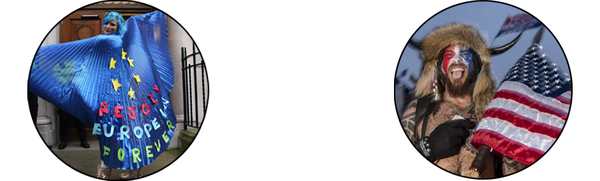

Nationalism vs. European unification; these have been pressing questions in Europe since the end of World War II, if not before. They are crucial questions now (and highly controversial ones), given the resurgence of nationalist movements across the world, whether one is contemplating Trump’s “America first,” Brexit, or Marine Le Pen. And these issues certainly have ramifications for medieval historians since contemporary political movements are looking back to the Middle Ages (or a fictionalized version of the medieval past) to support their agendas.

A big and very important topic. But we are manuscript scholars at Les Enluminures, and today in this blog, I want to explore just one tiny part of it (for those interested in exploring the broader issues, there is a brief list of readings at the end). What does the manuscript evidence tell us? In particular, what is the evidence of trans-national participation in the book trades? How often did artisans from different parts of Europe work together to make a manuscript?

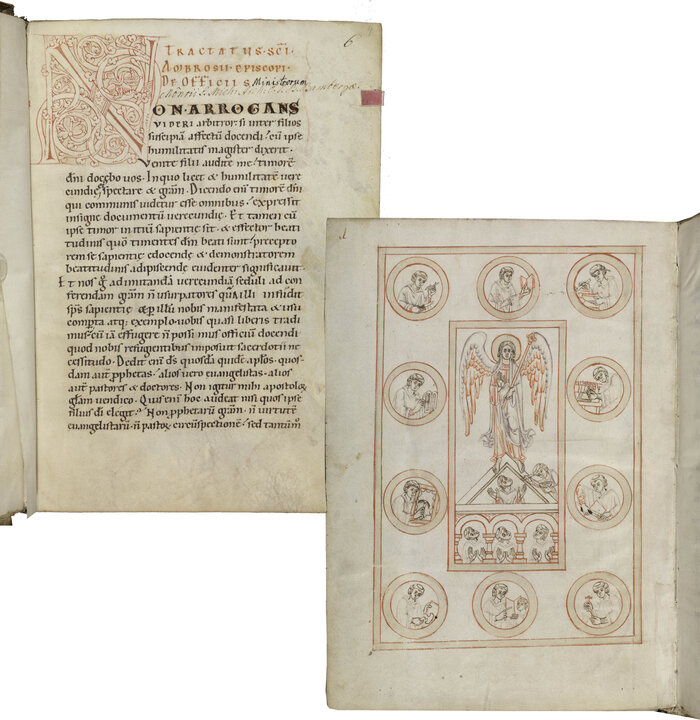

The answer certainly depends on when we are talking about. Early in the Middle Ages, most manuscripts were made in-house in a monastic scriptorium by the monks or nuns themselves.

Bamberg, Kloster Michelsberg, Ambrose, Works, middle of the twelfth century, Staatsbibliothek Bamberg Msc.Patr.5, The monastic scriptorium.

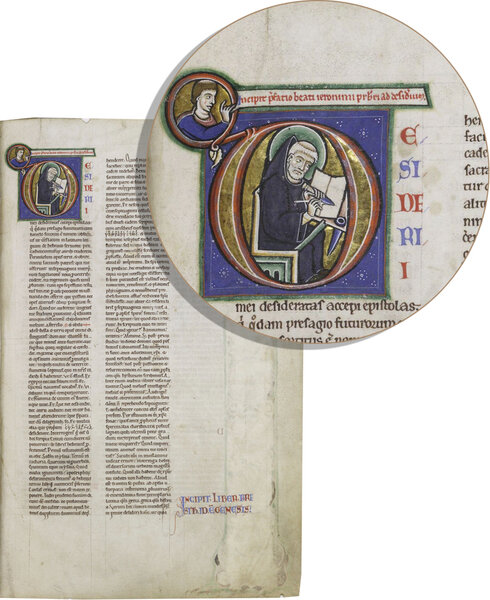

By the twelfth century, however, there is evidence of artists, laymen rather than monks, who travelled to various monasteries, where they were paid for their labors. Two examples are the artists known as the Master of the Morgan Leaf, who worked on the monumental Winchester Bible and on the wall paintings of the chapter house at Santa María de Sigena in Northern Spain (Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya), and the Simon master, who painted manuscripts at St. Albans Abbey in England as well as numerous manuscripts in various locations in France.

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 48, Bible, c. 1180, Genesis initial by the Simon master.

New York, Morgan Library, MS M.619 verso, single leaf from the Winchester Bible, England, Winchester, between 1160 and 1180: image, painted by the Master of the Morgan Leaf, active in England and in Spain.

So in answering the questions, the date matters. And so does the context. For example, the courts of the kings and great nobility were by definition “trans-national,” and attracted people of all sorts from across Europe. Think of the Limbourg brothers, Dutch by birth, artists who worked for both Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, and Jean, Duke de Berry in the fifteenth century.

Chantilly, Musée Condé, Le très riches heures du duc de Berry, f. 5 verso, May.

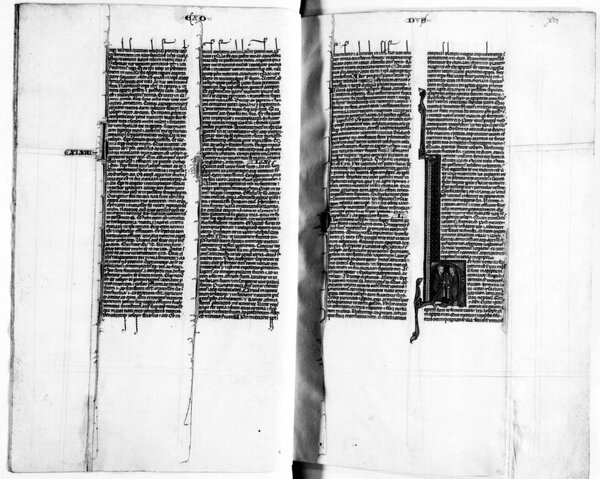

These are all high-end examples of skilled artists working for established monasteries or wealthy lay patrons. Artists travelled; we know that. What about scribes? The medieval universities were by definition international in terms of their students and teachers, and the book trade in the great university cities was international as well. Richard and Mary Rouse have documented fifty-five Britons working in the Parisian book trade and an additional fifty-four people from non-French continental Europe from 1279 to the end of the fifteenth century. These travelling artisans participated in every part of the book trade as scribes, illuminators, bookbinders, and libraires (booksellers and contractors). The same is true in Bologna, home to another important medieval university, although the numbers are very much smaller. Still, there is some evidence that foreign-born scribes worked in Bologna, which brings us to our next example.

Paris, BnF, MS NAL 3189, f. 16 (detail), Bologna, third quarter of the thirteenth century, copied by Raulinus of Fremington in a rounded Gothic bookhand

Raulinus of Fremington copied a Bible, now Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS NAL 3189, in Bologna in the third quarter of the thirteenth century; you can read a detailed description in their catalogue, here, and access a digital facsimile here (made from a black and white microfilm, but still a useful resource). Raulinus was unusually forthcoming, indeed inappropriately chatty, peppering the Bible with sixteen personal notes that include information about his life. Born in England, he describes himself as poor and fatherless, and says he studied arts at the university in Paris, and then ended up in Bologna, where he copied this Bible. (Not our topic today, but I must add that he also complains about his “mistreatment” by two women, Meldina and Vilana; his ribald comments about them are astonishing, especially in this context; read the article by the Rouses cited below and see the BnF catalogue description).

Raulinus thus provides us with concrete evidence of a man, who was born in England, attended the university in Paris, and then worked as scribe in Bologna. From this information, we might expect his script to be a northern Gothic bookhand, of the sort used in Paris. But, remarkably, he copied this Bible in an excellent rounded Gothic bookhand, just the sort of script that was used by Italian scribes working in Bologna. (In contrast, the illumination in Raulinus’s Bible, and perhaps also the pen decoration, all looks rather French, complicating the story of this complicated manuscript even further–again, I refer you to the Rouse’s article).

Les Enluminures, TM 868, Nicholas of Gorran, Sermons, Paris, c. 1275-1300, f. 13. Note the rounded script

Examples of manuscripts from the thirteenth century and later copied in a script that doesn’t “match” the decoration are not that uncommon. Are these evidence of scribes from one part of Europe, working in another? Raulinus’s story proves that a scribe could learn a “foreign” script, a warning to us all. But sometimes, evidence of the script does seem to suggest the scribe was from somewhere else. Our first example, Les Enluminures, TM 868, includes sermons by the Dominican author Nicholas of Gorran (1232-1295). Nicholas was a prominent Dominican preacher and scriptural commentator, who was educated at the famous studium of Saint-Jacques, the Dominican convent in Paris. He became prior of Saint-Jacques in 1280, and then remained there until his death. During his time in Paris, he also served as confessor and advisor to King Philip IV of France (reigned 1285-1314). This manuscript dates from the author’s lifetime, and was almost certainly copied in Paris, given its date, details of the text, and the style of the illumination and penwork initials. The decoration is certainly what we see in other Parisian manuscripts from this time. Details of the script, however–the rounded letter forms, use of line fillers, the fine abbreviation strokes at the very end of descenders–all suggest the possibility that the scribe may have been trained somewhere in Southern Europe, rather than in Paris.

Les Enluminures, BOH 203, Book of Hours, Bruges, c. 1485-1490, ff. 39v-40. Note the rounded southern Gothic bookhand.

The same disconnect between script and painting style can be seen in a very beautiful Book of Hours in our inventory, BOH 203, which was copied in the late fifteenth century and illuminated by artists known working in very characteristically Bruges styles. There is little doubt that this was made in Bruges. Once again though the rounded Gothic bookhand contrasts with the northern style of the painting. This beautiful manuscript is a near-twin to another Book of Hours dated 1486 in the Royal Monastery of El Escorial. Both manuscripts were in Spain by the seventeenth century, and it seems quite likely that they were made in Bruges especially for the Spanish market. There are in fact numerous other examples of Books of Hours made for export from Bruges copied in distinctively “southern” scripts. The question of the nationality of the scribes, however, remains an open one. Were they copied by scribes from Bruges trained to write in a script that would please Spanish customers? Or were Books of Hours like these made by Spanish scribes living and working in Bruges, a final example of scribes moving freely about Europe?

Suggestions for further reading:

Cuenca, Esther Liberman. “Medievalism, Nationalism, and European Studies: New Approaches in Digital Pedagogy”

Geary, Patrick. “European Nationalism and the Medieval Past,” Historically Speaking 3, number 5 (June 2002), pp. 2-4 (available through Project Muse).

Geary, Patrick. The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe, Princeton, N.J, 2002.

Meyvaert, Paul. “‘Rainaldus est malus scriptor francigenus’–Voicing National Antipathy in the Middle Ages,” Speculum 66, no. 4 (1991), pp. 743-763.

Rouse, Richard H. and Mary A. Rouse. “Wandering Scribes and Traveling Artists, Raulinus of Fremington and His Bolognese Bible,” A Distinct Voice. Medieval Studies in Honor of Leonard E. Boyle, Notre Dame, 1997, pp. 32-67 (also included in their collected essays, Bound Fast with Letters).

Rouse, Richard H. and Mary A. Rouse. Manuscripts and their Makers: Commercial Book Producers in Medieval Paris, 1200-1500, Studies in medieval and early Renaissance art history 25, Turnhout, 2000.

Symes, Carol. “The Middle Ages Between Nationalism and Colonialism,” French Historical Studies 34 (2011), pp. 37-46.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!