I collect works by Dora Maar. She was the mistress of Picasso from 1936 to 1945.

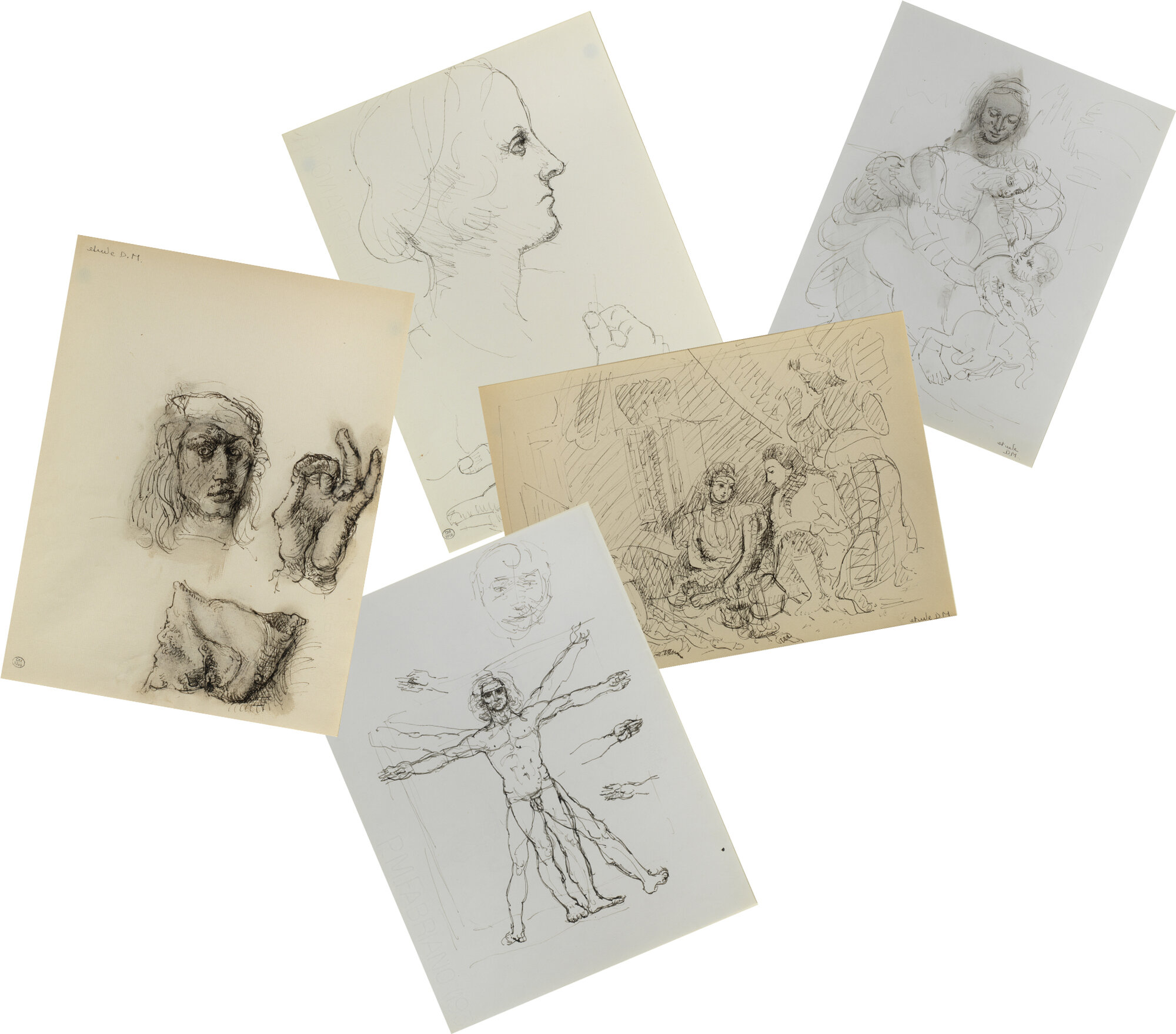

Before meeting Picasso, she was a surrealist photographer of considerable renown, but Picasso disdained photography as “not art,” and so in his formidable presence she turned to draftsmanship (her “dessins d’après les maîtres”) and eventually to painting.

At this point you are wondering: What does this have to do with Joel ben Simeon? I will tell you.

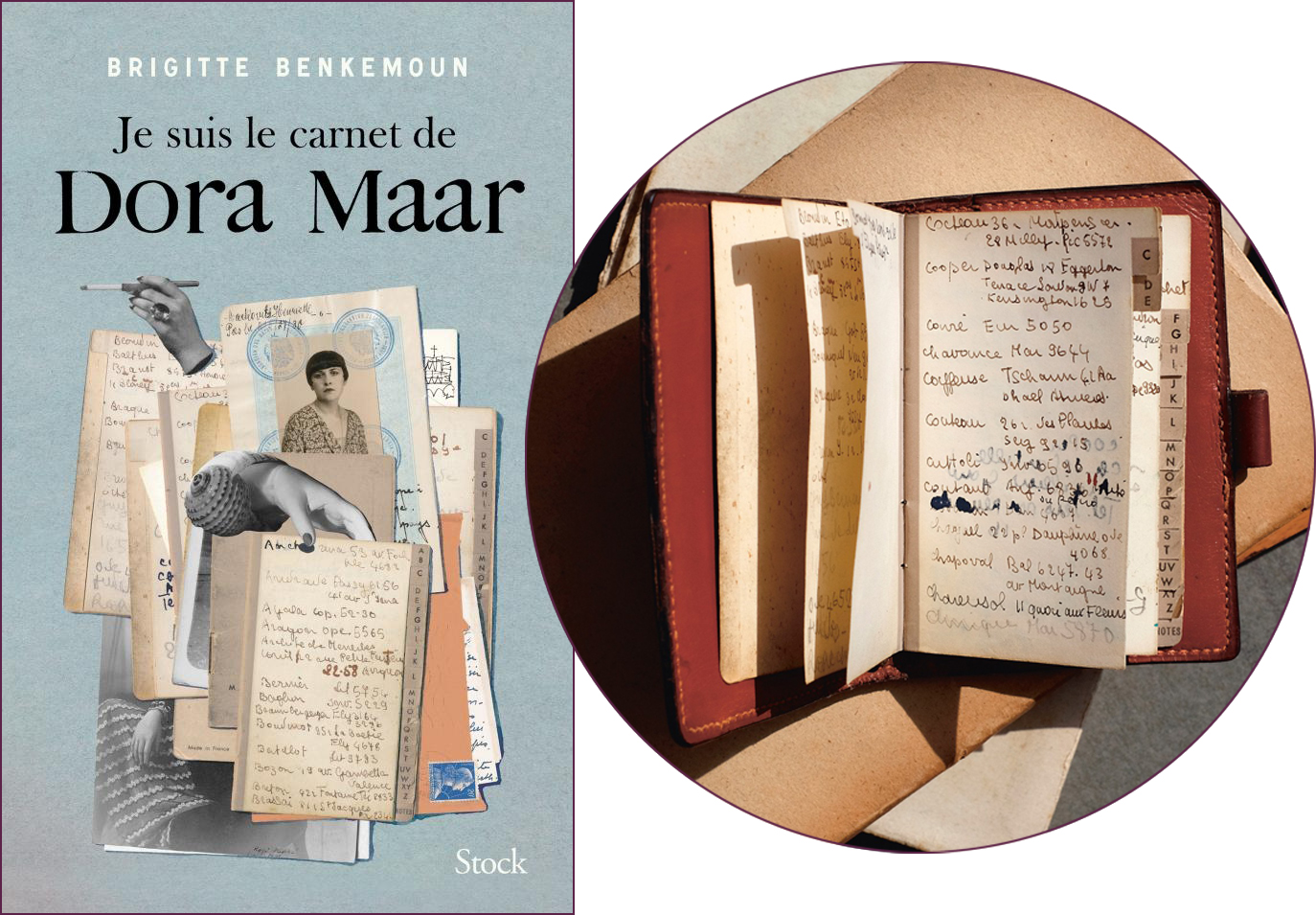

In 2019, a French journalist-writer-television director Brigitte Benkemoun, seeking to replace her husband’s vintage Hermès address book, purchased one on eBay. It arrived. It bore no name of the owner. But it was filled with names and phone numbers: Breton, Brassaï, Braque, Balthus, Cocteau, Éluard. It presented a mystery. To whom did it belong? By teasing out the names, their interrelationships, even their phone numbers and addresses, Ms. Benkemoun discovered she possessed Dora Maar’s address book from 1951. The book she subsequently wrote – Je suis le carnet de Dora Maar – unraveled Dora Maar’s life from the entries included in the Hermès address book

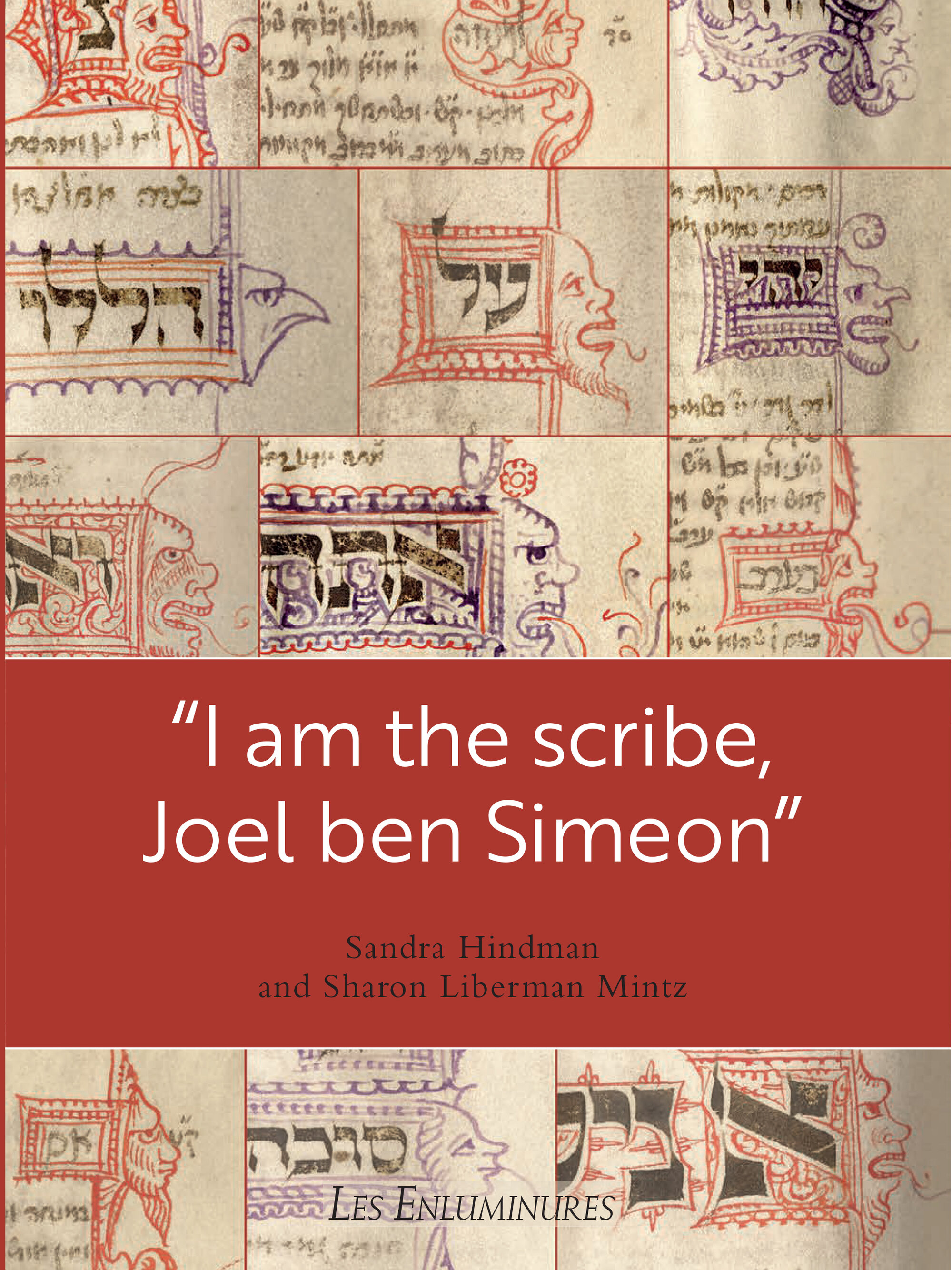

I was enchanted by Benkemoun’s publication and the story behind it. Since then, I have wanted to write a book about someone from the Middle Ages – author, scribe, illuminator, patron – where I could tell their story from one or several primary sources. Newly published, “I am the scribe,” about Joel ben Simeon is my Je suis le carnet de Dora Maar.

“I am the scribe, Joel ben Simeon”, text by Sandra Hundman and Sharon Liberman Mintz with an essay by Lucia Raspe. Les Enluminures, 2020.

Although we do not have Joel ben Simeon’s address book, we have a remarkable amount of information in his “voice” starting with his many elaborate colophons and extending to his often highly individualized drawings linking word and image.

So who is Joel ben Simeon? Active from the 1440s to about 1490, he is one of the most famous, perhaps the most famous, figures in late medieval Hebrew manuscript production. Born in Germany, he spent a large part of his career in northern Italy as an itinerant craftsman, as we learn from the dozen manuscripts he signed “I am the scribe,” often adding the place of production and the name of the patron.

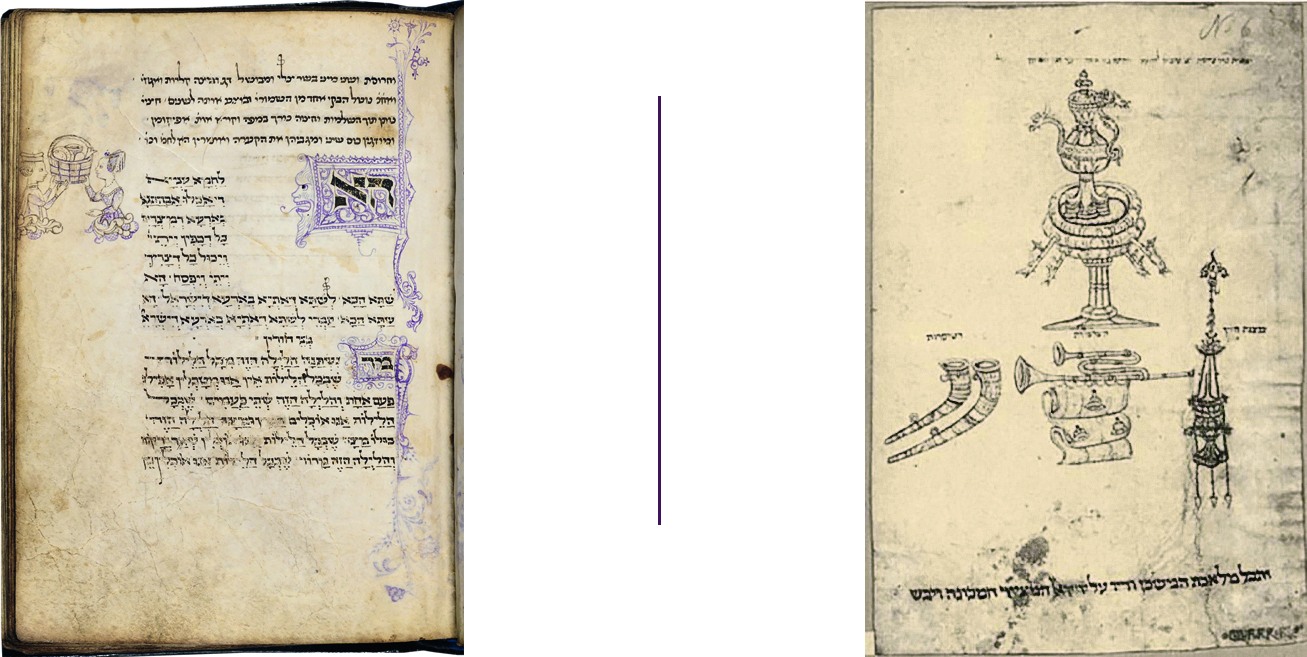

On the left: Maraviglia Tefillah, f.39r, Young Woman and Man raising the Seder Basket, London, British Library, Add. MS 26957. On the right: six leaves with Depictions relating to the Tabernacle, Italy c. 1460's, location unknown, formerly MS 0822, Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary, New York.

He tells us he was also the illustrator in many of these signed manuscripts, and today, in addition to the twelve signed manuscripts, there are twenty-two attributed manuscripts for a total of thirty-four manuscripts. Given the low survival rate of Hebrew manuscripts compared to their Christian counterparts, the sheer output this total number reflects is truly remarkable.

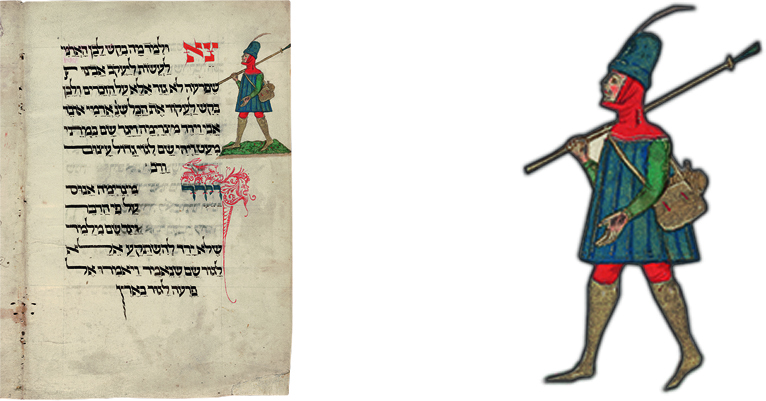

The present manuscript, previously unrecorded in the extensive literature on Joel ben Simeon, combines a book of prayers (Siddur) with a book of customs (Sefer Minhagim) and was written in 1449/1450. I like to think of the Siddur as the Hebrew equivalent in Jewish homes of the Book of Hours, that is, a manuscript containing prayers recited at home at different times a day (thrice daily in the Siddur and eight times a day in the Book of Hours).

On the left: the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, ff. 1v–2, MS M.917/945, The Morgan Library & Museum. On the right: Oppenheimer Siddur, f.20v, MS. Oppenheim 776 Bodleian Library.

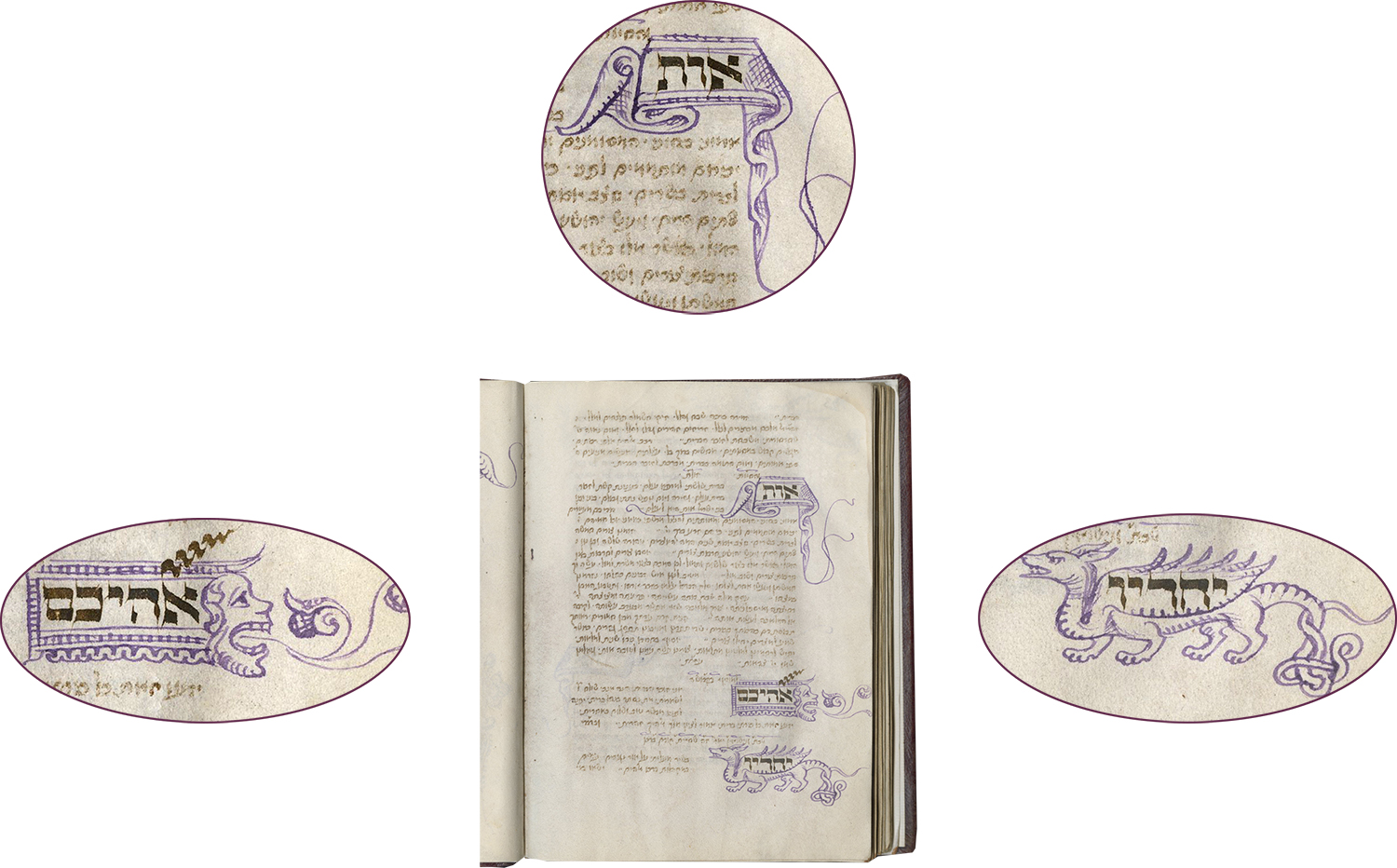

In the case of this manuscript, there are more than 500 pen and ink drawings Joel added around 1470. It was produced in northern Italy, perhaps in Treviso, and certainly in the Veneto, hence the name we assign it: the Veneto Siddur-Sefer Minhagim.

Les Enluminures, the Veneto Siddur and Sefer Minhagim of Joel ben Simeon (Ashkenazic rite, use of Ulm), in Hebrew, manuscript on parchment, in 2 volumes of 121 leaves, with approximately 500 pen and ink drawings, Northeastern Italy (Treviso?), dated 1449-50, decoration added c. 1470.

I have studied and taught medieval manuscripts, including Hebrew manuscripts, nearly all my adult life. I fervently believe that a complete history of European illuminated manuscripts should incorporate those by Jewish scribes and illuminators side-by-side Christian ones. But I never studied Hebrew, a deficiency that has proven to be an insurmountable obstacle to primary research. Hence, my collaboration in “I am the scribe” with the eminent scholar, Sharon Liberman Mintz, to whom I am greatly indebted. With the help of Sharon, my desire is that Joel ben Simeon's story will reach not only a niche market of Hebrew manuscript collectors, but a wider audience interested in the complexities of production of all manuscripts in the late medieval period and in the very impulses that drive creativity.

The “impulses that drive creativity,” that is the key phrase here. For, in metaphorically looking over Joel ben Simeon’s shoulder, I felt I could capture the very moment of his artistic process in a way that is hardly ever possible with medieval manuscripts.

Les Enluminures, the Veneto Siddur and Sefer Minhagim of Joel ben Simeon (Ashkenazic rite, use of Ulm), in Hebrew, manuscript on parchment, in 2 volumes of 121 leaves, with approximately 500 pen and ink drawings, Northeastern Italy (Treviso?), dated 1449-50, decoration added c. 1470.

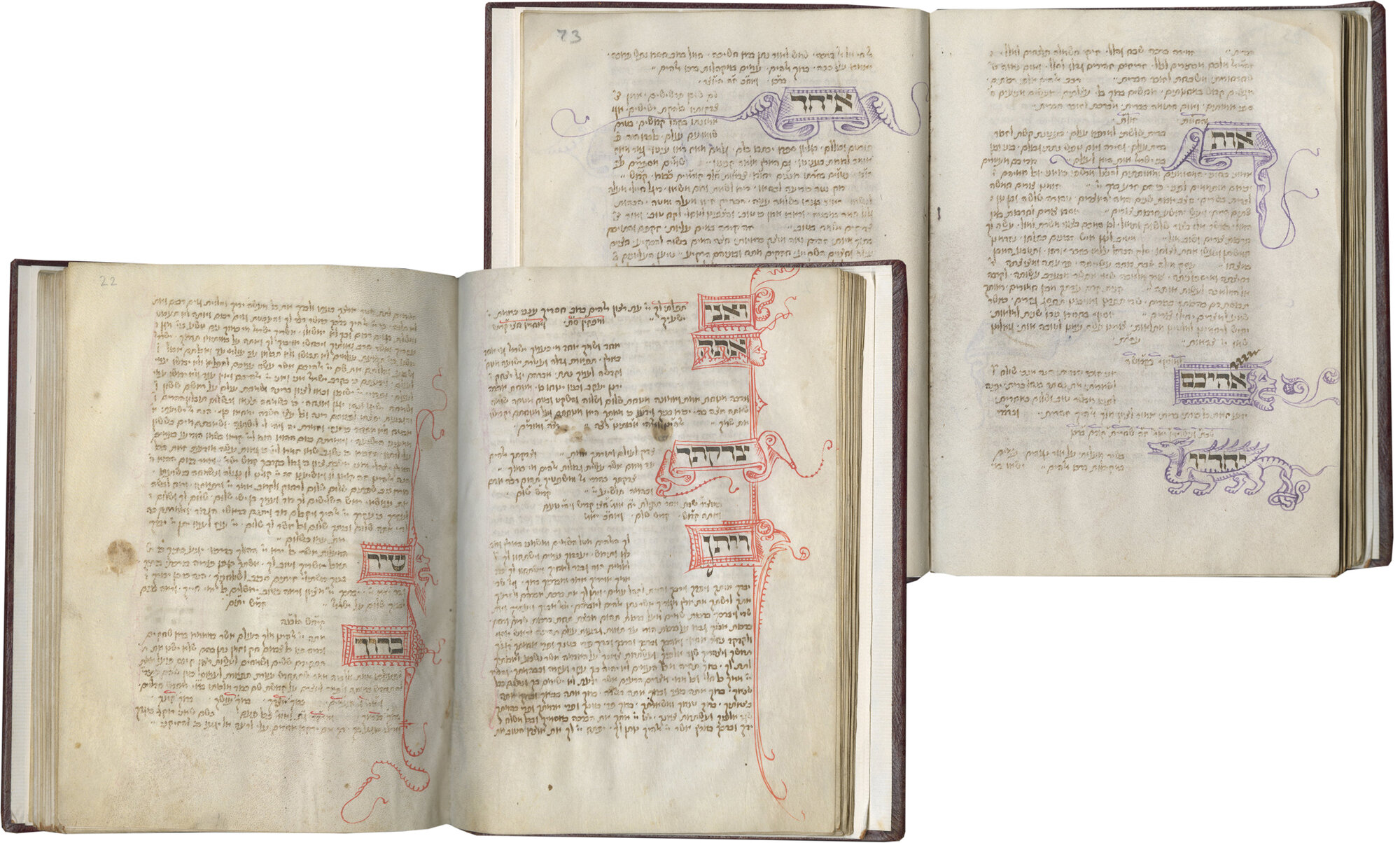

The form of art he favored, free-hand drawing, is more spontaneous than finished manuscript illumination, which is laboriously built up in layers on the parchment as the pigments are laid down one by one after the careful application of gold leaf. Remembering that Joel was an immigrant and an itinerant Jew without access to an established workshop, we might speculate that drawing was a more accessible medium for him since it was less costly and did not require the outlay of funds necessary for precious mineral pigments and gold leaf. In any event, Joel responded with aplomb to the text, often in highly creative ways.

On the left: details from the Veneto Siddur-Sefer Minhagim, Les Enluminures. On The right: Joel ben Simeon, Panel of Heads (Guests at the Seder), Bodmer Haggadag, f.4v, Cologny Geneva, Bibliotheca Bodmeriana-Foundation Martin Bodmer, Cod. Bodmer 81

One of my favorite motifs of his in the Veneto Siddur-Sefer Minhagem is the mask, of which we find close to one hundred drawings—mostly profile heads of men and women talking, singing, laughing, frowning, grimacing, being silent. These masks resemble innovative frontispieces in Haggadah manuscripts he illustrated in which a framed grid of faces accompanies the invitation to all Jews to gather round the table at the Seder: “this is the bread of our affliction that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt.”

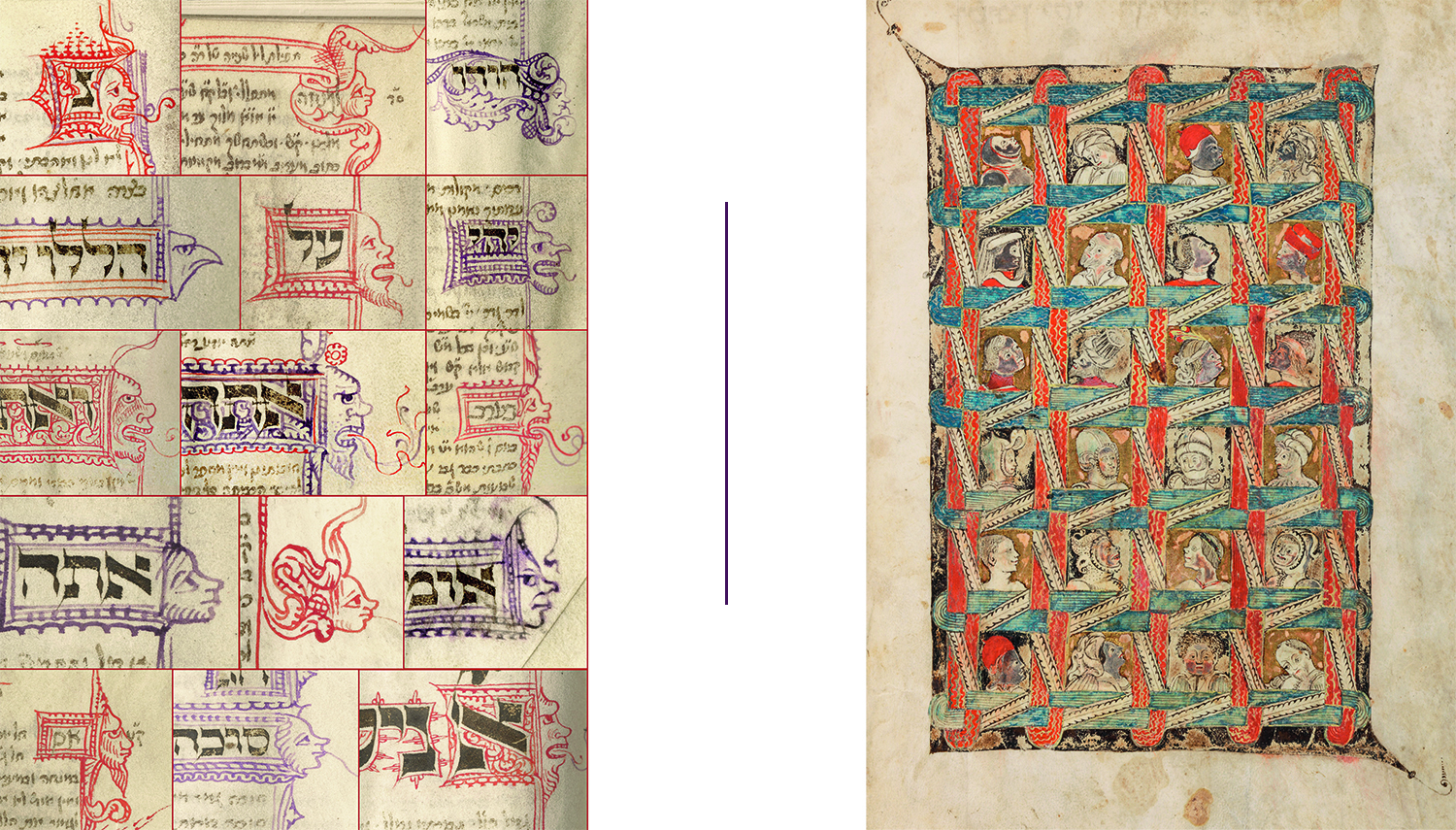

Joel found a visually unique way to celebrate his status as an itinerant artist and immigrant Jew. In at least six of his manuscripts, he illustrates a text of the Haggadah “Go forth and learn” with a figure of a man in travel costume with a lance, a bag, and a water container.

Washington Haggadah, f. 34v, Colophon, Germany, 1478, Washington D.C., library of Congress, MS Heb. 1.

This part of the Haggadah narrates how Jacob “went down to Egypt and sojourned there.” So, this image represents Jacob. But it is also a self-portrait of Joel, who not only traveled from town to town in Italy, but returned to his German homeland at least twice, crossing the alps at a time when such a journey even in the summertime must have been very arduous. He used the image of “the traveler Joel-Jacob” so often that it has been called a “kind of trademark.”

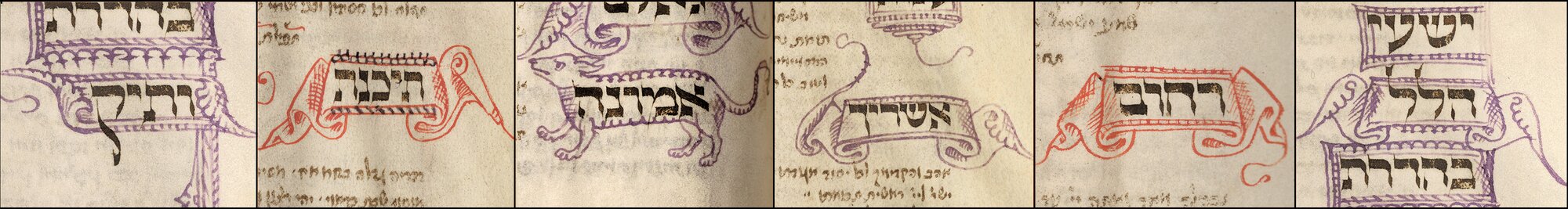

The personality that emerges from his manuscripts is that of someone who is curious about people, learned and literate, and highly inventive. I was particularly taken by the speech bubbles or banderoles he uses in our manuscript. They occur with almost infinite variety on page after page as frames for the initial word panels (a special feature of Hebrew manuscripts comparable to historiated initials in Latin manuscripts).

There are nearly fifty of them, all different, in the Veneto codex. Although not uncommon in Gothic manuscript illustration, both their frequency and originality in this manuscript by Joel are striking. It is as though Joel (“I am the scribe”) knew he was “speaking” to his readers through his imaginative banderoles.

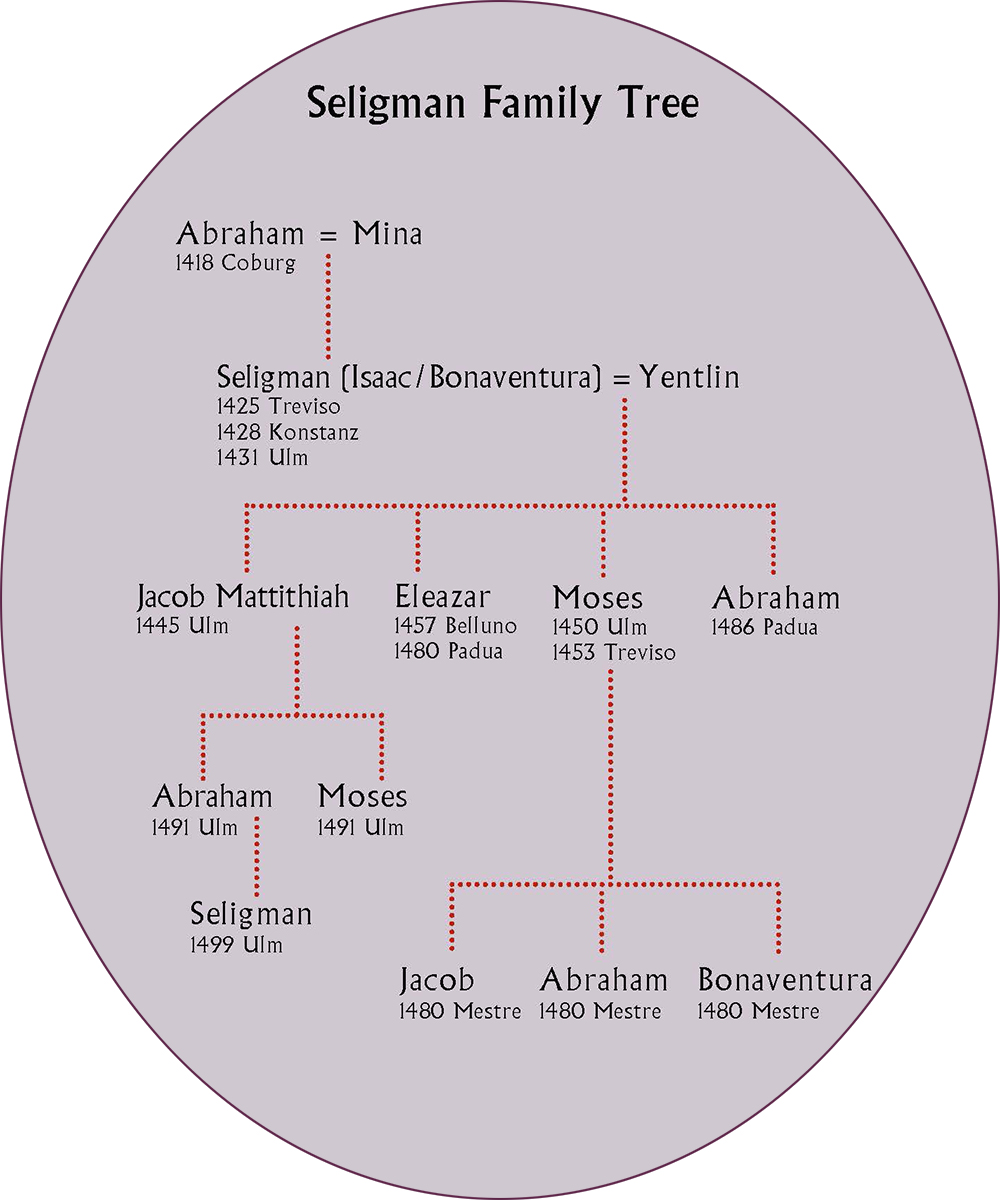

Just as I can imagine Joel’s creative process as a artist-scribe in the Veneto Siddur-Sefer Minhagim, so too its circumstances of production are revelatory. We know from signed manuscripts that Joel worked for a wealthy banking family, the Seligman’s, who like him had a foot both in Germany and in northern Italy.

The father, Isaac, had four sons, of which the eldest Jacob remained in Germany where he took over the lucrative family banking business in Ulm, while the three others moved to Italy, bankers all of them. Three out of four brothers were bibliophiles, and they certainly had the money to satisfy their tastes. Early in his career Joel worked for Jacob in Germany, who probably sang his praises to his brothers, something like this: “Look I know this Jewish artist who now lives near you in Italy. Why don’t you contact him to illustrate your manuscript?” So, indeed, Joel did some work for brother Moses living in Treviso, thus becoming a kind of “house artist-scribe” for the Seligman family. Truly it was a small world in these northern Italian towns. Fewer than 150 Jews lived in Treviso in 1425 and less than one hundred in other centers such as Mestre, Padua, and Pavia. These close relationships among Ashkenazic Jews in the Italian hinterland come alive in our manuscript.

Joel joins the small pantheon of people I have worked on who will now always be part of my life. When I say I metaphorically looked over his shoulder what I really feel is that I was there. He’s my friend now. He’s in good company with Christine de Pizan, Chretien de Troyes, and Marie de France. Making new friends this way is one of the best parts of being a scholar.

Order the publication: “I am the scribe, Joel ben Simeon”

You can now receive periodic blog post updates by submitting your email up above in “Follow Us.” Make sure to follow us also on Instagram (@lesenluminures), Facebook (Les Enluminures) and at our Twitter (@LesEnluminures)!