The end of summer brings a return to school. With it, there is a renewed focus on DEI or DEAI, which has become over the last several years a central concern of institutions of higher education in the United States. Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, Inclusion.

This string of initials and the acronym they form helps define who is hired, who is admitted to school, and even what they study. DEAI initiatives also ask us to think differently about building collections and, regarding medieval manuscripts, prompt us to dig deeper into new perspectives that enliven how we look at the past.

Seeing the Middle Ages as an era of white Christian men who lived a cloistered life in monasteries, sharing their thoughts (mostly about religion) in arcane Latin treatises, is mostly outmoded.

Cartoon from The New Yorker (November 7, 2022 Issue)

Many other voices have emerged in scholarship over the last several decades, the voices of townspeople, merchants, students, women, homosexuals, lesbians, the poor, the non-Christians (including Jews and Arabs). We are cognizant that these voices spoke and wrote in numerous other vernacular languages not just Latin. Some of these voices belong to individuals with access to a world well beyond the geographic confines of Western Europe. We at Les Enluminures take pride in teasing these voices out of the manuscripts we describe and sell, and you may be surprised at how many of them help us see the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in a new light. That is the subject of this short blog, which focuses on women.

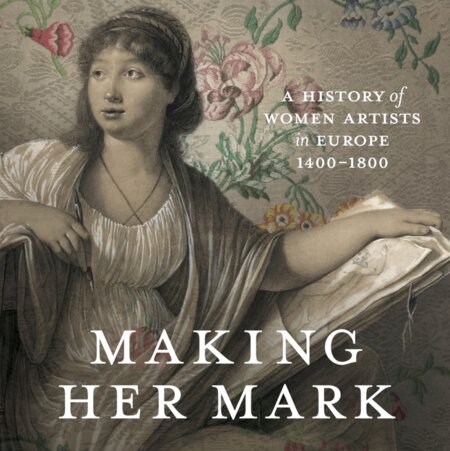

Recovering the voices of women in the Middle Ages is a timely subject. We await eagerly the exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art “Making her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe 1400-1800” (October 1, 2023 to January 7, 2024), an exhibition that will then travel to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto.

For those interested in the history of studies on medieval women artists, it is worth remembering the seminal essay by the then-Keeper of Manuscripts at the Walters Art Gallery (now Museum) in Baltimore, Dorothy Miner, published posthumously nearly fifty years ago in 1974 called “Anastasia and her Sisters: Women Artists of the Middle Ages.” If I may be allowed a little autobiographical diversion, I accepted my first position as a professor at Johns Hopkins in March 1973 in the hopes of working closely with Ms. Miner, but alas she died in May (my position began only in September). At present, we have no women artists represented (knowingly) in the inventory of Les Enluminures. But we have many manuscripts that give women a voice in other ways.

Take Saint Jerome (d. 420 AD), for example. This erudite early Christian Church Father read three ancient languages and is most celebrated as translator of the Vulgate. We always see him in his study pouring over his books, his faithful lion, from whose paw he extracted a thorn, curled up at his feet.

Colantonio (Niccolò Antonio, active in Naples c. 1440-1470), Saint Jerome in His Study, c. 1445, oil on panel. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

But Jerome is also famous for his concern for women and well-known for having many women followers. Two of our manuscripts give voice to Jerome’s women. One of these women, Julia Eustochium, the daughter of a Roman senator, committed her life to perpetual celibacy.

Francisco de Zurbarán (Spanish, 1598-1664) and Workshop, Saint Jerome with Saint Paula and Saint Eustochium, c. 1640/1650, oil on fabric. The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

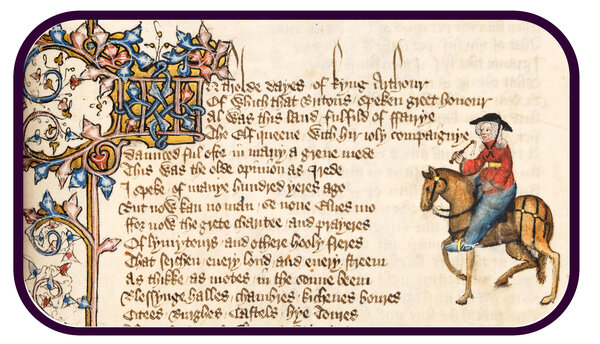

Following Jerome to Egypt, and then eventually to Palestine and Bethlehem, Eustochium founded monasteries in the Holy Land. Our manuscript (TM 559) includes the early monastic rule for female convents that medieval audiences believed was by St. Jerome. The manuscript dates a full millennium after Jerome and Eustochium lived, attesting to the persistence of his ideas well into the Renaissance. Note that one of the texts in our manuscript, the Adversus Jovinianum (Jerome’s position on virginity over marriage) is the very text that the Chaucer’s Wife of Bath inveighs against, additional evidence for Jerome’s enduring readership.

The Huntington Library mss EL 26 C 9, Geoffrey Chaucer, The Ellesmere Manuscript (Canteburry Tales), ff. 72r, an illustration of the Wife of Bath.

In English, illuminated manuscript on parchment. England, c. 1400-1410

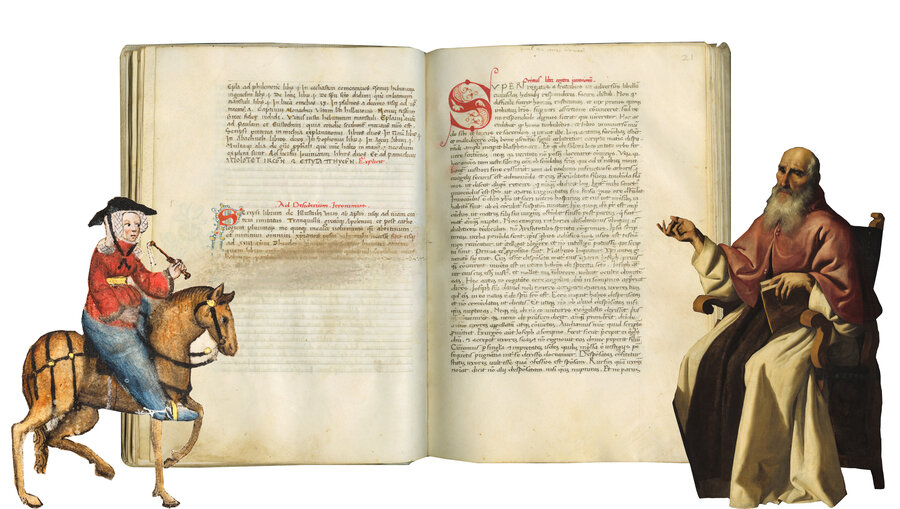

Les Enluminures TM 559, Pseudo-Jerome, Miscellany, ff. 20v-21r. In Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment. Northern Italy, c. 1450-1500.

Here on ff. 21r is the incipt of Primus liber contra iuvenianum

Another of Jerome’s patrician women, Furia, is the subject of a second manuscript (TM 935), Letter LIV (On the Duty of Remaining a Widow). Following the death of Furia’s husband, Jerome urges her not to remarry, instead to care for her children and her aging father. What is of special interest in our copy is not only its late date, c. 1500 (again a millennium after Jerome and Furia lived), or its original Renaissance velvet binding, or its published frontispiece by an important Renaissance illuminator (the Master of Spencer 6), or even its unique copy of an otherwise-unknown French translation, but one of its earliest owners. It was likely made for a noble-born widow of the French court, Anne de Polignac, who is pictured as a sort of modern-day Furia in the prefatory illumination dressed in mourning as she receives a bound copy of Jerome’s letter.

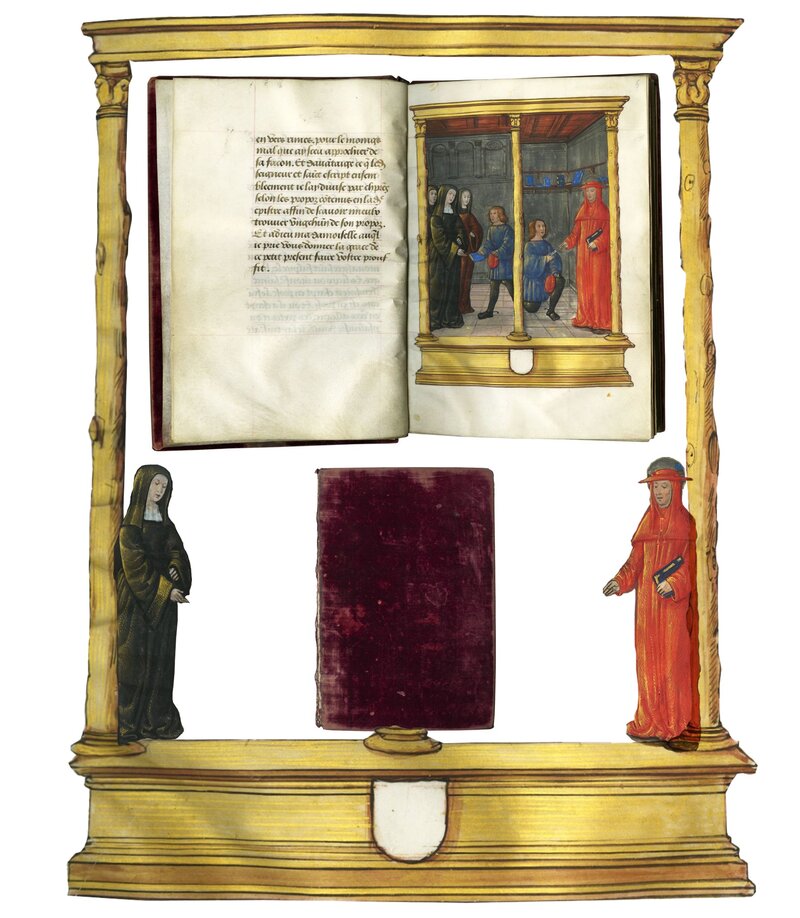

Les Enluminures TM 935, Jerome, Letter LIV To Furia (To Furia, On the Duty of Remaining a Widow), in the translation by Charles Bonin, ff. 4v-5r (above) with explicit of the translator's Prologue and frontispiece, and original Renaissance velvet binding (below).

In French, illuminated manuscript on parchment. Frontispiece painted by the Master of Spencer 6. France (likely Bourges), c. 1500-1510

Like the manuscript of Jerome’s Letter to Furia, what women owned and read offers a window into their lives. I especially like this printed Book of Hours (TM 216BOH). Books of Hours are a mainstay of late medieval readership, owned by men and women, nobles and merchants, and Paris was the center of their production. Given as dowries to the newly married, used to teach children to read, passed down from mother to daughter, and prefaced by the ubiquitous picture of the Virgin Mary reading as a model for women.

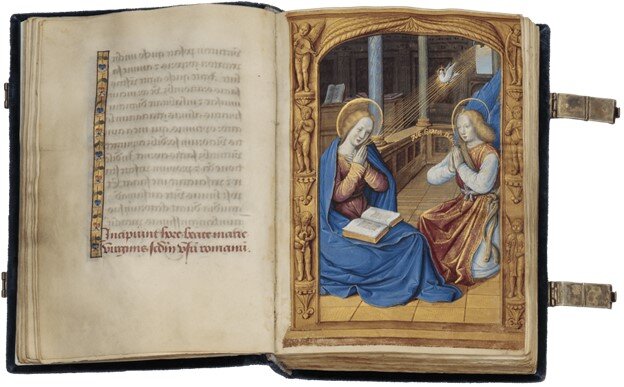

Les Enluminures BOH 80, The “Signed Hours” (Use of Rome), ff.25v-26r, Annunciation.

In Latin and French, illuminated manuscript on parchment. Miniatures by “Jean of Tours” of the Workshop of Jean Poyer and another illuminator. France, Tours, c. 1490-1500

Books of Hours are often thought to represent a sort of rom-com for a late medieval female audience. This is not true. Books of Hours were owned by everyone. This one, however, was indisputably owned and used by a woman. In three separate places in the text Pernette (or Pernaitte) Deloisy (or de Loisy) signed her name.

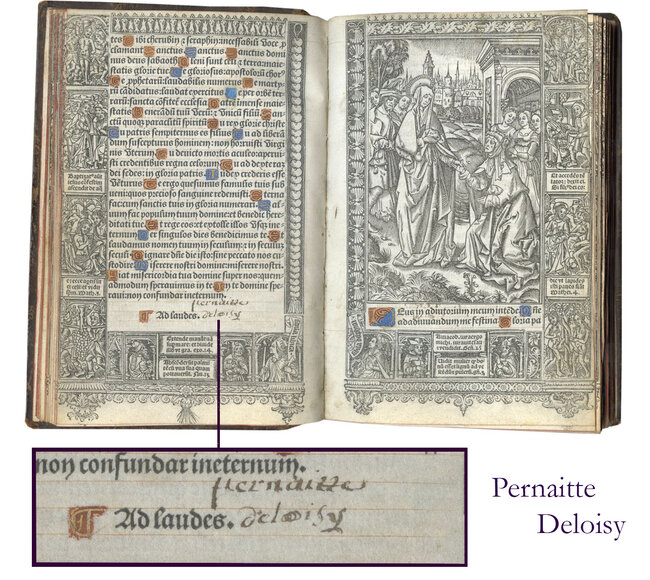

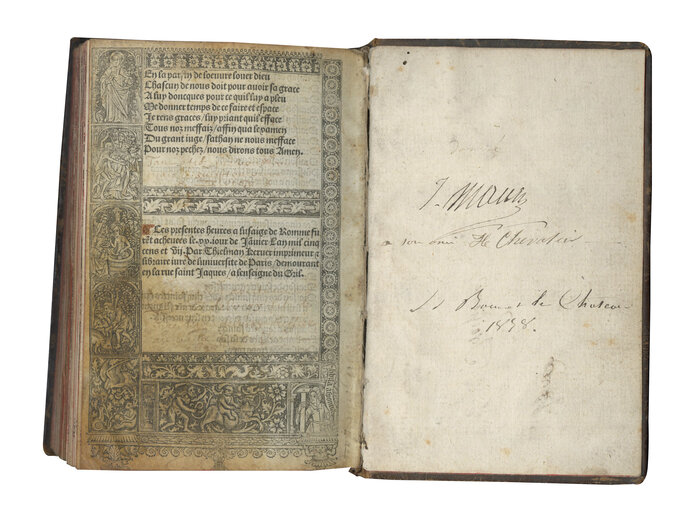

Les Enluminures TM 216BOH, Printed Book of Hours (Use of Rome), ff. c5v-c6r (above) and ff. n4v (below), with autographs "Pernette (or Pernaitte) Deloisy (ff. c5v, ff. n4v)" and colophon of the printer Thielman Kerver dated January 20, 1507 (ff. n4v).

In Latin and French, printed on parchment. With seventeen full-page metalcuts, one large woodcut, Kerver’s printer’s mark, forty-four small metalcuts, and full borders on every page with figurative decoration by the Master of the Très Petites Heures of Anne de Bretagne and Jean Pichore. Paris, 1507

We don’t know who Pernette was, but by marking her book at significant junctures of the text she signaled that it belonged to her – and that she was reading it. The German-born Thielman Kerver active in Paris was the very successful printer of this imprint, and he was to continue his business for another 15 years until his death, when his wife Yolande Bonhomme, the daughter of an important printer’s family (Pasquier Bonhomme), took over his enterprise to become the most successful female printer in Paris, printing numerous editions of Books of Hours. She died only in 1557.

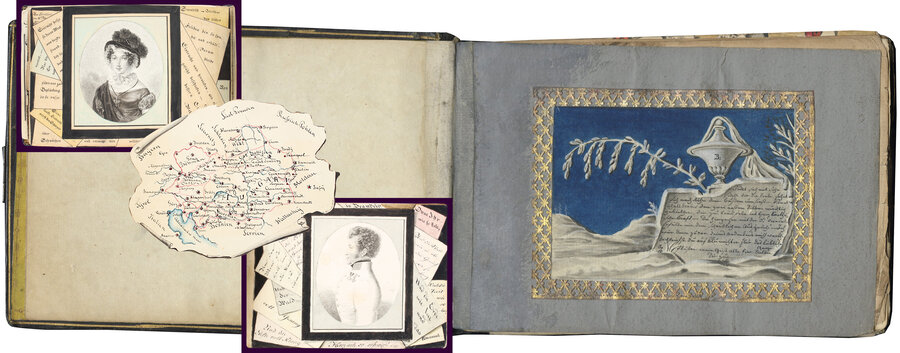

We at Les Enluminures are interested in the voices of women throughout history, including today, and I want to conclude with two examples that post-date the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the primary areas of specialization of Les Enluminures. The genre of Album amicorum (“friendship albums”) is typically male. Universities, until the twentieth century, were for the privileged, mostly wealthy, white, male students, and these men carried with them and passed around little books to be inscribed and drawn in by their friends, also usually male. As far as I know, this album is unique, and a little anachronistic (TM 1246), for it’s not a student album. Rather it records an exchange only between a husband and wife. Every year without fail for thirty years, Emanuel, a Bohemian general, wrote poems or love letters to his wife, Caroline, on her birthday. In response, Caroline sometimes added short notes and annotations. It also includes illustrations.

Les Enluminures TM 1246, Emanuel von Bretfeld zu Kronenburg (1774-1840), Album Amicorum prepared for his wife, Caroline, ff. 1r (watercolor representing a snowy landscape), ff. 39r (detail, map showing the towns Emanuel visited up until 1822 and the battles in which he had participated), ff. 40v-41r (portraits of Caroline and Emanuel).

In German, Italian, French, illustrated manuscript on paper

Varaždin, Ofen, Prague, Brandeis, and Verona, 1810-1840 (dated)

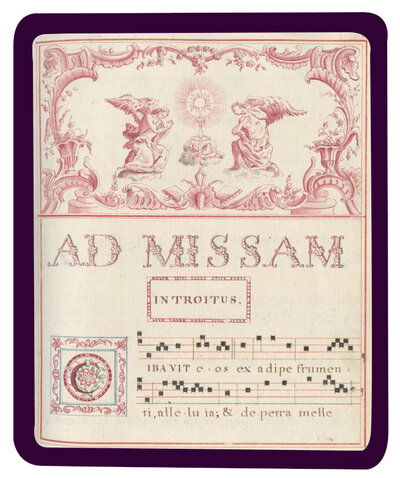

A final example, dating just a little before the Album, is a luxurious music manuscript very likely written and illustrated for Therese-Lucy, a countess and one of the closest friends of Marie-Antoinette Queen of France (TM 1232).

Les Enluminures TM 1232, Officium Corporis Christi (Office of Corpus Christi), p. 81 (detail), implicit of Ad Missam.

In Latin, decorated manuscript on paper with musical notation. Copied and decorated by Ferdinand Boitel. Northern France (Laon), c. 1780-1782

Marie-Antoinette owned a similar manuscript by the skilled calligrapher (“maître ecrivain” or master scribe he was called) Ferdinand Boitel. Its gold-tooled binding and countless pen-drawn images of hamlets, landscapes, waterfalls, vases, flowers, birds, etc. remind us of the continuing fascination with manuscript production centuries after Gutenberg, a fascination for which women’s patronage played a significant role.

Interested? Learn more about DEAI and medieval manuscripts and stay tuned for Part II: Other Voices (students, merchants, ranchers, pagans, travel, Jews, Arabs, Africans).

Sandra Hindman