What do you think of when you hear the expression “a sleeper”? Perhaps you think of adorable babies and toddlers safe and warm in their sleepers?

Or maybe your thoughts head in a more literary direction, and the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, pop into your mind:

Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, Passionary of Weissenau, MS Bodmer 127, f. 125v, c. 1170.

Did your thoughts stray to the movies? it is summer after all (even though most of us won’t be actually going to the movies as we did in summers past). Perhaps you thought of a “sleeper hit” like the “Blair Witch Project,” a small independent film made with a tiny budget of $60,000 in 1999, that caught the attention of audiences, and went on to make $248.6 million at the box office.

Or how about the “Rocky Horror Picture Show”? Ignored by audiences and critics alike when it was first released in 1975, it is now a much beloved classic, still attracting audiences more than forty years after its release.

What does all this have to do with medieval manuscripts? Here at Les Enluminures we have been thinking about “sleepers” on the Text Manuscript site–and decided that could mean many things. First, what are our “Blair Witch Projects” or “Rocky Horror Picture Shows”?

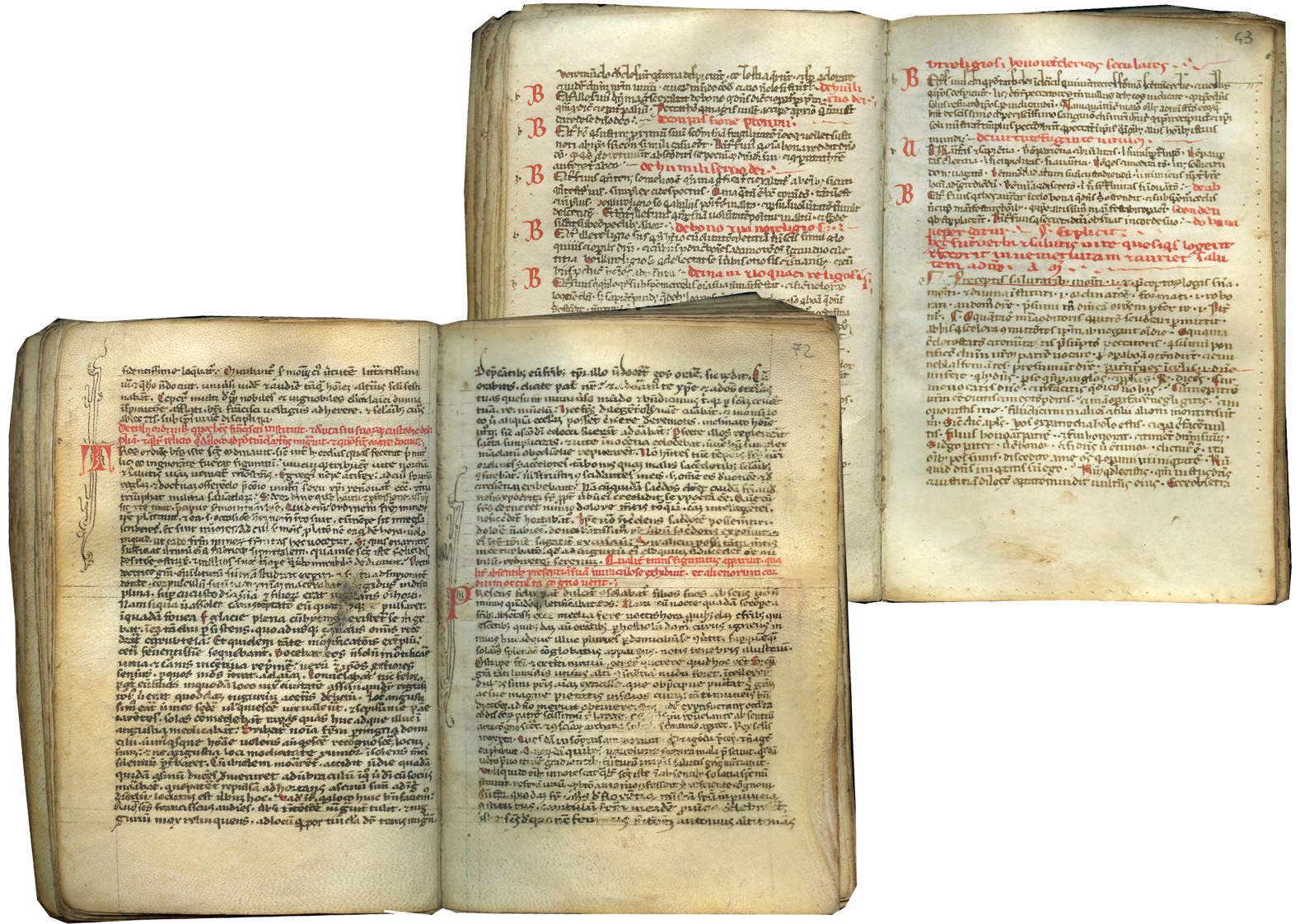

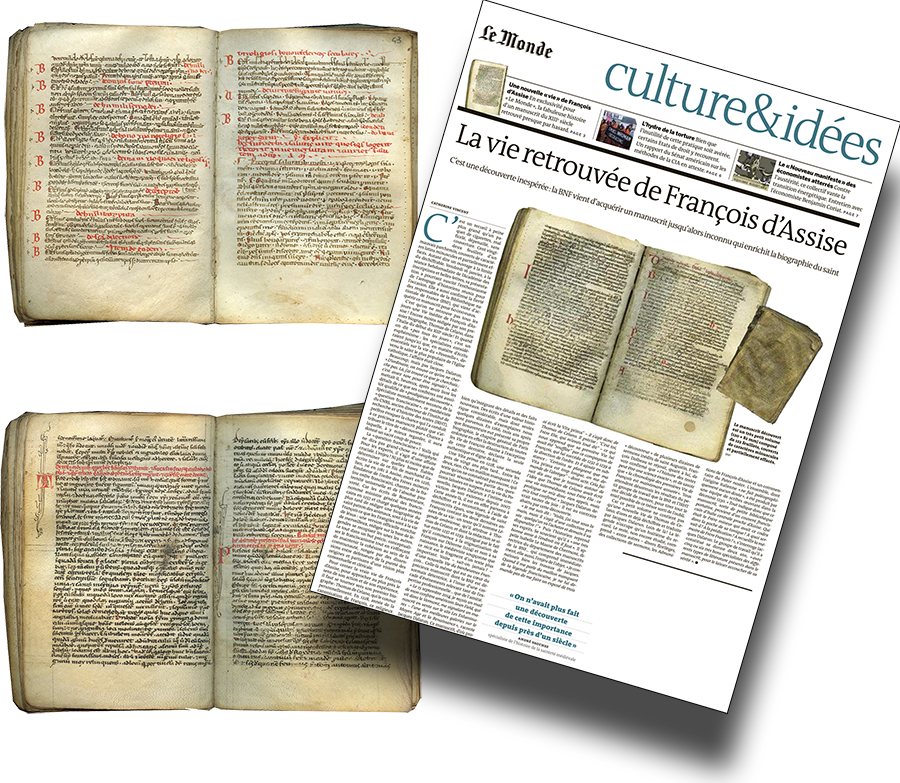

Les Enluminures, TM 686, Franciscan Miscellany, now BnF, MS , NAL 3245, ff.42v-43 and ff71v-72.

Perhaps the best example of a “sleeper hit” is one of the smallest, most unassuming little manuscripts we have ever sold. TM 686, now BnF, MS, NAL 3245, is a tiny Franciscan manuscript copied in Italy in the thirteenth century, no bigger than your palm, entirely lacking in decoration, and crammed full of texts. (We’ve mentioned it before in a previous blog post, “Milestone: One Thousand Text Manuscripts... And Many More To Come”.) When we described this manuscript, we were certainly very excited to discover that it included a new Life of St. Francis by Thomas of Celano! But we wouldn’t have predicted quite the splash this little manuscript would make.

The “Vie retrouvée” of St. Francis was greeted with astonishment by the scholarly community and beyond, attracting attention of the international press around the world. There was a story about it in Le Monde. Jacques Dalarun's edition of the Life of St. Francis appeared in 2015, and translations into French, English, Italian, German, Portuguese (and more) followed shortly after. The importance of the entire contents of this manuscript meanwhile has continued to emerge, and this tiny manuscript has now inspired more than sixty scholarly articles and books.

Andrea di Bonaiuto da Firenze, Triumph of St. Thomas Aquinas, with saints and angels, c.1366, Florence, Basilica of Santa Maria Novella.

Another example, one of my favorites, is TM 762, also a miscellany that was copied and used by either Franciscans or Dominican Friars. Like our Franciscan manuscript, this is not a very flashy manuscript; there is no decoration apart from a few red initials, and it includes numerous texts, copied by many different scribes. It is slightly larger than BnF nal 3245, but still quite small, and is German (or perhaps Austrian) rather than Italian. Its contents turned out to be quite significant. Certainly, notable among its numerous texts are 93 sermons by St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), and an additional c. 90 unidentified sermons. This manuscript was copied in the thirteenth century, quite likely while St. Thomas was still alive, and those ninety still-to-be identified sermons are quite tantalizing. It is still on our site; who knows what a splash it may make at some future date? A sleeper, just waiting for the right scholar to make it a hit.

Les Enluminures, TM 762, Sermons by Thomas Aquinas; Marian Exempla, and other texts, Southern Germany or Austria, c. 1250-1275.

When we think of “sleepers” on our text manuscript site, we also think of manuscripts that we love, but that have been on the site for a long time. The manuscripts that we occasionally revisit, asking ourselves, it is such a great manuscript, why do we still have it? (You might suggest that we are really thinking of “sleeping” inventory, any of which has the potential to become a “sleeper hit”).

N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, Portrait of Pompey the Great, c. 50 BC.

Take for example, TM 214, a manuscript of Plutarch’s Life of Pompey. Plutarch (c. 46-120 AD) was a Greek philosopher and author. His best-known work is a series of biographies of famous Greeks and Romans, arranged in pairs to illustrate their common virtues and vices. They are still interesting reading today; and you can easily find English translations. The Lives were almost totally unknown in the Latin West during the Middle Ages, but were rediscovered in the Italian Renaissance, and quickly became immensely popular in a number of Latin translations starting early in the fifteenth century.

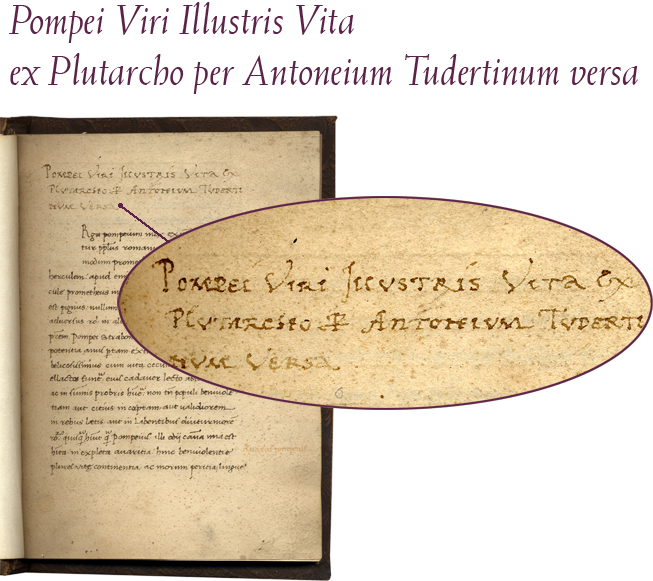

Les Enluminures, TM 214, Plutarch, Life of Pompey, in Latin translation, Northern Italy, c. 1470-1480, f. 1.

Our manuscript includes the life of Pompey the Great (106-48 B.C.), the distinguished military and political leader of the late Roman republic and Julius Caesar’s military rival. Plutarch originally paired the life of Pompey with that of the Greek hero, Agesilaus, the lame king of Sparta (444-360 B.C.), but in our manuscript there is no evidence that the life of Agesilaus was ever included.

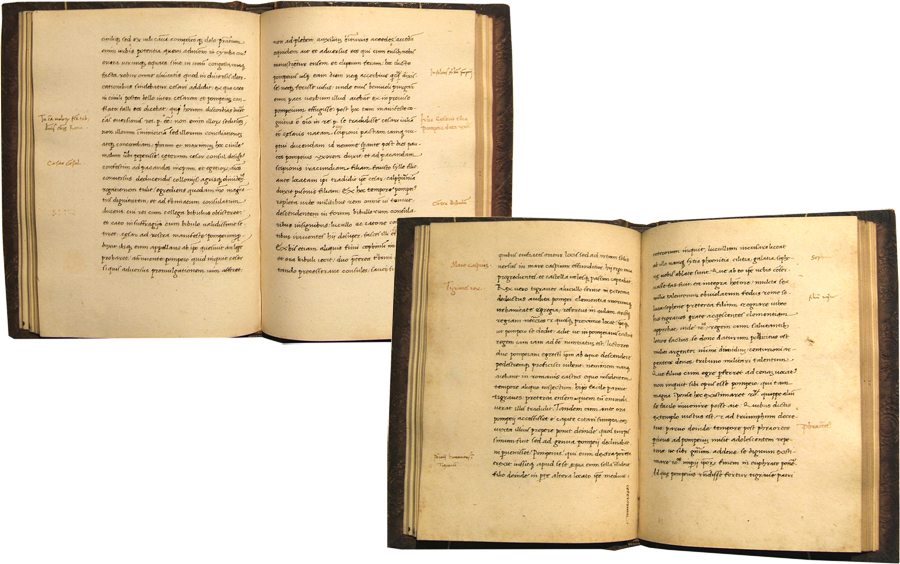

Les Enluminures, TM 214, Plutarch, Life of Pompey, in Latin translation, Northern Italy, c. 1470-1480, ff. 30v-31 and ff. 43v-44.

We don’t know who commissioned this manuscript; certainly it was someone for whom this life in particular had special interest (a fan of Plutarch? or a fan of Pompey’s?). The manuscript is on paper, but its lovely cursive humanistic script, relatively large size, and generous margins, all suggest that this was copied for someone of means (although, as is not uncommon in humanist manuscripts, the decorated initials were never completed and only blank spaces remain where they were meant to be).

Washington, D. C., National Gallery of Art, Master of the Osseranza (Sano di Pietro?), The meeting of St. Anthony and St. Paul, detail.

And why, we wonder, is this manuscript still with us? TM 87, also copied in Italy in the fifteenth century, includes three lives of early Christian monks and hermits by St. Jerome. This lovely little manuscript is a testimony to the importance of St. Jerome in Renaissance Italy, and to the popularity of the Desert Fathers. Many of you can probably think of frescoes or panel paintings from the fifteenth century celebrating their lives. And Jerome’s Life of St. Paul, the first hermit, surely has special resonance for everyone today, as we remember our lives in quarantine

Les Enluminures, TM 87, Jerome, Lives of Saint Paul, Malachus, and Hilarion, Northern Italy, c. 1400-1430.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!