Medieval Books of Hours have many hidden stories to tell us, as we will find out in the following tales of three books and three women: Françoise, Marguerite and Catherine.

Confined as we are to our homes during the Covid-19 crisis, you might say that this is not the appropriate moment to be reminded of the haunting fate that befell the first mistress of King Francis I of France, Françoise de Foix. According to several historians, she finished her days imprisoned at home by her jealous husband, Jean de Laval, who eventually killed her. Nevertheless, I should add that we have no way of knowing for certain if these gory events are true. The recent discovery of an acrostic poem, quite likely by Françoise herself, appears to shed new light on her destiny.

Besides the feeling of being imprisoned in our homes, for many people the current confinement accentuates what matters most in life: love, laughter, music, dancing, running... This brings me to another poem composed in late medieval France, entitled “Plaisir fait vivre”. What are the pleasures that make life worth living for each of us?

Finally, a third book of hours evokes a man with a good many years behind him, apparently reflecting on his life and past choices with some regret. As Books of Hours are collections of texts for private devotion and emotional refuge, they occasionally reveal, as these examples show, particularly poignant moments in a person’s life. Many say that we are now at a turning point: the major health crisis we are living through will mark, if we survive it, our lives with before and after.

-

Françoise de Foix, Comtesse de Châteaubriant (c. 1495-1537)

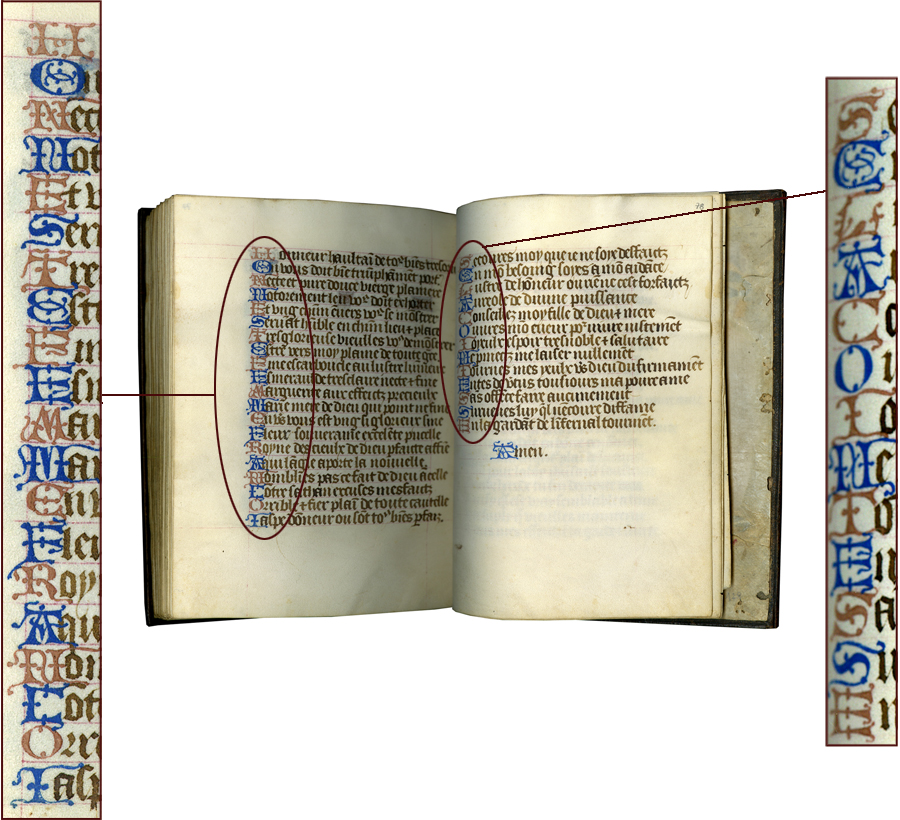

Back in December, I was cataloguing a French book of hours, BOH 179, which at first glance resembled dozens, maybe hundreds of similar books that I had seen before, painted in the 1480s for an unidentified woman (or a couple) in Normandy, this one in Bayeux. However, what caught my attention was a rhymed prayer copied at the end of the book for a later owner. The prayer is built around an acrostic: the initials beginning each verse spell out “Honneste femme Françoise La Cointesse (Comtesse)”, i.e. Honest woman/wife Françoise The Countess. Hitherto unknown, the prayer was very likely composed by Françoise de Foix, the Countess of Châteaubriant, and the first mistress of Francis I, King of France.

Les Enluminures, BOH 179, The Hours of Françoise de Foix, added prayer, ff. 77v-78, c. 1531

Honneur haultain, de tous biens tresoriere,

On vous doit bien triumphaument porter ;

Necte et pure, douce vierge planiere

Noto(i)rement l’en vous doit exhorter

Et ung chacun envers se monstrer

Servant, humble, en chacun lieu et place.

Tres glorieuse, vieullés vous demonstrer

Estre vers moy plaine de toute grace.

Fine escarboucle au lustre lumineux

Esmeraulde tres claire necte et fine,

Marguerite aux effeictz precieulx,

Marie mere de dieu qui point ne fine

Envers vous est ung si glorieux sine,

Fleur souveraine excelente pucelle,

Royne des cieulx de dieu parfaicte affine

A qui l’angle aporte la nouvelle

N’ombliés (N’oubliez) pas ce fait de dieu ancelle :

Contre sathan excusés mes faictz

Orrible et fier, plain de toute cautelle.

Jaspe d’onneur ou sont tous biens parfaiz

Secourés moy que je ne soye deffaictz

En mon besoing soyés a mon aidance

Lustre de honneur ou rien ne c’est forfaictz

Aureole de divine puissance

Conseillez moy fille de dieu et mere

Ouvrés mon cueur pour vivre justement

Joyeux espoir tres noble et salutaire

Ne permectz me laiser nullement.

Tournés mes yeux vers Dieu du firmament

Entés de vertus tousjours ma povre ame

Sans offence faire aucunement

Survenés luy qu’il n’encoure diffame

En la gardant de l’infernal tourment.

It is a heart-rending supplication to the Virgin Mary by a woman accused of great offences, who pleads for help and proclaims her innocence, honneste femme. It would have been written by Françoise during her imprisonment.

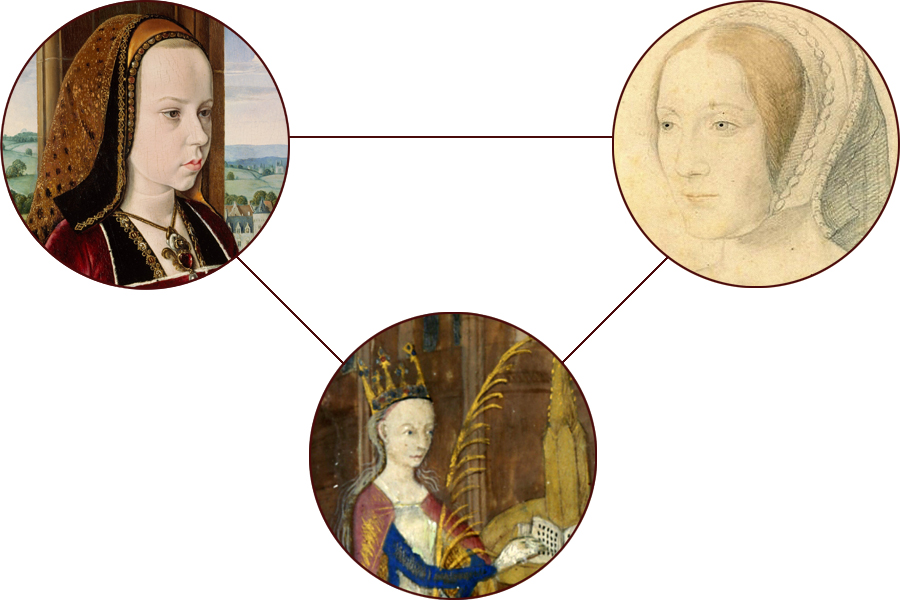

Françoise de Foix, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

The young Madame Châteaubriant was admired for her remarkable beauty and grace, which enticed King Francis I to summon her to court along with her husband, Jean de Laval-Châteaubriant. She was very intelligent and cultured. She knew Latin and Italian, and wrote poetry, which attracted the learned king. Françoise became the first official mistress of the king in 1518; she was 23, he 24. She remained his mistress until 1528. In 1525, the king was imprisoned in Pavia, and suddenly Françoise was no longer protected from the hatred of the king’s mother, Louise of Savoy. She was obliged to leave the court and return to Châteaubriant. Louise, who detested the de Foix family, had never liked Françoise. As a strategy for getting rid of her, the queen mother introduced a new mistress to the king on his return from captivity in 1526: Anne de Pisseleu. For two years Françoise and Anne competed for the king’s favor, after which Françoise accepted her defeat and returned to Châteaubriant. Although the king continued to love her, once she had left the court, he could not protect her against the revenge of her husband. According to accounts by various historians, Jean de Laval imprisoned Françoise and their thirteen-year-old daughter, Anne, in a completely dark room, its walls covered with black tapestries. The child died within six months, and Françoise in 1537. Françoise probably wrote the prayer when her daughter was still alive, around 1531. This date corresponds to the style of the humanistic initials in gold and blue that begin each verse.

Françoise saw her former lover for the last time during the king’s stay in Brittany in 1532. The epitaph on her tomb was written by the king’s official poet, Clément Marot:

Soubz ce Tombeau gist Francoyse de Foix,

De qui tout bien tout chascun soulait dire,

Et le disant, oncq une seule voix

Ne s’avanca d’y vouloir contredire.

De grand Beausté, de Grace qui attire,

De bon Scavoir, d’Intelligence prompte,

De Biens, d’Honneurs, et mieulx que ne racompte,

Dieu Eternel richement l’éstoffa.

O Viateur, pour t’abréger le Compte,

Cy gist ung rien, là où tout triumpha

Although it was widely suspected that Jean de Laval was responsible for Françoise’s death, he was not officially accused. The king ordered the death to be investigated by his friend, Anne de Montmorency, Marshal of France. However, the investigation was probably biased from the start, because Anne de Montmorency was the brother of the second wife of Jean’s father, François de Laval. Consequently, Jean de Laval, who had no descendants, gave the barony of Châteaubriant to Anne de Montmorency, and the investigation of Françoise’s death stopped there.

-

Marguerite of Austria (1480-1530)

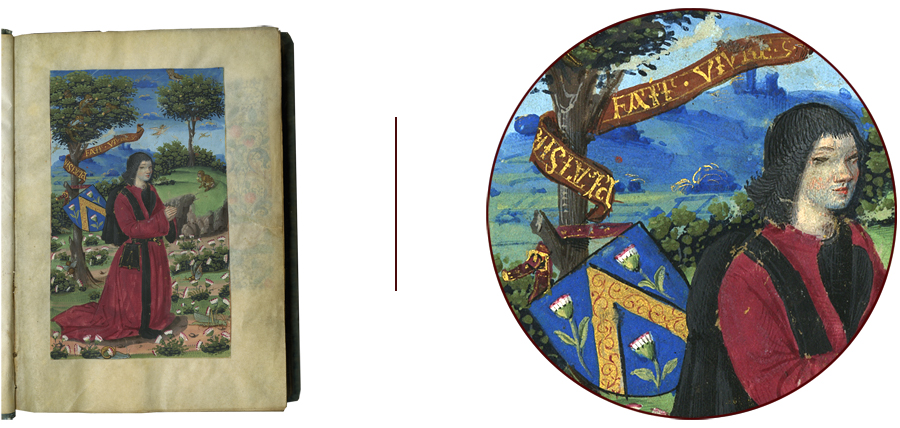

In January, while studying another book of hours painted in Rouen in the 1480s for an unidentified woman, BOH 183, I was captivated by a miniature added to the book. The miniature shows a young man kneeling in prayer, with his coat of arms, d’azur au chevron d’or accompagné de trois marguerites au naturel, and his motto “Plaisir fait vivre” attached to the tree behind him.

Les Enluminures, BOH 183, a miniature on a single leaf added to the beginning of the book, c. 1490-1495.

In the miniature, marguerites (daisies) fill the field in small bouquets and decorate the coat of arms, as if they were the personal emblem of the man portrayed. However, one curious detail suggests that it is not an ordinary patron portrait: the man’s eyes are closed. Daisies, marguerites, symbolize love; they appear in springtime, the season of love. Is this a poetic, figural portrayal of love toward a woman called Marguerite? In the miniature there are also monkeys perched in the tree and sitting on the grass, eating golden fruits referring to pleasure, the young man’s desire for his beloved. Some forty years after the image was painted, around 1527-1529, Marguerite of Navarre, the sister of Francis I, would describe love in these terms in her poem Le miroir de l’âme pécheresse:

Me vient fermer une branche les yeux.

Tombe en ma bouche, alors que veux parler

Le fruit par trop amer à avaler.

Two poems entitled “Plaisir fait vivre”, composed c. 1480-1482 and c. 1491-1494, around the time our leaf was painted, are essential for understanding the miniature. The earlier poem was written by the jurist Jean d’Affray, and reads as follows:

Plaisir Fait Vivre

La Marguerite est une Fleur

Qui contient toute couleur

C’est la doulceur qui tout consomme

Pour restouyr l’espoir de l’home

The poem precedes a treatise by d’Affray justifying the rights of Mary of Burgundy to the duchy of Burgundy, inherited from her father, the duke Charles the Bold (Lille, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 551, f. 15). Louis XI contested Mary’s inheritance because she was not a male heir, and intended to annex Burgundy to the territory of the French crown. D’Affray’s text is undated, but must have been composed between 1477, the death of Charles the Bold, and 1482, Mary’s own death. It can be dated even more precisely, after January 10, 1480, the date of birth of Mary’s daughter, Marguerite of Austria, because the Marguerite in the poem undoubtedly refers to her. (In 1519, another jurist, Jean Beaufils, would use d’Affray’s poem in the dedication of his French translation of Liber de vita Christi ac omnium pontificum to Marguerite of Angoulême (later Queen of Navarre), the sister of Francis I.)

On March 27, 1482 Mary of Burgundy died accidentally after falling from a horse. In order to avoid war between France and the Flemish states, Louis XI negotiated the betrothal of his son, the Dauphin Charles (the future Charles VIII) and Mary’s daughter, Marguerite of Austria. It was the most important union for France at the time, sealing the Treaty of Arras, signed on December 23, 1482.

In January 1483 a Flemish delegation was sent to France to ratify the peace treaty and the betrothal of the Habsburg princess with the French dauphin. When the Flemish party arrived at the royal court in Amboise and met the dauphin, the abbot of Saint-Bertin, who was part of the delegation, handed over to Prince Charles a letter from Marguerite’s father, Maximilian of Austria, and offered a garland made of five marguerites. The official engagement ceremony, which took place in Amboise on June 22 of the same year, is known in detail from the descriptions of the event made by the Flemish ambassadors. When the ceremony began, the dauphin Charles entered wearing a crimson-colored satin robe lined in black. Notably, the robe worn by the man in our miniature resembles this description.

Jean Hey, Marguerite of Austria, c. 1490, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Although at the time of the engagement, Marguerite was only three and half years old, and Charles thirteen, she lived at the French court as the betrothed queen of Charles VIII for eight years, and the couple developed genuine affection for one another. In the end, however, they were not allowed to live together happily-ever-after. In late 1491 Charles was obliged, for political reasons, to repudiate Marguerite in order to marry Anne of Brittany.

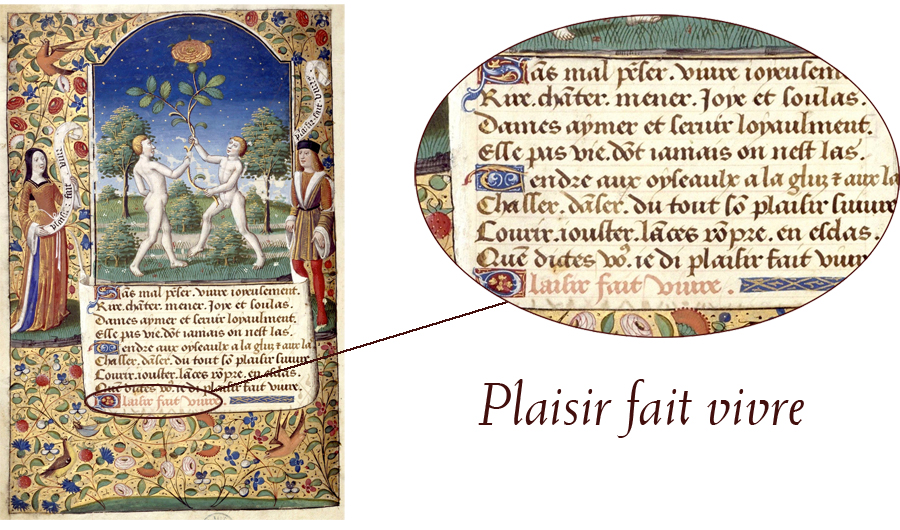

In the context of this unexpected misfortune that befell Marguerite, it seems incongruous that the second contemporary poem to include the refrain “Plaisir fait vivre” would be one composed in honor of Charles VIII’s union with Anne of Brittany. It is a poem about life and death, found in a manuscript book of hours prepared by the Parisian publisher Antoine Vérard around 1491-1494 for Charles VIII (Madrid, Biblioteca nacional, MS Vitr. 24-1, ff. 110v-111). Vérard apparently composed the poem personally for the king, and it only survives in this manuscript. It reads:

Sans mal penser vivre joyeusement,

Rire, chanter, mener joye et soulas,

Dames aymer et servir loyaulment,

Esse pas vie dont jamais on n’est las ?

Tendre aux oyseaulx à la gluz et aux lacis,

Chasser, danser, du tout son plaisir suivre,

Courir, jouster, lances rompre en esclas,

Qu’en dictes vous ? je di(s) plaisir fait vivre,

Plaisir fait vivre.

Madrid, Biblioteca nacional, MS. Vitr. 24-1, f. 110v, c. 1491-1494.

The poem continues for eight verses which remind us that life - for everyone - ends in death. This gives further emphasis to the injunction in the first eight verses to live joyfully: laughing, singing, loving, hunting, dancing, running, jousting, and pursuing pleasure. These lines on the enjoyment of life are flanked by a couple representing Charles and Anne holding banderols containing the phrase “Plaisir fait vivre”. The miniature above the text, depicting two nude boys holding a rose, the attribute of Venus, express a promise of love and children for the young king and queen.

The added miniature in our book of hours includes a banderol with the same counsel “Plaisir fait vivre”. The flowers are not roses, but marguerites. The image is datable by costume and style to approximately the same period, the early 1490s. Does our miniature refer to Charles’s first intended queen, Marguerite of Austria? It is not known when the miniature was inserted in the Rouen book, whether it was intended for the same person as the book, or whether the miniature was bound in the book much later. But it is not impossible that the book was owned by Marguerite of Austria. During her life she would amass a library of nearly 400 volumes, most of which were manuscripts that she acquired “second hand”, books that were not initially made for her, but were given to her. Notably, when she was just a little girl, she already owned manuscripts. If the book was not hers, it might have belonged to someone close to her in court, perhaps one of her ladies-in-waiting, whose names she transcribed at the end of her copy of a Bible moralisée when she was at the French court (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Fr. 9561, f. 192).

In the miniature, the kneeling man has his eyes closed and his hands in prayer. His expression, the marguerites, and the monkeys evoke a man dreaming of a woman, Marguerite, with hidden desire, and perhaps nostalgia and regret. Could the miniature be a parting gift from Charles to Marguerite, after their engagement was annulled in the autumn of 1491? The way the banderol encircles the tree, with the word “Plaisir” represented upside down, overturned, can be interpreted to signify Charles’s obligation to repudiate the pleasure of love he had shared with Marguerite. Marguerite was deeply hurt by Charles’s action, but Charles also was reluctant to abandon her: she would stay two more years in France before being returned to her father. One final, important detail in the image appears to express Charles's feelings. The chevron on the shield has symbolic value in the science of heraldry: it signifies constancy, loyalty and protection. Is this image Charles’s farewell token to Marguerite symbolizing the promise “I will never forget you”?

- Catherine

A third French book of hours, painted around 1465 probably in Angers, BOH 187, completes our peregrination through the byways of unhappy love stories. In this book I was intrigued by a series of enigmatic pictorial details, which suggest that the manuscript was made for a man with a broken heart.

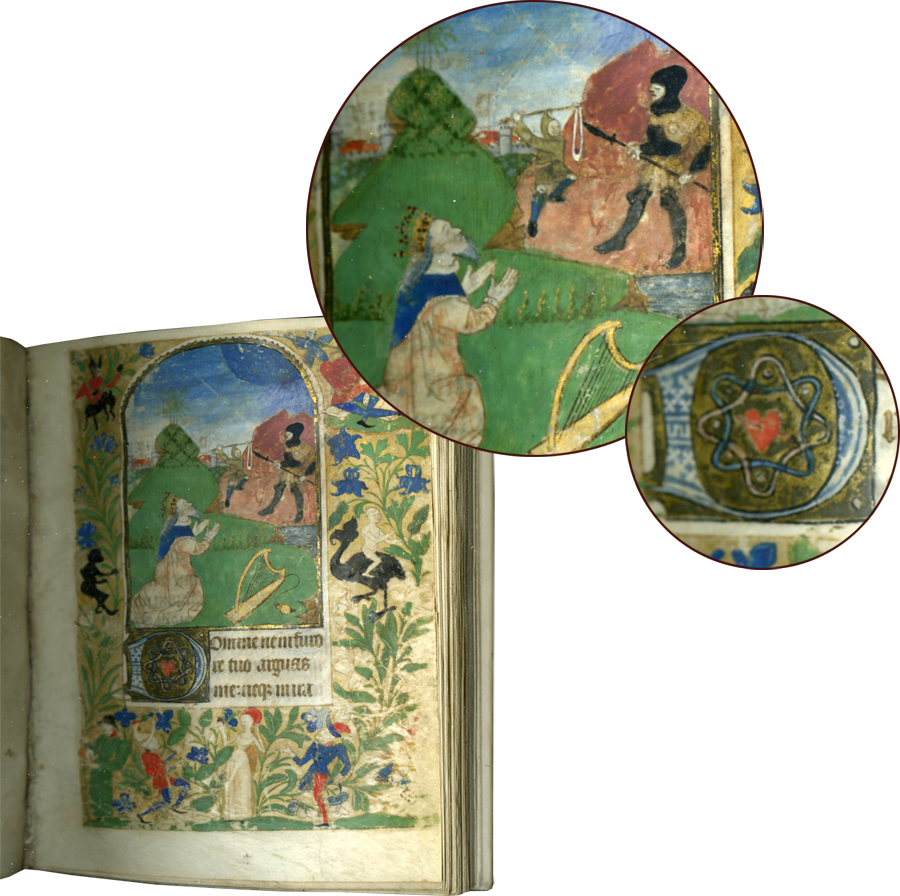

Les Enluminures, BOH 187, David in prayer, f. 47, c. 1465

The initial on the leaf that opens the Penitential Psalms contains a pierced heart inside two entwined bands forming a love knot.

In the margin below there are two noblemen dancing around a lady, and one of the men wears a hat crowned with a cockerel, signifying that he is a coquart or cuckold. The musician plays a three-holed pipe called galoupet and a tambourin; the poet François Villon (1431- after 1463) refers to these instruments as implying that someone is playing around.

Another scene on this page shows a couple shuffling cards, and Villon in his poetry associated this with the act of scorning, whereas cardplaying in general signifies vice.

Below the couple, a nude figure rides backwards on a black bird, signifying vilification, and extends his hand to pick an ancolie, which represents melancholy.

In the inner margin, there is a grotesque, half man and half donkey, with the black ears of a jackass, who admires himself in a black mirror. Below, there is a black monkey. Black in these images signifies bad, white good.

The original owner was most likely a man, full of regrets. The Psalm begins plaintively, “Out of the depths I cry to thee O Lord! Lord, hear my voice!” He was courting a woman around whom many danced, but he suffered from several vile faults: vanity, scorn, sexual appetite. The woman who rejected his affections (or whom he arrogantly rejected, and now longs for) may have been named Catherine, a woman for whom he will pine forever, as suggested by the graying hair of the saint in the miniature of St. Catherine. This would be a reverse take on Villon’s famous poem Les regrets de la belle Heaulmière.

Les Enluminures, BOH 187, St. Catherine, f. 120.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!