For those of you tuning in for the first time, “bibliomorphy” is the study of objects that are recognizable as books (“biblio,” meaning book) because they use the form of the book, but that are created in combination with the forms and functions of other object types (“morph,” meaning to transform). If you have still not read Philippe Cordez and Julia Saviello interesting book on the subject, I highly recommend it: Fifty Objects in Book Form: From Reliquary to Laptop Bag (2020; only available in German).

Philippe Cordez and Julia Saviello, Fifty Objects in Book Form: From Reliquary to Laptop Bag (2020; only available in German). See also Philipppe Cordez on “Feigned Books”

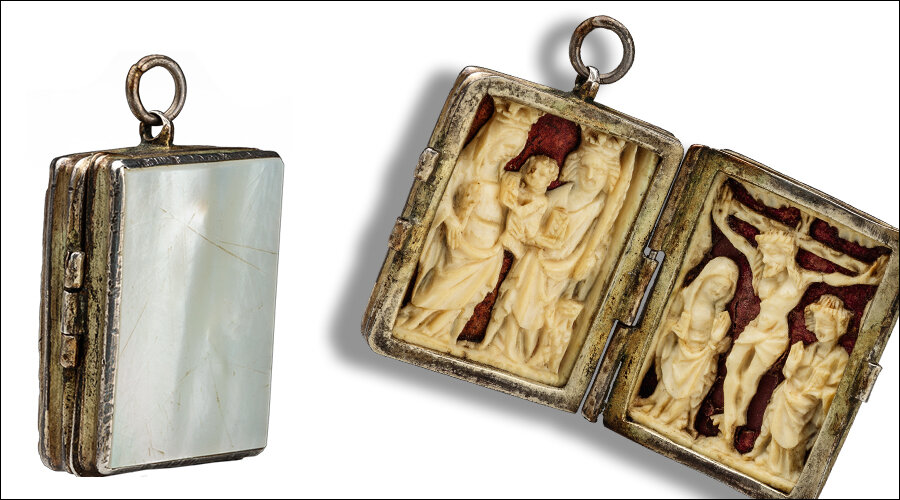

To tantalize readers, my concluding photograph to Part 1, which explored book-shaped jewelry as a category of bibliomorphism, illustrated a Pendant Diptych from the fourteenth century and promised to explore the idea of bibliomorphy back in time, since Cordez and Saviello puzzled over the absence of pre-Gothic bibliomorphs.

In pierced ivory over red-tinted parchment, it depicts the Virgin and Child with a Saint (Margaret?) on the left and the Crucifixion on the right. Hinged rather like a book, the diptych closes to reveal its iridescent mother-of-pearl covers. Just as mother-of-pearl (or nacre) lined the lids of mollusks to protect the pearls birthed within the shells, so it protects the ivory figures within the pendant, themselves symbolic of the cycle from birth to death.

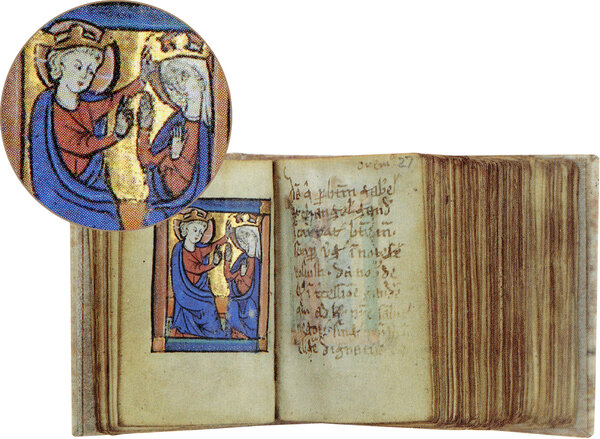

Sometimes the book itself became a jewel, not by combining the book form with another object per se, but by putting it in a pouch to wear around the neck as a pendant. Such was surely the case with the smallest medieval manuscript that has survived, a tiny Gothic Psalter (less than two inches by one inch in size). Is this Psalter only a book; or is it also a jewel by virtue of its function?

Miniature Psalter, France, Lorraine (Metz?), c.1280-1290, formerly Les Enluminures

The Pendant Diptych takes us in another direction, however, one that refines our understanding of the earlier medieval form of the book in combination with other object types. Composed of ivory like the pendant and similarly small (less than three inches by two inches when closed), a set of plaques carved with religious subjects (in this case scenes of the Passion on the outside and scenes of the Infancy on the interior) are joined together like a book.

Booklet with Scenes of the Passion, North French (carving); Upper Rhenish (painting), ca. 1300 (carving); ca. 1310–20 (painting).

©The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is not only the book-like form that relates this work of art to bibliomorphy, but the construction of its interior panels; these have raised edges that would have served to hold melted wax used as a surface for writing with a stylus, perhaps for jotting down short prayers as devotional exercises in response to the subjects of the ivories.

This diminutive ivory example of bibliomorphism reminds us that writing tablets are books too. Writing tablets enjoyed a long history, way before medieval ivory plaques.

Waxed ivory writing tablet, 720BC-710BC, The British Museum

The earliest one that I know of functioned similarly to Gothic tablets and dates from the ancient biblical city of Nimrud part of the Assyrian Empire in the eighth-century B.C. Probably intended for the royal palace of Sargon II at Korsabad, it consists of a folding set of sixteen hinged tablets made out of ivory and scored on the front and back to receive wax to expedite writing with a stylus.

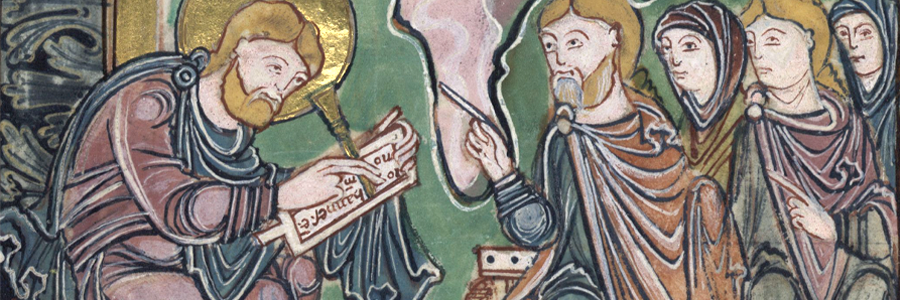

Zachariah writing on a tablet in the Benedictional of Æthelwold, The British Library, Add MS 49598, f. 92v

Eighteen centuries later, when a tenth-century Anglo-Saxon artist wanted to depict an Old Testament prophet Zachariah in the act of writing, the illuminator showed him writing on just such a tablet.

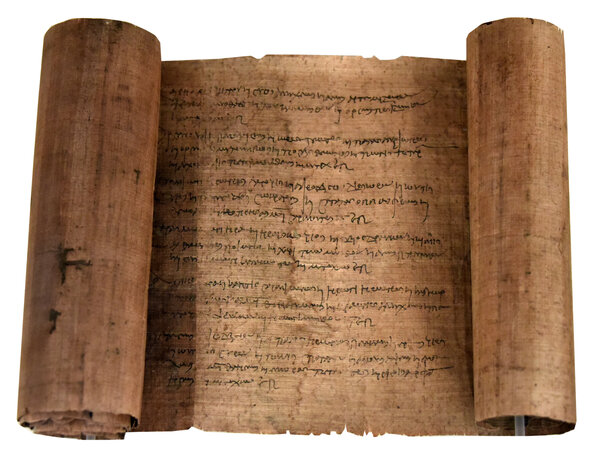

It was the roll, not the codex or the bound book, that was most common form of the book in Antiquity.

Les Enluminures, TM 1135, Documents in Roll Form, England (Ely?), 1541 and 1574

Several factors contributed to the success of the transition from roll to codex. The codex was more easily transportable than the cumbersome roll. Its very structure made it a handier vehicle for reference, facilitating the turning from one page or section of the codex to another. Used for biblical texts, the codex may also have acquired increased legitimacy as it recalled Roman law written in tablet rather than roll form. The very term “caudex” from “block of wood” or “tree trunk” alludes to the wooden frame of Roman writing tablets, rather like a modern-day blackboard.

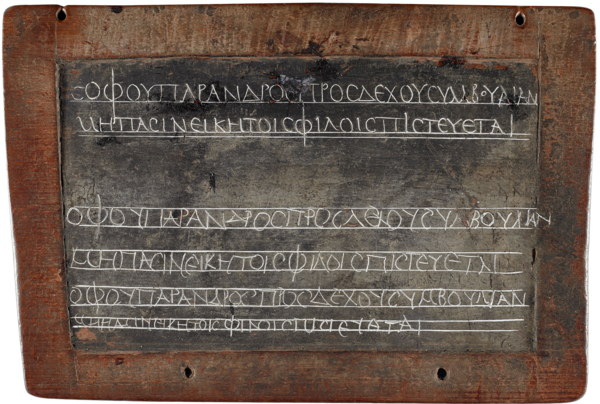

See this example of an ancient exercise school tablet, the first two lines perhaps copied by the teacher followed by the student below.

Tablet 1, The British Library, Add MS 34186

The moment of the transition from roll to codex is beautifully illustrated in this Pompeian fresco from Roman Antiquity.

Roman fresco from Pompeii showing ancient writing materials, Naples, National Archaeological Museum

Fresco showing a woman holding writing implements, a wax tablet and stylus, Naples, National Archaeological Museum

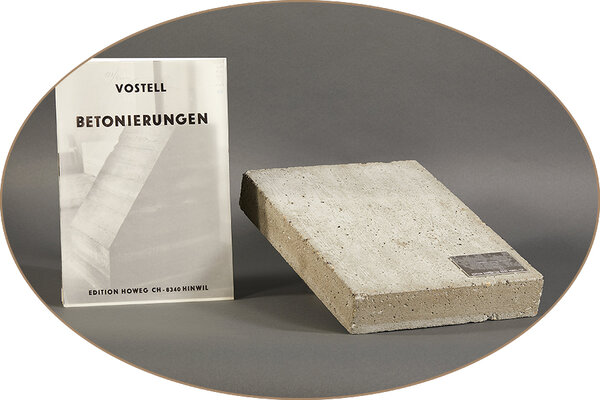

To return to our topic “Bibliomorphy” and Cordez/ Saviello’s publication, we should remember that the Greek word “biblion” embraces rolls, tablets, and bound volume from Antiquity through the Middle Ages to today. To explore further the idea of the book and its many transformations pre-Gothic and post-Gothic, I encourage readers to visit Elizabeth Frengel’s current exhibition at the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center of the University of Chicago: “But is it a Book?” (January 3, 2023 to April 28, 2023). She concludes her online remarks with a intriguing image of an unreadable book by the German artist and one of the founders of the Fluxus movement, Wolf Vostell, called Betonbuch (=Concrete Book), published in Switzerland in 1971. Encased in concrete, is the book really there? How can we know?

Wolf Vostell, Betonbuch, Hinwil, Switzerland: Edition Howeg, 1971, ff N6888.V66 V672 1971 Rare

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!