“Queen Eleanor” by Frederick Sandys, 1858, National Museum, Cardiff.

Like good parents, we love all our updates equally, but we are particularly excited about the 34 “new” manuscripts that were added to the text manuscripts site on October 1. Here are two of my favorites.

When you think of French literature in the Middle Ages, do you think of Eleanor of Aquitaine (1124-1204) and her daughter Marie, Countess of Champagne (1145-1198) and tales of courtly love? Perhaps you think of Lancelot and Guinevere?

Lancelot and Guinevere, London, British Library, Additional MS 10293, f. 199, detail, Northeastern France or Flanders (St. Omer or Tournai), c. 1315-1325.

That isn’t surprising. When most of us were learning about the development of vernacular literature in France (that is, texts written in French, rather than in Latin) from the end of the eleventh to the thirteenth century, we were taught about the Chansons de gestes (Epics in Old French), the poetry of the troubadours, and, of course, about the stories of courtly love by Chrétien de Troyes (c. 1135-c.1185) and others.

Percival depicted in a fourteenth-century manuscript of Chrétien de Troyes, Perceval ou Le Conte du Graal, Paris, BnF, MS Français 12577, f. 36.

These texts have traditionally been viewed as manifestations of a growing secular culture among the French nobility, a culture that, by definition, was separate from the clerical Latin culture of the church. Or so we once thought. Increasingly, modern historians have come to recognize that contrasting a vernacular, lay or secular, culture, with a Latin, clerical and religious, culture, is too simplistic. Two manuscripts in this update speak to this fact in interesting ways.

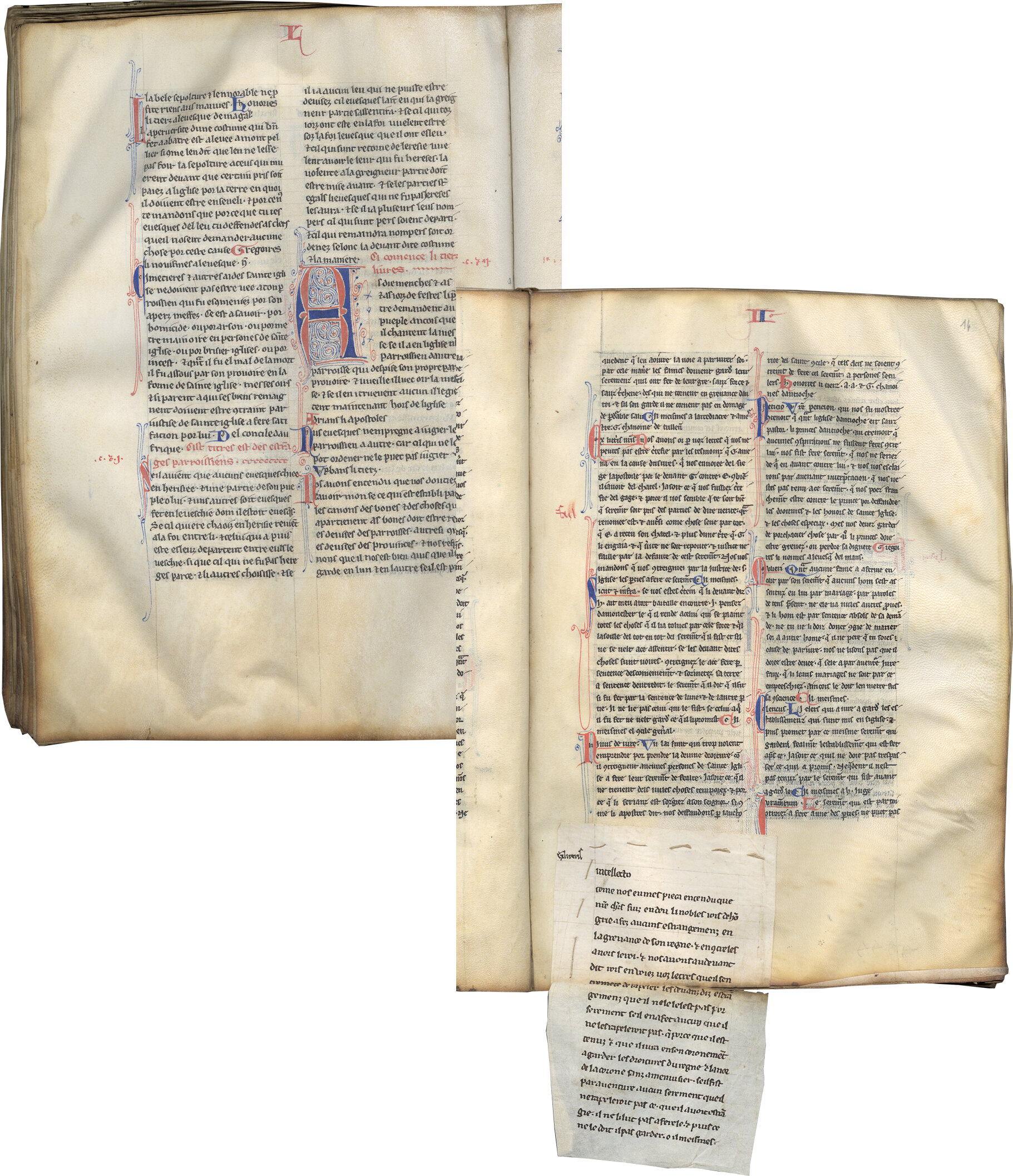

Les Enluminures, TM 1097, Anonymous French translation of the Decretals of Gregory IX, Northern France (Paris?), c. 1250-1275.

Our first manuscript reminds us that vernacular literature in France included far more than tales of knights and ladies. In fact, the text in our manuscript is not literary at all, but rather a French translation of a fundamental text of canon law, the Decretals of Gregory IX (pope from 1227-1241). The Dominican, Raymond of Peñafort (c. 1175-1275) compiled this collection of canon law at the pope’s request to bring Gratian’s Decretum, from the mid twelfth century, up to date. Not surprisingly, there are many, many manuscripts of this fundamental text in Latin. But I was simply astounded by our manuscript, which is a French vernacular translation of a very learned Latin law text.

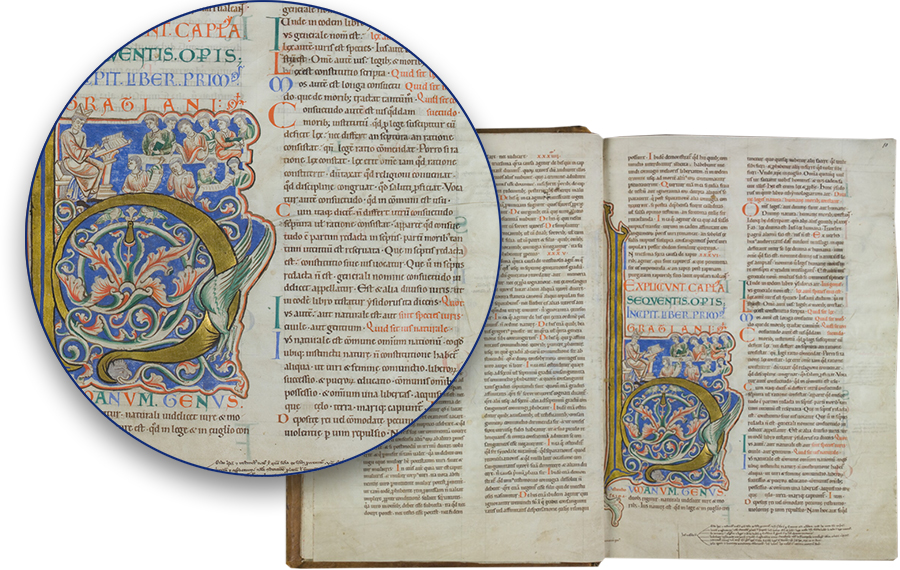

Gratian teaching law, Saint-Omer, Bibliothèque d’agglomération, MS 453, f. 10, Northern France, c. 1163-1176.

There are in fact twelve surviving manuscripts of this text, thirteen if you count our manuscript, which is incomplete, and one other fragment. Certainly, canon lawyers, high-ranking clerics, and even law students at the universities, knew Latin. Why then, was there a need for this text in French? To understand this, we need to remember that canon law or the law of the church did not only apply to the clergy. Many aspects of the daily life of the laity, from marriage to death (cases involving wills were adjudicated in ecclesiastical courts) were governed by the rules of canon law.

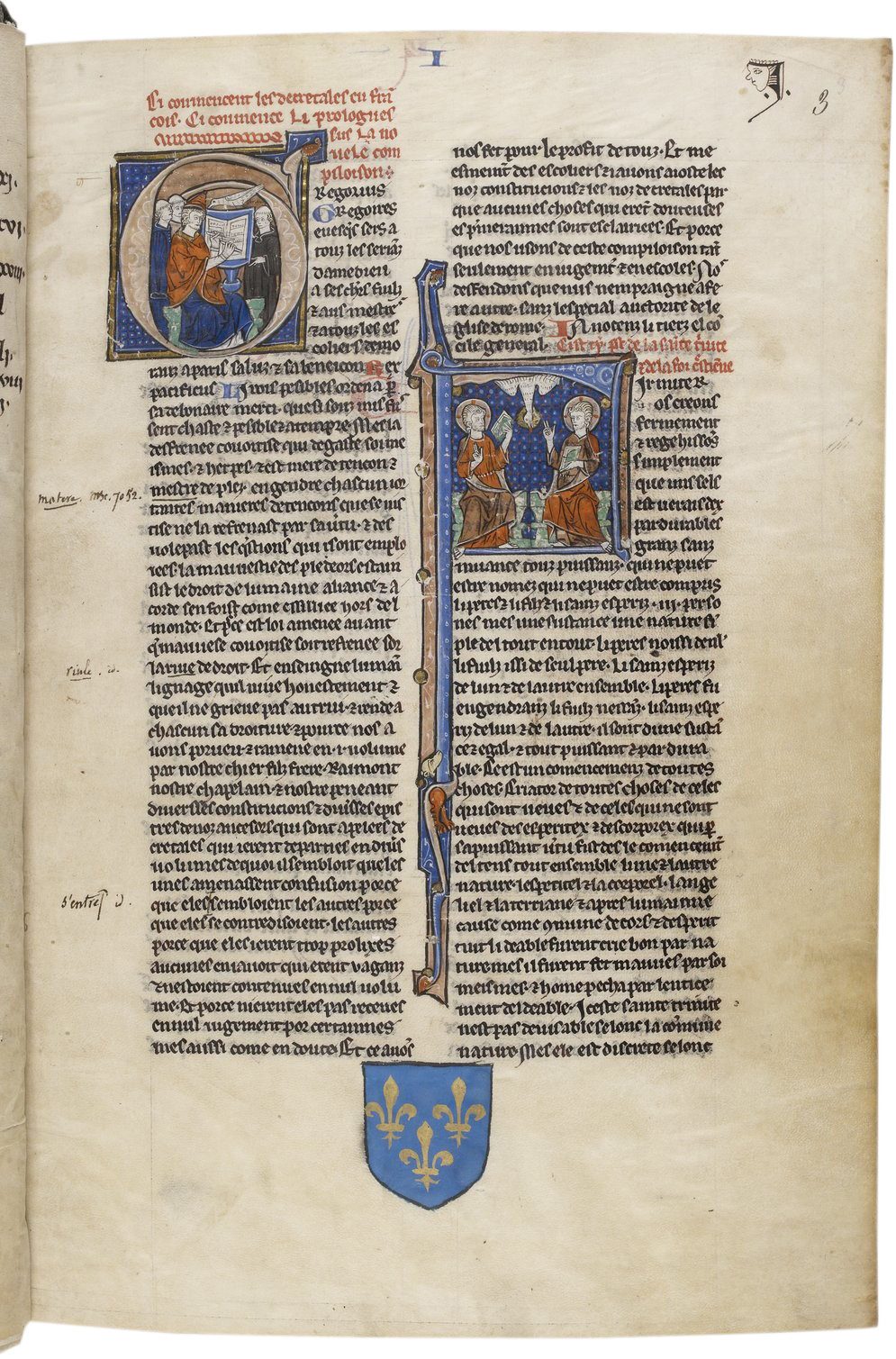

A copy of the Decretals in French from the Royal Library, Paris, BnF, MS fr. 493, f. 3.

It is of course, unlikely, that “ordinary” people read the Decretals in French. We do know, however, that a remarkable ten copies of this translation were found in the French Royal Library in the fourteenth century, evidence that this French translation was embraced by secular rulers who needed to understand the laws governing the church and the clergy (and important aspects of the lives of the laity as well), and to understand which jurisdictions were proper to the church and which were proper to the state.

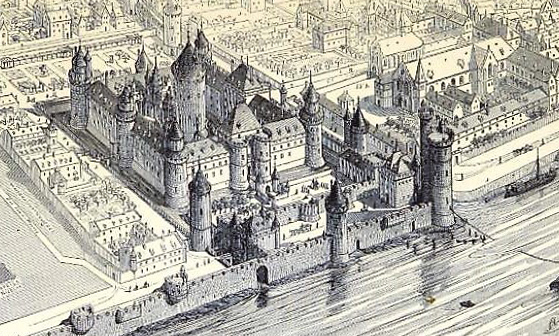

The Louvre in Paris, site of the first royal library, founded by King Charles V (1338-1380).

This translation was not created in a vacuum. The first complete translation of the Latin Bible in western Europe, the Old French Bible, dating c. 1220-1260, may have been sponsored by Blanche of Castile (1188-1252) and her son King Louis IX (1214-1270), continuing a tradition of religious texts in French that started in earnest in the twelfth century. Moreover, other important legal texts were translated into French in the thirteenth century, including Gratian’s Decretum (surviving in one manuscript, now in Brussels), and Justinian’s Institutes. In short, let’s remember that when we think of the blossoming of French in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, we need to think much more broadly than of tales of Lancelot and Guinevere.

Les Enluminures, TM 1090, Vita et transitus Hieronymi (Life and death of St. Jerome), f. 1v, Central Italy, c. 1440-1460.

Our second manuscript, TM 1090 is, in a way, the inverse of the French translation of the Decretals, since it includes a treatise on courtly love in Latin within a serious religious miscellany. The first three texts in this book are all about the death and miracles of St. Jerome (345-420). Purporting to be by contemporaries of Jerome, Eusebius of Cremona (d. 423), St. Augustine (354-430), and Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 315-c.386), in actuality they were probably written in the late thirteenth century or fourteenth century to encourage the veneration of Jerome (his relics had recently been transferred to Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome). Whether they are considered pseudepigrapha or deliberate forgeries created with the intention to deceive, these texts were very popular and survive in numerous manuscripts and early printed editions; they could be a subject of an entire blog all by themselves.

The Life and Miracles of St. Jerome were extremely popular. There is a second example on our text manuscripts site, Les Enluminures, TM 656, from Northern Italy, c. 1440-1470.

The final text in this manuscript, however, seems, at least at first, to be quite a departure. De amore, or About Love by Andreus Cappellanus, or if you like, Andrew the Chaplain, has traditionally been presented as the treatise on courtly love, the very ideas that lay behind so much of the literature circulating among the French nobility in the second half of the twelfth century. It may surprise you, therefore, that it was written not in French, but in Latin. We know almost nothing for certain about the author, but given his name, he was clearly a cleric, perhaps associated with the court of Henry the Liberal (1127-1181) and his wife, Marie of France (1145-1198), countess of Champagne and Troyes, the daughter of Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204). Alternatively, he may have been writing in Paris at the beginning of the thirteenth century at the royal court.

Seated woman, possibly Marie de France, Paris, BnF, MS Français 794, f. 27, France (Champagne), c. 1230-1240.

The question of the intended audience for De amore has been much debated. Our copy of this text includes just the third book, De reprobatione amore or On the Condemnation of Love (the book that has challenged modern interpreters made uneasy by its rather venomous misogyny). Its presence here as part of a miscellany that includes texts about Jerome lends support to the suggestion that his audience was primarily his fellow clerics.

Les Enluminures, TM 1090, The beginning of On the Condemnation of Love, f. 79.

One last note. This manuscript survives in its original binding, with flyleaves from two fourteenth-century documents. These documents can be localized based on their references to the city of Rieti (about seventy kilometers northeast of Rome), to the Benedictine monastery of San Salvatore Maggiore, and to the lord of Rocca Sinibaldi (a town not far from Rieti). Rieti and its archives were the subject of extensive research by the celebrated medievalist, Robert Brentano, in A New World in a Small Place: Church and Religion in the Diocese of Rieti, 1188-1378, Berkeley, 1994.

Les Enluminures, TM 1090, fourteenth-century document from Rieti, a small town about seventy kilometers northeast of Rome.

Our latest update includes many more manuscripts, including (to choose a few more) a first-hand report of the sermons of St. Bernardino of Siena (TM 999), a stellar array of humanist texts (Ludovico de Guastis, Epitome of Pliny’s Natural History, TM 1098), and the fictional letters of the tyrant Phalaris, Epistole Phalaridis, TM 1081); and a membrane from an illuminated Universal Chronicle roll (TM 1139).

You can see complete descriptions and images of the manuscripts from this update on www.textmanuscripts.com.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!