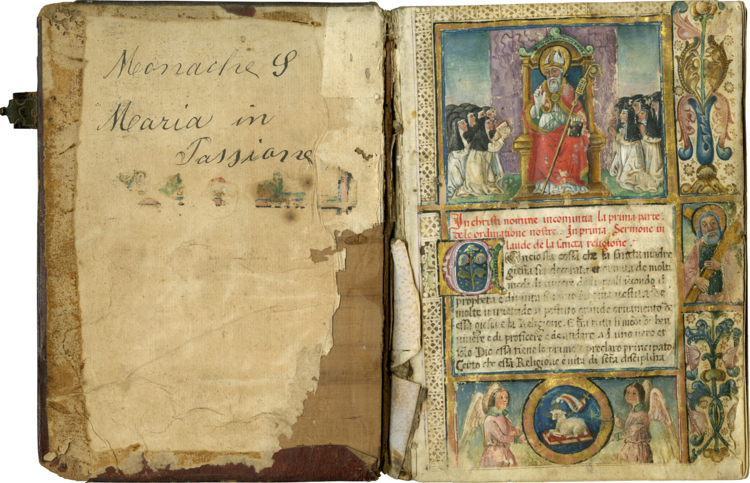

Les Enluminures, Statutes of the Augustinian Canonesses of Santa Andrea della Porta in Genoa, TM 975.

Bibliography Week in NY this year was January 21-25. I’m sure some (many?) of the readers of this blog were in NY that week enjoying the various bookish events; some of you may even remember our previous blog “What’s Up NY” from 2018. We look forward to it every year at Les Enluminures’ New York Gallery. This year, bibliography week featured an amazing exhibition at the Grolier club, “Five Hundred Years of Women’s Work,” which includes selections from Lisa Unger Baskin’s collection at Duke University of more than 11,000 books and thousands of manuscripts, journals, pieces of ephemera, and artifacts.

The exhibition has received rave reviews. Ron Charles of the Washington Post stated, “this is the most remarkable literary show I have ever seen”– high praise indeed, and well-deserved (you can find his complete review here.)

Lisa Unger Baskin is a collector, bibliophile, scholar, and activist; she is now a member of the Grolier Club, although at one time, as she noted in recent remarks, invitations for events at this venerable club of book collectors would arrive at her home addressed to her husband, with the proviso, “Guests, but not including ladies, may be invited.” (Women were not welcomed as members of the club until 1976). She began collecting materials related to women in the 1960s, seeking to recover and recognize the many ways women have supported themselves, their families, and the causes they believed in. “The women’s movement and my compelling interest in these untold stories ultimately led me to focus on unearthing the histories of ordinary women–women who worked every day without recognition or acknowledgment,” said Baskin, who co-curated the exhibit.

Eighteenth-Century Women at Work:

Elizabeth Hare: Musical Instrument Maker […], London: [1741?], Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

Eleanor Ogle, Fruiterer at the Lemon Tree in Covent Garden, London: [ca. 1760], Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

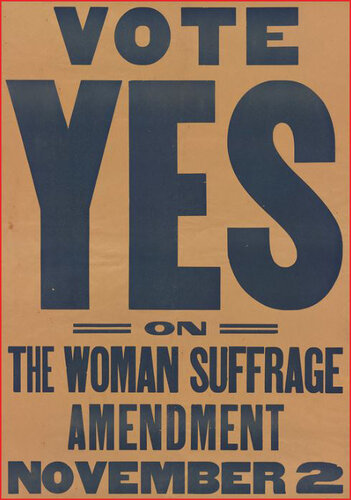

And, in case some of you don’t know, 2020 is also the 100th Anniversary of the nineteenth amendment, something to celebrate -

Vote Yes on the Woman Suffrage Amendment November 2, [New York?]: [Empire State Campaign Committee?], [1915?], Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

What better time to take a look at our current inventory and revisit a topic that we explored in an exhibition and catalogue in 2015, Women and the Book in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. In our current text manuscript inventory, we can point to six manuscripts linked to women; you can find all six described on our site here.

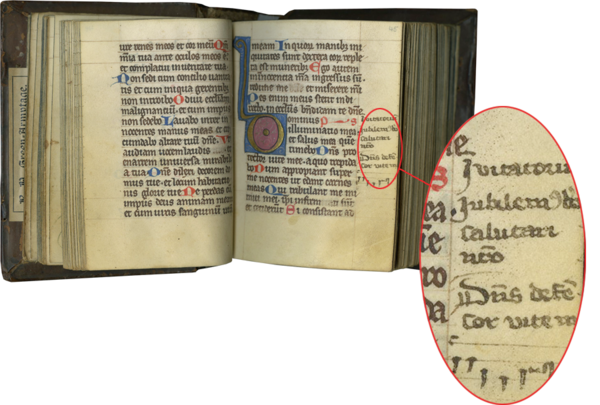

Our earliest manuscript certainly used by women is a charming little Psalter (smaller than your hand, unless you have very tiny hands), made in Germany near Cologne in the later part of the thirteenth century. We know it was copied for use by women, because it includes prayers with feminine forms. It also, and this is interesting, includes prayers in the masculine voice. Nonetheless this almost certainly does not mean that this Psalter was used by men. Nuns copying books for themselves, or others copying books for them, often simply copied the masculine forms in their exemplar without customizing the book for female use. Of course, in theory, one could argue that men sometimes used prayers copied directly out of nuns’s books with feminine forms … but no, I doubt that, don’t you? That just doesn’t seem like something men would do.

TM 1020, Psalter, f. 1. Caption: King David playing his harp at the beginning of a tiny Psalter used by nuns.

We also know from liturgical evidence within the volume that it was made for the use of Premonstratensian Nuns. (The Premonstratensians were founded in 1120 by Norbert of Xanten (c. 1080-1134)). What ho, you might say, I thought there were no Premonstratensian nuns in the thirteenth century!

Eastman/Granada TV series Jeeves and Wooster, screened between 1990 and 1993; Stephen Fry as Jeeves (left) and Hugh Laurie as Bertie Wooster (right).

Decades ago that was the impression one got from historians discussing enactments by the General Chapter of Prémontré that first suppressed the Order’s double monasteries, and then decreed, at some point before 1198, that women were no longer accepted in the Order. See for example Richard Southern’s survey of church history, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages, first published in 1970. Modern historians, including Shelley Amiste Wolbrink, however, have convincingly shown that houses of Premonstratensian nuns were an important presence in Germany throughout the Middle Ages.

A Premonstratensian nun depicted in the Altenberg altarpiece of 1334; Städel Museum, Frankfurt-am-Main, as illustrated in “Clothes Make the Premonstratensian Sister,” by Yvonne Seale.

A small aside, indicative of how our view of history has changed. Southern’s book is one that I have always loved (and still do), but it is a bit dated in some respects; when I went back to it just now to check his statement on this matter, I was surprised to realize that his chapter on women in religion is in the section “Fringe Orders and anti-Orders.” Women are no longer, thank goodness, discussed as “fringe” elements in the history of the Church, although “women’s history,” alas, is yet to be fully integrated into many historical discussions.

Image of Mary sheltering Premonstratensian Canons and Nuns; see “Norbertine Sisters in the World.”

Could our manuscript have been used in a “double monastery” that included both Canons and nuns (explaining the male and female forms of the prayers)? Double monasteries were certainly part of the early history of the Premonstratensian Order, and the effectiveness of the decree abolishing double monasteries within the Order in c. 1138-1141 is far from clear. However, at least in the examples studied by Wolbrink in Northwestern Germany, in many cases foundations described as “double monasteries” by modern historians were in reality houses of nuns, with the presence of men restricted to a priest and a few male conversi to provide spiritual support and manual labor.

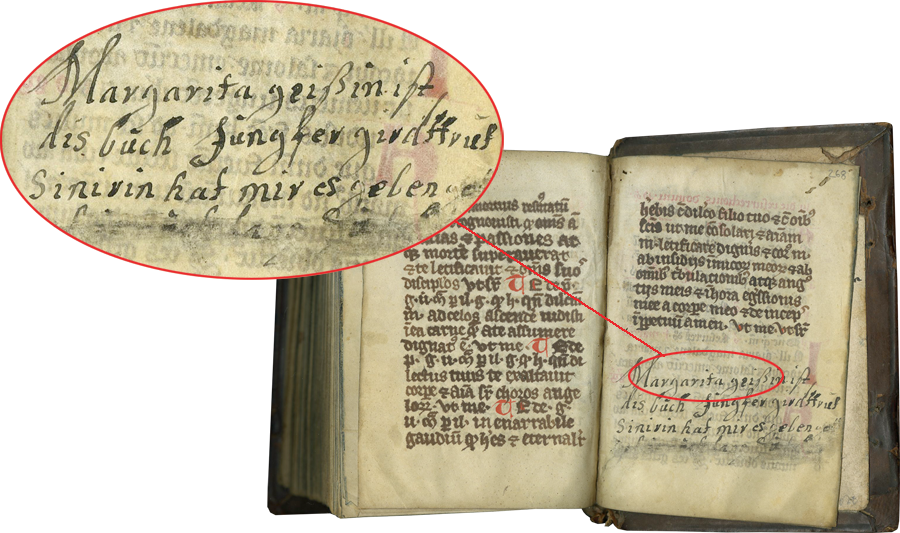

Premonstratensian Psalter, TM 1020, f. 268, ownership note added by Margarita Geissin in the seventeenth century.

By the seventeenth century the manuscript was owned by two German women, who left their names in the book, suggesting continued devotional use by women, but in this case by lay women.

Prayers and musical notation for the Divine Office added in the margins of a Premonstratensian Psalter, TM 1020, f. 45.

Our Psalter was certainly used by the nuns during the Divine Office, the daily liturgical prayer celebrated by nuns, monks, and other religious, including the secular clergy. Prayers and music for the Office were added in the margins throughout the volume. Many surviving manuscripts known to have been owned and used by women surviving from the Middle Ages and later are liturgical volumes.

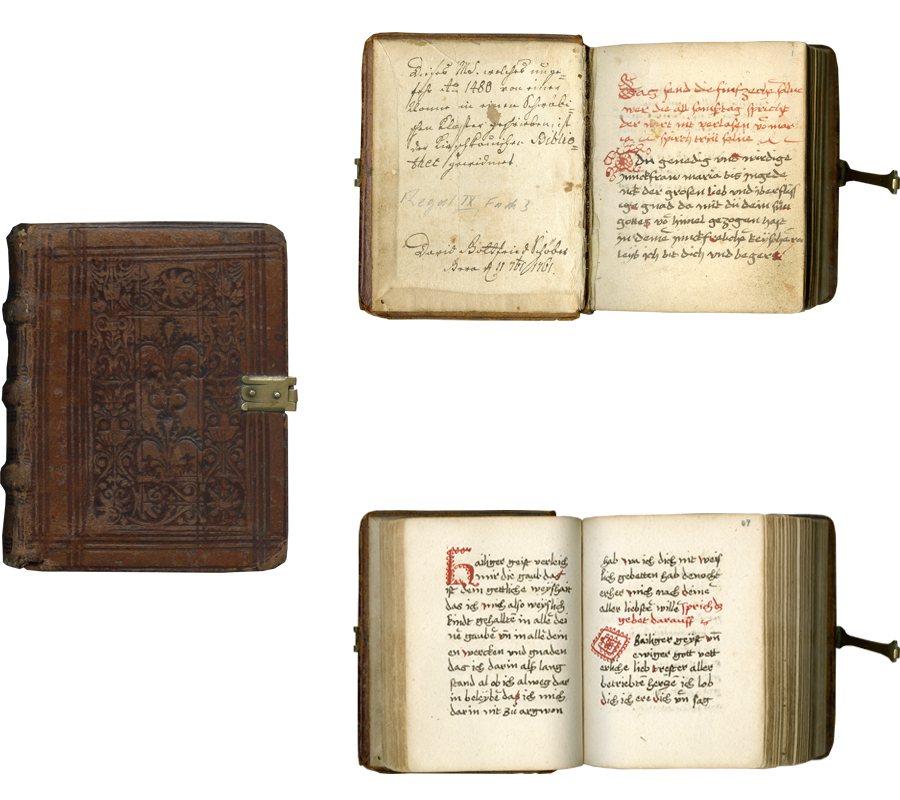

German prayer book copied by nuns for their own use, TM 893, f.1 and ff.46v-47

This very tiny, intimate manuscript, notably in German rather than in Latin, however, was made for private prayer, rather than for the formal corporate prayer of the liturgy. It was made for the use of nuns (once again, there are prayers using the female voice), and almost certainly copied by the nuns themselves, in a convent in the region around Ulm and Augsburg in the second quarter of the sixteenth century. It is a very personal book, with devotions designed to accompany its owner throughout her daily life.

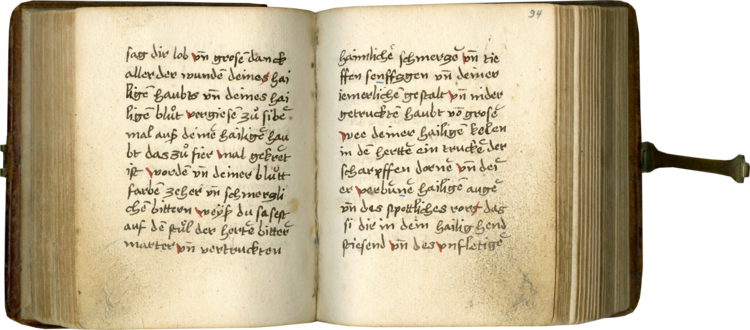

Dirt in the lower margins of this prayer book reveals which prayers in the volume were the nuns’s favorites; TM 893, ff. 93v-94.

Attention to dirt and other signs of use in manuscripts has been brought to our attention in the work of the eminent historian of medieval manuscripts, Kathryn Rudy (we’ve talked about dirt and other signs of use before in this blog, see “Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder.” Some of the prayers in this volume, including the first eight prayers, petitions to Mary to aid at the hour of one’s death, and an extended meditation on the Christ’s suffering and the crown of thorns, show signs of particularly intensive use (dirt in the outer corners, and handling to the point where the parchment is almost translucent).

Manuscript detailing the daily life of the nuns at Santa Andrea della Porta in Genoa, TM 975, f. 1.

One final example takes us to Genoa, and a remarkable volume copied in 1511 at the monastery of Santa Andrea della Porta by Father Gregorio da Piacenza, confessor of the nuns (he thoughtfully included a colophon at the end of the volume telling us all that). Originally a monastery (one of the oldest in Genoa) for Benedictine nuns, in 1510 Augustinian Canonesses Regular of the Lateran congregation replaced the earlier Benedictine congregation. This manuscript, with its wonderful illuminated frontispiece that includes a picture of the nuns, marked this important moment in the history of the convent.

The volume is a customary or statute book for the convent, detailing the new rules that governed the daily life of the nuns. It is fascinating reading. Its first thirty-three chapters discuss the liturgical life of the convent, but much more. To name just a few examples, topics discussed include how the nuns should speak through the grate at the door and behave with men entering the convent, that the nun who distributes the mail must show discretion with regard to the content, obedience, manual work, meals, blessings and readings in the refectory, the election of the abbess, and clothes and shoes. The second part of the text explains how the nuns who fail in their duties will be separated from the others. Punishments include eating bread and water on the ground, kissing the feet of the other nuns, washing dishes, remaining silent, and being imprisoned for a year.

If you are interested in manuscripts related to women and the book, please visit our site and read about our other three books related to women: a liturgical volume with texts in Latin and German, including medical, culinary and cosmetic recipes (TM 947);

TM 947, Noted Breviary for select feasts; short Mass texts in German; recipes (medicinal and cosmetic), f.1 and f.33v.

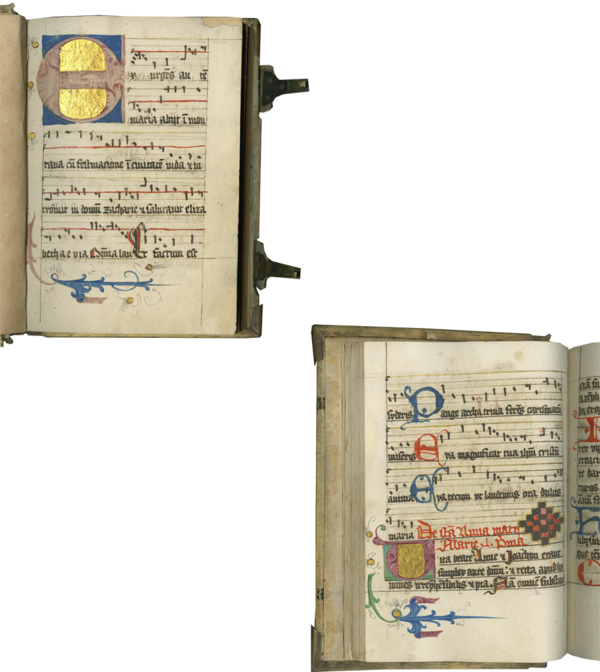

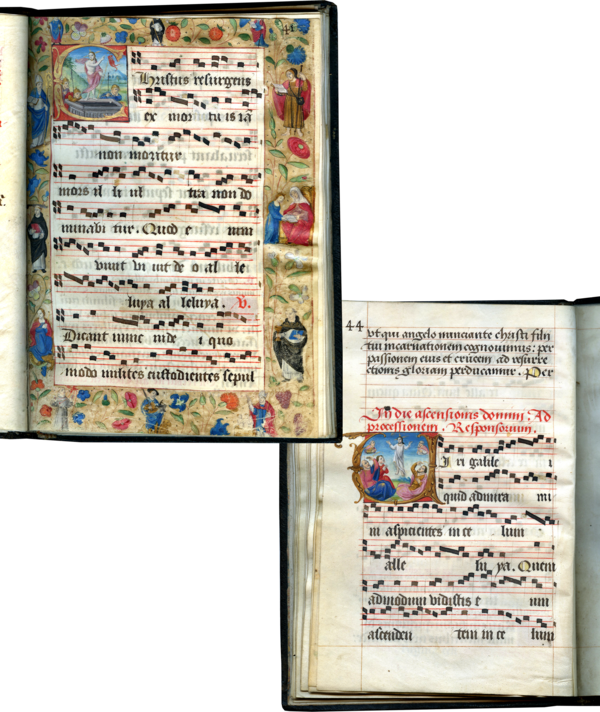

an illuminated Processional made for, and customized by, Dominicans nuns in Rouen (TM 1031);

TM 1031, Processional (Dominican use), p.41, the Resurrection and p.44 the Transfiguration.

and finally, an exquisite illuminated copy of Jerome’s Letter to Furia (TM 935) on being a widow, in a unique French translation (we’ve talked about that book before in this blog, “Modern Love”, but since then in a recent publication Dr. Katja Airaksinen-Monier has suggested this volume may have been made for Louise of Savoy (1476-1531), regent of France and mother of King Francis I and Marguerite of Navarre).

TM 935, JEROME, Letter LIV To Furia (To Furia, On the Duty of Remaining a Widow), in the translation by CHARLES BONIN. ff.4v-5

At the moment I am writing this, there are 77 manuscripts on our text manuscripts site; the number of books we can link to women–six–is not a very large percentage of the total. What can we make of that? Certainly, it is true that throughout the Middle Ages, books made, owned, and used by men were much more common than those for women. Or so we always say. But I wonder, how influenced are we by gender-bias? When describing a medieval or Renaissance manuscript, I assume it was made for (or used or owned by) a man, or a male community, by default, unless there is evidence that explicitly contradicts this. How many of these books were actually for women? Literary historians studying texts from this period are beginning to ask how many literary works long assumed to have been written by men, were actually by women, and it is time that book historians follow suit.

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!