Perhaps if you studied the history of art (from Pyramids to Picasso, we used to call it colloquially) in school, you are familiar with pictures representing surgical operations such as Rembrandt’s masterpiece, the Anatomy Lesson Dr. Tulp, or that by the American realist Thomas Eakins, The Gross Clinic. The former illustrates the dissection led by Dr. Nicolas Tulp of the forearm of a corpse to show the musculature of the human body, but it’s most noted for its transformation of the group portrait in the Golden Age of Dutch painting. The latter depicts a famous surgeon, Dr. Samuel Gross, lecturing to a group of five physicians on the operation of the left thigh. It is lauded for its grasp of nineteenth-century scientific realism and has even been called “one of the greatest American paintings ever made.”

On the left: "The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp" by Rembrandt. On the right: "The Gross Clinic" by Thomas Eakins.

Attending the same hypothetical course, you probably never saw this tenth-century Byzantine manuscript with an illumination of the “first” surgical separation of conjoined twins

Skylitzes, Ioannes, Synopsis of Histories, Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, MS Vitr. 26-2, fol. 131r.

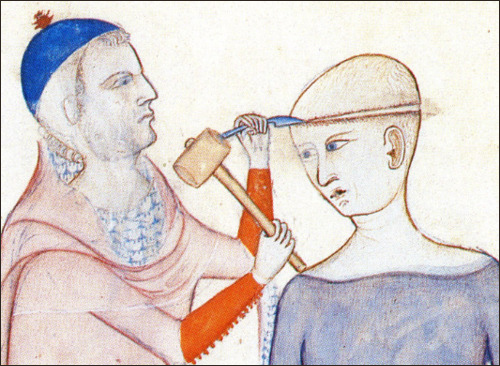

or this one of a medieval surgical procedure for curing headaches (trephination) in a fourteenth-century Italian volume

Unknown artist, Surgeon Conducting a Trephination in Guy of Pavia’s Anatomia, c. 1345, tempera colors on parchment.

Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly, Chantilly (Ms. 334).

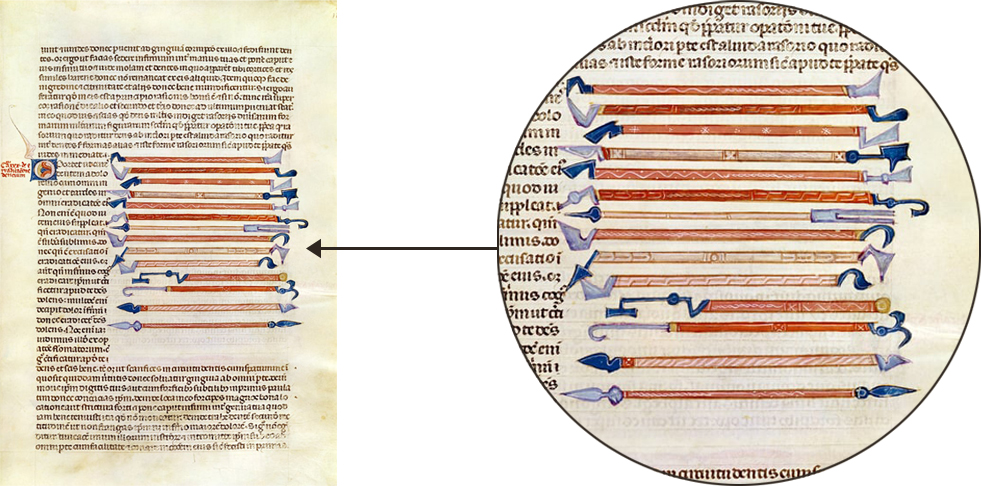

or this one depicting the surgical instruments at the disposal of a thirteenth-century physician.

Ms 89 Ter fol.115 Surgical instruments from a treatise by Abul Qasim Kalaf ibn al-Abbas al Zahrawi (Albucasis).

I am not making a case for changing the way we teach art history here – or for inclusion – but rather simply want to suggest how rare, yet how interesting, medieval medical manuscripts can be even to the general public. We all want to know what ails us and how to cure it. We all have either been or known someone who has been under the surgeon’s knife, so to speak.

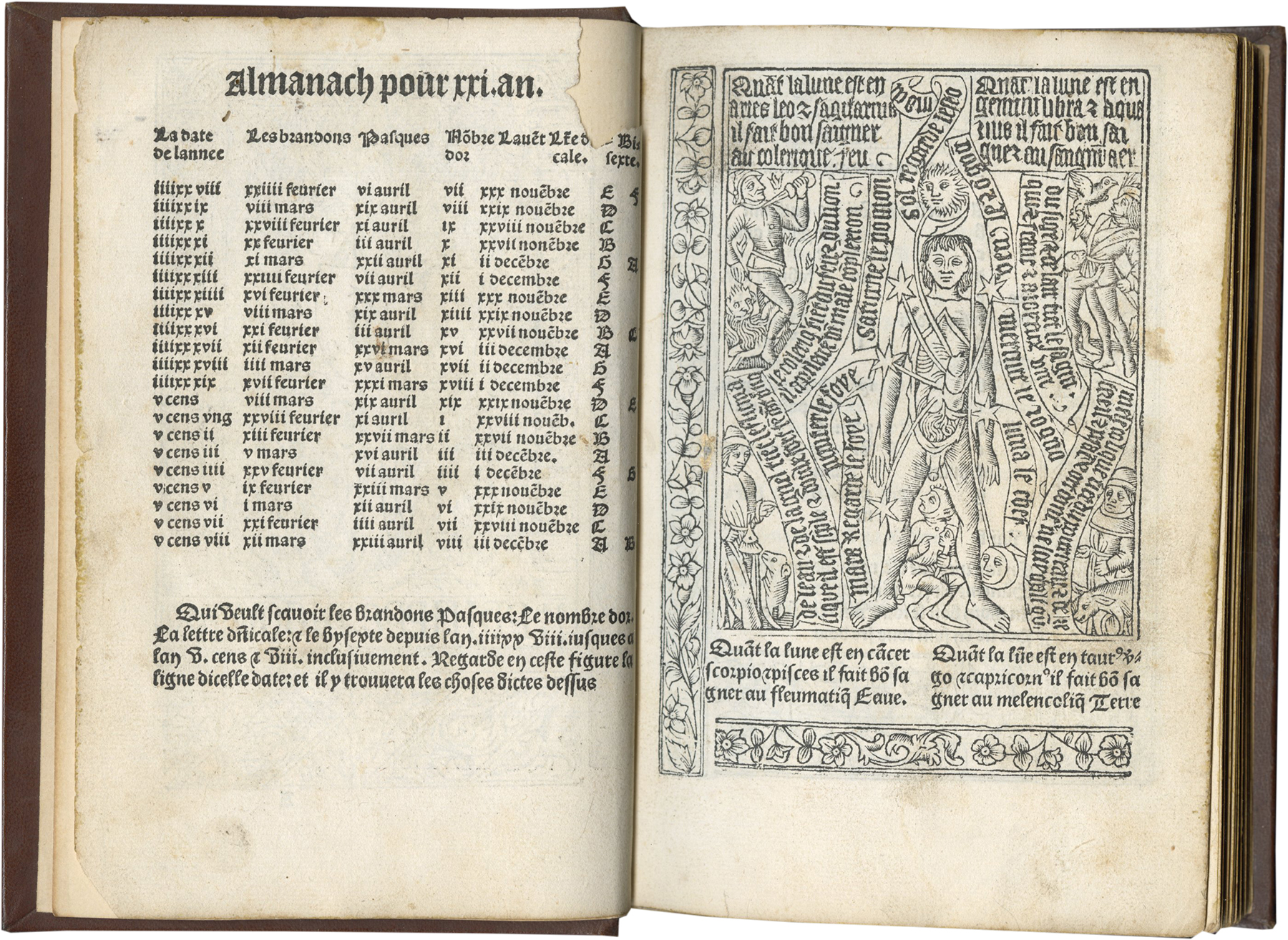

But are illustrated medical manuscripts from the Middle Ages rare? Not as rare as you might think. In a 1965 checklist of medical illustrations in medieval manuscripts, Loren MacKinney found more than 800 (approximately 825) manuscripts worldwide with one or more illustrations of medicine. More than half a century later the number is surely higher and may top one thousand. Not all of these are manuscripts of surgery. Many are herbals, or astrological miscellanies with the ubiquitous Zodiac Man, and some are veterinarian handbooks. Only a few are actually illustrated surgical manuscripts, and virtually all of those are in the public domain.

Les Enluminures, BOH 228, Printed Book of Hours (Use of Lyon), France (Paris), Philippe Pigouchet for Toussaint de Montjay, July 30, 1495 (dated colophon), sig. A2, [Zodiac and bloodletting practices].

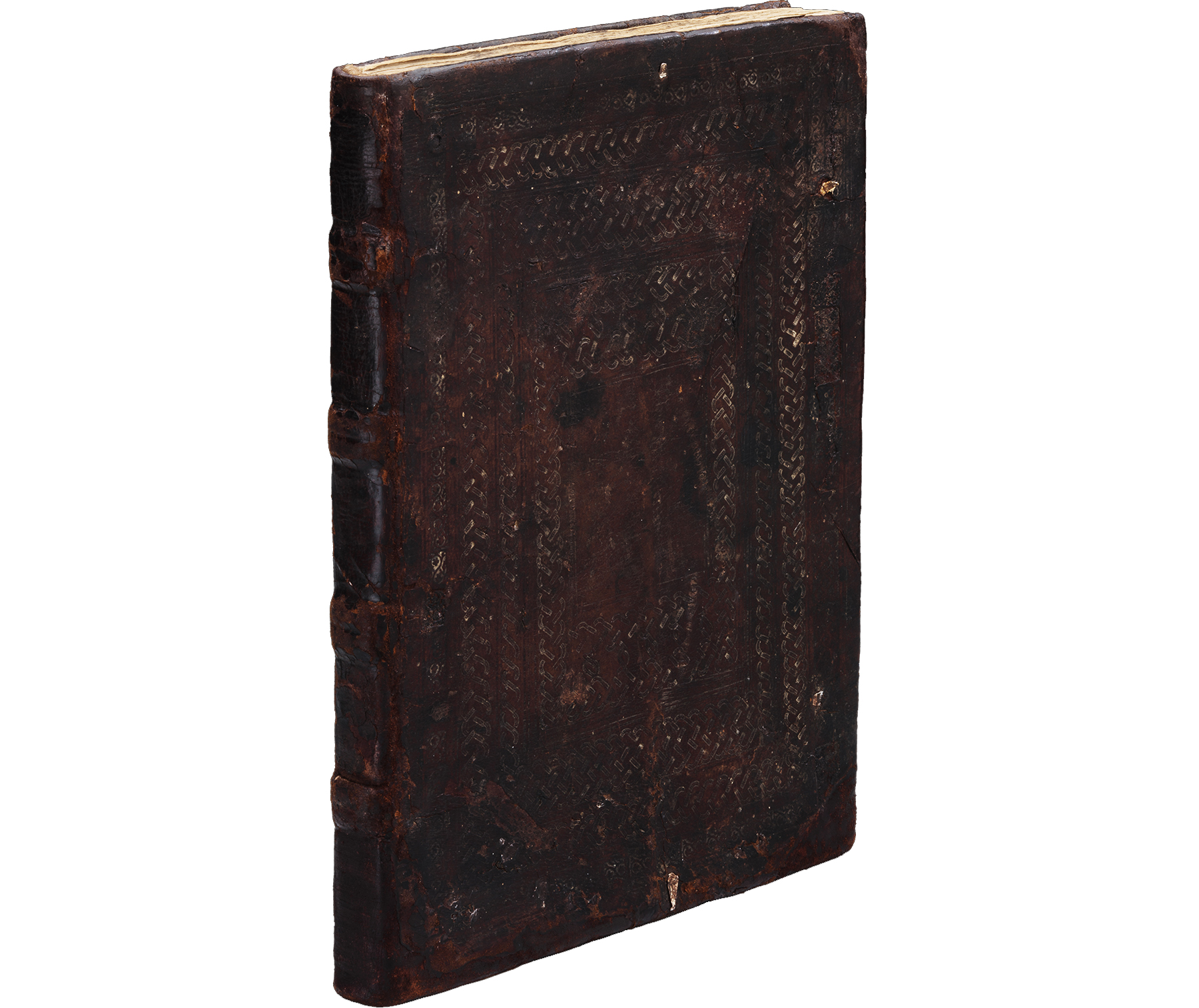

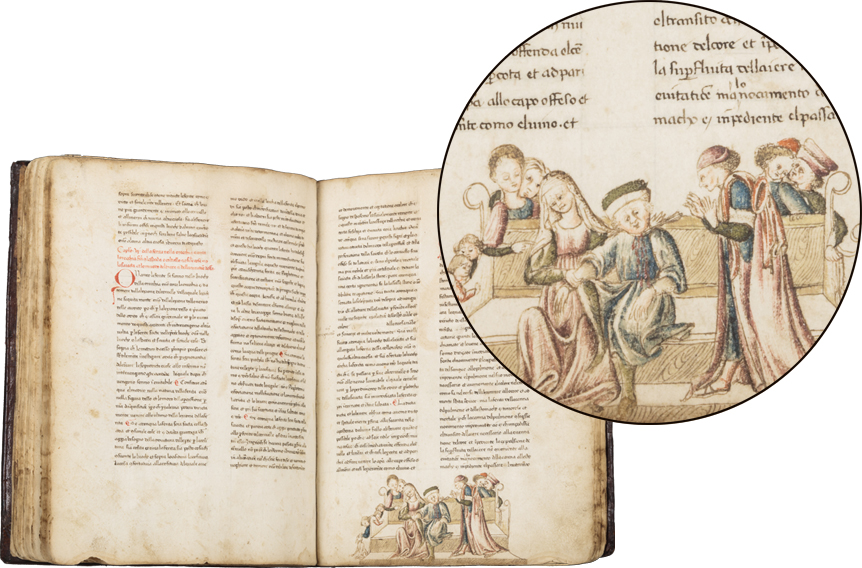

Rare then indeed is this fifteenth-century illustrated manuscript of the Surgery of William of Saliceto (c. 1210-1280), a thirteenth-century physician whose work set the standards for the “when,” “what,” and “how” of medieval surgery for centuries to come.

William both taught and practiced surgery in northern Italy, and his style of medicine became known as a “rational” discipline. Made almost two centuries after William lived, the present manuscript demonstrates the survival of William’s ideas and procedures in medical communities in Italy. It was owned and used by a practicing surgeon in Umbria, and it even preserves its original sturdy tooled leather binding.

Written in readable Italian, whereas William wrote in Latin, it is one of only two surviving manuscripts of this Italian translation. Five watercolor illustrations in the manuscript focus on some of William’s innovative procedures.

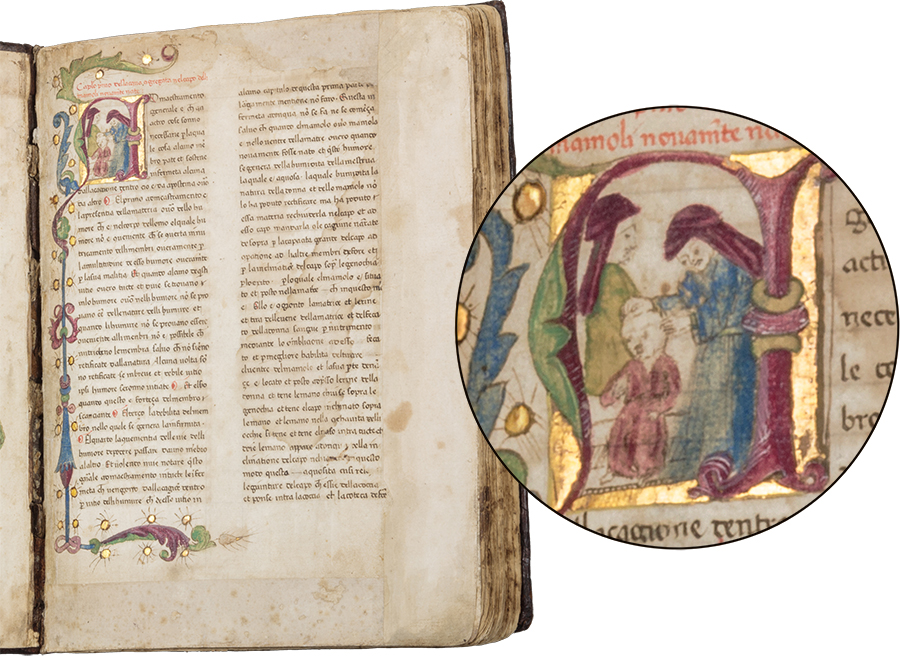

William’s manual of surgery in Book I proceeds from head to toe, and the manuscript opens with an image that appears in no other manuscript of William’s Surgery: the procedure for curing hydrocephaly in children.

Les Enluminures, William of Saliceto, Chirurgia (Surgery), Central Italy, Umbria (Perugia?), c. 1440- before 1457, f.1, historiated initial ‘A’ with two physicians examining the head of a hydrocephalic child.

As the surgeon anoints and heats the child’s head, he also punctures the scalp at the forehead to provoke the release of fluids, a practice that is not unlike the modern-day use by today’s surgeons of a shunt to cause drainage for the same condition. On the front pastedown facing the opening miniature William himself is portrayed directing a physician who removes a fistula from the upper arm of a patient.

Les Enluminures, William of Saliceto, Chirurgia (Surgery), Central Italy, Umbria (Perugia?), c. 1440- before 1457, pastedown, full-page author portrait of William of Saliceto wearing a red chaperon and seated in a high-backed wooden chair

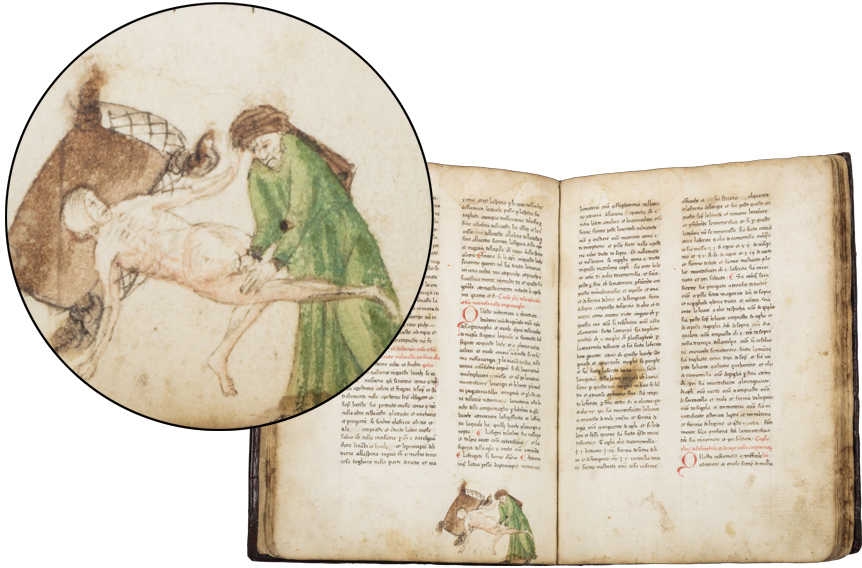

In chapter 27, he describes how he cured a “difficult to diagnose” deep abscess in the upper arm of a German man. Moving down the human body, the next two illustrations focus on the groin. In the first the physician operates on a hernia in the groin (chapter 44) by incising and then pressing on the protruding lower abdominal area,

Les Enluminures, William of Saliceto, Chirurgia (Surgery), Central Italy, Umbria (Perugia?), c. 1440- before 1457, f. 18v, lower right margin, a physician examining the groin of a nude patient lying on a pillow;

and in the second the physician examines the penis with a long instrument (chapter 48). Many of the operations on the sexual organs deal are designed to treat venereal disease.

Les Enluminures, William of Saliceto, Chirurgia (Surgery), Central Italy, Umbria (Perugia?), c. 1440- before 1457, f. 22, lower right margin, a physician treats an infected penis with a cautery iron, with both figures on a gray ground (illustration to Book I, chapter 48).

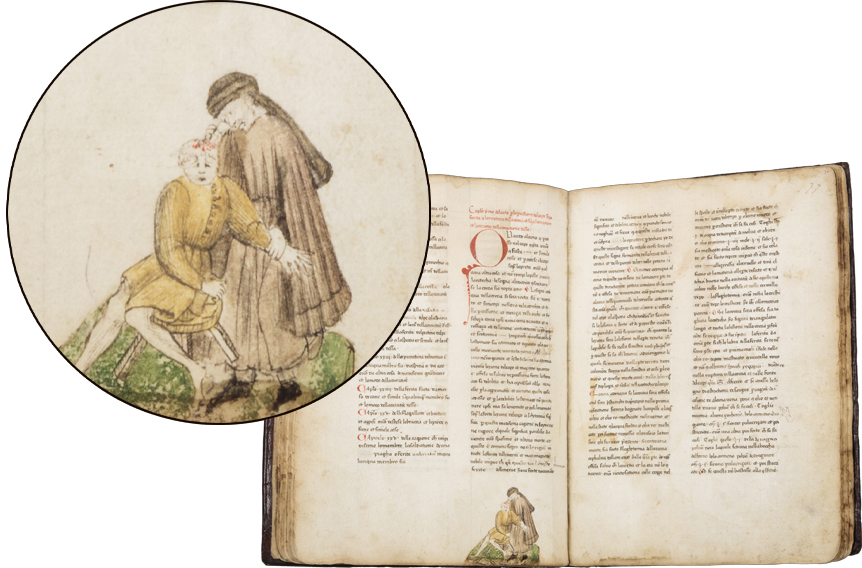

Following the same order as Book I, that is, moving from head to toe, Book II treats wounds and contusions, beginning with the diagnosis of a concussion in chapter 1: “When someone receives a blow on his head from a weapon or a fall on a rock, and the skin is not rent, the surgeon must determine if the skull is fractured.” William goes on to cite many of the same symptoms we look for today: vomiting, giddiness, floating spots in the eyes, unconsciousness, etc. Much to his credit, he is one of the first surgeons who presumed the presence of nerves that led from the brain to other areas of the body like the stomach and thus were responsible for some of these symptoms.

Les Enluminures, William of Saliceto, Chirurgia (Surgery), Central Italy, Umbria (Perugia?), c. 1440- before 1457, f. 31v, lower right margin, a physician operating on a fractured skull, the patient seated on a stool, both figures on a green ground (illustration to Book II, chapter 1).

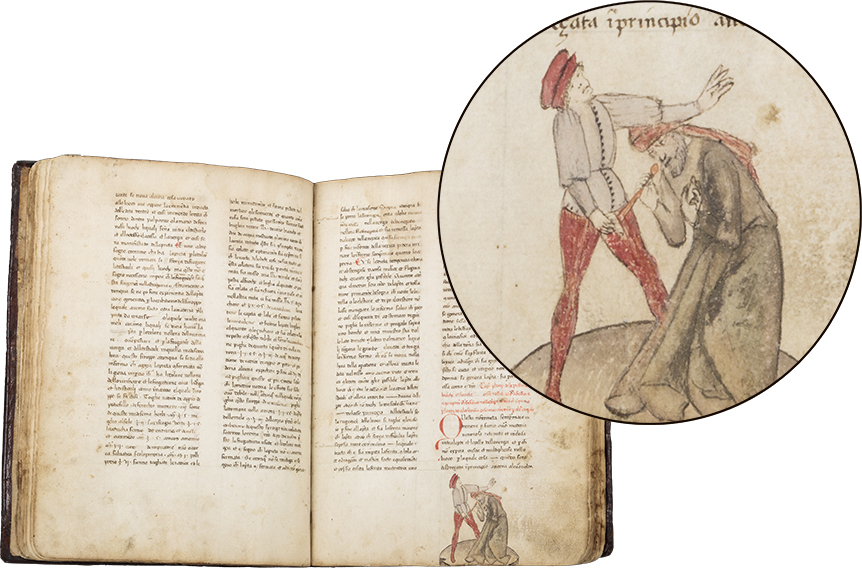

A final illustration to Book II shows the dismayed reaction of a physician and the gathered audience to the predicament of a young man with an arrow stuck in his throat: “all wounds to the throat are serious because they might damage the windpipe or the esophagus ….” Although sometimes William found it was possible to suture the wound and halt the bleeding, all too often the physician’s dismay was justified because the patient “died in my presence within the hour.”

Les Enluminures, William of Saliceto, Chirurgia (Surgery), Central Italy, Umbria (Perugia?), c. 1440- before 1457, f. 42, lower margin, a physician approaching a man and woman seated on a wide wooden bench surrounded by a crowd, and a patient with an arrow in his neck.

This manuscript illustrates only a fraction of William’s Surgery, although it is the most extensively illustrated of all the extant volumes of the text. But I read the entire text in an accessible, recently reprinted English translation (see Rosenman, The Surgery of William of Saliceto 1898, repr. 1998).

As a woman, I was struck by his serious discussion of breast cancer (chapter 34), recommending a mastectomy unless the cancer is too advanced and has spread to the veins (lymph nodes). We often think of the Middle Ages as full of magic and trickery, hokey pokey, and malarky; medieval almanacs tell us when we can engage in bloodletting, start a journey or stay home, plant crops, conceive, harvest, and so forth, based on the positions of the moon and planets. In fact, one Farmer’s Almanac I consulted informed me that today, January 14, was the day for making jams and jellies. Instead I am writing a blog. But the voice in William’s surgery is that of an alternative Middle Ages. Plainly worded and serious-minded, William’s introductory remarks could be put in the mouth of any modern-day surgeon: “surgery is a science that teaches the principles behind the procedures for manual operations on the soft tissue, nerves, and bones.” A recent article on the revived aesthetic of medieval design, in part popularized by Tik Tok, called it “Middle Ages Modern” (acronym MAM), which could also describe the writings of William Saliceto, a MAM man who emerges from the past to remind us that yesteryear was not so entirely different after all.

Sandra Hindman

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!