We usually try to give our blogs a catchy title. In this case, we didn’t have to try very hard. What could be more intriguing than a book called the Secret of Secrets (in Latin Secretum secretorum)? Everyone likes secrets, and this title also hints at something tremendously important. What would your “Secret of Secrets” be? World peace? Eternal youth? A cure for cancer? The perfect recipe for fried chicken?

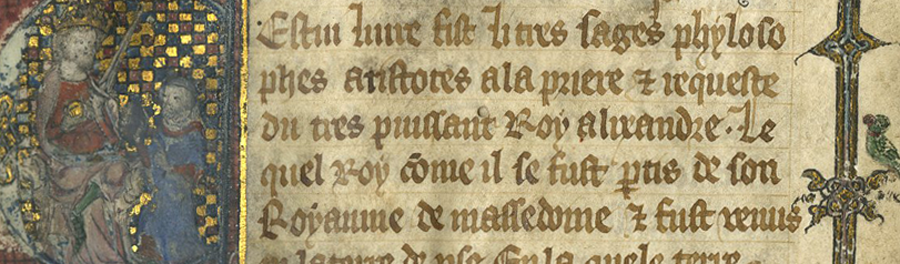

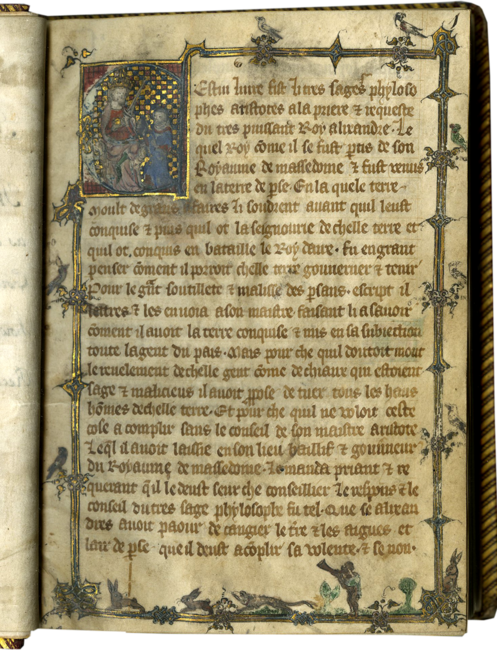

Pseudo- Aristotle, Secret des secrets [Secret of Secrets], anonymous translation. TM 720, f. 1, France (perhaps Arras or Tournai, or Paris?), c. 1300-1320

This text deals with all these topics, in a way (well, maybe not the fried chicken). The Secret of Secrets is written as an extended letter from the Greek philosopher, Aristotle (384–322 BC) to his former pupil, Alexander the Great (356-320 BC), offering a guide to the art of government and correct royal conduct, in the broadest sense, including moral and political advice, as well as information on science and medicine, health regimen, astrology, physiognomy, alchemy, numerology, and magic. Knowledge is power, and this small guide promises to provide the key.

A messenger from Aristotle kneels before Alexander the Great to present this book. TM 720, f. 1

In actuality, this isn’t a text by Aristotle, but rather an Arabic text known as the Kitāb Sirr-al-asrâr (Book of the Secret of Secrets), written sometime before the late tenth century by an anonymous author, and translated into Latin twice during the Middle Ages, first in a shorter version in the twelfth century, and then c. 1230 by Philip of Tripoli. It was truly a medieval bestseller, surviving in many hundreds of manuscripts.

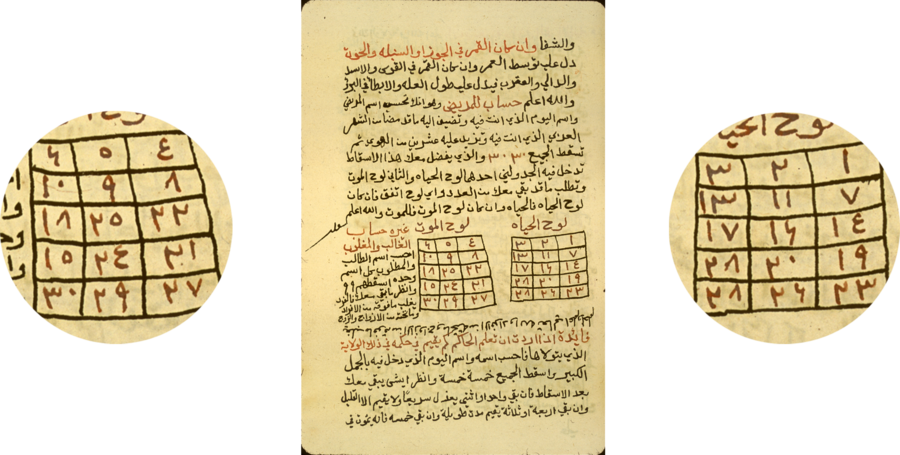

Charts for determining whether a person will live or die based on the numerical value of the patient's name. Kitāb Sirr al-asrār (The Secret of Secrets), dated Rajab 1264 [= 3 June-2 July 1848], National Library of Medicine, MS A 57, f. 7a.

But it was not a text read only by the learned; there are early translations into most of the vernacular languages, including French. Many different translations into French survive. The version in our manuscript – early and known in only four complete copies – is a very faithful translation of the Latin that includes all the scientific advice, medical, alchemical, astrological, and so forth. Most of the other, more broadly disseminated French translations, in contrast, omitted these topics, concentrating only on the moral and political advice to the sovereign – transforming a scientific Latin text into one belonging to the advice books genre known as “Mirrors of Princes.”

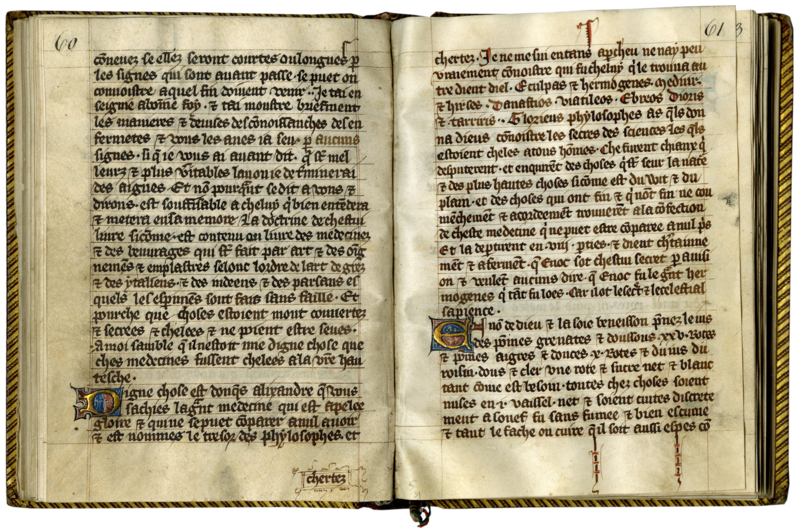

Pseudo- Aristotle, Secret des secrets [Secret of Secrets], anonymous translation. TM 720, ff. 60v-61, France (perhaps Arras or Tournai, or Paris?), c. 1300-1320

In this French translation, one can discover how to make a panacea (the gloria inestimabilis in Latin, here called simply “Gloire” or the treasure of the philosophers) that slows aging and boosts intelligence, learn about the hidden properties of stones and herbs, about physiognomy (assessing character from someone’s outward appearance, especially their facial features), about plants and their connection with astrology, and read the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, treasured by alchemists as providing keys to primal matter and the philosopher’s stone, known to all of us now thanks to the Harry Potter books (for another manuscript that includes a recipe for the philosopher’s stone see our post, Book of Secrets.)

This French translation follows in the tradition of one of the most fervent supporters of the Secret of Secrets, the Franciscan philosopher and scientist, Roger Bacon (c. 1220-c.1292), who accepted it whole-heartedly as a work by Aristotle.

The English philosopher and scientist, Roger Bacon as an alchemist Michael Maier’s Symbola aurea mensae

A second copy of this particular French translation was made for Charles V (1338-1380), king of France from 1364-1380. Charles V was a good king, and a learned one.

The Coronation of Charles V in London, British Library, Cottom MS Tiberius b viii, f. 35

He was the founder of the French Royal library, housed in a tower at the Louvre palace. And he was particularly interested in acquiring the learned works of his day in French. He commissioned Nicole Oresme, c. 1370, for example, to translate four works by Aristotle, the Ethics, Politics, Economics, and On the Heavens.

Scholars once thought he may have commissioned this translation as well – it fits perfectly with his interests.

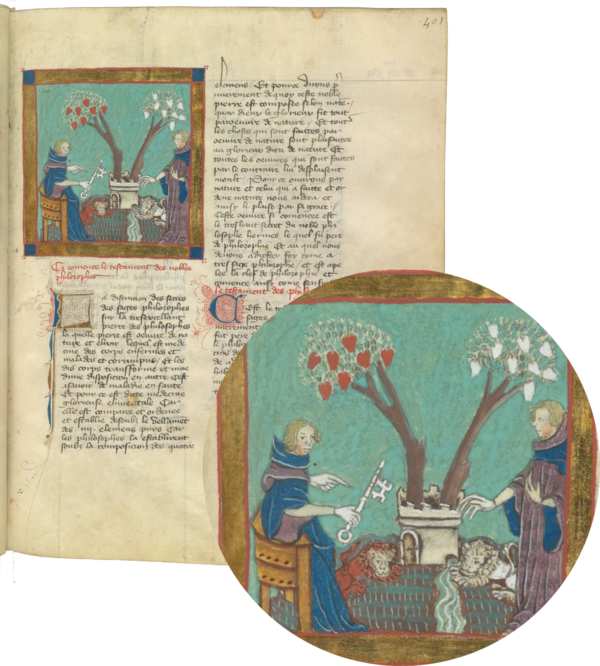

Scientific Miscellany made for King Charles V of France, including a French translation of the Secret of Secrets, Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, MS 2872, f. 401r. (Source: Gallica, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b60002894)

This theory has been put to rest by Professor Catherine Gaullier-Bougassas, who discovered that our manuscript includes the same translation as the Arsenal copy made decades later for Charles V.

Illuminated border, TM 720, f. 1.

We don’t know for whom our manuscript was made. It is small and personal (measuring 157 x 112 mm., or about 6 x 4 1/2 inches), but also very fine, with its lovely illumination, and high quality parchment. Was this the presentation copy made for someone of high rank and wealth who commissioned the translation early in the fourteenth century? It seems very likely. The exact identity of this mysterious person is one secret that has not yet been answered.

TM 720 is one of our newest additions to the Text Manuscripts site, one of thirty-one new manuscripts included in the recent September update. For more, see www.textmanuscripts.com

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.”