Recently, it struck me that the sudden move toward a work-from-home culture feels rather like entering into a monastic lifestyle. It’s a perfect time for contemplation, long delayed home-maintenance, and even some handcrafting. If you’re lucky, you’ve been able to spend extra time with your own collection, enjoying the complex content of medieval manuscripts or the drama of framed miniatures. Perhaps, if you don’t have a collection (or even if you do!) you’ve engaged in some traditional crafting practices, from crochet to calligraphy to découpage and collage.

Découpage is an extraordinarily satisfying medium, still very popular now, as it was in the past, especially since the advent of printing. It is a rewarding and rather easy-to-execute technique involving cutting, arranging and pasting paper prints most frequently on objects, such as jewelry boxes, mirrors, cabinets, or tables. Today, you can still enjoy creating découpage objects like coasters with photographs from vintage magazines or re-surfacing old furniture in pet portraits with relative ease. So how and why would this rather crafty medium be used to create a sacred container–– a reliquary–– to house the tongue of the patron saint of Bohemia, St. John Nepomuk?. To answer this question, we should consider the unexpected history of découpage, beginning with its origins in ancient Siberian tombs.

Creating découpage boxes, tables, dressers, and mirrors are a commonly practiced craft today

In Eastern Siberia, felt appliqués were applied to funerary equipment, as some of the first examples of work using a découpage-like technique. Most evidence of this practice comes from the Pazyryka burials–– a group of Iron Age tombs found in the Pazyryk Valley, Siberia, south of the modern city of Novosibirsk, Russia. Barrow-like tombs in this region feature felted collages depicting devotional imagery. More commonly, China is associated with paper cutting and pasting techniques, from paper lanterns to origami to fans. In fact, paper money was invented in China where it was first used as a tender during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE).

An example of the origins of découpage, this is a 5th century BCE felt collage from a burial monument of a chieftain of the Pazyryk culture (sixth to third century BCE in the Altay region). Currently at the Hermitage Museum.

The use of paper spread more slowly in Europe. Paper money was first employed there in the 17th century, although it was not until the invention of steam powered paper mills at the end of the 18th century that paper became the cheaply available resource we are familiar with today. Découpage, as we know it, originated in France in the 17th century as a means of decorating bookcases, cabinets, and other pieces of furniture. The term “découpage” came into use in the 16th and 17th centuries, originating with the Middle French “decouper,” meaning to “cut out of” or “cut from” something.

Creating découpage works with handcolored prints reached its fashionable height in the middle of the 18th century. Marie Antoinette, Madame de Pompadour, Lord Byron, and more recently, Matisse and Picasso all famously created such découpage works.

A reconstruction of Matisse’s studio wall from the Tate Modern’s blockbuster exhibition Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs which explores the artist’s adoption of découpage during his final years. Image via www.scmp.com

Paper reliquaries like our Tongue Reliquary of Saint John Nepomuk may seem unusual as sacred objects, contradictory even, given the humble quality associated with paper today. Yet it is precisely that humility of paper which prompted the sudden and explosive creation of papeyrolles by religious women in convents in the 18th century. According to cultural historian Celeste Olalquiaga reliquaires à paperoles, are usually “glass-covered boxes filled with both human relics and ornaments made with rolled or folded paper,” although they may refer to the paper container on its own. This genre is an offshoot of the entrancing “small paradise” tradition, where glass boxes transformed into a stage for the infant Jesus who was displayed among flora and fauna, creating a diorama that simulated paradise.

On the left: reliquaires à paperoles featuring birds, bouquets, hearts and garlands and reliquaires à paperoles featuring the Agnus Dei. On the right: reliquaires à paperoles featuring Saint John the Evangelist.

Our Octagonal Reliquary Pendant, made out of Fire-gilded brass, glass, velvet, and ink on paper is a composite reliquary similar to the reliquaires à paperoles. This work was likely made in Italy, around 1600

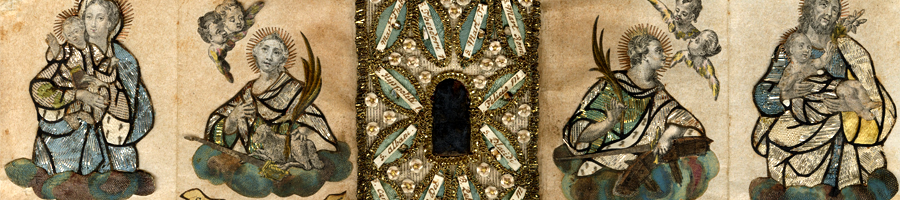

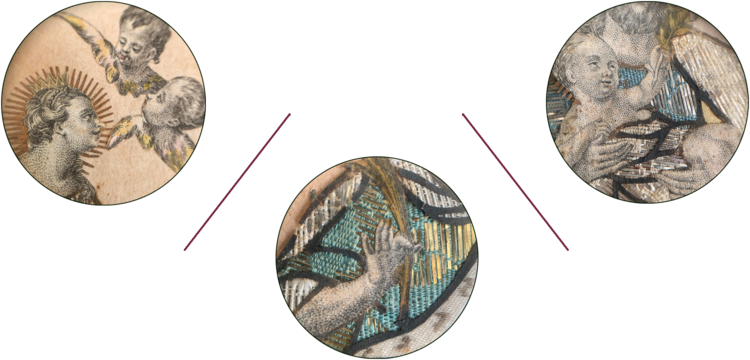

The prints employed in the wings of this cross-shaped reliquary were clearly valued by the nun(s) who created this glittering envelope. Delicately cut, the faces and hands of the prints are preserved pasted to the paper wings and further adorned with collaged and sewn textiles and metal foils as if ‘dressed’ up like paper dolls. In some places the prints have been touched with pigment to simulate ermine-lined robes.

Tongue Reliquary of Saint John Nepomuk with Découpage Paper Wings. Les Enluminures

The centerpiece of this découpage cross is the tongue–– a relic of Saint John of Nepomuk. This rests on a textile base and surrounded with filigree-like metal strips and braided fibers in the form of flower buds or pearls, surrounded by twelve subsidiary relics, all nestled in light blue silk and authenticated with labels

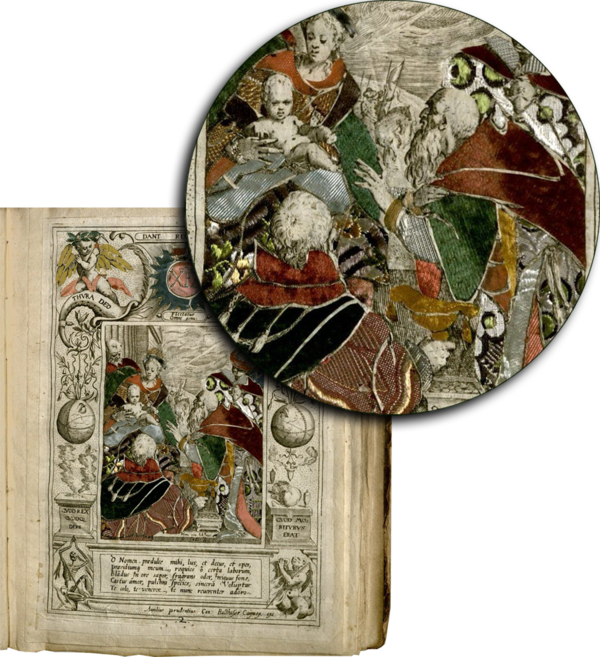

‘Dressed’ prints in the “Salus generis humani” at the Harvard library, created in the 1590s by the engraver Aegidius Sadeler II (1570-1629). They were engraved after the work of the Mannerist painter Johan von Achen (1552-1615) and after drawings of emblematic borders by the draughtsman Joris Hoefnagel (1542-1601). They were “dressed” with textile additions in the 18th century.

Black and mummified, this tongue commands attention, striking a dark contrast to its luscious bed of gold foil and gentle blue silks. Eight figurative vignettes brace the central relics. These découpage wings emphasize the central materiality and presence of the body. They even participate in it through the layering of multiple mediums: collaged textiles interlaced with metal strips that emphasize the labor of weaving, paper, prints, and spiky golden haloes. The flesh tones of the figures are created through a delicate stippling effect that mirrors the grainy surface of the dorsum, where the dotted marks of taste buds can still be discerned.

Tongue Reliquary of Saint John Nepomuk with Découpage Paper Wings, detail. Les Enluminures

Tongues held power in the medieval mind, and beyond. “Sins of the tongue” were commonly documented yet greatly feared. The tongue was able to “break bones” and inflict damage on both the speaker and listeners. This tongue is entrancing, powerful not only as a body-icon but as a representative of the power of language itself.

When folded, the arms of the reliquary embrace these central relics, coating them in a protective layer of sacred names, faces, and hands. Once, this may have been folded closed, sealed with red wax, and lovingly enshrined within a glass case as part of an ensemble creating a reliquaires à paperoles. As a private devotional object, this was made by nuns, perhaps as a gift for the cloisters’ sponsors or even for their own families. It would have functioned as sacred mise en scene, a critical element of elite domestic décor in an elite 18th century household. At first glance this four-lobed object may seem indecipherable, strange even to contemporary viewers. Yet, in it we can recognize our own joy in the transformative magic of craft and collage. It is an important example of the complexity of “nun’s work” and stands as a testament to their playful, yet serious systems signaling the sacred, devised through compounding intricate craft techniques.

Links:

https://www.britannica.com/art/decoupage

https://www.decoupage.org/home/history-of-decoupage

https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/museums/shm/shmpazyryk.html

http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1914560_1914558_1914593,00.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tongue

https://blogs.harvard.edu/houghton/what-the-well-dressed-print-is-wearing/

Citations:

Celeste Olalquiaga, “Holy Rollers,” Cabinet, Issue: 45 (2012).

Martine Veldhuizen, Sins of the Tongue in the Medieval West: Sinful, Unethical, and Criminal Words in Middle Dutch (1300-1550), Brepols Publishers (2017).

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!