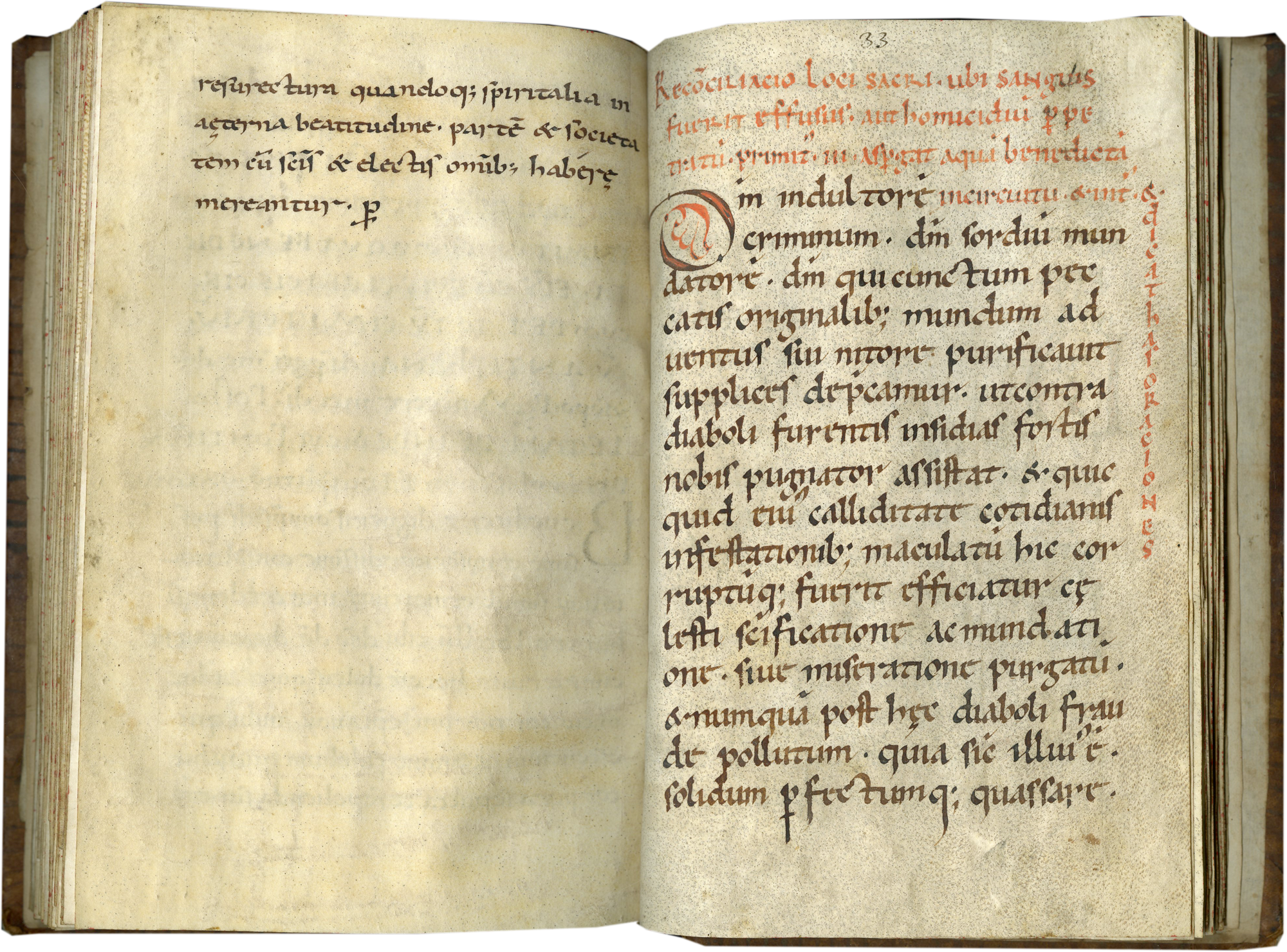

TM 834, “Primitive” Pontifical, Central or Southern France, c. 1040-1075, ff.32v-33

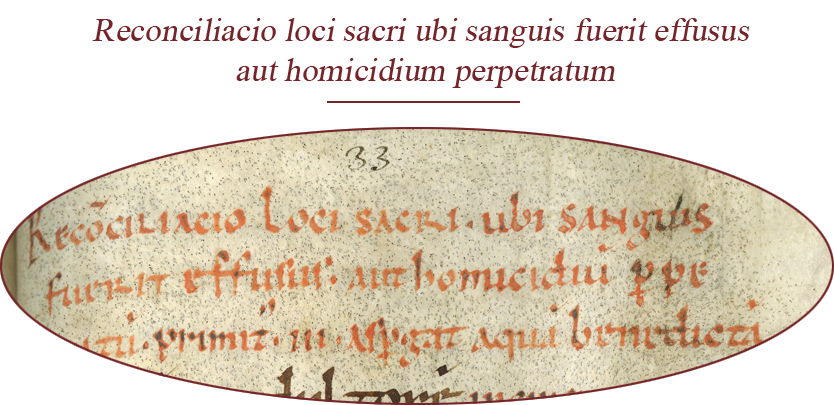

But how? There’s a liturgy for that! One recorded in a special book for the use of priests and bishops: the Pontifical. TM 834, a “Primitive” Pontifical from the late 11th century (c. 1040-1075) copied in Southern or Central France, provides the aptly-named ritual for the “reconciliation of a sacred space where blood was spilled or murder perpetrated” (Reconciliacio loci sacri ubi sanguis fuerit effusus aut homicidium perpetratum).

TM 834, “Primitive” Pontifical, Central or Southern France, c. 1040-1075, f.33, detail

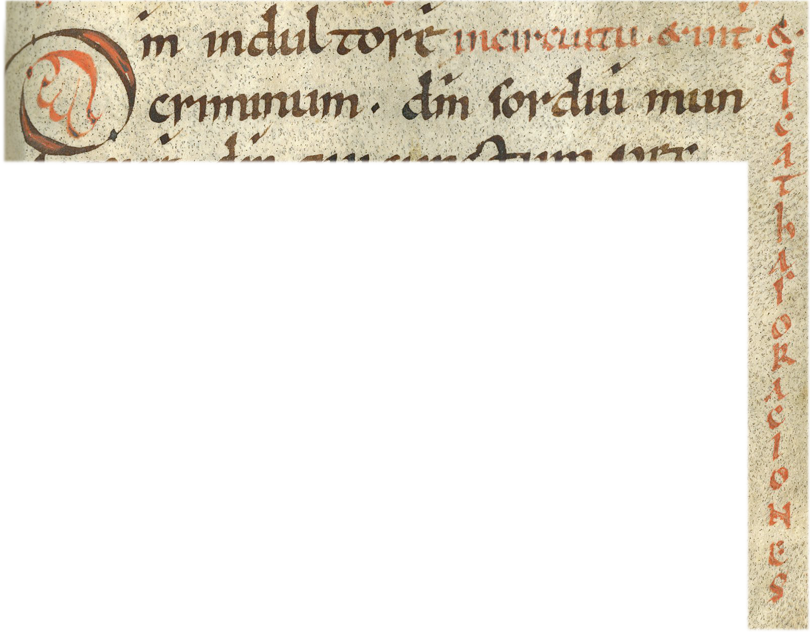

Incredibly, the rubric describing effusions of blood appears to drip down the side of the folio (although this scribal practice was not uncommon if space was limited). A spooky coincidence? We will never know.

TM 834, “Primitive” Pontifical, Central or Southern France, c. 1040-1075, f.33, detail

There are other mysteries, perhaps even the name itself. Why “primitive”? Following in the footsteps of the Sacramentary (a book containing prayers for mass and the sacraments, as well as rites such as the dedication of a church), more descriptive booklets emerged in the seventh and eighth centuries for the use of bishops, eventually codified into the so-called Romano-Germanic Pontifical in the tenth century. At the same time, however, local traditions continued in so-called “Primitive” Pontificals – as in this manuscript, which is comprised of small books (libelli) for specific uses.

TM 834, “Primitive” Pontifical, Central or Southern France, c. 1040-1075, f.31v-32.

Another mystery is the ritual added in empty space on folio 32, written in slightly darker ink, giving the text for the blessing of a cemetery – an intriguing early witness to changing attitudes about places for the dead. In the late eleventh century cemeteries were increasingly seen as be inviolable spaces, offering protection to both the living and the dead. Anyone found guilty of a crime on cemetery ground would face heavy fines or excommunication. The new importance of sacred cemeteries was popularized by Pope Urban II, who consecrated (or re-consecrated) cemeteries as he traveled through France in 1095. The practice, as described here, involved the bishop and his priests singing songs while walking in a circle around a cemetery and sprinkling holy water.

It’s hard to say when it was added, but it was no doubt a handy text for any 12th-century crypt keeper (or bishop).

With eyes open – or maybe peeking through fingers during the scary parts – we have only begun to pry the secrets from the pages of this “Primitive” Pontifical. A full description of TM 834 is available here.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”