Let’s play a game. What do you think of when you hear, “Bible,” and “Thirteenth Century”? For many readers of this blog these phrases will immediately conjure up images of that amazing invention, the thirteenth-century portable or “pocket” Bible.

Here is an unusually small example of the genre which includes the complete text of the Bible from Genesis to the Apocalypse in 512 folios. The dimensions of each page, which were trimmed severely by a modern binder, are 113 x 72 mm., with the dimensions of the written space (or justification) only 88-85 x 59-57 mm. It is copied in astonishingly small script with 49-47 lines per page.

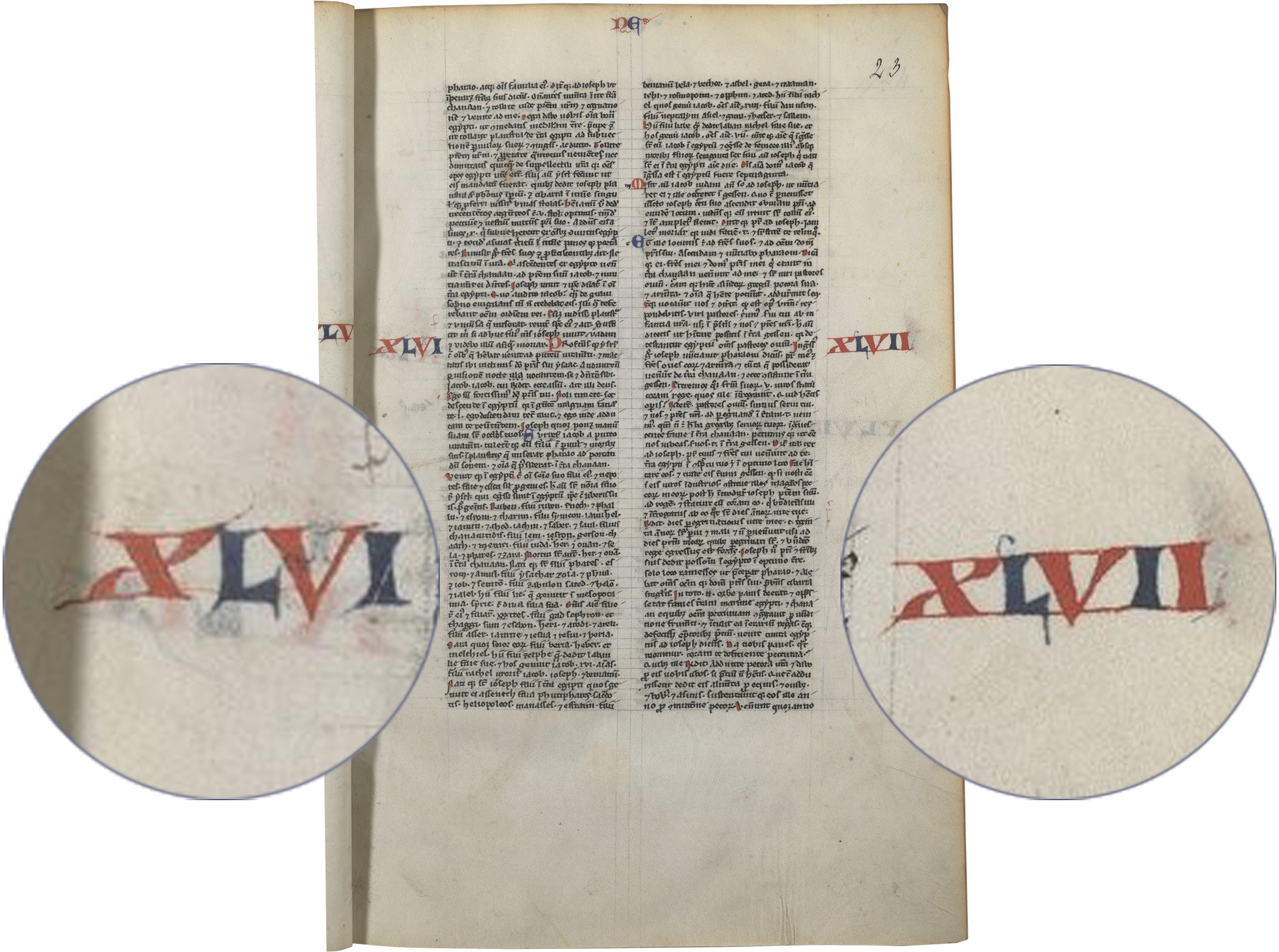

TM 941, Pocket or Portable Bible, Northern France (Paris?), c. 1230-1250, ff.228v-229

Now what do these phrases, “Bible” and “Twelfth Century” conjure up in your mind?

Perhaps you thought of Glossed Bibles, like this early example that includes the book of Job, copied in larger script in the center of each page, accompanied by commentaries on the text copied in a much smaller script in the margins and between the lines.

TM 877, Glossed Job, Northern Italy, c. 1125-1140.

The Bible and its Gloss gave readers – often teachers and students of the Bible – access to the biblical text and relevant commentaries in one convenient location. The Ordinary Gloss was not a text compiled, or even thought of, by a single author, but was rather the result of a long process over the course of the twelfth century that gradually grew to include the complete Bible. (Although one should note that the idea of assembling a set of glossed books that included the entire Bible seems always to have been the exception rather than the rule; glossed books of the Bible usually circulated independently, and included only a single book of the Bible, or a few related books).

Alternatively, you may have thought of one of the great Romanesque Bibles that graced the monasteries of twelfth-century Europe. So many examples to choose from. The Parc Abbey Bible, copied near Leuven in the diocese of Liege in 1148 is an excellent example; it is a three-volume Bible measuring 435-430 x 300 mm. Here is the glorious painted page found at the beginning of Genesis,

London, British Library, Additional MS 14788, The Parc Abbey Bible, Genesis

And here is a more representative opening which includes the biblical text with the beginning of the Epistle of St. James,

London, British Library, Additional MS 14790, The Parc Abbey Bible, Epistle of St. James

Last question: what do you think of when I say “Bible” and “c. 1200-1230”?

That is, of course, pretty specific, and thus more difficult. But I sincerely hope the image of a thirteenth-century portable Bible did NOT flash into your mind, since true portable Bibles, copied on their distinctive tissue-thin parchment, date only after c. 1230 (the very earliest example of Bibles copied in this format may date to very late 1220s).

Our subject today is one type of Bible from the first three decades of the thirteenth century––transitional Bibles with roots in the twelfth century, but which also point toward the new Bibles of c. 1230 and later.

Our first example was copied in Paris very early in the thirteenth century. It includes the complete Bible in one volume of 337 folios, measuring 380 x 255 mm. Here is the beginning of Genesis, illustrated (for some reason not clear to me) with amusing vignettes of animals playing musical instruments instead of the customary images of the creation,

Paris, BnF, MS lat 16747, Genesis initial in an early thirteenth century French Bible.

French Bibles from this period (in particular a special textual group called the Proto-Paris Bible, although we are not going to talk about text today) have been discussed in the scholarly literature. Like most Bibles from after c. 1230, they include the complete Bible in one volume. Their size varies; many are still rather large, but they are nonetheless smaller than most twelfth-century monastic Bibles (representative examples range in size from 480 x 300 to 260 x 190 mm.)

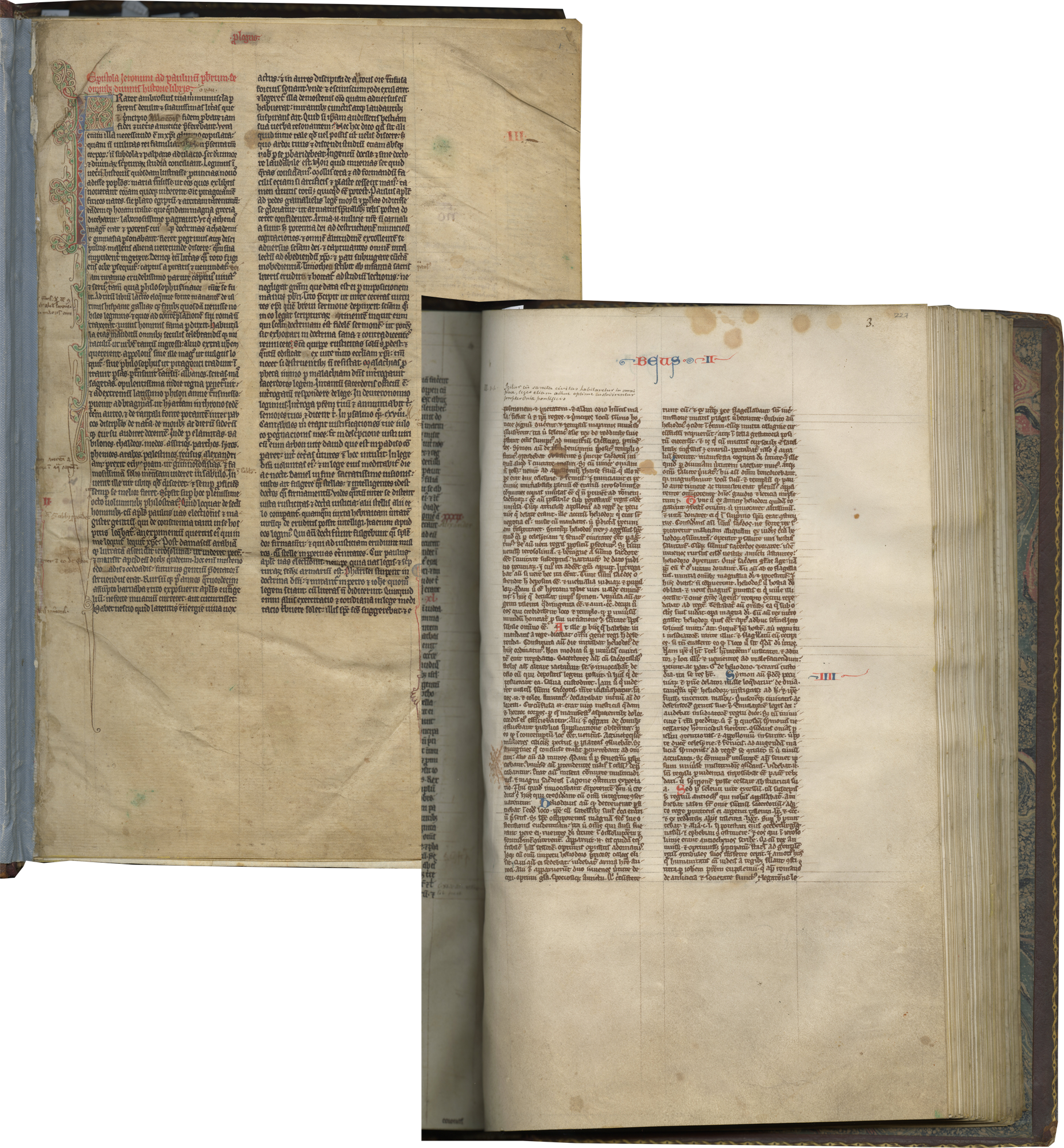

In contrast with the French examples, English Bibles from this period have scarcely been studied at all, but a preliminary survey suggests that Bibles copied in both England and France share a number of common characteristics. Here is an English example, also in one large but fairly manageable volume, measuring 350 x 240 mm.,

TM 973, Latin Bible from England, c. 1220-1230; 1230-1240, f.26

One characteristic of these early thirteenth century Bibles is the reduction of the size of the script and the amount of space between the lines, which led to a marked reduction of the size of the written space on the page and a corresponding increase in the size of the margins. Many of these Bibles, in fact, include glosses copied in the margins (not the complete Gloss, but the link to glossed Bibles is nonetheless an important one).

TM 973, Latin Bible from England, c. 1220-1230; 1230-1240, f.5v

Marginal glosses were added to this Bible very early in its history (although most systematically at the beginning, suggesting perhaps that the original owner began the task of adding commentary, but tired of it quickly).

The chapters in Bibles from this time period are another feature that reveals their transitional nature. The chapters still used today in modern Bibles are found (with very few exceptions) in medieval Bibles dating after c. 1230. Before that, Bibles were divided according to many different systems of chapter divisions. Bibles copied in the first three decades of the thirteenth century often include two systems of chapter divisions.

TM 973, Older and modern chapter divisions in a Bible, England, c. 1220-1230; 1230-1240

Many of the biblical books in our English Bible are divided into older chapters, each beginning with one-line initials, set within the line of text, and in most cases, numbered in small red Roman numerals right before the initial (that is inserted within the line of text). Modern chapters are marked in the margins, usually in red Roman numerals. In the detail above, the chapter numbered “xxxi” within the line of text is an older chapter division; below it you can see the chapter which was numbered “xxxii” (also an older system of chapters), and in the margin a larger “XIV,” the modern chapter.

In this French Bible, dating about the same time, c.1210-1230, the older chapters begin with one-line initials, but are unnumbered; the modern chapters are numbered in the margins with bold red and blue Roman numerals.

Paris, BnF, MS Lat 15475, Two systems of chapter in a Latin Bible, Paris, c. 1210-1230, f.23.

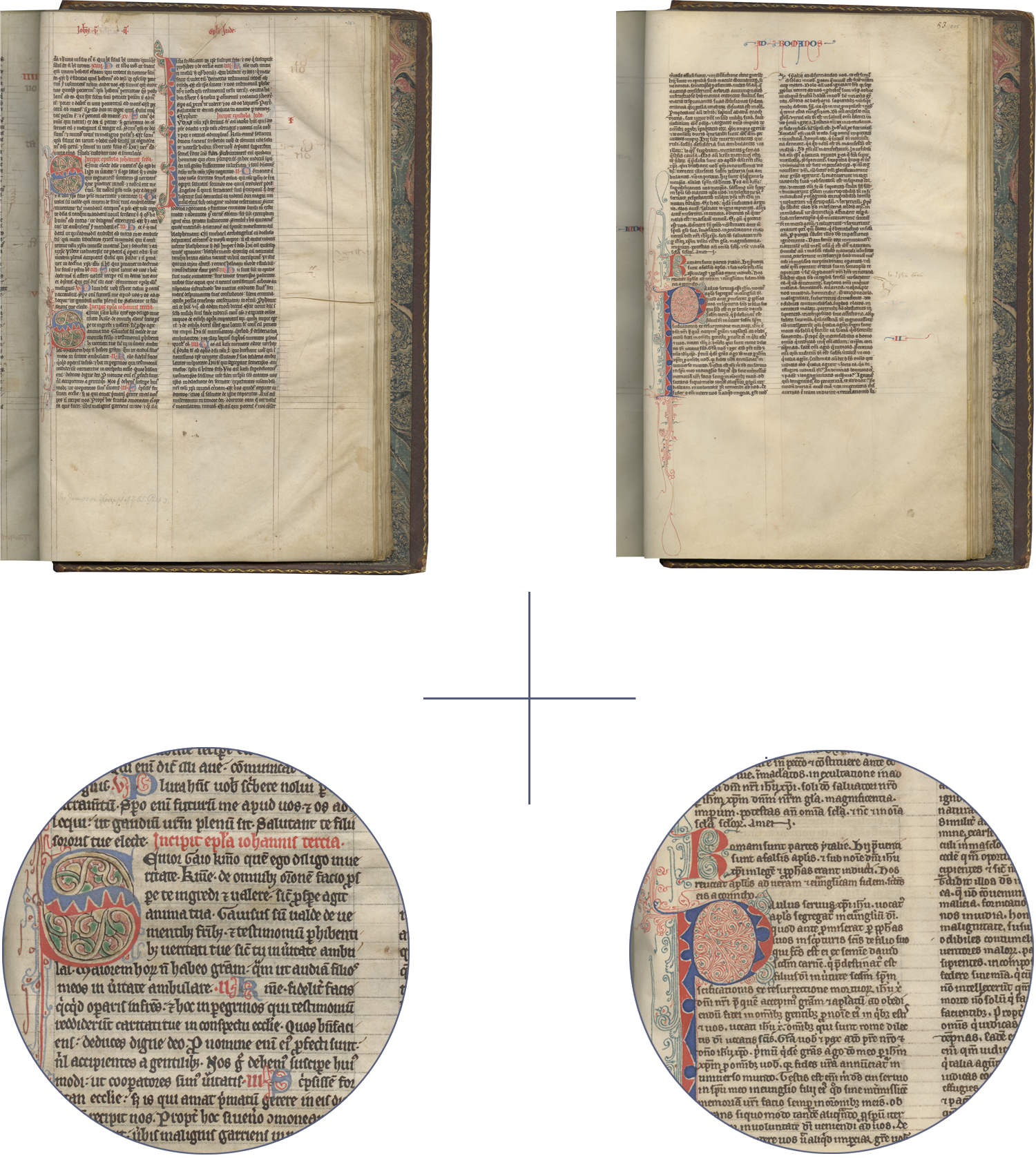

TM 973 is a complicated volume. Compare these two pages,

TM 973, Latin Bible from England, two contrasting folios in the same English Bible

The script and decoration on these two pages are completely different. The style of the penwork initials in fact suggests the page on the left can be dated c. 1220-1230, and that on the right c. 1230-1240 (although both scribes begin writing on the top ruled line, often, but not always, an indication of a date before c. 1230).

The text of our Bible (TM 973) includes two discrete sections; the earlier section (or Bible 1), on ff. 1-226v, includes Genesis-1 Maccabees 11:35, and ff. 280-303v, with part of the Catholic Epistles (beginning with 1 Peter), Pauline Epistles, and the Apocalypse, and the distinct, probably later section, on ff. 227- 279v, beginning with 2 Maccabees 3:1, and continuing with the New Testament, arranged Gospels, Acts, Catholic Epistles, Romans, and 1 Corinthians, ending imperfectly at chapter 9:3.

TM 973, Latin Bible from England, f.1 and f.227

This is extraordinarily difficult to explain. Perhaps this Bible was damaged very early in its history and repaired? Alternatively, was this Bible assembled from two damaged Bibles, similar in size and format, at some point in its history before it was bound in the eighteenth century? Note that there is still some text missing (one quire in Bible 1 with part of Job and the Psalms, and the end of 1 Maccabees and the beginning of 2 Maccabees, since Bible 2 does not begin exactly where Bible 1 leaves off), and part of the biblical text is found twice (namely 1 Peter-Jude, Romans, and the beginning of 1 Corinthians). Any suggestions? Comments are welcome (contact me at lauralight@lesenluminures.com).

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!