If you are like me, you’ve probably visited WebMD more than a few times trying to figure out if your headache is just a headache or an early stage of brain cancer. Or, if you’re more old school, you may have one of those enormous home health compendiums sitting on a shelf somewhere in your house.

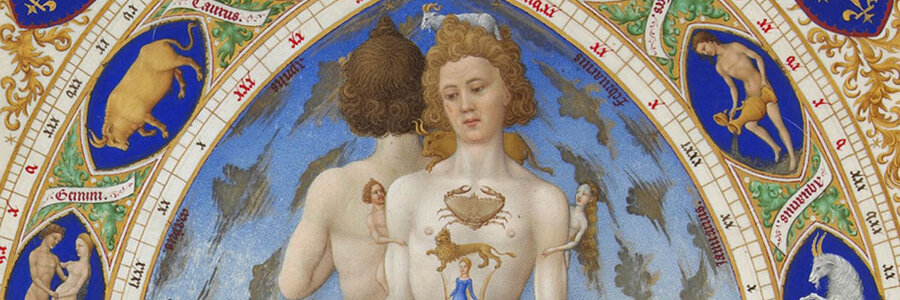

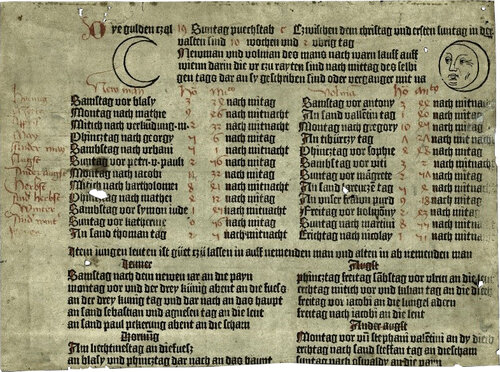

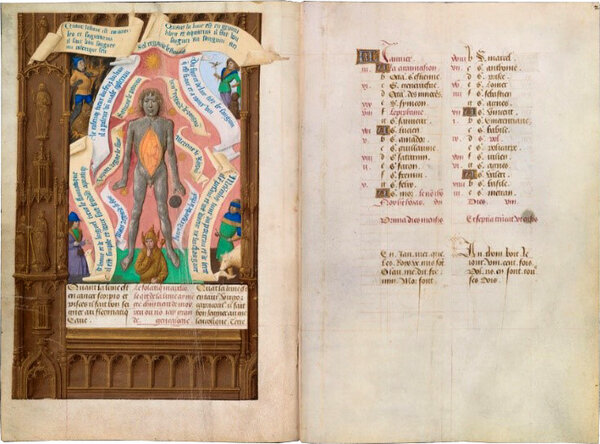

Home remedies have been popular for a long time as can be seen in this handy medical almanac from a Book of Hours published by Anthoine Verard August 22, 1506.

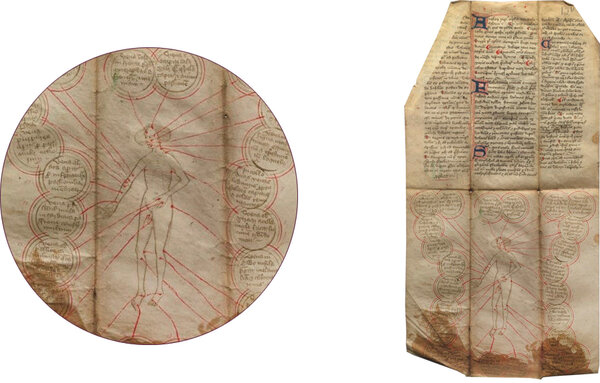

Les Enluminures, TM 1080, Printed Book of Hours, Paris, Anthoine Verard, August 22, 1506, ff.A1v-A2.

Of course, the therapy is practically unrecognizable to us, relying primarily on astronomical calculations and a theory that the body was composed of four distinct “humors” of blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. But while obsolete today, this medical calendar looked modern to early sixteenth-century readers, providing medical knowledge that had once only been available to professional doctors and surgeons.

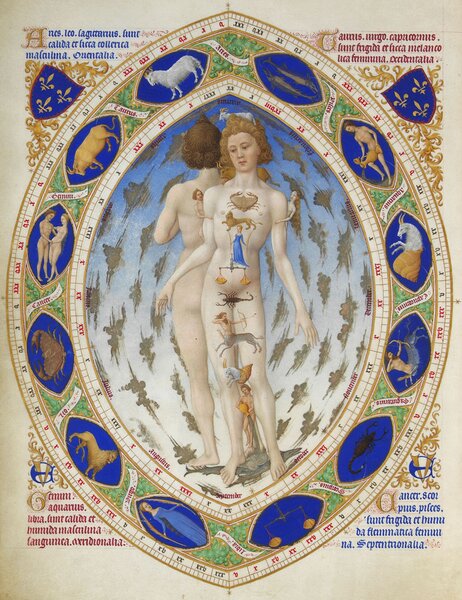

Medical almanacs and zodiacal figures began to appear in Books of Hours around 1490 but were unknown before this with the notable exception of the famous “zodiac man” from the Hours of Jean Duc de Berry painted by the Limbourg Brothers in 1412-1416.

Zodiac Man, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Limbourg Brothers, 1412-1416, Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 65, f. 14.

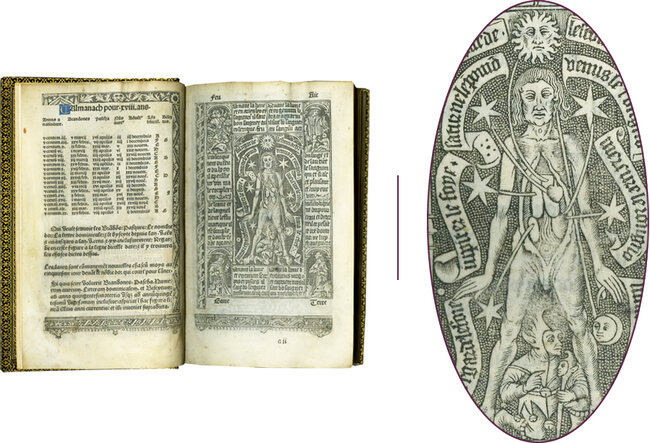

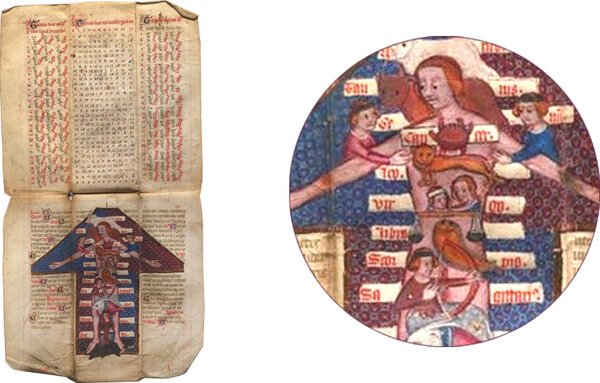

Until this point late in the fifteenth century, almanacs were owned primarily by medical professionals and painted on small folded sheets of parchment. Often referred to as a vade mecum (literally “take with me”) or “bat books” because they hung upside down from the physician’s belt, these charts were used to calculate the proper time for therapy. Since different parts of the body were believed to be controlled by specific astrological signs, it was important to ensure that the zodiac was in an auspicious alignment before opening a vein or cauterizing a boil.

Physician’s vade mecum with zodiacal and bloodletting figures, early fifteenth century, Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, MS acc. 12059.3.

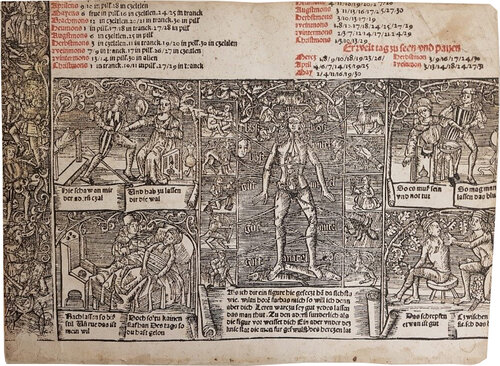

While the idea is rather amusing today, medical almanacs were essential to medieval practitioners. A royal ordinance of Louis XI in 1465, for instance, declared that every physician, surgeon, and barber must possess a current almanac or calendar to legally practice phlebotomy (bloodletting), and similar ordinances were issued in England and the Low Countries in the following decades. In 1457 the first printed almanac was published in Mainz by Johannes Gutenberg (predating the famous Bible). Soon after, “Aderlasskalendar” or bloodletting charts depicting an anatomical figure with zodiac signs became especially popular in Germany and were often displayed in physician’s shops as an emblem of the profession.

Aderlasskalendar, Vienna, Ulrich Han (?),1461-1462, Princeton, Scheide Library, no. 114.9.

Aderlasskalendar, Nuremberg(?), Kaspar Hochfeder, 1495. Montreal, Osler Library of the History of Medicine, folio WZ 230 C149 1495.

Since they provided essential information about one’s health, it wasn’t long before medical almanacs began to be collected by non-professionals. An especially popular version, the Kalendrier des Bergers (Shepherds’ Calendar), which claimed to reveal the “ancient wisdom” of the shepherds, was first printed by Verard in 1493 with numerous later editions, including a deluxe issue prepared specially for the French King Charles VIII. This Kalendrier was a rather eclectic publication, containing religious stories like the popular (and chilling) Vision of Lazarus as well as also a hefty dose of medical and calendrical information simplified for the novice.

Kalendrier des Bergers printed for Charles VIII by Anthoine Verard, 1493. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Réserve des livres rares, VELINS-518.

Given both the popularity and necessity of medical almanacs, it is easy to see why publishers like Verard began to reproduce them in Books of Hours as bonus material prefacing the calendar. By the mid-1490s, most Parisian publishers were printing Hours with medical almanacs, and even illuminators caught onto the trend, reproducing almanacs for their patrons like the famous Hours of Louis Quarré.

Hours of Louis Quarré, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 311, ff. 1v-2.

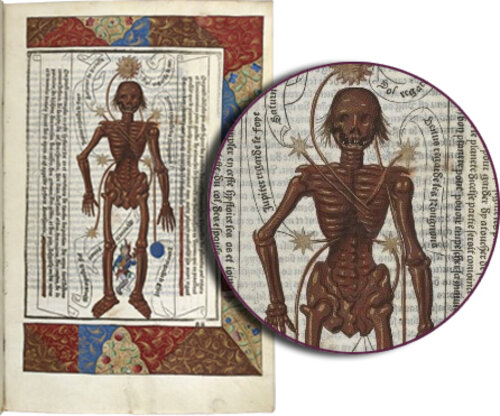

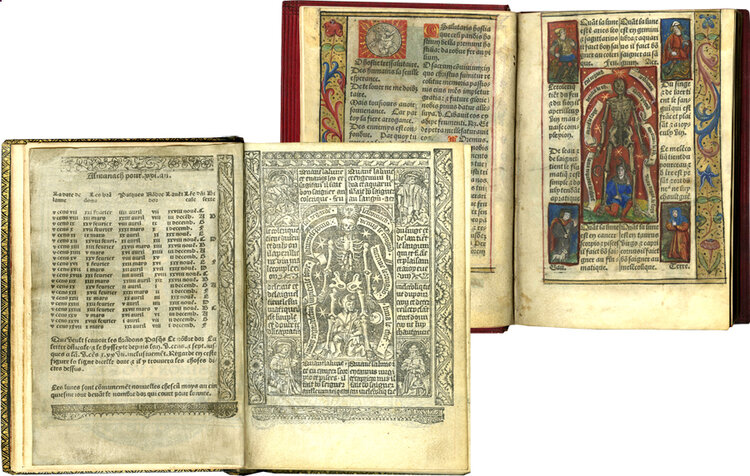

Later almanac varieties, such as our 1515 Hours by Simon Vostre and our 1526 Hours of Germain Hardouyn and his brother Gilles, swap the zodiac figure with that of a skeleton. The change likely had more spiritual than medical value, prompting the viewer to consider the mortality of the body and connecting the calendar with ensuing devotions found in the Office of the Dead.

Right, Les Enluminures, TM 1076, Printed Book of Hours, Paris, Germain Hardouyn, c. 1526, ffa1v-a2; left, Les Enluminures, TM 1078, Printed Book of Hours, Paris, Simon Vostre, c. 1515, ff.a1v-a2.

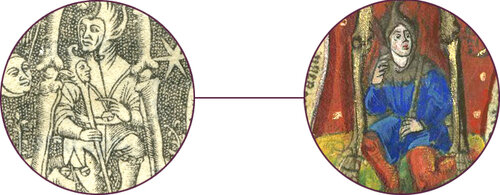

Note the fool who crouches between the skeleton’s legs—a curious detail. This was never a part of earlier almanacs but is found consistently in Parisian Hours as well as in the Kalendrier des Bergers. Fools were antiheros in late medieval society who playfully broke all the rules. The fool in our calendar may be connected to the “Feast of Fools,” a riotous party much like Mardi Gras that was especially popular in Paris and celebrated January 1.

Fools were also depicted in late medieval devotional works such as Psalters where they often accompany Psalm 14: “the fool says there is no God.” The fool perched between the legs of the skeleton/anatomical man in our Hours probably represents a similar subversion of the normal order of things, turning the world upside down, or in this context, inside out.

Psalter of Charles VIII, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 774, fol. 63v.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!