The margin is “in” nowadays not “out.” Our recent exhibition at Les Enluminures (The Margins of Medieval Art: Questioning the Center) got me thinking about the margins in other types of manuscripts, text manuscripts that are not especially illuminated. We have come to accept that artists used the margin creatively, often glossing, parodying, modernizing, and problematizing the texts authority, to paraphrase Michael Camille (Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art, 1992). What about authors? What do they have to say about margins? What about readers? What about scribes? How did they use them?

With the help of my informed colleague Laura Light, we put together a few comments that give a sense of how medieval authors thought about the margins of manuscripts. Writers were sensitive to the procedures of copying texts. The Dominican friar and one of the great encyclopedists of the Middle Ages Vincent of Beauvais (d. c. 1264) told readers that he “added [the names of authors] among the lines themselves, just as Gratian did in his compilation of canons, and haven't inserted them in the margins ... lest they easily be transferred into the wrong place."

Miniature of Vincent of Beauvais in a manuscript of the Speculum Historiale, translated into French by Jean de Vignay, Bruges, c. 1478-1480, British Library Royal 14 E. i, vol. 1, f. 3 (detail)

Thomas Becket’s biographer, Herbert Bosham (active 1162-1169), notes that he put the names of the authors quoted in the margins, so that readers could identify whose words they were reading. These examples tell us that writers distinguished the margin from the main text block, paying attention both to the habits of scribes and the needs of readers.

St Thomas and his Secretary Herbert of Bosham. Illustration from A Short History of the English People by JR Green (Macmillan, 1892).

Let us remember that the margins of medieval manuscripts were ample – Erik Kwakkel has emphasized that the average space around a writing block was about 50%. As he puts it, the manuscript page was “half empty, half full.” This left a lot of blank space for readers to interact with their books. One common annotation by readers is the manicula, literally “little hand” in Latin. A great variety of pointing hands can be found in manuscripts. They sometimes wear gloves, have fancy cuffs, even show the whole sleeve of a garment, don rings on their fingers. They are almost always distinguished by an index finger (usually) that points to a specific line of text. The equivalent of a modern highlighter, or perhaps a pen-drawn arrow, the flourished pointing hand is a source of endless amusement, but it also reveals what different readers found interesting in their books.

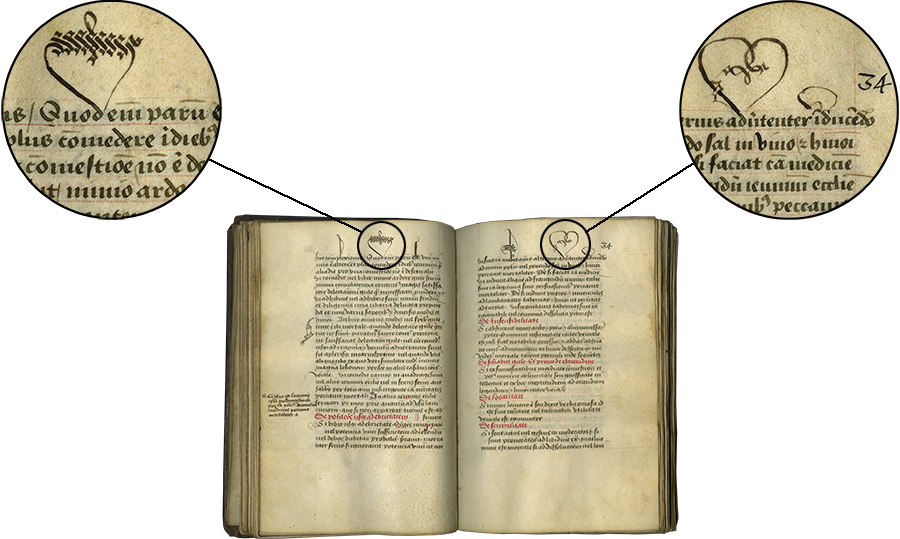

Whereas readers typically used the vertical blank space of the margin, scribes often turned to good use the top and bottom horizontal margins. Some especially adept scribes employed “cadels,” which are calligraphic ascenders that stretch the vertical bars of the letters into the empty space above the written line, often forming decorative patterns. The word “cadel” derives from the Latin capitalis which also produced the French word cadeau meaning gift and chattel meaning tangible property. I like the idea of the “cadel” as a scribe’s gift to the page, as part of his own personal property. Some of my favorite “cadels” enliven the pages of a medieval confessor’s manual, ironically strewing the upper margins with calligraphic hearts.

Les Enluminures, TM 771, ANONYMOUS, confessional manual; ANTONINUS FLORENTIUS (ANTONINO PIEROZZI), Confessionale, Book II, Northern France, c. 1450-1500 ff.33v-34

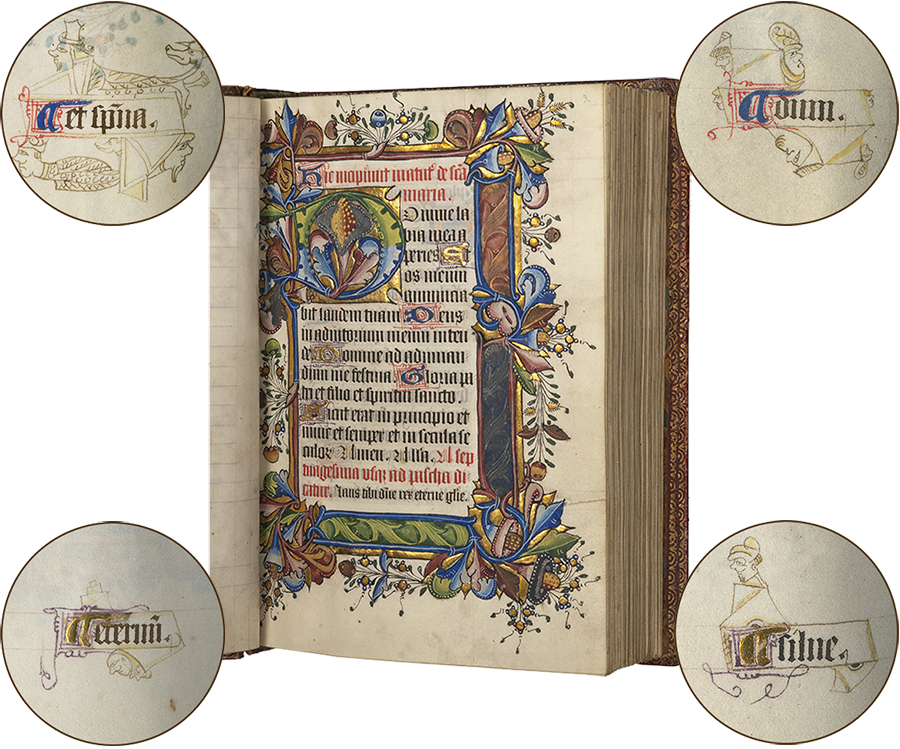

Other scribes imagined possibilities for animating catchwords, that is, the words written at the end of each gathering at the bottom of the page, which rehearse the opening words at the beginning of the next page that open the succeeding gathering. In the simplest examples, flourishes of penwork frame the word or words. Sometimes the bodies of animals – dogs and marmots – became receptables for the words. More intricate examples, such as occur in the Spicer Hours made for a spice merchant in London the mid-fifteenth century, include fanciful drawings of animals, grotesques, heads, and banderoles.

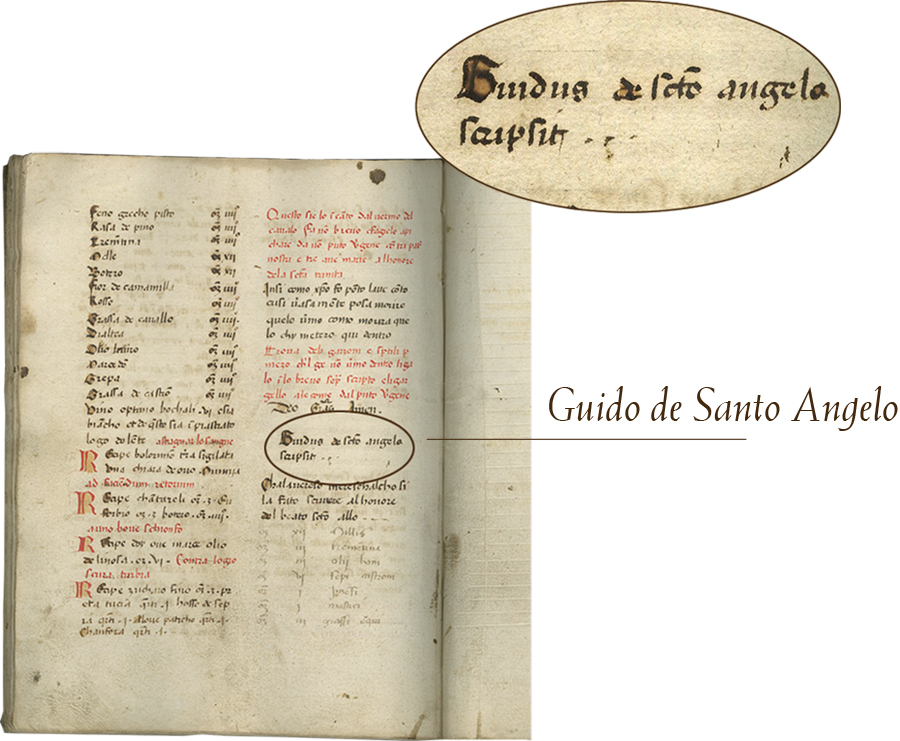

An unusual marginal intervention by a scribe occurs in manuscript called the “Book of the Health of Horses” by Laurentius Rusius, in its Italian translation, written most probably for the ducal farrier at the court of Duke Niccolo III d’Este. The manuscript treats the diseases of the horse and how to cure them, the eyes, mouth, hoofs, back, and the influences of the moon on equine maladies. The scribe signed his name in a colophon “Guido de Santo Angelo,” where he also expressed his devotion to the patron saint of horses, St. Eligius.

Les Enluminures, TM 1026, LAURENTIUS RUSIUS, Hippiatria sive Marescalia (Book on the Health of Horses), Northern Italy (perhaps Ferrara), dated 1434, f.69v

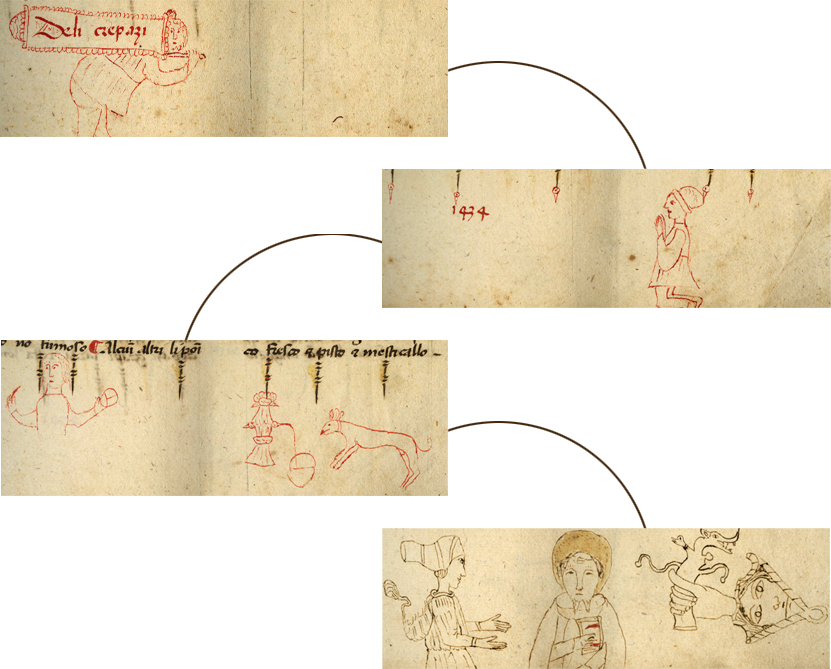

In one of the lower margins, he added a pen-drawn doodle of St. Eligius between a maid servant and a dragon. His other doodles portray life on the ducal estate and stables – a peasant carrying a load on his back, a dog drinking from a fountain while his mater looks on. A drawing of a man in prayer (likely the donor) and a date, 1434, probably depicts the patron and reveals the date of copying the manuscript.

Les Enluminures, TM 1026, LAURENTIUS RUSIUS, Hippiatria sive Marescalia (Book on the Health of Horses), Northern Italy (perhaps Ferrara), dated 1434, details

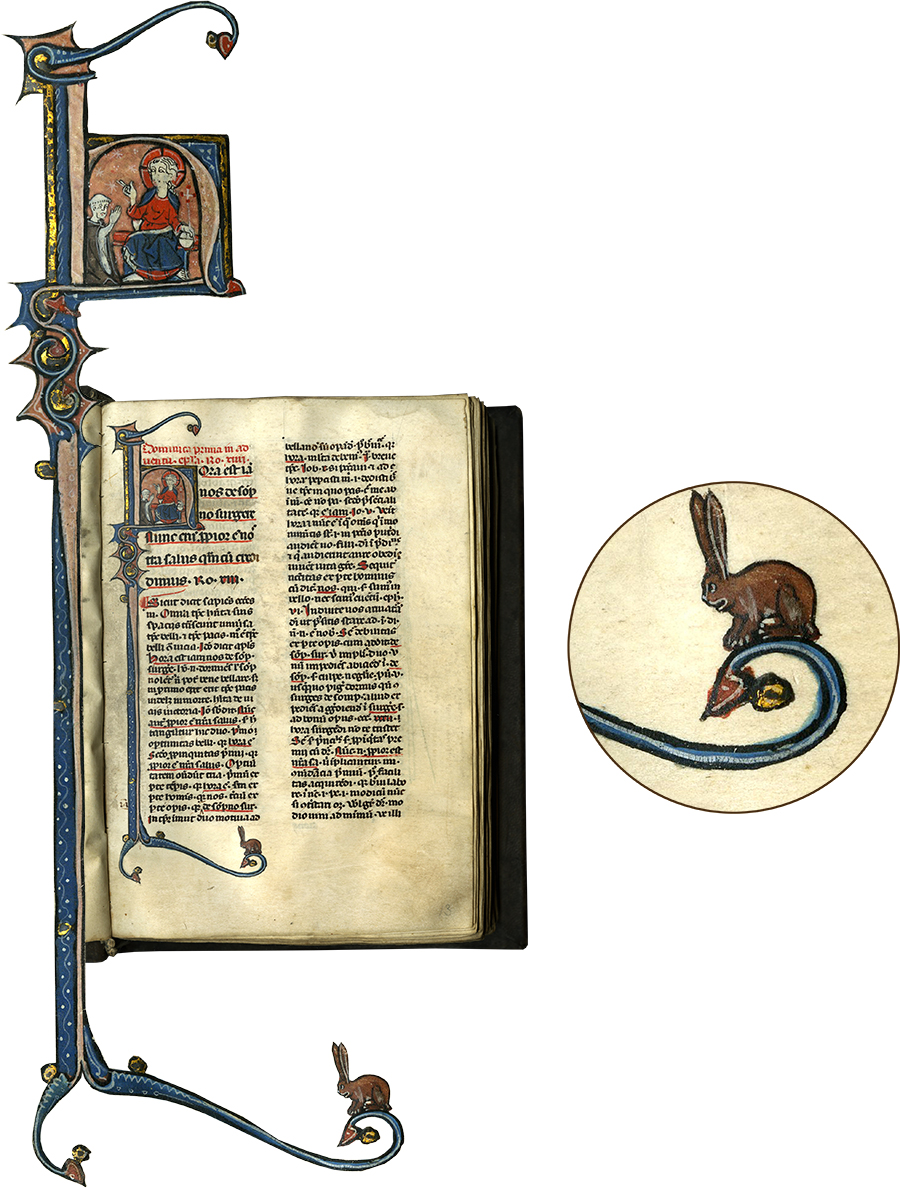

Sometimes the same artists that illuminated deluxe manuscripts such as Books of Hours, Breviaries, Psalters, and Bibles, did double duty and added painted marginalia to accompany text manuscripts. This is the case with a thirteenth-century Parisian copy of Sermons by Nicolas of Gorran, a Dominican preacher and royal advisor. Produced in a high-end Parisian workshop, the manuscript opens with a historiated initial of Christ enthroned who blesses the preacher-author kneeling before him. Of interest to us here is the baguette border along the left margin that terminates at the bottom of the page with a rabbit posed precariously on the tip of the branch. Rabbits are ubiquitous in the margins of medieval manuscripts. They hunt, they ride horses, they wield swords, they attend church, they play music

Les Enluminures, TM 868, NICHOLAS OF GORRAN, Sermones de Tempore et de Quadragesima [Sermons for the Temporale and for Lent], sermons excerpted from the Sermones de Sanctis [Sermons for the Feasts of Saints], Northern France, Paris?, c. 1275-1300, ff.12v-13

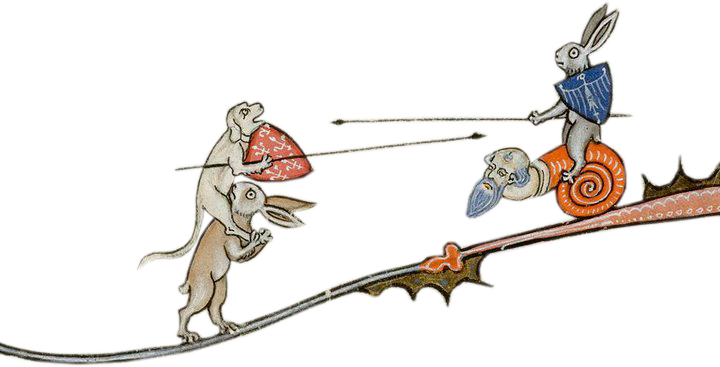

The conventions of medieval symbolism dictate that they are harmless god-fearing creatures, symbolic of innocence and purity and that only in the topsy turvy “world upside down” do they turn into fierce and violent predators. What is the solitary rabbit doing here? Is it the god-fearing creature listening attentively to Nicolas’s sermons? Or can we take it at face-value: as a cute fuzzy bunny with long floppy ears that brings a smile to our face, much the way that a stuffed animal nestled in an easy chair does to children and adults alike?

Details from left to right: TM 868, NICHOLAS OF GORRAN, ff.12v-13; The Thourotte Hours, ff. 32v-33; The Arenberg Psalter-Breviary, ff.239v-240; The Roman de la Rose, f.1

Alive and teeming with activity are the margins in many text manuscripts. Next time you open a medieval manuscript just take a look.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!